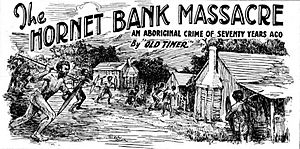

Hornet Bank massacre facts for kids

The Hornet Bank massacre was a terrible event where eleven settlers and one Aboriginal station-hand were killed by a group of Iman Aboriginal Australians. This happened very early in the morning on October 27, 1857, at Hornet Bank station. The station was located on the upper Dawson River near Eurombah in central Queensland, Australia. After this event, many Aboriginal people died in revenge attacks. These attacks were carried out by the Native Police, groups of settlers, and William Fraser. Some estimates say around 150 Aboriginal people died in the Eurombah area. Other reports suggest over 300 Aboriginal men, women, and children were killed in the Wide Bay area alone. For a long time, it was thought that the entire Iman tribe and language group had been wiped out by 1858. However, this idea has been challenged, and today, descendants of the Iman people are recognized as the traditional owners of the land around Taroom.

Contents

Why Did the Attack Happen?

European settlers, called squatters, started moving onto Iman land in 1847. This happened after Ludwig Leichhardt explored the area in 1844-45. He was looking for a route to Port Essington in northern Australia.

Hornet Bank station was the furthest west that Europeans had settled in the area. Andrew Scott set up the station in the early 1850s. In 1854, he rented it to John Fraser, who was from Scotland. John Fraser moved there with his wife, Martha, and their many children, who ranged from toddlers to young adults. This area was very far from other European settlements. Two years later, John Fraser died from an illness while on a trip to Ipswich. His oldest son, William, who was 23, then took over running the station with Andrew Scott.

The stations along the Dawson River were on the land of the Iman people. The Iman were very upset about these European settlers moving in without asking or negotiating. The Europeans brought sheep and cattle, which the Iman saw as a problem for their land. The settlers often treated the Iman people badly, which made the Iman feel even more unfairly treated. They were also stopped from using their own land. This made the surrounding country dangerous for the European settlers. Shepherds in small huts were attacked and killed, and others worried about leaving their families unprotected. Some reports from that time said the Iman were very violent and that the Fraser family had always been kind to them. However, it has also been suggested that the attack on the Frasers was revenge. This revenge was for 12 Iman people who had recently been shot for spearing cattle. It was also possibly for an unknown number of Iman who had died nine months earlier after eating a Christmas pudding that was said to have poison in it, possibly given by the Fraser family.

The Iman Attack on Hornet Bank

The Iman attacked the Fraser home between one and two o'clock in the morning on October 27, 1857. Inside the house were Martha Fraser, eight of her nine children, their teacher Henry Neagle, two white station workers who lived in a hut about 1 kilometer away, and Jimmy, an Aboriginal servant. The night before the attack, Jimmy was convinced to help and killed all the station dogs. It seems the Iman first planned to kidnap one of the Fraser women. But things got out of control after the first Fraser family member who faced them was killed. The attackers ended up killing almost everyone at the homestead.

The only person who survived was fourteen-year-old Sylvester "West" Fraser. He was hit on the head with a waddy (a wooden club) and fell between the wall and a bed. The Aboriginal attackers were then distracted when the two station workers arrived. This allowed Sylvester to crawl under his mattress and stay hidden. Sylvester later ran about 19 kilometers to a nearby station called Cardin. He ran "without hat or boots and in a terribly bruised state" to get help. The workers there quickly formed a group and found a large number of Aboriginal people sleeping about 16 kilometers from the Fraser property. They "showed them no mercy," meaning they attacked them.

Who Was Killed?

The victims were buried on the property.

- Martha Fraser, 43 years old

- John Fraser, 23 years old

- Elizabeth Fraser, 19 years old

- David Fraser, 16 years old

- Mary Fraser, 11 years old

- Jane Fraser, 9 years old

- James Fraser, 6 years old

- Charlotte Fraser, 3 years old

- Henry Neagle (teacher), 27 years old

- R. Newman (shepherd), 30 years old

- Ben Munro (shepherd), 45 years old

- Jimmy (Indigenous houseboy)

Revenge Attacks and More Conflict

The Native Police's Role

During the European settlement of Australia, the main group that stopped Indigenous people from resisting was the Native Police. This police force was paid by the government. It had white officers in charge of Aboriginal troopers who came from different areas. The Native Police would "disperse" Indigenous resistance. This meant they would shoot and kill Indigenous men, women, and children they found in areas where settlers were moving in.

After the Hornet Bank massacre, Lieutenant Walter Powell and his Native Police division arrived first. They went west and found a group of Aboriginal people, killing five of them. Powell then made the surviving Fraser brothers, William and Sylvester, special police officers for his next mission. They shot and killed nine more people. Soon after, 2nd-Lieutenants Moorhead and Carr of the Native Police arrived with their troopers, killing about thirteen more Aboriginal people. By December 1857, Powell had more troopers. He used them to raid peaceful "station blacks" (Aboriginal people living on stations) at Taroom, killing five, including three women, as they tried to escape. Powell, along with William Fraser and 2nd-Lieutenant R.G.Walker, led another raid at Juandah, shooting eleven more Aboriginal people. By April 1858, other Native Police divisions were active in the area. They were led by Edric Norfolk Vaux Morisset, John Murray, John O'Connell Bligh, George Murray, and Charles Phibbs. These groups carried out many attacks. Henry Gregory and his brother, the explorer A.C. Gregory, who were also settlers in the area, joined these revenge missions. A local settler named George Serocold wrote that about a dozen local Aboriginal leaders were rounded up. They were told to run across an open field, and as they ran, they were shot and killed.

In June 1858, the New South Wales Legislative Assembly (a government group) started an investigation. They wanted to understand the killings on the Dawson River and make the Native Police force work better. The report was given on August 3, 1858. It did not suggest adding a group of armed settlers to the Native Police.

The "Browns" Group

George Serocold also helped create a group of armed settlers who wanted revenge after the Hornet Bank massacre. This group was called "The Browns." It included Serocold, his property manager at Cockatoo station, Murray-Prior, Horton, Alfred Thomas, McArthur, Piggott, Ernest Davies, and three Aboriginal servants, including Billy Hayes and Freddy. This group started at Hawkwood station. For six weeks, they carried out shooting attacks on mostly innocent "station blacks" in the area. They also committed a massacre at Redbank station. Three weeks later, the Native Police also went through Redbank station and carried out another massacre there.

Frederick Walker's Private Group

Even though the government's Native Police carried out many severe punishments, Aboriginal resistance in the area continued. Six station workers were killed in April 1858. Local settlers decided to add to the official Native Police. They paid for their own group of armed Aboriginal troopers. This group was led by Frederick Walker, who used to be a Native Police Commandant but was fired in 1854. Walker hired Aboriginal troopers who had left the Native Police. He led revenge patrols for the local landowners, going as far as Roma.

William Fraser's Revenge

William Fraser was the most determined avenger. He was in Ipswich when the massacre happened. His brother Sylvester rode to Ipswich to tell him. The two brothers returned to Hornet Bank, covering about 515 kilometers in three days by changing horses three times. William Fraser was allowed to ride with the Native police. This gave him "every opportunity to assuage his grief through murder." He continued killing Aboriginal people randomly wherever he found them. He shot an Aboriginal jockey at the racetrack in Taroom. After two Aboriginal people accused of being involved in the massacre were found not guilty, he shot both of them dead as they left the Rockhampton courthouse. It was reported that Fraser shot an Aboriginal woman in the main street of Toowoomba. He claimed she was wearing his mother's dress. Two policemen spoke with him briefly, then saluted him and walked away. This event made people believe that the government had given Fraser twelve months where he could not be charged with crimes, allowing him to get revenge for his family's massacre. In 1905, Fraser was asked if he had such permission. He replied, "I never asked and never received such an authority but felt I was justified in doing so (the killings)."

Near Wandoan, on the banks of the Juandah lagoon, there is a place called Fraser's Revenge. Local settlers say that a group of Aboriginal people massacred by Fraser's group are buried there. Also at Wandoan, Frederick Walker reported another incident to the attorney general in Brisbane. This involved the massacre of Aboriginal people at the magistrate's home in that town. These Aboriginal people had been found not guilty of involvement at Hornet Bank, but local white settlers shot them dead and buried them nearby.

On March 6, 1867, Fraser became an officer in the Native Police. He was sent to the barracks at Nebo, where he continued his campaign against Indigenous people. It was reported that in 1867, ten years after the massacre, Sub-Inspector William Fraser and his troopers were tracking a small group of Iman women and children. They had found safety at Mackenzie Station on the Fitzroy River. Mrs. Mackenzie was told Fraser was coming, so she hid the Aboriginal people in her bedroom. Fraser demanded to search the house and did so. But Mrs. Mackenzie stood in front of the bedroom door and refused to let him search that room. Fraser left without finding them after Mrs. Mackenzie strongly told him off.

William Fraser likely killed over 100 members of the tribe. This makes him one of the most deadly mass murderers in Australian history. Many more were killed by settlers who supported him and by the officers and troopers of the Native Police. An article about the massacre said that settlers just mentioning Fraser's name was enough to avoid trouble when they faced "truculent natives" (meaning difficult or aggressive Aboriginal people).

What Happened Afterwards?

It is not clear how many people died as a result of the Iman seeking their own revenge. But very few Iman people survived. Some managed to escape to Maryborough (about 300 kilometers east of Taroom). But even there, they were not safe. The police continued to bother them for several years afterward. Fraser's revenge campaign was thought to have led to the complete destruction of the Iman tribe and language. However, this is certainly not true, as some Iman men, women, and children escaped and hid further away than any police officers searched. By March 1858, up to 300 members of the tribe had been killed. Although the Iman people survived, not many actually live within the tribe's traditional lands. They are more commonly found in surrounding areas like Rockhampton, Mount Morgan, Gladstone, Blackwater, and many other towns both near and far. Public and police support for Fraser was so strong that he was never arrested for any of the killings. He became known as a folk hero throughout Queensland.

Sylvester Fraser never fully recovered, either physically or mentally. He continued to have fits, during which "blacks fled from him in alarm," even though he was harmless. It was reported that he died a broken man.

William Fraser died at 83 years old in Mitchell, Queensland on November 1, 1914. His obituary (a notice of his death) mentioned that he left behind two sons and 14 daughters. It also stated, "Any blacks that crossed Fraser's path for many years after [the massacre] got a particularly bad time; in fact, the name of Fraser was quite sufficient to strike fear and terror into their hearts."

In October 1957, to remember 100 years since the killings, a concrete memorial was put up at the grave site by Andrew Scott's descendants.

On September 18, 2008, the grave site and memorial were added to the Queensland Heritage Register. This means they are protected as important historical places.

See also

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |