Imperial Wireless Chain facts for kids

The Imperial Wireless Chain was a special network of powerful long-distance radio stations. The British government built it to connect the different countries of the British Empire. These stations sent important messages, like business and government news, using Morse code. They used special machines that read messages from paper tape very quickly.

Even though people thought of this idea before World War I, the United Kingdom was one of the last big countries to build such a system. The first connection, between Leafield in England and Cairo, Egypt, opened on April 24, 1922. The very last connection, between Australia and Canada, started working on June 16, 1928.

Contents

Building the First Network

Guglielmo Marconi invented the first useful radio transmitters and receivers. Around 1900, radio started being used to talk between ships and land. Marconi's company, the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, was very important in early radio.

Before World War I, long-distance radio communication became very important for a country's defense. This was because an enemy could cut submarine telegraph cables, which would leave a country isolated. This actually happened during the war! So, around 1908, many industrial countries started building huge radio networks. These networks could send Morse code telegrams across oceans to their colonies.

In 1910, the Marconi Company suggested building a network of radio stations to link the British Empire. They said it could be done in three years. The government didn't accept the offer right away, but it made them think seriously about the idea.

Britain faced a problem: it already owned the biggest network of submarine telegraph cables. The new radio stations would compete directly with these cables. This could reduce the money the cable companies made and even cause them to go out of business.

The government decided that no single private company should have total control over this service. They also felt no government department was ready to build it. So, they decided to hire a commercial "wireless company." In March 1912, they signed a contract with Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company.

However, the government faced a lot of criticism. A special committee was set up to look into the matter. After hearing from important groups like the Navy and War Office, the committee agreed that an "Imperial wireless chain" was urgently needed. Experts also said that Marconi was the only company with technology proven to work reliably over long distances (more than 2,000 miles).

After more talks, a new contract was approved by Parliament on August 8, 1913. Many politicians voted for it, but many also voted against it. These events were also affected by the "Marconi scandal." This was when some important politicians were accused of using secret information about the contract to make money from Marconi shares. When World War I started, the government stopped the contract. Meanwhile, Germany successfully built its own radio network before the war. This network cost about two million pounds and helped them during the conflict.

After World War I

After the war ended, the Dominions (countries like Canada and Australia that were part of the British Empire) kept pushing the government for an "Imperial wireless system." In 1919, the House of Commons agreed to spend £170,000 to build the first two radio stations. These were in Oxfordshire (at Leafield) and Egypt (in Cairo). They were supposed to be finished in early 1920. However, the link actually opened on April 24, 1922, two months after the UK said Egypt was independent.

This decision came after Marconi sued the British government in June 1919. They claimed £7,182,000 because the government broke their 1912 contract. The court awarded Marconi £590,000. The government also asked a committee, led by Sir Henry Norman, to study the issue. This "Norman Committee" reported in 1920. It suggested that transmitters should reach 2,000 miles, needing relay stations. It also said Britain should connect to Canada, Australia, South Africa, Egypt, India, East Africa, Singapore, and Hong Kong. But this report wasn't acted upon.

While British politicians took their time, Marconi built stations for other countries. By 1922, they connected North and South America, as well as China and Japan. In January 1922, British business groups also demanded action. They said the Empire was losing a lot of money because the wireless chain wasn't built yet. Other groups, like the Empire Press Union, agreed.

Because of this pressure, after the 1922 General Election, the Conservative government formed another committee. This "Empire Wireless Committee" was led by Sir Robert Donald. Its job was to figure out the best way to set up an Imperial wireless service. The committee's report, given on February 23, 1924, had similar ideas to the Norman Committee. It said that any stations in the UK used for Empire communication should be owned by the state and run by the Post Office. It also suggested using eight powerful longwave stations and land-lines. This plan was estimated to cost £500,000.

At the time, the committee didn't know about Marconi's 1923 experiments with shortwave radio. Shortwave offered a much cheaper way to send messages than powerful longwave systems. It wasn't fully proven for business yet, though.

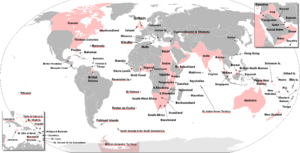

After the Donald Report and talks with the Dominions, they decided to finish the powerful Rugby longwave station. This station used proven technology. They also decided to build several shortwave "beam stations." These were called "beam stations" because a special directional antenna focused the radio signal into a narrow beam. These beam stations would connect with Dominions that chose the new shortwave technology. Finally, on August 1, 1924, Parliament approved an agreement. The Post Office and Marconi would build beam stations to talk with Canada, South Africa, India, and Australia.

Business Success

From when the Post Office started running the "Post Office Beam" services until March 31, 1929, they made £813,100. Their costs were £538,850, leaving a profit of £274,250.

Even before the last link between Australia and Canada opened, it was clear the Wireless Chain was very successful. This success was a problem for the cable telegraphy companies. So, a meeting called the "Imperial Wireless and Cable Conference" was held in London in January 1928. Delegates from the UK, the Dominions, India, and other parts of the Empire attended. They met to discuss how the new Imperial Beam Wireless Services were competing with the cable services. They wanted to find a common plan.

The conference decided that cable companies couldn't compete fairly in an open market. But, they also agreed that cable links were still important for business and defense. So, they suggested that the cable and wireless companies should merge. This would create one big company with a monopoly (meaning it would be the only one providing the service). This new company would be watched over by an Imperial Advisory Committee. It would also buy the government-owned cables and rent the beam stations for 25 years for £250,000 per year.

These suggestions became part of the Imperial Telegraphs Act 1929. This led to the creation of two new companies on April 8, 1929. One was an operating company called Imperial and International Communications. It was owned by a holding company called Cable & Wireless Limited. In 1934, Imperial and International Communications was renamed Cable & Wireless Limited. From April 1928, the Post Office operated the beam services for Imperial and International Communications Limited.

Changes in Ownership

The 1930s brought the Great Depression, which was a time of economic hardship. There was also new competition from the International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation and cheaper airmail. Because of these things, Cable and Wireless didn't make as much money as expected. This meant lower profits and they couldn't lower prices for customers as much as hoped.

To help with money problems, the British Government decided to give the beam stations to Cable and Wireless. In return, the government received 2,600,000 shares out of 30,000,000 shares in the company. This happened under the Imperial Telegraphs Act 1938.

The ownership of the beam stations changed again in 1947. The Labour Government took control of Cable and Wireless. Its UK assets were combined with those of the Post Office. By this time, three of the original stations had closed. Their services were moved to Dorchester and Somerton between 1939 and 1940. The longwave Rugby radio station stayed under Post Office ownership the whole time.

Beam Stations

The shortwave Imperial Wireless Chain "beam stations" worked in pairs. One station sent signals, and the other received them. The pairs of stations were located at (transmitters first):

- Tetney and Winthorpe (these connected with Ballan and Rockbank in Australia, and with Khadki and Daund in India)

- Ongar and Brentwood

- Dorchester and Somerton

- Bodmin and Bridgwater – the Bridgwater station was actually in a small village called Huntworth (these connected with Drummondville and Yamachiche in Canada, and with Kliphevel (now Klipheuwel) and Milnerton in South Africa)

At Bodmin and Bridgwater, each antenna was nearly half a mile (800 meters) long. It had a row of five tall lattice masts, each 277 feet high. These masts were placed 640 feet apart in a line, at a right angle to the overseas receiving station. On top of the masts were cross-arms, 10 feet high and 90 feet wide. From these cross-arms, vertical wires hung down, forming a "curtain antenna" (like a giant curtain of wires). At Tetney, the antenna for India was similar. The Australian antenna at Tetney was held up by three 275-foot-high masts.

The electronic parts for this system were made at Marconi's New Street wireless factory in Chelmsford.

Devizes was home to a receiving station until World War I began.

See also

- List of Marconi wireless stations

- History of radio

- Telecommunication

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |