History of Over-the-Rhine facts for kids

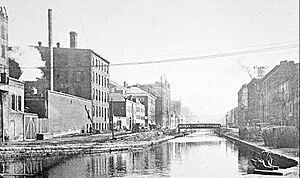

The history of Over-the-Rhine is a long and interesting story, much like the history of Cincinnati itself. This neighborhood has seen many changes in its people and buildings over the years. The name "Over-the-Rhine" comes from the Miami and Erie Canal. People used to joke that crossing the canal was like crossing the Rhine River in Germany. In 1853, a traveler named Ferenc Pulszky wrote that Germans lived "across the Miami Canal, which is, therefore, here jocosely called the 'Rhine'." Later, in 1875, writer Daniel J. Kenny noted that "Germans and Americans alike love to call the district 'Over the Rhine'."

Contents

A German Home in Cincinnati

In the mid-1800s, thousands of German people came to the United States. Many were refugees from the revolutions of 1848 in the German states. In Cincinnati, they found affordable homes north of the Miami and Erie Canal. This area was outside the city limits until 1849. The road marking the city's edge was called Liberty Street. It separated the city from the "Northern Liberties," where city laws didn't apply. This meant it attracted businesses like gambling houses and dance halls that weren't allowed in Cincinnati proper.

By 1850, about 63% of Over-the-Rhine's population was from German states like Prussia, Bavaria, and Saxony. The neighborhood quickly became very "German" in its feel. The new residents brought their own customs, habits, and different German dialects. They had various religions, jobs, and social classes. Several German newspapers, like the Volksfreund, Volksblatt, and Freie Presse, served the community.

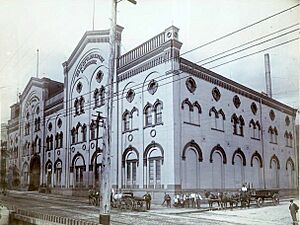

German business owners also built a successful brewing industry. This industry became strongly linked to Over-the-Rhine and Cincinnati. Many breweries, such as Jackson Brewery and Christian Moerlein Brewing Company, were located near McMicken Avenue and the canal. By 1880, Cincinnati was known as the "Beer Capital of the World," with Over-the-Rhine at its heart.

During the 1800s, Over-the-Rhine was Cincinnati's top entertainment area. People described it as a place for "pleasure and a holiday." One writer in 1875 said that stepping across the canal was like entering a different world. He noted that people there were "more readily happy, more readily contented, more easily pleased, far more closely wedded to music and the dance."

Before the incline system was built in the 1870s, Cincinnati was very crowded. About 32,000 people lived per square mile. For comparison, in 2000, it was about 3,879 people per square mile. Horsecars were the main way to get around, but they couldn't go up the steep hills. The new incline system allowed people to build homes on the hills. Only those who could afford it moved there, as demand for new housing was high.

Throughout the 19th century, Cincinnati faced outbreaks of diseases like cholera and typhoid fever. These often spread through river travel and poor sanitation. Thousands died, causing widespread fear. Many believed that vapors from the canal caused illnesses. This idea was later used to argue for turning the canal into a subway and parkway. Besides overcrowding and disease, people in the river basin also dealt with floods, open sewers, and industrial pollution. Riots also occurred in Over-the-Rhine in 1853, 1855, and 1884. Those who could afford it moved to the new suburbs on the surrounding hills.

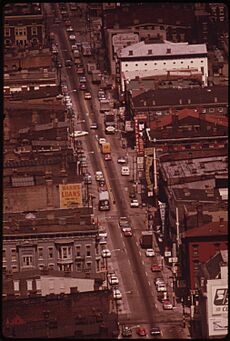

The neighborhood, especially upper Vine Street, was filled with saloons, restaurants, shooting galleries, arcades, gambling places, dance halls, and theaters.

Around 1900, the neighborhood's population reached its highest point with 45,000 residents. About 75% of them were German-Americans. By 1915, wealthier people started leaving the crowded city for the suburbs. Fewer new immigrants moved in, as many were drawn to growing industrial cities in the Great Lakes region. Over-the-Rhine became one of several older neighborhoods that formed a ring of less prosperous areas around the city's main business district. Many thought it would eventually disappear as the business district grew.

Changes and Challenges

Many German-Americans felt proud of their homeland. They even celebrated early victories by Germany during World War I. Cincinnati's German newspapers, the Volksblatt and Freie Presse, were very vocal about this. As the United States seemed more likely to join the war, some Americans, especially those who disliked immigrants, questioned the loyalty of ethnic Germans. After the US entered the war, anti-German feelings grew across the country.

In 1917, when the US declared war on Germany, half of Cincinnati's residents could speak German. Many spoke only German. The community had German schools and church services in German. In 1918, the government made German men who were not US citizens register as "alien enemies." The New York Times reported that going "over the Rhine" meant entering a place where "all English was left behind." The city even changed all German street names. For example, Bremen Street became Republic, and Hanover became Yukon Street. German-language schools were closed, teachers were fired, and German classes were banned from public schools. The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County removed all German books. Many German-Americans changed their names to avoid problems. Some businesses with German names changed them too. Cincinnati's German heritage was suppressed until after World War II.

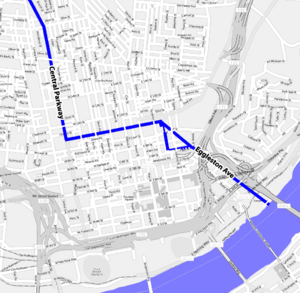

The Miami and Erie Canal became outdated for transportation. The city stopped using it in 1877. The canal was like an open sewer in the city because sanitation systems were poor. In 1920, the city drained the canal and began building the Cincinnati Subway in its bed. Central Parkway, which follows the canal's path, runs over the subway tunnels. However, the subway construction stopped halfway. The city faced unexpected inflation after World War I. Then, the Great Depression, World War II, and the rise of cars prevented the city from ever finishing the subway.

Starting in the 1920s, the city government tried to improve Cincinnati. They planned to clear older, run-down buildings and homes. These areas were called "slums" and were seen as problems that could spread to other neighborhoods. A 1925 plan suggested tearing down homes in the West End and Over-the-Rhine. It also proposed using these areas only for businesses, industries, and public buildings. However, due to the stock market crash and the Great Depression, these plans were delayed.

In the 1930s, there were attempts to get loans to clear the West End and Over-the-Rhine, but they all failed due to a lack of local money.

New Residents and Challenges

In the 1940s, the booming industrial economy during World War II attracted many people from Appalachia to cities like Cincinnati. In the 1950s, machines took over much of the mining work, and oil became more popular. This caused a sharp drop in demand for coal. Looking for work, coal miners from Kentucky and West Virginia moved to Cincinnati. They settled in older neighborhoods like Lower Price Hill and Over-the-Rhine, where housing was cheaper. Both areas were also close to the industrial Mill Creek Valley, making it easy to walk to work.

By the 1960s, so many "mountaineers" (Appalachian migrants) lived in Over-the-Rhine that the city planned to use it as a "port of entry" for all white Appalachian migrants. Appalachians were seen as a unique group with special needs. They sometimes faced unfair judgments and negative stereotypes. Some struggled in the city because they were not used to formal education or modern medicine. To celebrate their culture, the city started the first Cincinnati Appalachian Festival in 1971. It is still held every year, now at Coney Island.

A Changing Community

In the 1950s and 1960s, the city built the Mill Creek Expressway (now part of I-75) for the growing number of cars. This construction, along with the Queensgate industrial area and public housing projects, led to the destruction of the West End. The West End was a historic black neighborhood. More than 50,000 mostly black and low-income residents were forced to move. Many found homes in nearby Over-the-Rhine, living alongside poor and working-class white Appalachians. This sometimes led to conflicts between young men from both groups.

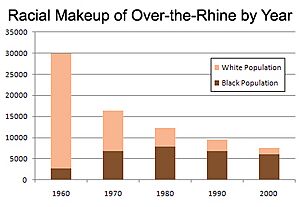

Over-the-Rhine became more of a black neighborhood as white residents moved to the suburbs. This "white flight" happened because newer homes, more space, and easier commutes were available. Some jobs also moved to the suburbs. The black population in Over-the-Rhine reached its highest point of about 7,300 in 1980. However, this was still much smaller than the 27,000 white residents who lived there just 20 years earlier. From 1980 to 2000, both black and white residents left Over-the-Rhine, but white residents left at a faster rate.

Focus on Social Services and History

In the 1950s and 1960s, the city created many social service centers in Over-the-Rhine. However, they focused their major rebuilding projects on the central business district. By the late 1970s, the city wanted to invest in Over-the-Rhine through historic preservation. They hoped to attract wealthier residents. But community organizers disagreed. They worried that uncontrolled rebuilding would force poor residents out of their homes.

Buddy Gray, who ran the Drop Inn Center homeless shelter, became a leader of the "Over-the-Rhine People's Movement" (OTRPM). This group opposed displacement. OTRPM wanted new job opportunities for residents. They supported mixed-income and private development, but only if there were rules to protect current residents from being pushed out. Gray's leadership gave a voice to Over-the-Rhine's poor. He pushed the city to create more permanent low-income housing to prevent displacement.

Historic preservationists saw Over-the-Rhine as a special place with "irreplaceable architectural and historic resources." They wanted it added to the National Register of Historic Places to help protect it. Gray was against this. He believed it would lead to tax credits for developers, which would cause the poor to be displaced. Preservationists argued that displacement came from a lack of investment, not from historic listing. They also pointed out that with many vacant homes, there was room for both middle and upper-income housing. They also said that the National Register listing could provide funds for low-income housing. Groups like the Over-the-Rhine Foundation and Chamber of Commerce supported preservation.

In 1980, at a public meeting about adding Over-the-Rhine to the National Register, Buddy Gray gathered about 250 protesters. Gray and his supporters delayed the decision for three years. In 1983, Over-the-Rhine was rejected by a close vote. However, supporters appealed the decision. Over-the-Rhine was finally added to the National Register in May 1983.

Buddy Gray made expanding low-income housing his main goal. In 1985, Gray pushed a plan through the city council. It allowed some wealthier residents to move in, but only after permanent low-income housing was secured. The plan set aside "a minimum of 5,520 [low-income housing] units" out of 11,000 possible units. This number was almost the same as the occupied units. Public money would not be spent on upper-income housing until this goal was met. Also, a housing rule meant low-income housing could not be torn down unless it was replaced.

Jim Tarbell, a strong opponent of Gray's plan, warned that it would keep Over-the-Rhine as "a predominantly black enclave of poverty and despair." But the City Council ignored him, thinking the plan was a good compromise. Preservationists found little local support. Other Cincinnati neighborhoods worried that displacement would move the city's poor, and crime, closer to their homes. Over the next seven years, the plan did not create a balance in its population. It also failed to attract businesses or industries. By 1990, Over-the-Rhine had 2,500 government-supported low-income housing units (compared to almost none in 1970). It had become one of the most struggling areas in the United States. The neighborhood had very high poverty and unemployment rates. The average household income was about $5,000 a year. About 84% of residents were considered low-income, and over 95% of all homes were rentals.

No one seriously challenged the 1985 plan until 1992. Housing Opportunities Made Equal (HOME) criticized Over-the-Rhine. They said it was becoming a "permanent low income, one-race ghetto." In 1993, Over-the-Rhine's housing policy changed after several small business owners sued. They called the policy "racial and economic segregation." The city settled the lawsuit and agreed to remove low-income housing as Over-the-Rhine's top priority.

In 1996, the city asked the Urban Land Institute (ULI) to study Over-the-Rhine and create a plan for its improvement. ULI suggested forming a "Over-the-Rhine Coalition" to help different groups reach an agreement. Gray refused to join unless specific demands were met. He believed the ULI study was meant to stop his efforts to keep low-income housing. ULI experts questioned if Gray had too much power over City Hall. They asked the city if they should continue funding Gray, who they saw as "an impediment to revitalization." Later that year, Buddy Gray was sadly shot and killed by a mentally-ill homeless man he had helped. After Gray's death, his supporters could not find another leader like him. The Over-the-Rhine Coalition was then formed.

Gray's work continued through the Drop Inn Center and ReSTOC, his low-income housing cooperative. ReSTOC owned many properties in the neighborhood. At one point, it owned 71 buildings in Over-the-Rhine. However, the non-profit struggled to pay for the upkeep of all its properties. In 2001, former mayor Charlie Luken said ReSTOC owned "the most blight in Over-the-Rhine." Critics accused ReSTOC of holding onto properties to prevent new development. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that despite receiving millions of dollars to develop low-income housing, ReSTOC "actually reduced the number of occupied apartments." In 2002, the city made ReSTOC sell some properties. The money from these sales was to be used to improve the remaining properties. ReSTOC later joined with another non-profit to form Over-the-Rhine Community Housing.

New Life and Growth

In the 1980s, struggling artists, mostly white, found vacant buildings and cheap rents on Main Street. A bar and nightclub called Neons opened in 1984. It became very popular and helped start the Main Street Entertainment District in the 1990s. Coffee shops, art galleries, breweries, and bars began opening on the six blocks between Central Parkway and Liberty Street. Main Street became a lively arts scene. However, as the street grew popular, landlords raised rents. Many artists eventually moved to Northside. At its peak, Main Street's clubs, restaurants, and bars attracted nearly a million visitors a year.

In the late 1990s, Main Street became a hub for internet companies, nicknamed "Digital Rhine." This was partly due to cheap rents and its closeness to other businesses. The area had at least 10 internet startups. One startup was even sold to eBay in 1999 for $85 million.

Modern Redevelopment

After the 2001 Cincinnati riots, Mayor Charlie Luken decided the city needed a new approach to development. He met with Procter & Gamble CEO A.G. Lafley. Together, they announced the creation of a nonprofit organization called Cincinnati Center City Development Corporation (3CDC). This group, made up mostly of Cincinnati's business community, raised millions of dollars. The money came from city grants, company donations, and federal tax credits. In 2003, a landlord who went bankrupt auctioned off 1,600 low-income apartments. Cincinnati's wealthy businesses and charities began buying entire blocks. 3CDC was the biggest buyer. They immediately faced opposition from homeless advocates who said they were displacing the poor. However, 3CDC stated that "at least 90 percent" of the buildings they bought were empty. Since 3CDC was not a government agency, it was harder to stop or slow down their projects compared to those from City Hall.

Since 2004, 3CDC has invested $84 million in 152 very run-down buildings and 165 empty plots of land. In April 2009, 3CDC reported that 70% of the 100 condos in the Gateway Quarter had been sold. About 80% of the buyers were 35 years old or younger. By February 2010, 3CDC had redeveloped nearly 200 condominiums and more than 30 new storefronts. Even with a difficult housing market, 60% of these were sold. 3CDC planned to invest $164 million in redevelopment projects in 2010, mostly in Over-the-Rhine. By 2012, they expected to complete 150 new apartments, more renovated condos, and new office spaces.

In 2004, the Art Academy of Cincinnati moved to 12th and Jackson streets in Over-the-Rhine. A new building for the School for Creative and Performing Arts opened in 2010. This $80 million facility is the only K-12 arts school in the United States. The Emery Theatre, a historic venue, underwent a $3 million renovation and reopened in 2011. The Cincinnati Streetcar, the city's first streetcar line since the 1950s, is being built and will run through downtown and Over-the-Rhine. This streetcar line is expected to bring $1.9 billion in benefits to the city. A $14 million expansion and renovation of Washington Park was completed in 2012, including an $18 million underground parking garage. Cincinnati Public Schools is renovating the historic Rothenburg School to replace a school that was torn down at Washington Park. In 2004, the City of Cincinnati finished a $16 million renovation of Findlay Market. It was 47% occupied then, but by 2010, it was 100% occupied and still growing.

Between 2004 and 2009, crime in the Gateway Quarter dropped by almost 50%. Between 2008 and 2010, 47 new businesses opened in the Gateway Quarter. In 2010, new businesses started appearing in the neighborhood because a casino was planned nearby. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer in 2012, "in just six years, developers have moved Over-the-Rhine from one of America's poorest, most run-down neighborhoods to among its most promising." The Urban Land Institute also called Over-the-Rhine "the best development in the country right now."