Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Secretary of State and Superintendent of Public Instruction | |

| In office 1868 to 1872, 1873 to 1874 |

|

| Governor | Harrison Reed Ossian B. Hart |

| Preceded by | George J. Alden, Charles Beecher |

| Succeeded by | Samuel B. Mclin, William Watkin Hicks |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 28, 1821 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | August 14, 1874 (aged 52) Tallahassee, Florida |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Anna Amelia Harris, (divorced), and Elizabeth F. Gibbs |

| Relatives | Brother, Mifflin Wistar Gibbs; Niece, Ida Alexander Gibbs; Niece, Harriet Gibbs Marshall; Nephew-in-law, William Henry Hunt (diplomat) |

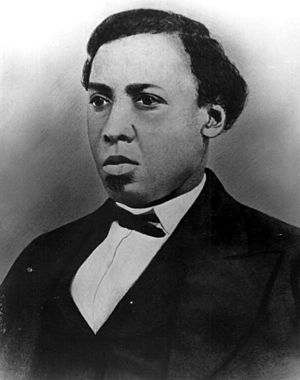

Jonathan Clarkson Gibbs, II (born September 28, 1821 – died August 14, 1874) was an important American Presbyterian minister. He also served as Secretary of State and Superintendent of Public Instruction for Florida. Along with Josiah Thomas Walls, Jonathan Gibbs was one of the most powerful African American leaders in Florida during the Reconstruction era. He was the first and only black Florida Secretary of State.

Contents

Jonathan Gibbs' Early Life and Education

Growing Up in Philadelphia

Jonathan Gibbs was born a free person in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on September 28, 1821. His father, Jonathan Gibbs I, was a Methodist minister. His mother, Maria Jackson, was a Baptist. Jonathan was the oldest of four children.

He grew up in Philadelphia when there were strong anti-black feelings. Many white people in the North at this time showed prejudice against black people. Jonathan and his brother, Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, went to the local Free School in Philadelphia.

After his father died in 1831, Jonathan and his brother left school. They needed to help their mother earn a living. Young Jonathan became a carpenter's apprentice. Both brothers later became Presbyterians. The Presbyterian church was so impressed with Gibbs that they helped him financially. This allowed him to attend Kimball Union Academy in Meriden, New Hampshire.

Studying in New Hampshire

Gibbs attended Kimball Union Academy (KUA) in Meriden, New Hampshire, and finished in 1848. The school's principal, Cyrus Smith Richards, was an abolitionist. An abolitionist is someone who wants to end slavery. At KUA, Gibbs met Charles Barrett, who became one of his closest friends.

Both Gibbs and Barrett later went to Dartmouth College. Dartmouth's president, Nathan Lord, had complicated views on slavery. However, he allowed several African Americans to attend the college. While at Dartmouth, Gibbs was influenced by three professors. He was also part of the abolitionist movement as a student. He spoke at several meetings.

Jonathan Gibbs was the third African American to graduate from Dartmouth College. He was also the second black man in the United States to give a graduation speech at a college.

Abolitionist Minister and Activist

Working for Change in New York

After graduating in 1852, Gibbs studied at Princeton Theological Seminary from 1853 to 1854. He could not finish his studies there because he ran out of money. He was ordained as a minister in 1856. He became a pastor at Liberty Street Presbyterian Church in Troy, New York.

Gibbs married Anna Amelia Harris, whose father was a wealthy black merchant in New York. They had three children: Thomas Van Renssalaer Gibbs, Julia Pennington Gibbs, and Josephine Haywood Gibbs.

After becoming a minister, Gibbs became very active in the abolitionist movement. He worked with famous leaders like Frederick Douglass. He became known across the country for his work. His growing involvement in the movement meant he was often away from home. This caused problems in his marriage, and he and Anna eventually divorced.

Returning to Philadelphia

Gibbs served as pastor of the First African Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia from 1859 to 1865. He was a key person in the Underground Railroad, which helped enslaved people escape to freedom. He also wrote articles for the Anglo-African Magazine.

When President Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation, Gibbs gave a sermon. He said that white people should get rid of their prejudices. He also said that black people should be allowed to fight in the Civil War. Gibbs asked, "Have white men of the North the same moral courage... to lay down their foolish prejudice... and place [the black man] in a position where he can bear his full share of the toils and dangers of this war?"

Along with William Still, Gibbs fought for equal treatment on public transportation in Philadelphia. They spoke out against separating people by race on the city's rail cars. Their efforts helped both free black people and those who were enslaved. As the Civil War ended, Gibbs left Philadelphia. He went South to help rebuild the former Confederate states. He also wanted to educate formerly enslaved people and poor white people.

Moving South to Help Others

In December 1864, Gibbs announced he was leaving his church in Philadelphia. He was invited to go South to help formerly enslaved people, known as Freedmen. This work became a project that lasted several years. Gibbs worked with other missionaries.

He arrived in New Bern, North Carolina. He wrote about the difficult conditions after the war. He said, "The destitution and suffering of this people extended my wildest dream." Gibbs eventually settled in Charleston, South Carolina. There, he started a local church and opened a school for children of Freedmen in 1865. This school was called Wallingford Academy.

Gibbs believed strongly in the power of education. He saw a connection between religious duties and helping the nearly four million newly freed people. He proudly told his friend Charles Barrett that he had a school in Charleston with an average of 1,000 children and about 20 teachers.

While in South Carolina, Gibbs also became involved in politics during Reconstruction. He attended a meeting of black delegates. They asked that educated people of both races be allowed to vote. They also said that if uneducated white men could vote, then uneducated black men should also be allowed to vote.

During this time, Gibbs met and married his second wife, Elizabeth. They had one child who died as a baby. Gibbs soon moved to Jacksonville, Florida and opened another school there.

A Leader in Florida Politics

Becoming Secretary of State

Gibbs moved to Florida in 1867 and started a private school in Jacksonville. He quickly became involved in Florida's Reconstruction politics. For black leaders during this time, religion and politics often went together.

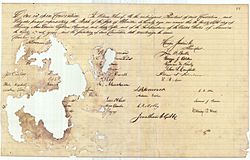

Gibbs was elected to the State Constitutional Convention of 1868. This convention created Florida's most liberal constitution up to that point. It also set up a system for public schools.

Even though Gibbs did not win an election to Congress, he was appointed Florida's Secretary of State. He served from 1868 to 1872. He was appointed by Republican governor Harrison Reed. Gibbs had a lot of power and responsibility in this role. He wrote to his friend Charles Barrett, saying he was "second man in the government of this State today."

Gibbs was very active as Secretary of State. He investigated violence and fraud, including the actions of the Ku Klux Klan. He also served on the Board of Canvassers, which checked election results.

Superintendent of Public Instruction

Gibbs served as Superintendent of Public Instruction from 1872 to 1874. In this role, he helped lead the state's education system. He was also made a lieutenant colonel in the Florida State Militia. In 1872, Gibbs was elected as a Tallahassee City Councilman. His son, Thomas Gibbs, later helped create the State Normal College for Colored Students in 1885. This college is now Florida A&M University.

Jonathan Gibbs' Death and Legacy

Jonathan Gibbs died on August 14, 1874, in Tallahassee, Florida. He reportedly died from a stroke. Some people rumored that he had been poisoned.

Gibbs was the brother of Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, a well-known judge in Arkansas during Reconstruction. He was also the father of Thomas Van Renssalaer Gibbs, who was a delegate to the 1886 Florida Constitutional Convention and a member of the Florida state legislature.

- Gibbs High School, the first high school for black students in St. Petersburg, is named after him.

- Gibbs Junior College (also in St. Petersburg) was named after him. This college later joined with St. Petersburg Junior College, which is now St. Petersburg College.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |