Idaho v. United States facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Idaho v. United States |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued April 23, 2001 Decided June 18, 2001 |

|

| Full case name | Idaho v. United States |

| Docket nos. | 00-189 |

| Citations | 533 U.S. 262 (more)

121 S. Ct. 2135; 150 L. Ed. 2d 326; 2001 U.S. LEXIS 4665

|

| Prior history | United States v. Idaho (In re Coeur d'Alene Lake), 95 F. Supp. 2d 1094, 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22906 (D. Idaho 1998); United States v. Coeur d'Alene Tribe, 210 F.3d 1067, 2000 U.S. App. LEXIS 8583 (9th Cir. 2000) |

| Holding | |

| The United States, not the state of Idaho, held title to lands submerged under Lake Coeur d'Alene, and that the land was held in trust for the Coeur d'Alene Tribe. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Souter, joined by Stevens, O'Connor, Ginsburg, Breyer |

| Dissent | Rehnquist, joined by Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas |

Idaho v. United States was an important case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2001. The main question was who owned the land under Lake Coeur d'Alene and the St. Joe River in Idaho. The Court decided that the United States government, not the state of Idaho, owned these lands.

The Court also said that the United States held this land "in trust" for the Coeur d'Alene Tribe. This meant the land was kept safe for the tribe. This decision recognized how important these areas were for the tribe's traditional way of life, including getting food and other supplies.

Contents

A Look Back: The Coeur d'Alene Tribe's History

Early Days and Land Agreements

The Coeur d'Alene Tribe is a group of Native American people. They live in northern Idaho. Long ago, the Coeur d'Alene people lived on a huge area of land. This land covered about 3.5 million acres (1.4 million hectares). It stretched across parts of Idaho, Washington, and Montana. Today, the tribe's land is much smaller. It is called the Coeur d'Alene Reservation. It is located in Benewah and Kootenai counties in Idaho.

In 1853, Isaac Stevens was the governor of the Washington Territory. This territory included what is now the Idaho panhandle. Governor Stevens started making agreements, called treaties, with local tribes. By 1855, he had treaties with most tribes, but not with the Coeur d'Alene. Around this time, gold was found near Fort Colvile. Miners started entering tribal lands. This led to fighting between the tribes and the miners.

In 1858, a U.S. Army group led by Colonel Steptoe moved towards Coeur d'Alene lands. They met about 600 Native American warriors. After a fight, Steptoe's group had to retreat because they were running out of supplies.

Creating the Reservation and Lake Ownership

In 1867, President Andrew Johnson set up a reservation for the Coeur d'Alene tribe. The territorial governor had asked for this. However, the tribe did not accept this reservation. It did not include Lake Coeur d'Alene and the main rivers. These waterways were vital for the tribe's fishing and other needs. They used the rivers and lake for fish, plants like camas, and reeds for baskets.

In 1873, the U.S. government tried again. They sent a group to talk with the Coeur d'Alenes. After discussions, a reservation of about 598,000 acres (242,000 hectares) was created. This new reservation included the Hangman Valley, the Coeur d'Alene River, the St. Joe River, and almost all of Lake Coeur d'Alene.

This agreement was put into action by a special order from the President. It was meant to be temporary until Congress approved it. The tribe was supposed to get paid for any land they gave up. Congress never fully approved this action. In 1887, the tribe and the government made another agreement. This agreement said the tribe would give up some land outside the reservation. But Lake Coeur d'Alene and its waters were still part of the reservation.

In 1889, the tribe gave back the northern part of the reservation to the government. This included a piece of Lake Coeur d'Alene. They received payment for this. What was unusual was that the reservation border was drawn right across the lake. Usually, borders followed the natural shoreline. The agreement said it would not be final until Congress approved it.

Before Congress approved these agreements, Idaho became a state. The law that made Idaho a state said that Idaho would not claim public lands or lands owned by tribes. In 1891, Congress finally approved the earlier agreements with the tribe. Later, in 1894, the tribe gave up a one-mile-wide strip of land. This was for the Washington and Idaho Railway to build tracks. In 1908, Congress gave Idaho an area now known as Heyburn State Park.

Mining and Environmental Concerns

The Coeur d'Alene area was famous for mining. It was known as "Silver Valley." For many years, it was one of the biggest silver-producing areas in the country. From 1880 to 1980, a lot of silver, lead, and zinc were mined there.

However, this mining created a huge amount of waste. About 72 million tons of waste contaminated the land and rivers. This included the Coeur d'Alene River and Lake Coeur d'Alene. By 2012, the Silver Valley was the second-largest Superfund cleanup site in the U.S. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) named it this.

Previous Court Cases About the Lake

For many years, the Coeur d'Alene Tribe tried to work with Idaho. They wanted to clean up and manage Lake Coeur d'Alene. But they could not agree on how the tribe could have a bigger role. So, in 1991, the tribe decided to sue. They wanted to prove they owned the lake and the land under it.

The case first went to a U.S. District Court. This court first said the tribe could not sue the state directly. This was because of the Eleventh Amendment. This amendment generally protects states from being sued in federal court by citizens of other states or foreign countries. The tribe then appealed this decision.

The case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court. In that earlier case, called Idaho v. Coeur d'Alene Tribe of Idaho, the Court decided that the Eleventh Amendment did stop tribes from suing states directly. Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote the main opinion for the Court.

After this, the Coeur d'Alene Tribe asked the United States government to sue instead. They wanted the government to confirm its ownership of the submerged lands on the reservation. The tribe was allowed to join the government's side in this new lawsuit. The court decided that earlier agreements clearly meant to keep the lake and its submerged land for the tribe's use. So, the court ruled in favor of the United States.

Idaho appealed this decision. But the appeals court agreed with the first court's ruling. Idaho then appealed again to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

The Supreme Court's Decision

Arguments in Court

Lawyers for Idaho, the United States, and the Coeur d'Alene Tribe presented their arguments. Steven W. Strack argued for Idaho. David C. Frederick argued for the United States. Raymond C. Givens argued for the Coeur d'Alene Tribe.

The Court's Main Opinion

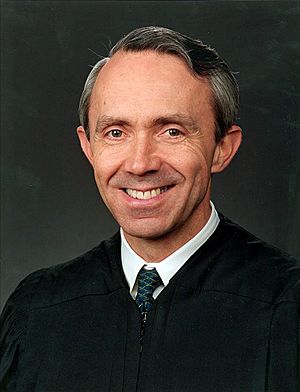

Justice David Souter wrote the main opinion for the Supreme Court. This decision was different from the earlier case. In this case, the Court said that even though states usually own submerged lands, it was clear that the United States had kept these lands for the Coeur d'Alene Tribe.

Justice Souter explained that the 1873 presidential order had included the submerged lands. He also pointed out that a report to Congress in 1888 showed that all submerged lands were held in trust for the tribe. Congress knew this when Idaho became a state. He also noted that the federal government had always treated with the tribe about these submerged lands. This included paying the tribe for the railroad's right-of-way.

Because of all this evidence, it was clear that the United States had kept the rights to the submerged land. This overcame the idea that the state should own it. The Court confirmed the earlier decision: the United States owned the land under Lake Coeur d'Alene.

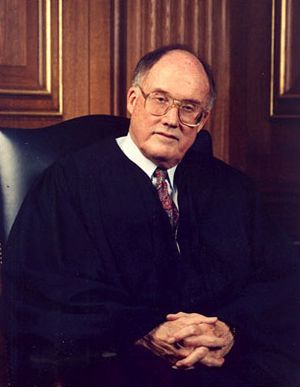

The Disagreement

Chief Justice William Rehnquist disagreed with the majority. He believed that once Idaho became a state, the ownership of the submerged lands automatically went to the state. He thought that what Congress did later, even if it was about agreements made before statehood, did not matter. He felt that only an action taken before Idaho became a state could have kept the tribal and federal ownership of the submerged lands. He would have sent the case back to a lower court to be decided differently.

What Happened Next

A year after the Supreme Court's decision, the Coeur d'Alene Tribe asked the EPA for permission. They wanted to set and enforce water quality standards under the Clean Water Act. This meant they wanted to help clean up the polluted lake.

Talks began between the state, the tribe, and the EPA. But they stopped because the state and EPA could not match the $5 million budget the tribe had for cleanup. In 2005, the EPA gave the tribe the authority they asked for. This allowed the tribe to regulate water standards, even for people who were not tribal members, to protect the tribe's health and well-being.

Later, the three groups came together again. After discussions, they agreed on a plan in 2009 to manage the lake. The tribe has also filed lawsuits against mining companies. They want these companies to help clean up the contaminated waters and land. Some politicians have tried to limit how much money the companies might have to pay for damages.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |