History of Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh longshoremen, 1863–1963 facts for kids

In the late 1870s, the Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh communities lived on the North Shore of Burrard Inlet. As the city of Vancouver grew, their lands and way of life were affected. New cities and industries meant their traditional ways of making a living, like fishing and hunting, became harder. Government rules also limited their access to land and water. Because of these changes, many Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh people started working for wages.

One important job from 1863 to 1963 was longshoring. This meant loading and unloading ships. By the early 1900s, this work became very important for their income. In 1906, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh longshoremen created the first union on the Vancouver waterfront. It was called Local 526. This union later changed names several times, becoming ILA Local 38-57, the ILHA, and the NVLA. These unions helped protect their jobs and interests as more people competed for work.

Contents

A Look at Early Life in the Vancouver Area

Human settlements in the Lower Fraser region, where Vancouver is today, began 8,000 to 10,000 years ago. This was after the last ice age. The Coast Salish people lived here before salmon arrived in the river about 4,500 to 5,000 years ago. Trees like Douglas fir, western hemlock, and western red cedar also grew around this time.

According to historian Lee Maracle, Burrard Inlet was home to "Downriver Halkomelem" speaking people, the Tsleil-Waututh. They shared the area with the Musqueam people.

European Contact and Its Impact

Europeans first met the indigenous peoples of present-day Vancouver in June 1792. By 1812, the Halkomelem people had survived three major epidemics. These were caused by foreign illnesses like smallpox, which came through trade routes. A 1782 outbreak killed two-thirds of the population. Before these epidemics, it's thought that over 60,000 Indigenous people lived in the Lower Fraser area.

An 1830 census by the Hudson's Bay Company counted 8,954 Indigenous people. However, this count was likely incomplete. The Tsleil-Waututh population dropped to only 41 people by 1812 from a high of 10,000 before contact. The Tsleil-Waututh Nation says fewer than fifteen people remained. Because of this, the Tsleil-Waututh invited the nearby Squamish to live in Burrard Inlet.

Traditional Ways of Life and the Potlatch

Traditionally, the Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh economy followed the seasons. They harvested resources from land and water. Families often had special rights to certain areas for gathering food. Marriages were sometimes arranged to ensure access to these important sites.

The economies of Northwest Coast cultures, including the Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh, used the potlatch system. A potlatch is a special ceremony where wealth is shared. The word "potlatch" comes from a Chinook Jargon word meaning "to give." For the Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh, potlatching is still very important. It is the heart of their culture, politics, economy, and education.

Working for wages, like longshoring, helped support these traditional activities. People could use their earnings to buy goods needed for a potlatch. This shows how they blended new ways of earning money with their old traditions.

Challenges and Government Policies

The Tsleil-Waututh asked Queen Victoria in 1873 to address their land rights. In 1906, Squamish leaders traveled to England to speak with King Edward VII about similar concerns. Their traditional ways of life were being pushed aside.

The Canadian government also had policies to make Indigenous people adopt European ways. This included banning the potlatch from 1884 to 1951. They also set up residential schools from the 1870s to 1996. These schools forced Indigenous children away from their families and cultures. The Indian Act also brought many changes and restrictions.

Who Were the Aboriginal Workers on the Waterfront?

On the Vancouver waterfront, it was sometimes hard to tell exactly which Indigenous groups were working. Indigenous communities often moved within a network of social and economic connections. White society often saw all Aboriginal workers as simply "Indian." But in reality, they were many different cultural groups.

Most Aboriginal longshoremen between 1863 and 1945 were members of the Squamish Nation. However, other Aboriginal groups, like the Musqueam, also worked in longshoring and sawmills. The term "Indian" on the waterfront was broad. It included people born to Squamish parents, and also Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal men who married Squamish women. Other workers from different backgrounds also joined these longshoremen gangs.

Some workers on Vancouver's waterfront were Kanakas. These were Indigenous workers from Hawaii. They had a long history of marrying and connecting with Native groups along the B.C. coast. For example, longshoreman William Nahanee was part Squamish and part Hawaiian. Some Aboriginal longshoremen, like Harry Jerome (who was Tsimshian), joined Squamish society through marriage.

Until recently, the Tsleil-Waututh were often identified as part of the Squamish Band. Their name means "People of the Inlet." They lived on Burrard Indian reserve #3, separate from the Squamish reserves. However, they were never officially combined with the Squamish. This confusion might have happened because many Tsleil-Waututh started speaking the Squamish language after the first smallpox epidemic.

Because of this, Tsleil-Waututh longshoremen were often thought of as Squamish. For example, Chief Dan George was a Tsleil-Waututh, but a book said he became chief of the Squamish band. Today, the Tsleil-Waututh Nation has about 500 members. The Squamish Nation has about 3,800 members.

How Aboriginal People Started Working in Lumber Longshoring

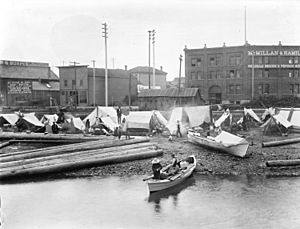

In 1863, a sawmill opened on Burrard Inlet. This was a great spot because it had lots of cedar and fir trees, and a deep, safe harbor. At first, Squamish people visited Burrard Inlet seasonally for hunting, fishing, and trade. After the mill opened, more Squamish workers moved to the area. They started to include wage labor in their traditional seasonal economy.

Besides their traditional fishing, hunting, and gathering, the Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh began commercial activities. This included industrialized fishing using modern tools like the gill net. Fish cannery workers were mostly Aboriginal until the 1870s and 1880s. New jobs like forestry (logging, mill work, and longshoring) were often short-term. Aboriginal men would work intensely for short periods. This allowed them to also work in other seasonal jobs, like picking hops.

Forestry work was done only by men. Logging was short-term, with men working for weeks before returning to cities. Mill work and longshoring were more continuous. However, there was a shortage of workers until the 1900s. This meant Native workers could work when it suited their own needs. In 1893, an "Indian Agent" noted that many Squamish men worked in Vancouver's lumber mills.

As sawmill work became more specialized, Aboriginal involvement decreased. Like other groups, the Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh focused on longshoring. Many Aboriginal workers already knew about handling lumber from logging and sawmill work. This made the move to longshoring easy for them. They quickly became familiar with the waterfront work.

Working on the Docks: Handling Lumber

In the early 1900s, four to six groups of mostly Aboriginal longshoremen worked on the docks each day. Depending on the ship's size, between forty and ninety Aboriginal longshoremen could be found moving lumber. By the early 1920s, this number grew to about 125 workers daily.

Longshoring lumber was hard and often dangerous work. But it paid a bit more than sawmill work. It also allowed workers to work sometimes and do other activities when they wanted. Longshoring involved moving raw logs and cut lumber into ships. In the early days, logs were moved by hand through openings or slid down ramps into the ship's hold. Milled lumber was lifted by a cable using a steam-powered engine. These engines were called "donkeys."

By the 1920s, steam-powered ships replaced sailing ships. This meant more machines were used, like winches and cranes. Longshoring lumber was physically demanding, but it was also a skilled job. Workers developed special roles within each work group. Knowing how to move lumber on and off a ship required a lot of skill.

For example, Chief Dan George, a famous Tsleil-Waututh longshoreman, said some timber was ninety feet long. Ships could take three to six months to load. Edward Nahanee, a Squamish longshoreman, said he could tell where each timber would go as it landed.

This special skill in fitting lumber into ships earned Aboriginal workers respect. It also led to the idea that their race made them naturally good at this work. One dock worker called Native longshoremen "the greatest men who ever worked the lumber." However, white longshoremen were often given better jobs above deck. To deal with this, Aboriginal workers used the Squamish language. This helped them feel connected and allowed them to talk privately away from white employers.

Around 1900, some Squamish men, like Dan Paull and Chief Joseph Capilano, became foremen. This allowed them to hire their friends and family for longshoring jobs.

Unions and Activism: 1906–1923

In the early 1900s, the forest industry was divided by ethnicity. Most logging camp workers were white. But most sawmill workers were of Asian origin, especially Sikhs from India. This division made it hard for unions to fight for workers' rights. Existing white unions often refused to let "Indian Gangs" join.

The first organized effort by Vancouver longshoremen was in 1888. Some joined the Knights of Labor. In 1906, about fifty to sixty lumber handlers, mostly Squamish, formed Local 526 of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). This was the first union on the Vancouver waterfront. It was informally called the "Bows and Arrows," showing its Indigenous roots. Meetings were held on the Mission Reserve in North Vancouver. After a difficult strike in 1907, the union broke up.

1906 was an important year for Coast and Interior Salish communities. Besides forming Local 526, they chose three chiefs to go to London, England. They wanted to ask King Edward VII directly about their land rights. Chief Capilano was one of these chiefs. He met with King Edward.

Even though they didn't get their land claims settled, this trip showed how different Indigenous communities could unite. Longshoring helped make this trip possible. Chief Capilano paid for his journey to England with his longshoring wages. In 1928, Chief Capilano also traveled to Ottawa to meet with Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier about First Nations issues.

On March 30, 1912, mostly white longshoremen formed the Vancouver Local of the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA). In 1913, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh workers formed their own ILA local, Local 38-57. They decided to close IWW Local 526. This new union was formed partly because Aboriginal longshoremen were learning more English. They also saw that longshoring was changing and becoming more diverse.

William Nahanee became the president of Local 38-57, and his son Edward Nahanee was vice president. By staying independent, Local 38-57 could better represent its workers. This was important as shipping became more global.

Local 38-57 was independent until 1916, when it merged with Local 38-52. The Vancouver ILA then supported the One Big Union, a left-wing union formed in 1919. This continued until the strike of 1923.

Changes on the Waterfront: 1923–1963

The Squamish were at first against the 1923 strike, but they became very involved. William Nahanee, who was on the union's negotiating team, met with striking Aboriginal workers. The long strike of 1923 was a turning point for Aboriginal longshoring unions. After many strikes, the unions became weaker. The Shipping Federation wanted to change how workers were hired, making jobs more permanent instead of casual.

For Aboriginal longshoremen, the strike had a big impact. Most lost their jobs or had very little work. Many were even blacklisted, meaning they couldn't get hired. As a result, many Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh men had to get help from the Squamish band council's trust fund. They also went back to fishing for food and for sale. Chief Dan George left longshoring to log by hand on the Reserve to support his family. Edward Nahanee said, "In ten days it was all over. We lost our jobs and everything."

In 1924, Squamish activist Andrew Paull led Aboriginal longshoremen to form a new union, the ILHA. They wanted to protect Aboriginal jobs and the freedom to work seasonally. However, pressure from the mostly non-Aboriginal ILA weakened the ILHA. It soon had many non-Aboriginal workers and few Aboriginal members.

During the six-month strike of 1935, called the Battle of Ballantyne Pier, many de-unionized Aboriginal men returned to the docks as replacement workers. The union ended the strike on December 9, 1935. Some called these workers "strikebreakers." But as longshoreman Tim Moody said, "My father said my grandfather had been a longshoreman and we had to hang on to what he had started. It was all we had."

After this, the Shipping Federation and the government created the Canadian Waterfront Workers' Association (CWWA). This group banned strikes and required members to be "white" males living in Vancouver for at least a year.

The Shipping Federation also "revitalized" the North Vancouver Longshoreman's Association (NVLA). They wanted to reward Aboriginal longshoremen who had worked during the strike. These Aboriginal workers made up about forty to fifty-five of the eighty-six workers in the Association. They were guaranteed ten percent of the waterfront jobs. Even during the Great Depression, Native workers did well. They controlled the NVLA and got almost equal access to handling all types of cargo. This was different from earlier times when white workers got the non-lumber jobs.

Within this union, Aboriginal longshoremen could work casually. This meant they could also do other jobs alongside longshoring. This continued into the 1930s, 1940s, and early 1950s. In 1953, strict rules were put in place based on seniority (how long someone had worked). One Aboriginal longshoreman who decided to specialize in longshoring in 1953 said, "It was murder at first [to give up fishing]. But now we've got no squawks."

After 1945, Aboriginal involvement in longshoring decreased. By 1954, only twenty-five Aboriginal workers were involved. In 1963, there were thirty-three.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |