History of street lighting in the United States facts for kids

The history of street lighting in the United States shows how cities have grown and changed. Street lights helped businesses stay open at night. They also played a big part in how America developed, especially with new ways to travel like cars. For over 250 years, before LED lights became popular, cities used oil, coal gas, carbon arc, incandescent, and special gas lamps to light their streets.

Contents

Early Street Lights: Oil Lamps

The very first street lights in America were oil lamps. They burned whale oil from large whales found in the Atlantic Ocean. People called Lamplighters had the job of lighting these lamps and keeping them working.

In the 1750s, inventor Benjamin Franklin from Philadelphia made oil lamps better. He designed them with two wicks to draw up more oil. He also used flat glass panes that were cheaper and easier to replace than blown glass bowls.

In Boston, a group of citizens led by John Hancock put up over 300 oil lamps from England in 1773. A newspaper had asked for public lamps to stop crime and keep people safe at night. These glass lamps were placed on ten-foot-tall posts, 50 feet apart, just like in London. These early lights were not very bright. People walked from one small pool of light to another, often through dark shadows.

By 1809, New York had more than 1,600 oil lamps for street lighting. The city started using sperm oil in 1792, which burned brighter than candles. Philadelphia was also busy, with 1,100 street lamps around this time.

Gas Street Lighting Arrives

Gas lamps slowly began to replace oil street lamps in the United States. This started in the early 1800s. The first street in the world lit by gas was Pall Mall in London in 1807. The first U.S. city to use gas street lights was Baltimore, starting in 1817.

In 1816, artist Rembrandt Peale showed how gas lamps could light up exhibits at the Peale Museum in Baltimore. People called it "the beautiful and most brilliant light." The next year, a company called the Gas Light Company of Baltimore was formed. The city allowed them to lay pipes to bring coal gas to light public streets.

Even though New York and Philadelphia tried gas lighting, they were slower to switch. They already had good oil lamp systems. By 1835, New York, Philadelphia, and Boston had built networks of pipes from gas plants. These supplied gas light to shopping areas, rich neighborhoods, and main roads. But in 1835, only 384 of New York City's 5,660 street lamps were gaslights. Chicago turned on its first gaslights on September 4, 1850.

Gas light was much brighter than oil lamps, up to ten times brighter. But by today's standards, they looked "distinctly yellow and not very bright." In 1841, a British writer named James Silk Buckingham said New York City's street lights were not good enough. He said it was "impossible to distinguish names or numbers on the doors" from a carriage or even walking. By 1893, New York City had 26,500 gas street lights but only 1,500 electric lights.

Electric Street Lighting: A Bright New Era

Arc Lamps: The First Electric Glow

The first public show of outdoor electric lighting in the U.S. happened in Cleveland, Ohio, on April 29, 1879. Inventor Charles F. Brush had made a special dynamo arc light. This lamp could shine as brightly as 4,000 candles. For the show, Brush put twelve 2,000-candlepower lamps on tall towers around Cleveland's Public Square. Thousands of people came to see the square lit up with electric light.

The city of Wabash, Indiana, was the first city to buy and install Brush's arc lighting system. On March 31, 1880, Wabash became "the first town in the world generally lighted by electricity." Four 3,000-candlepower Brush lights were hung from the flagstaff on top of the Wabash County Courthouse. They filled the area with light. An eyewitness said people were "overwhelmed with awe." A reporter said he could read a newspaper from a street away.

People quickly wanted the Brush street lighting system. It gave better light and cost one-third less than gas lamps. In 1880, Brush showed his lights in New York City. He put 23 arc lamps along Broadway. Brush then won contracts to light Union Square and Madison Square. On main roads like Broadway, arc lamps were placed on lampposts every 250 feet. By 1886, about 30 miles of roads in New York City had arc lamps. But on Fifth Avenue, arc lamps were taken down. Residents complained the wires looked "unsightly." Most of the street went back to the "gloom of gas." By 1893, New York City had 1,535 electric arc street lights.

In New Orleans, arc lamps were used for street lighting starting in 1881. By 1885, New Orleans had 655 arc lights. In Chicago, arc lamps were used for public street lighting starting in 1887. At first, they were only on Chicago River bridges. But by 1910, they were used more widely on major Chicago streets.

Incandescent Lights: A Warmer Glow

In the early 1900s, different types of street lighting competed with each other. These included carbon arc lamps, incandescent lamps, and traditional gas lamps. Incandescent lamps were first made for indoor use. But big technology improvements in 1907 and 1911 made them better for outdoor use. From 1911 on, electric incandescent lamps with special tungsten wires became very popular for public street lighting.

In 1919, San Francisco started using tungsten bulbs on Van Ness Avenue. They replaced gas lamps and arc lamps. The city used two 250-candlepower tungsten lamps on each pole. A magazine called The Electrical Review said that before, it was dangerous for people to cross the street because of car traffic. But with the new lights, "the entire street is flooded with evenly distributed light." By 1917, over 1.3 million incandescent lamps were used for street lighting across the U.S. The number of arc lamps had started to go down.

Mercury Vapor Lamps: More Efficient Lighting

By the mid-1900s, more cars meant streets needed to be lit better. This was especially true in business areas where cars and people mixed. Streets needed to be lit more evenly, and lights needed to stay on all night. Street lighting became very expensive for U.S. cities. Incandescent lamps were not very good at making visible light. This made them less and less appealing for public street lighting.

Mercury vapor streetlights started to be used more widely in the United States after 1950. They were more cost-efficient. By then, mercury vapor lamps could last up to 16,000 hours. They also produced more light for the energy they used. Incandescent lamps were not as good.

The first large use of mercury vapor lamps in the U.S. was in Denver, Colorado. In 1964, almost 39 percent of street lights in the U.S. were mercury vapor. Incandescent lamps made up 60 percent. By 1973, incandescent outdoor lamps were quickly disappearing, while mercury vapor lamps were being made much more.

Sodium Vapor Lamps: Yellow Light for Safety

Low-pressure sodium vapor street lights make a strong yellow light. This yellow light helps the human eye see more details, even when it's not very bright. In the 1930s, sodium vapor lamps were not efficient enough to be a good choice over incandescent lamps. But because they helped people see better, they were suggested for safety lighting in tunnels, on bridges, and at highway exits.

In the U.S., street lights using sodium vapor were first put up on a rural highway near Port Jervis, New York, in 1933. A study in 1938 said that using sodium vapor light at certain intersections in Chicago helped reduce accidents. Lamp makers started to say sodium vapor lamps could help "crime fighting." But this idea backfired. Cities like Newark and New Orleans said no to sodium vapor. They did not want to make high-crime areas stand out.

When high-pressure sodium vapor lamps became available in the mid-1960s, lamp makers again said they could help with street safety. High-pressure sodium lamps made a clear "yellow/orangeish light." This was brighter than mercury vapor light, which was described as a "harsh metallic blue." During the 1973 oil crisis, Mayor Richard J. Daley announced a plan for Chicago. He wanted it to be "the first large U.S. city to have sodium vapor lamps on all residential streets." This meant replacing 85,000 mercury vapor streetlights. A newspaper article in December 1973 was hopeful about the "more cheerful, brighter, gold-colored vapor lamps." But the newspaper's own architecture critic worried about the "eerie, ominous quality of sodium vapor illumination." In 1976, many sodium vapor lamps were installed on Chicago's main streets.

The biggest reason for using sodium vapor lamps was their cost. In 1980, an incandescent lamp cost $280 a year to run. A mercury vapor lamp cost $128. But low-pressure sodium vapor lamps cost only $60 a year. High-pressure sodium vapor lamps cost just $44 a year to run. They also lasted 15,000 hours, which saved money on repairs. The Edison Tech Center says sodium vapor lamps are "the most common lamp for street lighting on the planet."

Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs): The Future of Light

Recently, cities have focused on using light-emitting diodes (LEDs) to save energy. LEDs replace older high-pressure mercury, metal halide, and high-pressure sodium lamps. LEDs also make a whiter light. They can be part of a smart system that saves even more energy by dimming lights or turning them off part of the night.

Installing LED lights costs a lot at first. But cities expect to save money over time from lower electricity and maintenance costs. Many early projects in the U.S. also got help from government grants.

In 2007, Ann Arbor, Michigan, announced plans to be "the first US city to convert all of its downtown streetlights to LED technology." The city replaced 120-watt bulbs that lasted two years with 56-watt LEDs that would last ten years. They expected to cut their public lighting energy use in half. By January 2011, Ann Arbor had switched 1,400 of its 7,000 streetlights to LEDs. This saved about $200,000, including less money spent on repairs.

Other Ways to Light Streets

Lighting Towers: Giant Lamps for Cities

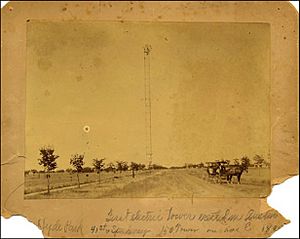

Many cities in the U.S. tried using tall towers to light up whole neighborhoods. This was like the arc lamp setup at the Wabash County Courthouse. In 1802, Benjamin Henfry put an oil-based lamp on a tall pole in Richmond, Virginia. But it didn't give off as much light as he hoped. In Washington, DC, city planners thought about using the Washington Monument as a lighting tower. But they decided against it after testing lamps on the Smithsonian Institution and U.S. Capitol buildings.

Cities that used tower lighting (or "moontowers") for a while included Akron, Austin, Buffalo, Denver, Detroit, and Los Angeles. Most of these cities only put up one or two towers. Then they went back to regular lamppost lighting. One exception was Los Angeles, which put up 36 towers. Fifteen of these were 150 feet tall and had three 3,000-candlepower arc lamps each. Another exception was Detroit, which tried to use 122 towers to light 21 square miles of the city. Even though Detroit's towers provided "uniform carpets of light," they didn't light busy areas well enough. After five years, Detroit started taking its towers down.

As of October 2021, the only lighting towers left in the United States are in Austin, Texas. The city of Austin bought 31 of Detroit's used moonlight towers in 1894. Seventeen of those towers, put up in Austin in 1895, still work today.

Induction Lighting: Long-Lasting Light

In 2009, PSE&G in New Jersey became the first power company in the U.S. to use induction fluorescent lamps. They replaced mercury vapor lamps in 220 towns. These induction lamps were expected to last 100,000 hours before needing repairs. They also use 30 to 40 percent less electricity, saving about $1 million each year. Induction lamps also give a whiter light and have less mercury.

After many tests, the City of San Diego decided in 2010 to replace 10,000 of its high-pressure sodium streetlights with induction lamps. Astronomers from the nearby Palomar Observatory were worried about new lights that would cause more light pollution. This could interfere with their research. One important finding was that LED lights became more expensive and less efficient at lower color temperatures. The City of San Diego now uses induction lighting for street lights. But they use low-pressure sodium lamps within 30 miles of the observatory to protect the night sky for stargazing.

Urban Light: Art from Street Lights

Urban Light is a famous art piece at the entrance to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). It is made up of historical street lights that were actually used in Southern California. Artist Chris Burden created this sculpture in 2008.

|

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |