History of Hydro-Québec facts for kids

Hydro-Québec is a big company in Quebec, Canada. It's owned by the government of Quebec. Since 1944, Hydro-Québec has been in charge of making, moving, and delivering electricity to homes and businesses all over Quebec. Its main office is in Montreal.

How Hydro-Québec Started

After the Great Depression, many people in Quebec wanted the government to take over the electricity business. They thought electricity prices were too high and companies were making too much money. Politicians like Philippe Hamel and Télesphore-Damien Bouchard looked at how Ontario had taken control of its electricity in 1906. They wanted Quebec to do something similar.

When Adélard Godbout became Premier of Quebec in 1939, he liked the idea of a government-owned electricity company. He was upset that two main companies, Montreal Light, Heat & Power (MLH&P) and Shawinigan Water & Power Company, controlled everything. He felt they were inefficient and working together in a bad way. He even called them an "economic dictatorship."

1944: The First Step to Government Control

In 1943, the Godbout government proposed a new law. This law would allow the government to take control of MLH&P. This company provided gas and electricity in and around Montreal, Quebec's biggest city.

On April 14, 1944, the Quebec Legislative Assembly passed this law. It created a new public company called the Quebec Hydroelectric Commission, or Hydro-Québec. The new law gave Hydro-Québec the only right to distribute electricity and gas in the Montreal area. It also said Hydro-Québec should serve customers "at the lowest rates" and improve the electricity system. It also aimed to bring electricity to rural areas that didn't have it.

Hydro-Québec took over MLH&P the very next day. The new leaders quickly realized they needed to make much more electricity to meet the growing demand. By 1948, Hydro-Québec started making the Beauharnois power station bigger. Then, they looked at the Bersimis River near Forestville, far east of Montreal. The Bersimis-1 and Bersimis-2 power stations were built between 1953 and 1959. These projects were a big test for the new company. They also showed what future large projects in Northern Quebec would be like.

Other projects built during this time included another upgrade to Beauharnois and the Carillon generating station on the Ottawa River. Between 1944 and 1962, Hydro-Québec's ability to produce electricity grew six times larger!

1963: The Second Step to Government Control

The 1960s brought a period of big changes in Quebec, known as the Quiet Revolution. This time also brought new energy to Hydro-Québec. A young and energetic minister, René Lévesque, was put in charge of Hydraulic Resources. He was a former TV reporter and a popular figure in the new government.

Lévesque quickly approved the ongoing construction of dams. He also put together a team to take over the 11 private companies that still controlled a lot of Quebec's electricity.

On February 12, 1962, Lévesque started telling the public why this was important. He said the private electricity business was an "unbelievably costly mess." He traveled around Quebec to explain his plan and calm people's worries. He also argued against the Shawinigan Water & Power Company, which was the main company against the takeover.

Finally, on September 4 and 5, 1962, Lévesque convinced his government colleagues to go ahead with the plan. The government then called an election early, and their main message was "Maîtres chez nous" (meaning "Masters in our Own Homes"). This idea had a strong feeling of Quebec pride and independence.

The government was re-elected on November 14, 1962. Lévesque then moved forward. On December 28, 1962, Hydro-Québec offered to buy all the shares of 11 private companies. They offered a price slightly higher than the market value. These companies included Shawinigan Water & Power, Quebec Power, and others. After some thought, the companies told their shareholders to accept the C$604 million offer.

Besides these 11 companies, most smaller electric groups and city-owned utilities were also taken over. They all joined Hydro-Québec. On May 1, 1963, Hydro-Québec became the largest electricity company in Quebec.

In 1962, the US government loaned Quebec $300 million. This money helped buy the independent power companies. In 1964, British Columbia also loaned Quebec $100 million, with $60 million going to Hydro-Québec.

Big Projects of the 1960s and 1970s

After taking over all the private companies in 1963, Hydro-Québec had three big challenges. First, it had to combine all the new companies into one system. Second, it had to make sure all the different electricity networks worked together. Many of these networks were old and needed fixing. Third, it had to upgrade the Abitibi system from 25 to 60 Hertz (a measure of electrical frequency).

All this was happening while the Manic-Outardes Complex was being built. This huge project was on the North Shore of Quebec. By 1959, thousands of workers were building 7 new hydroelectric power stations. This included the Daniel-Johnson Dam, which was the largest of its kind in the world. Building on the Manicouagan and Outardes rivers finished in 1978.

These massive projects created a new problem: how to send huge amounts of electricity from power stations hundreds of kilometers away to cities in southern Quebec in a cheap way. A young engineer named Jean-Jacques Archambault came up with a plan to build 735 kV power lines. This was a much higher voltage than what was used at the time. Archambault kept pushing his idea and convinced his colleagues and equipment makers that it would work. The first 735 kV power line started working on November 29, 1965.

Churchill Falls Power Station

When Hydro-Québec bought the Shawinigan Water & Power Company, it also got a 20% share in a planned hydroelectric project at Churchill Falls in Labrador. This project was led by a group of banks and companies called Brinco.

After many tough talks, a deal was made on May 12, 1969, to build the power plant. The agreement meant Hydro-Québec would buy most of the plant's electricity at a very low price for 65 years. Hydro-Québec also agreed to share some of the financial risks. In return, it got a 34.2% share in the company that owned the plant. The 5,428-megawatt Churchill Falls power station started producing electricity on December 6, 1971. All 11 of its turbines were working by June 1974.

After the 1973 oil crisis, the Newfoundland government was unhappy with the deal. It bought all the shares in the Churchill Falls company that Hydro-Québec didn't own. Newfoundland then asked to change the contract, but Hydro-Québec refused. After a long legal fight, the Supreme Court of Canada said the contract was valid twice, in 1984 and 1988.

Considering Nuclear Power

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Hydro-Québec thought about building nuclear power plants to meet Quebec's energy needs. The company worked with Atomic Energy of Canada Limited (AECL) to build two CANDU nuclear reactors. These were the Gentilly nuclear generating stations in Bécancour.

The first reactor, Gentilly-1, was built between 1966 and 1970. It was a 266-megawatt unit. But it was almost never used for commercial operation. In 1980, AECL stopped using the plant, and they still own it.

The second plant, Gentilly-2, was a 675-megawatt unit. It started working in 1983 after 10 years of building. In 2008, the Quebec government and Hydro-Québec decided to fix up Gentilly-2 to make it last until 2035. This would cost C$1.9 billion. However, on October 3, 2012, the Quebec government decided to shut down Gentilly-2 instead. The cost to shut it down was estimated at $2 billion, while fixing it up had become much more expensive, at $4.3 billion. The plant closed on December 28, 2012.

"The Project of the Century": James Bay

Almost exactly a year after he was elected in April 1970, Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa started a huge project. He hoped it would create 100,000 new jobs. On April 30, 1971, he announced plans for a 10,000-megawatt hydroelectric complex in the James Bay area. After looking at three options, Hydro-Québec and the government chose to build three new dams on La Grande River. These were named LG-2, LG-3, and LG-4.

Building such a massive project in a harsh, remote area was very challenging. The project leader, Robert A. Boyd, also had to deal with opposition from the 5,000 Cree people who lived in the area. They were very worried about how the project would affect their traditional way of life. In November 1973, the Crees got a court order that temporarily stopped the building of roads and other basic structures needed for the dams. This forced the Bourassa government to talk with them.

After a year of difficult talks, the Quebec and Canadian governments, Hydro-Québec, and the Grand Council of the Crees signed the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement on November 11, 1975. This agreement gave the Crees money and control over health and education in their communities. In return, they allowed the project to continue.

Between 14,000 and 18,000 workers were employed at various James Bay construction sites from 1977 to 1981. The LG-2 power station, which is underground and can produce 5,616 megawatts, started working on October 27, 1979. It is the most powerful underground power station in the world. The station, dam, and reservoir were renamed in honor of Premier Bourassa after he passed away in 1996. The first part of the project was finished when LG-3 started working in June 1982 and LG-4 in 1984. A second part of the project was built between 1987 and 1996, adding five more power plants.

The 1980s and 1990s: New Challenges

After two decades of strong growth, the late 1980s and 1990s were harder for Hydro-Québec. Especially when it came to environmental concerns. A new hydroelectric project and a high-voltage power line to send electricity to New England faced strong opposition. This opposition came from the Crees and environmental groups in the US and Canada.

To send electricity from the James Bay Project to New England, Hydro-Québec planned to build a 1,200 km (746 mi) long direct current power line. This line could carry 2,000 megawatts. Building the line went smoothly, except where it had to cross the Saint Lawrence River.

Because of strong opposition from local people to other options, Hydro-Québec built a 4 km (2.5 mi) tunnel under the river. This cost C$144 million and delayed the project by two and a half years. The line finally started working on November 1, 1992.

Great Whale Project Controversy

Hydro-Québec and the Bourassa government faced a much tougher challenge with the next project in northern Quebec. After being re-elected in 1985, Robert Bourassa announced another hydro project in the James Bay area. This C$12.6 billion Great Whale Project would build three new power stations. They would produce 3,160 megawatts and 16.3 terawatt-hours of energy each year.

The plan immediately caused a lot of debate. Just like in 1973, the Cree people opposed the project. They filed lawsuits against Hydro-Québec in Quebec and Canada to stop it. They also worked in many US states to prevent the sale of electricity from the project there.

The Crees successfully got the Canadian government to start a separate environmental review. This helped delay construction. Cree leaders also got support from US environmental groups. They launched a public campaign in the US and Europe, criticizing the Great Whale Project, Hydro-Québec, and Quebec in general.

The Cree campaign was successful in New York State. The New York Power Authority canceled a US$5 billion electricity contract it had signed with Hydro-Québec in 1990. Two months after the 1994 election, the new Premier, Jacques Parizeau, announced that the Great Whale Project was stopped. He said it was not needed for Quebec's energy needs.

After the Great Whale project was canceled, Hydro-Québec had to find new ways to get electricity. In September 2001, Hydro-Québec announced it would build a new gas power plant called Centrale du Suroît in Beauharnois. They said it was needed to make sure there was enough electricity, especially if water levels in their reservoirs were low.

However, this announcement came at a bad time. Canada was discussing joining the Kyoto Protocol, which aimed to reduce carbon emissions. The Suroît plant would have increased Quebec's carbon dioxide emissions by almost 3%. People were very upset. A poll in 2004 showed that two out of three Quebecers were against it. So, the Jean Charest government stopped the project in November 2004.

Dealing with Natural Disasters

During this time, Hydro-Québec also faced three major problems with its electricity system caused by natural disasters. These events showed a big weakness: the long distances between where electricity was made and where it was used in southern Quebec.

Two Blackouts in One Year

On April 18, 1988, at 2:05 AM, all of Quebec and parts of New England and New Brunswick lost power. This happened because of equipment failure at a key substation on the North Shore. The blackout lasted up to 8 hours in some areas. It was caused by ice on transformer equipment.

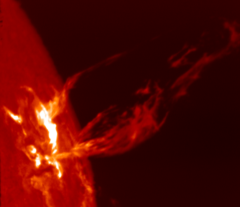

Less than a year later, on March 13, 1989, at 2:44 AM, a large solar storm caused changes in the Earth's magnetic field. This tripped circuit breakers on the power network. The James Bay network shut down in less than 90 seconds. This caused Quebec's second blackout in 11 months. The power outage lasted 9 hours. After this, Hydro-Québec started a program to reduce risks from these types of storms.

The Great Ice Storm of 1998

In January 1998, five days of heavy freezing rain caused the biggest power failure in Hydro-Québec's history. The weight of the ice broke 600 km (373 mi) of high-voltage power lines. It also broke over 3,000 km (1,864 mi) of smaller distribution lines in southern Quebec. Up to 1.4 million Hydro-Québec customers had no power for up to five weeks.

Part of the Montérégie region, south of Montreal, was hit the hardest. It became known as the Triangle of Darkness. Ice built up to over 100 mm (4 in) in some places. Customers on the Island of Montreal and in the Outaouais region also lost power. This was a big problem because many Quebec homes use electricity for heating.

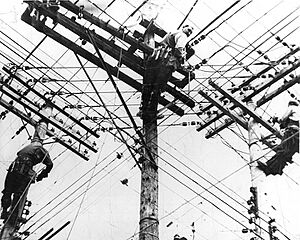

Hydro-Québec immediately called all its workers, even retired ones. They also asked for help from other electricity companies in Eastern Canada and the northeastern US. The Canadian Army also helped restore power. More than 10,000 workers had to rebuild a large part of the network, one power pole at a time. At the worst point, on January 9, 1998, the island of Montreal was powered by only one single line. The situation was so serious that the Quebec government temporarily cut power to parts of downtown Montreal to keep the city's drinking water supply working.

Electricity was fully restored on February 7, 1998, 34 days later. The storm cost Hydro-Québec C$725 million in 1998. Over C$1 billion was invested in the next ten years to make the power grid stronger against similar events.

Hydro-Québec in the 2000s

New Hydroelectric Projects

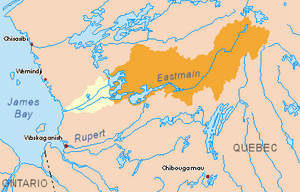

After a break in the 1990s, Hydro-Québec started building again in the early 2000s. Recent projects include the Sainte-Marguerite-3 (SM-3) station in 2004 (884 megawatts), Toulnustouc in 2005 (526 megawatts), Eastmain-1 in 2007 (480 megawatts), Peribonka (385 megawatts), and Mercier in 2008 (50.5 megawatts). Rapides-des-Cœurs (76 megawatts) and Chute-Allard (62 megawatts) were completed in 2009.

On February 7, 2002, Premier Bernard Landry and Ted Moses, the head of the Grand Council of the Crees, signed an agreement. This agreement allowed new hydroelectric projects to be built in northern Quebec. The Paix des Braves agreement clarified parts of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. It gave the Cree Nation C$4.5 billion over 50 years. It also set up special rules for wildlife and forests. And it made sure Cree businesses and workers would get a share of the jobs from future construction projects.

In return, the Cree nation agreed not to challenge new construction projects in the area. This included the Eastmain-1 power station and partly changing the flow of the Rupert River to the Robert-Bourassa Reservoir. This was agreed upon with rules to protect nature and local communities.

Building on the first 480-megawatt plant started in spring 2002. This included a road linking the project site to a substation 80 km (50 mi) away. Besides the plant, the project needed a large dam, 33 smaller dams, and a spillway. The three power units of Eastmain-1 started working in spring 2007. The plant produces 2.7 terawatt-hours of electricity each year.

These projects are part of Quebec's energy plan for 2006–2015. This plan aimed to develop 4,500 megawatts of new hydroelectric power. This included the 1,550 MW Romaine River complex, which has been under construction since May 2009. The plan also aimed to add 4,000 megawatts of wind power, increase electricity exports, and create new energy efficiency programs.

Hydro-Québec's Growth Over Time

| Power Produced (in megawatts) |

Electricity Sold (in terawatt-hours) |

Home Customers (in thousands) |

Employees | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944 | 616 | 5.3 | 249 | n/a |

| 1949 | 810 | 6.2 | 295 | 2,014 |

| 1954 | 1,301 | 8.1 | 362 | 2,843 |

| 1959 | 2,906 | 13.7 | 475 | 3,439 |

| 1964 | 6,562 | 35.3 | 1,322 | 10,261 |

| 1969 | 9,809 | 46.8 | 1,567 | 11,890 |

| 1974 | 11,123 | 78.3 | 1,842 | 13,679 |

| 1979 | 14,475 | 97.0 | 2,108 | 17,880 |

| 1984 | 23,480 | 123.8 | 2,446 | 18,560 |

| 1989 | 25,126 | 137.6 | 2,802 | 19,437 |

| 1994 | 30,100 | 157.0 | 3,060 | 20,800 |

| 1999 | 31,505 | 171.7 | 3,206 | 17,277 |

| 2004 | 33,892 | 180.8 | 3,400 | 18,835 |

| 2008 | 36,429 | 191.7 | 3,603 | 19,297 |

| 2015 | 36,912 | 201.1 | n/a | 19,794 |

See also

- Montreal Light, Heat & Power

- Shawinigan Water & Power Company

- Gatineau Power Company

- James Bay Project

- Hydro-Québec's electricity transmission system

- Timeline of Quebec history

- Nationalization of Electricity in Quebec

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |