History of pharmacy in the United States facts for kids

The history of pharmacy in the United States tells the story of how new ideas about medicines came together. It mixes advancements from Europe, Native American medicine, and new plants found in the New World. American pharmacy grew from these different influences and has shaped both U.S. history and the global story of pharmacy.

An apothecary was an old name for someone who prepared and sold medicines. In earlier times, apothecaries did more than just give out medicines; they also suggested remedies and even gave some treatments. In the U.S., since the mid-1800s, most apothecaries have been called "pharmacists." This change happened to help make the field more organized.

Unlike in the UK, where pharmacists and apothecaries became separate jobs, in the U.S., these roles often overlapped. The term "apothecary" is still sometimes used, along with "druggist," but "pharmacist" is the main title today. As pharmacy became a clear and defined profession, American pharmacists made their own discoveries. They played a big part in the medical changes of the 1800s and 1900s, helping to create modern medicine.

Contents

Colonial period: Early Steps in Pharmacy

Finding New Medicines

When Columbus began exploring the Americas in the late 1400s, Europeans started looking for valuable medicinal plants. They wanted to add these new plants to their medical knowledge. Some early medicines found in the New World included guaiacum (for coughs), sassafras, copaiba, Peru balsam, and most famously, cinchona bark from Peru. Cinchona bark, also called "Jesuit's bark," was the first effective treatment for malaria. Its active ingredient, quinine, was the main treatment for malaria until the 1940s.

Many plants used by Native Americans became important in the U.S. About 170 drugs from Native Americans in British North America and 50 from indigenous people in other parts of the Americas were listed in the United States Pharmacopoeia (started in 1820). This book lists official medicines and their uses.

In the early 1700s, James Oglethorpe, who founded the Georgia colony, tried to find and grow useful plants from tropical colonies in Savannah, Georgia. He had financial help from the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London. However, this effort did not succeed. The main researcher got sick, and support from London stopped when he died.

Pharmacy in the 1700s in North America

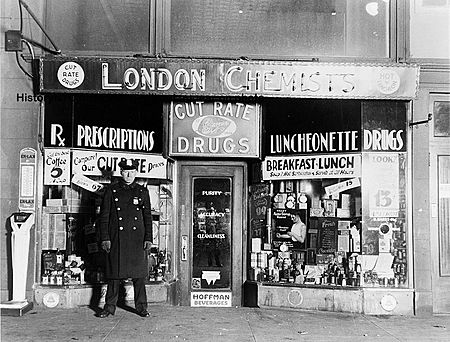

The first "drugstores" in North America appeared in places like Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Before these dedicated shops, some general stores sold drugs. Like the first apothecary shops in the medieval Arab world, many drugstores continued to sell general goods, perfumes, cosmetics, and drinks alongside medicines. Many still do this today.

Non-British Influences on Pharmacy

The Spanish were the first in North America to license a pharmacist in 1769 in New Orleans. They were also the first to regulate pharmacy as a separate job. This shows how important non-British governments and settlers from Europe were. They brought more modern pharmacy methods and rules from Europe to the young United States.

In "Franco-Spanish" Louisiana, pharmacy developed more like it did in Continental Europe. A key moment happened on February 12, 1770. The governor in New Orleans, Don Alexandre O'Reilly, issued a rule that defined the roles of medicine, surgery, and pharmacy. This was the first time pharmacy was legally recognized as its own field in the areas that would become the United States. Even though only a few pharmacists were licensed under this system, O'Reilly's rule set an important example for the future.

Jesuit-trained apothecaries also had a big impact in New Spain and New France. Jesuits were very involved in caring for the sick in their missions. They helped translate Native American ethnobotany (knowledge of plants) into medicines that Europeans could use.

Pharmacy in British North America

Before pharmacy became organized in the U.S. (around 1821), it was very disorganized. People often sold medicines by hawking them, and there were no rules to protect the public from fake or harmful products. Many "fakirs and charlatans" tricked people into buying their "fantastic panaceas" (cure-alls). In Europe, organized pharmacy had existed for two or three centuries, but in the U.S., it started later with the founding of the first formal college of pharmacy in 1821.

In the early British colonies, pharmacy was more informal. There were almost no rules about who could practice pharmacy or where. The roles of pharmacist, wholesale druggist, and doctor often overlapped. Doctors usually prepared and gave out their own medicines because they were paid for the medicine, not just the visit. So, often the doctor was also the apothecary, especially in rural areas. Even in the 1760s, many famous American doctors ran their own medicine businesses, mixing and dispensing medicines by hand. They also used "patent medicines" imported from the UK or Europe.

In cities, commercial pharmacy slowly grew. By 1721, Boston had 14 apothecary shops. The first official pharmaceutical officer in an American army was Andrew Craigie, an apothecary from Boston. He fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775. In 1777, Craigie became the first Apothecary General for the army.

Important early American apothecary shops include one in colonial Fredericksburg run by Hugh Mercer, who later became a general in the Continental Army. The Marshall Apothecary in Philadelphia (started 1729) made and sold medicines and was a key supplier during the Revolutionary War. By the end of the 1700s, advertisements show that most American cities had drugstores.

By the end of the 18th century, medical professions had changed a lot. Better medical education, new science, and a growing middle class led to more professional feelings. Apothecaries, who were once seen as just tradesmen, became practicing doctors who could write prescriptions and treat patients directly. In remote areas, the apothecary was often the only doctor.

A "pharmacopoeia" is a book that lists useful drugs. It also sometimes removes questionable substances. These books became very important in the early modern age (1500s to late 1700s). But pharmacopoeias mainly gave basic information and instructions for mixing medicines.

Later, "dispensatories" were published. These books gave more complete information about medicines, including how and when to use them and best practices. British dispensatories were especially important in the late 1600s and 1700s. William Lewis' The New Dispensatory (1753) was considered the first truly scientific pharmacy book in English. Another important book was the Edinburgh New Dispensatory (1786). These books were printed many times and in many languages, including six times for use in America.

The 19th century: American Pharmacy Grows

The 1800s saw the birth of "pharmacy as we know it." Developments in Europe continued to help pharmacy grow in the young United States.

The Philadelphia College of Pharmacy: Organized Pharmacy Begins

The Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (PCP) was started in 1821. It was inspired by similar colleges in Paris and was helped by European experts. Elias Durand, a pharmacist who had worked for Napoleon I, opened a shop in Philadelphia in 1825. He brought new scientific ideas to American pharmacy. He shared new findings about medicinal plants, made new medicinal chemicals, and trained apprentices.

The founding of the PCP was a big step for pharmacy in the U.S. In 1821, a meeting of apothecaries was held in Carpenters' Hall (where the U.S. Declaration of Independence was signed). They created the first formal college of pharmacy and the first pharmacists' association in North America. Sixty-eight pharmacists signed the Constitution of this new association. The PCP's constitution included a strict code of ethics. It said that anyone who "adulterated" (made impure) medicines or knowingly sold bad products would be expelled. It also had committees to check medicine quality and settle disputes.

The PCP quickly made a big difference. In 1824, they published official formulas for making "secret-formula" patent medicines that used to be imported from the UK. This was a key step toward the U.S. making its own medicines.

The Philadelphia College of Pharmacy also helped create the American Pharmaceutical Association (APhA). This group formed at a meeting in the PCP's hall in October 1852. Daniel B. Smith, who was the PCP's president, became the APhA's first president.

The "Father of American Pharmacy"

William Procter, Jr. is known as the "Father of American Pharmacy." He graduated from and taught at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy for 20 years. Procter helped create a special teaching position for pharmacist-professors at the PCP in 1844. He then wrote "the first American pharmacy textbook," called Practical Pharmacy (1849). This book became a model for later popular books like Edward Parrish's An Introduction to Practical Pharmacy and Joseph P. Remington's Practice of Pharmacy.

Procter also led the American Journal of Pharmacy for 22 years and worked for 30 years on the U.S. Pharmacopeia committee, helping to improve it. He also became president of the American Pharmaceutical Association (APhA). At an international pharmacy meeting in Paris in 1867, Procter strongly argued against limiting the number of pharmacies in a city. He said that in the U.S., the public helps keep dishonest operators in check. This idea became known as "the American Way of Pharmacy."

Pharmacy Schools and Organizations Spread

Other big cities on the Eastern Seaboard followed Philadelphia's example. They started university training programs, professional groups, and colleges of pharmacy. New York City was one of the first, establishing the New York College of Pharmacy in 1829.

These pharmacy schools often acted like professional groups. They promoted pharmacist education and the idea of pharmacists as a distinct profession. They warned against "inferior druggists" and said the community should care about the training of those who provide medicines.

First Pharmacists on the West Coast

While modern pharmacy was developing on the East Coast in the early 1800s, it took several decades for it to reach the far southwestern parts of America. By 1850, Los Angeles had some doctors, but none had specific degrees in pharmacy. However, they often acted as "druggists."

One of the first doctors in Los Angeles, Dr. William B. Osborn, is credited with starting the first "drug-store" around 1854. He later sold his business to Dr. James P. McFarland and John Gately Downey. Downey had worked as a druggist in Ohio before coming to California. His main goal was politics, not pharmacy. He later became the seventh Governor of California (1860-1862).

It wasn't until around 1860 that the first two European-trained pharmacists arrived in Los Angeles. They were Theodore Wollweber and Adolph Junge, both from Germany. Junge's "drug store" was open for about 20 years. Dr. Joseph Kurtz, a future medical pioneer, arrived in Los Angeles in 1868 at Junge's suggestion. Kurtz became the first Los Angeles County Medical Examiner and helped found the Los Angeles County Medical Association. Junge's original prescription book can still be seen today at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

The USC College of Pharmacy was established in 1905. The retail pharmacy industry in Los Angeles grew significantly later. In 1919, the Borun brothers founded Borun Brothers, a drug wholesaler. Ten years later, in 1929, they opened their own retail stores called Thrifty Cut Rate, which later became Thrifty Drug Store. This started the modern chain-store model, with professional pharmacists working in-house. By 1942, they had 58 stores around Los Angeles, setting a business model for other large drug store chains.

Pharmacy and the Industrial Revolution

With new machines and mass production, new ways to deliver medicine became possible. These included the tablet (1884), the enteric-coated pill (1884), and the gelatin capsule (first made in large amounts in 1875). By 1900, most pharmacies sold medicines that were already made in factories by the growing pharmaceutical industry. This meant pharmacists did less of the traditional work of making medicines themselves.

This change worried many people. They were concerned about the quality of medicines and whether pharmacists would still be important. William Procter said that if a pharmacist only gives out medicines, "he relapses into a simple shopkeeper."

21st Century Developments in Pharmacy

Pharmacists as Healthcare Providers

At the start of the 21st century, there were concerns about a shortage of primary care doctors in the U.S. It was predicted that there would be tens of thousands fewer doctors than needed by the 2020s. Also, more people had health insurance and needed primary care. Many saw this as a chance to expand what other healthcare professionals, like pharmacists, could do.

On a national level, laws to recognize pharmacists as healthcare providers were first suggested in 2014. The goal was to change the Social Security Act to include pharmacists' services in medically underserved areas under Medicare Part B. This bill did not pass but was brought up again several times.

Many states are now expanding what pharmacists can do. Besides advanced practice roles, pharmacists in some settings can perform certain tasks under a collaborative practice agreement (CPA) with a doctor. These tasks include:

- Assessing patients by gathering information.

- Prescribing medications to manage diseases (starting, stopping, or changing treatment).

- Ordering lab tests and understanding the results.

- Working with other healthcare professionals to coordinate patient care.

- Building relationships with patients for ongoing care.

In 2019, the California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) set up billing codes for pharmacy services. This means pharmacists can bill for services like new patient visits, established patient visits, or giving immunizations.

Women in Pharmacy in the United States

Elizabeth Gooking Greenleaf was the first female apothecary in the Thirteen Colonies. She is considered the first female pharmacist in the United States.

Mary Corinna Putnam Jacobi was the first woman to graduate from a U.S. school of pharmacy in 1863, from the New York College of Pharmacy.

Susan Hayhurst was the first woman to receive a pharmacy degree in the United States in 1883.

Cora Dow (1868–1915) was a leading female pharmacist of her time in Cincinnati, Ohio. She owned eleven stores when she died.

Julia Pearl Hughes (1873-1950) was the first African-American female pharmacist to own and run her own drug store.

Anna Louise James (1886-1977) was the first African-American female pharmacist in Connecticut.

|

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |