History of Ybor City facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ybor City

|

|

|---|---|

|

Neighborhood

|

|

Gateway to Ybor City on 7th. Ave near the Nick Nuccio Parkway

|

|

| Nickname(s):

Florida's Latin Quarter

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Hillsborough County |

| City | Tampa |

| Founded | 1885 |

| Annexed by Tampa | 1887 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Website | http://www.yboronline.com/ |

Ybor City (pronounced EE-bor) is a special neighborhood in Tampa, Florida. It's known for its unique buildings, food, and history. This area was once a busy place where many immigrants came to work and live. It was unusual in the southern United States because it was built almost entirely by people from other countries.

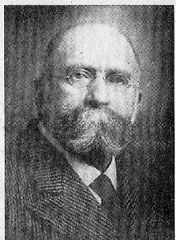

Ybor City started as its own town in 1885. It was founded by cigar makers, led by Vicente Martinez-Ybor. In 1887, it became part of Tampa. The first people to live here were mostly Cuban and Spanish immigrants. They worked in the cigar factories. Later, Italian and Jewish immigrants also moved to Ybor City. They opened shops, farms, and other businesses. These businesses helped the cigar industry and its workers.

Martinez-Ybor built small houses called "casitas" for his workers. He sold these homes at cost to help his employees stay. He also made sure they had medical care. He even paved the streets and sidewalks.

The neighborhood grew very fast in the 1890s. It changed from a wild outpost to a busy city. Ybor City had modern comforts and many different kinds of people. Residents started mutual aid societies, worker groups, and newspapers. They created a lively culture that blended their different backgrounds. This new "Latin" culture was unique to Tampa.

Ybor City kept growing and doing well until the 1920s. Its factories made almost half a billion hand-rolled cigars each year. This earned Tampa the nickname "Cigar City."

The Great Depression in the 1930s hurt Ybor City's economy. People bought fewer expensive cigars. Some factories closed, and others started using machines. This meant fewer jobs and hard times for many families. After World War II, demand for cigars went up. But most factories used machines, so they didn't hire many skilled workers. People moved away for better jobs and homes.

In the 1950s and 60s, the neighborhood continued to shrink. A government program called Urban Renewal tore down many buildings. New roads, like Interstate 4, also cut through the area. Ybor City became neglected and run-down.

Things started to get better in the 1980s. The main business street, 7th Avenue, became popular with artists. By the 1990s, it was a lively place for nightlife and fun. Since 2000, many old buildings have been fixed up. New hotels, offices, and apartments have been built. This has brought more people back to Ybor City for the first time in over 50 years.

Contents

How Ybor City Started

Finding a Home for Cigars

Ybor City began because a businessman from New York City was looking for guava trees. His name was Gavino Gutierrez. In 1884, he came to the Tampa Bay area to find guavas for his company.

The trip was long and hard. The train only went part of the way. Gutierrez had to travel by stagecoach over dirt roads. He didn't find good guavas in Tampa. At that time, Tampa was a small village. Its main jobs were fishing and shipping cattle and citrus.

Gutierrez believed Tampa could grow, especially with new railroads coming. He returned to New York, stopping in Key West, Florida. There, he visited his friend Vicente Martinez Ybor.

Ybor was a Spanish cigar maker. He had a successful business in Havana, Cuba. But he supported Cuban revolutionaries against Spain. He had to leave Cuba in 1868 to stay safe.

Ybor rebuilt his business in Key West. But by the 1880s, it was too expensive to make cigars there. There were also problems with workers and shipping. Other cities offered land to Ybor, but he wasn't happy with their offers.

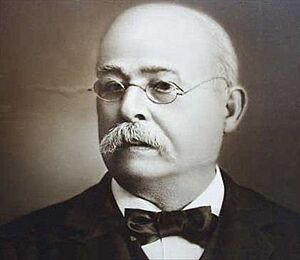

Gutierrez told Ybor about Tampa. Ybor was interested, and so was another cigar maker, Ignacio Haya. They visited Tampa and liked it. Tampa was close to Cuba, so they could easily get tobacco. The warm, humid weather was good for tobacco leaves. And the new railroad would help ship cigars across the U.S. Ybor started talking with Tampa's leaders about moving his factories there.

Making a Deal for Land

In September 1885, Ybor and Haya came to Tampa to make a deal. Ybor wanted to buy 40 acres of land for $5,000. But the owner wanted $9,000. They couldn't agree.

Ybor and Haya were about to leave for Texas. But on October 5, 1885, Tampa's Board of Trade made a new offer. They would pay the extra $4,000 for the land. Ybor quickly agreed. He bought 50 more acres next to it. Haya bought his own land too.

Work began right away. Ybor hired people to clear the land. He asked Gavino Gutierrez to plan the streets for the new town. They decided to call it Ybor City.

There was almost a big problem before the town even started. Tampa's only bank was about to close. Ignacio Haya told the bank manager that he and Ybor would need a local bank. He promised their first payroll would be at least $10,000. The bank manager decided to keep the bank open. This saved the day for the new cigar businesses.

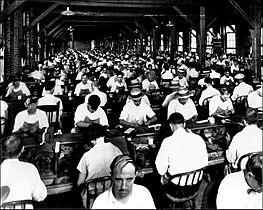

A Special Company Town

Cigar making was more than just a job for the tabaqueros (tobacco workers). The torcedores, who rolled the cigars, saw themselves as artists. Their work was very skilled. Beginners learned for a long time to become master torcedores.

In 1885, Key West had thousands of trained cigar workers. Tampa was a small town with only about 3,000 people. Ybor needed to convince workers to move to this new place. He was known for supporting Cuban independence, which helped. But he needed more to attract workers.

Ybor decided to build a special kind of company town. In most company towns, the company owned everything. But Ybor wanted his workers to own their homes. He also wanted other businesses to buy land and open shops. He hoped this would make Ybor City a great place to live.

Ybor also had good business reasons for this plan. He wanted workers to stay. In Key West, workers often moved between Florida and Cuba. Owning a home would encourage them to settle down in Ybor City. This helped keep the factories busy all year.

Some of the first buildings were 50 small houses called casitas. These were simple wooden homes. Ybor sold them to workers for about $400, just above his cost. Workers could pay for them with small amounts taken from their paychecks.

Ybor also invited other cigar makers to move to his new town. He offered them cheap land and free factory buildings. This was if they promised to create jobs. Even with these offers, it took time for workers and other businesses to come. Many were unsure about moving to a new, wild place.

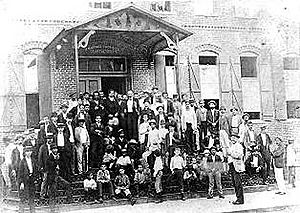

On April 13, 1886, Haya's factory made the first Ybor City cigar. Ybor's factory started a few days later. They had fewer than 100 workers at first.

Later that month, a big fire hit Key West. Hundreds of homes and factories were destroyed. Many cigar workers moved to Tampa for jobs. The fire also made other cigar makers move to Ybor City. This helped the new town grow quickly.

More jobs attracted more people. Cigar workers found steady work in the growing number of factories. More immigrants meant more shops and social events. This cycle of growth continued until the late 1920s. By then, Ybor City had many cigar businesses and thousands of people. It was a thriving cultural center.

By the end of 1886, Ybor's and Haya's factories had made over 1,000,000 hand-rolled cigars. This number would grow much larger in the years to come.

Early Ybor City: A Growing Community

From Wild Frontier to Busy Streets

In 1888, Ybor built a large, three-story brick building. It was the biggest cigar factory in the world at the time. In 1897, he opened The Florida Brewing Company building. This was the tallest building in Tampa until 1913. But at first, Ybor City was a wild and challenging place.

Buildings were mostly made of wood and built quickly. Streets were sandy and hard to travel on. There were no sidewalks or streetlights. People often carried lanterns at night. Wild animals like alligators and bears sometimes wandered into town. One early resident said, "What we found when we arrived was a wild place with swamps everywhere."

Many of the first people in Ybor City were single men. Or they were men who had left their families behind. They came for the many jobs available. These pioneers helped build the community. As one resident said, "they created a city out of the work they did."

By 1887, Tampa leaders were worried about the growing "wild frontier town." They also wanted to collect taxes from Ybor City's successful businesses. So, on June 2, 1887, Tampa took over Ybor City. Ybor himself didn't like this. He felt it would only add rules and paperwork to his company town.

Despite becoming a "city within a city," Ybor City grew. By 1900, it had nice brick buildings and paved streets with streetlights. A streetcar line connected it to Tampa. There were also more cultural and social activities.

Ybor City helped Tampa's money grow a lot. In 1885, Tampa's port collected only $683 in taxes from goods. By 1895, this was over $625,000. This huge increase was mostly because of importing Cuban tobacco and exporting Tampa-made cigars.

Fast Growth and New Cultures

Tampa's population grew rapidly after Ybor City joined it. From less than 800 people in 1880, Tampa grew to over 5,000 in 1890. By 1900, it had almost 16,000 people. Most of these new residents were immigrants who settled in Ybor City.

At that time, U.S. immigration rules were less strict for people from Cuba. Thousands of Cuban and Spanish workers and their families moved between Florida and Cuba. Many Ybor City cigar workers would go back to Cuba for better pay. Because of this, many early residents didn't become American citizens right away. They could live surrounded by their own culture. So, their ties to their home countries stayed strong.

More Diverse People Arrive

The people of Ybor City became more diverse in the late 1880s and early 1890s. Many Italian immigrants started to arrive. Most came from poor towns in Sicily. Some had tried to find work in other U.S. cities first. A small number of Jewish immigrants also arrived around this time. They were mainly from Romania and Germany. They were escaping religious unfairness and looking for jobs.

These new immigrants didn't have cigar-making experience. So, they couldn't easily get jobs in the cigar factories. They learned Spanish, the language of Ybor City, and English. At first, they took any work they could find. Eventually, many opened businesses that served the cigar factories and their workers. They ran grocery stores, clothing shops, and general stores. They also started making cigar boxes and farming vegetables and dairy.

=Cuba Libre (Free Cuba)

Before 1900, most people in Ybor City were Cuban. Spaniards were the second largest group. So, the fight for Cuba's independence from Spain was very important to the community.

This issue caused problems early on. In 1886, Ybor's cigar factory was ready to start. But his Cuban workers refused to work for a Spanish manager. He had a reputation for being anti-Cuban. Only after the manager was replaced did Ybor's workers return.

In the early 1890s, Cuba's fight for freedom grew stronger. Ybor City became a key place for money, supplies, and inspiration. "El dia pa la patria" (one day for the homeland) became a duty for Cubans in Tampa. They donated one day's pay per week to the Cuban cause. Some Italian, Jewish, and even Spanish neighbors also helped.

Jose Marti, known as the "Apostle of Cuban Independence," visited Ybor City many times. He gave powerful speeches to thousands of people. One speech in 1893 helped start the war. Some Tampa residents went to Cuba to fight with Marti. Many died in 1895, the same battle where Marti was killed.

Donations and organizing continued until 1898. That's when the U.S. joined the fight, and it became the Spanish–American War. Tampa became the main port for U.S. troops going to the war. This brought a huge economic boost to Tampa. Over 30,000 troops came, which was double Tampa's population. This brought sudden wealth but also stretched the town's resources.

Cubans in Ybor City welcomed the troops. They believed "Cuba Libre" was finally coming. They were right. The war lasted only a few months. Spain lost most of its remaining colonies.

Some Cubans happily left Tampa for their homeland. They wanted to enjoy their new freedom. But most eventually returned. They found few jobs and much damage from the war. They also realized that American control had replaced Spanish control. Most chose to settle in Ybor City for good.

The "Golden Age": 1902–1929

By the early 1900s, people in Ybor City saw Tampa as their permanent home. Before, many thought it was just a temporary place to work.

One big reason was the good quality of life. Ybor City had everything new arrivals needed. There were jobs, shops, schools, and churches. Most importantly, there were other immigrants who shared their language and customs. Unlike many immigrant areas in the U.S. at that time, Ybor City was not a slum.

The "Latin" residents created a lively community. It mixed Cuban, Spanish, Italian, and Jewish cultures. A visitor called Ybor City "a colorful, screaming, shrill, and turbulent world." The neighborhood had unique red brick buildings with iron balconies. A local food style also appeared, including dishes like the deviled crab.

It took more than pride to turn a wild village into a thriving neighborhood. It took money from a successful industry. In the early 1900s, cigar manufacturing made Tampa grow and prosper. Cigar workers, especially skilled rollers, earned good wages. They could afford to shop in downtown Tampa and Ybor City's commercial area on 7th Avenue. The cigar worker culture valued professionalism and enjoying "the finer things in life."

By making hundreds of millions of hand-rolled cigars each year, Ybor City's workers lived well. They also brought millions of dollars into local businesses and the city government. In 1929, right before the Great Depression, they made 500,000,000 cigars.

Mutual Aid Societies: The Heart of Ybor City

Mutual aid societies, also called social clubs, were very important in Ybor City. They helped improve life for residents. The most famous ones were the Deutscher-Americaner (German-American Club), L'Unione Italiana (Italian Club), La Union Martí-Maceo, Circulo Cubano (Cuban Club), El Centro Español, and El Centro Asturiano. These clubs started in Ybor City's early days. Centro Español was first, in 1891. They were places where new immigrants could find support and community. Over time, they offered more social and entertainment activities.

These clubs were founded by immigrants for immigrants. Money to build their large clubhouses came from member dues. Members usually paid about 5% of their salary.

The main reason for the clubs was to provide basic medical care. Medical care at the clubs' clinics was included in the weekly dues. Two clubs, El Centro Asturiano and El Centro Español, even built hospitals. Before medical insurance was common, this was a huge benefit.

Besides medical care, the clubs offered many social activities. Their buildings had gyms, small cafes for members, and large halls for concerts and plays. They also organized dances and picnics. Sometimes they rented buses for trips to places like Clearwater Beach. An active club filled a family's social calendar. They acted like extended families for generations of Ybor City residents.

The clubs were usually for people from specific backgrounds. The Italian Club was for Italians, El Centro Español for Spaniards, and so on. There were two main clubs for Cubans. Also, a club for northern Spaniards, El Centro Asturiano, formed separately.

Ybor City was in the American Deep South during the time of Jim Crow laws. These laws required people of different skin colors not to socialize publicly. So, the clubs had to follow these rules.

Because of these laws, the Cuban community had two main clubs. La Union Martí-Maceo was for darker-skinned Cubans. Circulo Cubano was for those with lighter skin. Cuban families often had members with different skin tones. This sometimes meant family members had to join different clubs. The Martí-Maceo club building was later torn down during the Urban Renewal program.

El Centro Asturiano was started by immigrants from Asturias, a region in northern Spain. They split from Centro Español. Unlike other clubs, it soon allowed all people of Latin descent to join. Because of this and its respected hospital, it often had the most members.

El Lector: The Factory Reader

One special tradition in cigar factories was El Lector (The Reader). Rolling cigars all day could be boring. So, workers wanted something to listen to. A lector sat on a raised platform in the factory and read aloud.

The lector usually started the day reading local Spanish newspapers. Then, they might read a fiction book, like a romance or adventure story. Since most residents were interested in politics, the lector would often read about current events in Cuba or Spain. In the afternoon, they might read a classic novel, like Don Quixote. Even workers who couldn't read learned about literature and world events.

Lectors were highly respected and often well-educated. Most could read English or Italian text and speak it aloud in Spanish. The workers, not the factory owners, hired and fired the lectors. Workers paid their salary with a small deduction from their weekly earnings. Workers loved this tradition and kept it going.

Most factory owners didn't like the lectors. They thought lectors stirred up workers with "radical ideas." Lectors sometimes shared news about labor problems elsewhere. This led to worker strikes and protests. Owners tried to ban lectors, but workers fought hard to keep them.

Lectors stayed in Tampa's cigar factories until 1921. Some owners made workers agree to remove lectors to end a strike. In 1931, after a very difficult strike, all Ybor City cigar workers had to agree to remove lectors.

Some lectors found other ways to share information. Victoriano Manteiga started La Gaceta, a newspaper in English, Spanish, and Italian. It's still published today by his grandson. Some lectors became teachers or cigar workers themselves. Others went to Cuba, where lectors were still allowed in factories.

Decline of Ybor City

The Great Depression's Impact

The Great Depression in the 1930s greatly hurt Ybor City. People bought fewer cigars because they were expensive. Many switched to cheaper cigarettes. This weakened the cigar industry, and the area slowly declined.

Many businesses closed, and banks failed. To get food, many residents planted vegetables in their yards. They also bought cows, goats, and chickens for milk, eggs, and meat. Any extra food was sold. The descendants of those chickens still roam the area today.

Ybor City and the Spanish Civil War

During the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), Ybor City was very active. The cry of "No pasaran!" (They shall not pass!) energized the community. They strongly supported the democratic government of Spain against General Franco's uprising. Many residents donated 10% of their salary and old clothes to the cause. Ybor City had the second-largest group of pro-Republican Spanish speakers in the U.S. A cigar worker even turned the slogan into a song.

News of Franco's victory in 1939 was very sad for Ybor City. It also cut many ties between Spanish residents and their families in Spain. Some relatives had been killed. Others couldn't communicate due to Franco's control and World War II. These links to the home country grew weaker.

After World War II

After World War II, Ybor City's decline sped up. Veterans returning home found few jobs and poor housing. Many moved away.

Demand for cigars didn't return to old levels. By 1945, the cigar industry employed less than half the workers it had in 1935. Factories also started using machines more. This meant fewer workers were needed, and they were paid less. Even when cigar demand grew after the war, machines meant fewer jobs. Tampa's economy grew with shipping and tourism, but Ybor City didn't get new industries.

Another problem was the old housing. New homes hadn't been built during the Depression or the war. Thousands of homes from around 1900 were old and falling apart. Returning veterans wanted newer homes. The Veterans Administration offered loans for new homes. Since Ybor City had few new homes, veterans looked elsewhere.

Also, the G.I. Bill helped many Ybor City veterans go to college. They started careers outside the cigar industry. Few could find suitable jobs in their old neighborhood. So, they moved away. The WWII generation was the first to leave Ybor City in large numbers.

Urban Renewal and Interstate 4

From the late 1950s to the early 1970s, Ybor City struggled. Its cigar industry kept shrinking. Its population moved to other parts of Tampa.

The Federal Urban Renewal Program in the 1960s aimed to fix up Ybor City. It planned new homes and businesses to attract tourists. Thousands of residents were forced to move. Whole blocks of old homes and factories were torn down. But due to lack of money, the new buildings were never built. Old buildings were replaced by empty lots.

The construction of Interstate 4 was another blow. It cut through the middle of the neighborhood. This tore down more homes and cut off many north-south roads.

Cuban Embargo's Impact

Ybor City's cigar industry was already declining. But in February 1962, things got worse. The U.S. put an embargo on all imports from Cuba, including tobacco. This meant no more "Havana clear" tobacco leaves. Many cigar factories closed. This further damaged Ybor City's economy. The neighborhood became full of empty factories and deserted streets.

Decline of the Social Clubs

As Ybor City emptied in the 1950s and 1960s, membership in the mutual aid societies declined. The clubs offered fewer services. Today, most focus on preserving their history and buildings.

The German-American Club closed before World War II. El Centro Español stopped most operations in the late 1980s. Its building is now part of the Centro Ybor shopping complex. The original Marti-Maceo Club building was torn down in 1965. The club is now in a former firehouse.

The remaining clubs, like the Cuban Club, Centro Asturiano, and Italian Club, have restored their buildings. They use dues, fundraisers, and rental fees to do this.

Empty Lots, Failed Plans

By the late 1960s, Ybor City's cigar industry was collapsing. Local leaders tried to find ways to bring the neighborhood back to life. There were ideas to turn empty land into homes, shops, or tourist spots. One mayor suggested digging canals and bringing in gondolas to create a "Venice, Italy" attraction. Another idea was a "Old Spain" theme park with "bloodless" bullfighting. An exhibition bull escaped and had to be killed. None of these ideas happened due to lack of money.

By the early 1970s, very few businesses and residents remained in Ybor City's main commercial area. The Columbia Restaurant was one of the few left. The northern part of the neighborhood, separated by I-4, still had people. But it changed from a middle-class Latino area to one with more working poor and African American residents. Urban Renewal didn't touch northern Ybor City. Many residents lived in old homes built for immigrants.

Ybor City's Comeback

In the late 1980s, artists started moving into Ybor City. They turned empty storefronts on 7th Avenue into studios and galleries. This began a period of renewal for the area.

By the early 1990s, many old brick buildings on 7th Avenue became bars, restaurants, and nightclubs. Crowds grew, especially on weekends. The city built parking garages and closed 7th Avenue to traffic.

While this was good, some people worried about the noise and traffic. Since 2000, Tampa has encouraged more diverse development. A family-friendly shopping complex and movie theater, Centro Ybor, opened in the old Centro Español club. New apartments, condos, and hotels have been built. People are moving back to the area around 7th Avenue for the first time in many years. In 2009, IKEA opened Florida's largest store just north of the Selmon Expressway.

The comeback hasn't reached all parts of Ybor City equally. Areas north of I-4 and east of 22nd Street still have problems with poverty. Many residents there still live in old cigar workers' homes.

From 2000 to 2009, the V.M. Ybor neighborhood, north and west of the historic district, also started to improve. Poverty rates in this area dropped significantly.

Most of Tampa's cigar factories were made of wood. By 2018, only two wooden structures remained. The Oliva factory was renovated into apartments. The Salvador Rodriguez Co. building is now an office.

In July 2018, the Tampa Bay Rays baseball team announced plans for a new stadium in Ybor City. But in December 2018, they decided the location wasn't right.

As of 2023, one cigar factory still operates in Ybor City. The J. C. Newman Cigar Company moved to Tampa in 1954. They still use some antique, hand-operated cigar-making machines from the 1930s.

The local museum is the Ybor City Museum State Park. It's in the old Ferlita Bakery building on 9th Avenue. You can take tours of the gardens and the "casitas" (small homes of cigar workers). The museum has exhibits, old photos, and a video about Ybor City's founding and cigar making.

Images for kids

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |