Julines Herring facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Julines Herring |

|

| Born | 1582 in Llanbrynmair, Wales |

|---|---|

| Died | 1644/5 in Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Nationality | English |

| Church | Church of England, Dutch Reformed Church |

| Education | Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge |

| Ordained | 1610 |

| Offices held | Preacher at Calke Lecturer at St Alkmund's Church, Shrewsbury Pastor at English Reformed Church, Amsterdam. |

| Spouse | Christian Gellibrand |

| Children | John, Jonathan, Samuel, James, Christian, Dorcas, Mary, Joanna |

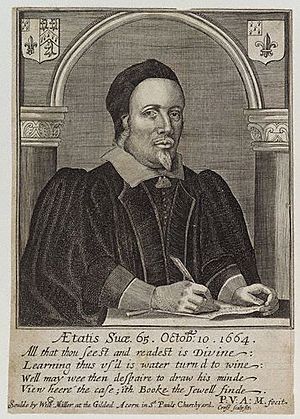

Julines Herring (1582–1644/5) was an English Puritan minister. Puritans were a group of Protestants who wanted to make the Church of England simpler. Herring worked in Derbyshire and Shrewsbury. He lost his jobs because he didn't follow all the church rules. Later, he moved to the Netherlands to serve English-speaking people there. He strongly believed in Presbyterianism, a church system run by elders. He was also against groups that wanted to completely separate from the main church.

Contents

Julines Herring's Early Life and Education

Julines Herring was born in 1582 in Llanbrynmair, Wales. His father, Richard Herring, was a well-known politician in Coventry, serving as mayor and sheriff. The family later moved back to Coventry.

School Days and Learning

Julines first went to school in a small village called More, Shropshire. There, he learned about religion from a relative of his mother, Mr. Perkin. He then attended the Free Grammar School in Coventry. Even as a student, he was known for being very religious. He loved reading the Bible and often prayed with his friends.

In 1600, Julines went to Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, a new Protestant university. He earned his first degree in 1604. After college, he returned to Coventry and studied Divinity (the study of religion). He was encouraged by Humphrey Fenn, a supporter of Presbyterianism. Herring soon started preaching and became very popular.

Starting His Ministry at Calke

To become a minister, Julines needed to be ordained. This meant taking an oath to accept the king's authority over the church and agree with the Book of Common Prayer. Julines and other young Puritans found an Irish bishop visiting London who would ordain them without requiring the full oath.

After this, Julines became a preacher at Calke in Derbyshire.

| Look up donative in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

He was recommended for this job by Arthur Hildersham, another Puritan preacher. Calke was a good place for Herring because it was a "donative." This meant the person who owned the land (the patron) could choose the minister without the local bishop's approval. This gave Herring more freedom to preach as he wished. The patron, Robert Bainbridge, was a strong Protestant who had even been jailed for his beliefs.

A Popular Preacher

Even though Calke was a small village, Herring's preaching attracted large crowds from many towns. People would travel far to hear him. They would often bring picnics and spend the whole day there. After the service, they would sing psalms and discuss his sermon on their way home. His powerful messages helped many people become strong Puritans.

Herring's time at Calke was stable. He married Christian Gellibrand, and they started a family. Their marriage was known for being very happy. He stayed at Calke until 1618. Some say he was forced to leave because he didn't conform to church rules. Others suggest he moved to a more important job in Shrewsbury.

Challenges in Shrewsbury

In 1618, Herring moved to Shrewsbury to become a lecturer at St Alkmund's Church. A lecturer was a preacher who gave sermons but wasn't in charge of the church. His salary was paid by Rowland Heylyn, a wealthy merchant who supported Puritan preachers.

Preaching and Opposition

Herring preached twice a week and repeated his Sunday sermon in private homes. His sermons were very popular. He taught that "all things are the true Christian's," meaning that everything belongs to those who truly follow God.

However, Herring faced challenges. In 1620, he was reported to the bishop, Thomas Morton, for not using the Book of Common Prayer and for how he handled church ceremonies. Bishop Morton was generally fair, and Herring was able to explain his views. But this incident led to times when he was suspended from preaching and then allowed back. Even when suspended, he continued to hold private prayer meetings at his home.

Opposition grew around Peter Studley, another minister in Shrewsbury. Studley complained that Herring's supporters held private meetings that were like illegal church gatherings. Herring also faced opposition from more radical groups, like Katherine Chidley, who wanted to separate completely from the Church of England. Herring disagreed with them, saying that separating from the church would cause many problems. He believed it was wrong to "unchurch a Nation at once."

A Strong Position in the Community

Herring remained a respected member of his local church, St Mary's. His children were baptized there, showing he was still connected to the wider church. His position became more secure when Rowland Heylyn helped buy control of St Alkmund's Church. Even Herring's enemies admitted he was a loyal subject to the king, despite his views on church ceremonies.

Herring connected with other moderate Presbyterian preachers. He helped make Shrewsbury a center for Puritans. He even brought his brother-in-law, Robert Nicolls, to preach in the town. He also met with other preachers at the home of Lady Margaret Bromley, a supporter of their cause.

Conflict with Archbishop Laud

In the 1630s, religious conflicts in Shrewsbury became very intense. William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury, noticed the strong Puritan presence. Laud was a powerful figure who wanted everyone to follow the Church of England's rules strictly. He even said, "I will pickle up that Herring of Shrewsbury," meaning he would deal with Herring.

Herring responded by saying that if powerful people abused their power, Christians should pray more. He prayed that non-conformists would trust in God when they were treated badly. In 1635, Laud sent someone to investigate churches in the area. Around this time, Julines Herring and his family left Shrewsbury.

Moving to Wrenbury and Amsterdam

Herring first moved to Wrenbury, Cheshire, where his wife's sister lived. He didn't have a formal job there but helped people with their spiritual needs. He had not officially ended his work in Shrewsbury, and the Drapers' Company, who owned his house, had to ask him about unpaid rent.

A New Home in the Netherlands

Herring considered moving to New England but decided against it. He was worried about the growing separatism among Puritans there. In late 1636, he was invited to become a pastor at the English Reformed Church, Amsterdam. This was a big decision, as it meant leaving his family and friends. He also had a large collection of notes and writings that could get his friends into trouble if found. So, he burned most of them, calling it a "Lesser martyrdom."

He had to travel secretly because Laud had forbidden clergy from going abroad without permission. He made a will for his wife and eight children and then left for the coast. He arrived in Rotterdam in September 1637 and then went to Amsterdam.

Life as a Pastor in Amsterdam

Herring's first sermon in Amsterdam was well-received. He quickly became a full part of the Dutch Reformed Church. His family joined him soon after, which was a great relief. After a few years, Thomas Paget, another Puritan minister, joined him at the church.

Amsterdam was a thriving city during the Dutch Golden Age and a strong Protestant area. Here, Herring finally had a platform to preach freely. He was part of a working Presbyterian system, which was what he and other moderate Puritans wanted for England. He spoke out about the situation in England, where King Charles I's rule was leading to conflict. Herring prayed for a Presbyterian system to be set up in England. He made it clear he didn't hate the bishops themselves, but he disliked their "Pride and Prelatical rule." He continued to oppose radical groups that wanted to separate from the church. He even warned his son, who returned to England, not to support any actions against Presbyterianism.

In 1640, he welcomed the Scottish army's invasion of northern England, hoping they would bring good without bloodshed. He prayed for the English Parliament to avoid pride and selfishness. In 1642, the Puritan leaders in Shrewsbury invited Herring to return, but he likely declined. When the English Civil War began, he prayed for England's reformation, even if it meant bloodshed, but also for God to protect his people.

Death

Julines Herring became ill for a long time. His last reported words were, "He is overcome, overcome, through the strength of my Lord and only Saviour Iesus, unto whom I am now going to keep a Sabbath in glory." He died the next morning.

The exact date of his death is debated. Some sources say March 28, 1644. Others suggest 1645, as the Shrewsbury corporation invited him back in 1645 after the town was taken by Parliamentarian forces. Church records in Amsterdam show he was definitely dead by May 18, 1645. His will was approved by his widow, Christian, on March 26, 1646.

Samuel Clarke, who knew Herring, wrote a biography of him in 1651.

Family Life

Julines Herring married Christian Gellibrand while he was preaching at Calke. Christian's father was also a preacher, and her grandfather was a famous Puritan minister. Christian outlived her husband and was still alive in 1651. Her sisters also married Puritan ministers, forming a network that supported Herring's work.

Julines and Christian Herring had 13 children, though only eight were mentioned in Julines's will. One son, Jonathan, may have traveled to the Netherlands with his father. Julines was known for being a loving father who explained to his children why they were being disciplined.

Mapping Julines Herring's Life Journey

| Location | Dates | Event | Approximate coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Llanbrynmair, Powys | 1582 | Birthplace | 52°36′43″N 3°37′39″W / 52.612072°N 3.62745°W |

| More, Shropshire | 1580s | Basic schooling | 52°31′01″N 2°58′08″W / 52.517°N 2.969°W |

| Allesley Green, Coventry | 1582–1610 | Likely parental home. | 52°25′04″N 1°35′00″W / 52.4177°N 1.58346°W |

| Free Grammar School, Coventry | 1590s | Education | 52°24′39″N 1°30′39″W / 52.4107°N 1.5108°W |

| Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge | 1605–9 | Higher education. | 52°12′26″N 0°07′13″E / 52.207222°N 0.120278°E |

| Calke | 1610–18 | First preaching post | 52°47′51″N 1°27′14″W / 52.7974°N 1.4538°W |

| St Alkmund's Church, Shrewsbury | 1618–35 | Lecturer | 52°42′27″N 2°45′08″W / 52.707549°N 2.75225°W |

| St Margaret's Church, Wrenbury | 1635–7 | Assisted vicar William Peartree in private capacity. | 53°01′33″N 2°36′26″W / 53.0257°N 2.6073°W |

| English Reformed Church in the Begijnhof, Amsterdam | 1637–c.1645 | Pastor, largely alongside, Thomas Paget | 52°22′10″N 4°53′25″E / 52.369370°N 4.890150°E |