Thomas Paget (Puritan minister) facts for kids

Thomas Paget (born around 1587, died October 1660) was an English clergyman who believed in the Presbyterian way of organizing the church. He was a Puritan, which meant he wanted to make the Church of England simpler and more focused on the Bible. As a minister in Manchester, he was one of the first to speak out against the new church practices introduced by William Laud, who later became Archbishop of Canterbury.

Paget also served as a pastor in Amsterdam for English Protestants living there. Later, in Shrewsbury, he strongly supported the execution of King Charles I and the new republican government, the Commonwealth of England. He spent his last year as the rector of Stockport.

Quick facts for kids Thomas Paget |

|

| Born | c. 1587 in Possibly Rothley |

|---|---|

| Died | October 1660 in Stockport |

| Nationality | English |

| Church | Church of England, Dutch Reformed Church |

| Education | University of Cambridge |

| Ordained | 6 June 1609 (deacon) |

| Writings | Preface to A Defence Of Church-Government, Exercised in Presbyteri all, Classicall, & Synodall Assemblies (1641) A Demonstration of Family Duties (1643) A Religious Scrutiny (1649). |

| Offices held | Curate and lecturer of Blackley Chapel, Manchester Pastor at English Reformed Church, Amsterdam Curate of Chad's, Shrewsbury Rector of Stockport. |

| Spouse | Margery Gouldsmith |

| Children | Nathan Paget, Dorothy, Elizabeth, Thomas, John, Hanna |

Contents

Early Life and Education

Thomas Paget was the younger brother of another Puritan minister, John Paget. They might have come from the Paget family in Rothley, a village in Leicestershire. We don't know who their parents were or if Rothley was their exact birthplace. Thomas started at the University of Cambridge in 1605. This suggests he was born around 1587.

University Studies

Paget began his studies at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1605. He was a "sizar," which meant he received some financial help with his university costs. He earned his first degree, a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.), in early 1609.

On June 6, 1609, a Thomas Paget from Trinity College was ordained as a deacon. This ceremony was performed by Martin Heton, the Bishop of Ely, in a village called Little Downham. This was likely the start of Thomas Paget's career in the church. He went on to earn his Master of Arts (M.A.) degree in 1612.

Ministry in Manchester

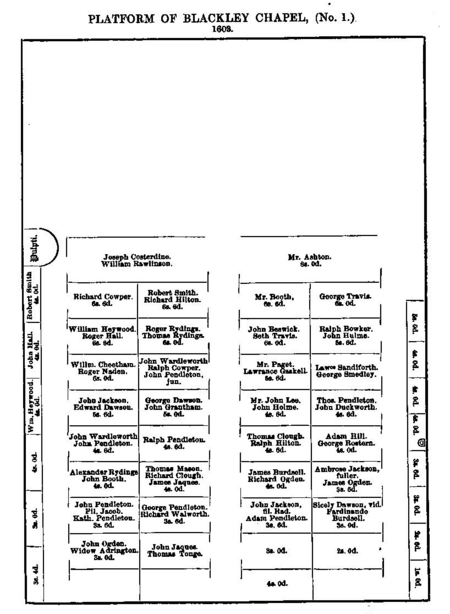

Paget's first job was probably at Blackley Chapel, which was part of the larger parish of St Mary's Church in Manchester. This church had a long history, dating back to 1421. Blackley Chapel itself was even older, licensed for use as early as 1360. Over time, Blackley became known for its strong Protestant beliefs.

Starting at Blackley Chapel

Paget was known as the curate (a minister who helps the main priest) of Blackley in 1620. Two years later, he was called a lecturer, meaning he gave sermons and taught. He started his work there around 1611 or 1612. This was after the chapel became a public place of worship for the local community.

His new job allowed Paget to get married. He married Margery Gouldsmith in Nantwich on April 6, 1613. Their first child, Nathan, was baptized in Manchester in 1615.

Paget's income came from the money people paid for their seats (pew rents) and other donations. The chapel was even renovated during his time there. Paget and other like-minded ministers often met to discuss religious matters. They also took part in "preaching exercises," where several ministers would give sermons at a chapel, offering variety to the congregation.

Facing Challenges and Leaving

In 1617, serious disagreements began between Puritans in Lancashire and the church leaders. King James I visited Lancashire and was asked to relax the rules about Sunday activities. He responded by issuing the "Declaration of Sports." This document allowed people to play games and have fun after church on Sundays. Puritans, who believed Sundays should be strictly for worship, strongly opposed this. Paget was known for his resistance to this new rule.

Paget and other Puritan ministers were called before Bishop Morton for not following church rules. They were accused of "nonconformity." Local officials, called justices of the peace, wrote to the bishop to support the ministers. They praised the ministers' good character and teaching. Bishop Morton, however, was not impressed by this support.

Paget and his colleagues were challenged to explain why they opposed using the sign of the cross during baptisms. Paget spoke for the group, surprising the bishop with his knowledge. Although threatened with suspension, Paget was eventually dismissed with just a warning and a bill for court costs. Bishop Morton later published a book defending the church's ceremonies, partly in response to the Lancashire Puritans.

The next bishop, John Bridgeman, was also strict. Conflict grew over kneeling during communion, another practice Puritans disliked. Paget argued that this practice went against God's commands. As a result, he was suspended from his ministry for two years.

In 1628, Paget's wife died. By this time, King Charles I was ruling, and he was even more opposed to the Puritans. In 1631, Paget and other ministers were ordered to pay fines and were threatened with imprisonment. To escape these troubles, Paget and his family were forced to flee England. They found safety in the Dutch Republic, where his brother John was a pastor in Amsterdam.

Life in Amsterdam

Thomas Paget and his children settled in Amsterdam, living among other English Protestants who had left England. They saw the Dutch community and Scottish Presbyterians as allies in their shared Calvinist beliefs. Paget's eldest son, Nathan, went on to study at universities in Edinburgh and Leiden.

Serving as an Exiled Minister

Thomas Paget likely helped his brother John, who was a wealthy pastor in Amsterdam. Thomas remarried, and a son, also named Thomas, was born in 1635. Another minister in the Amsterdam church was Julines Herring, who had also faced persecution in England.

When his brother John died in 1638, Thomas Paget took over as the pastor of the English Reformed Church in Amsterdam. John's widow, Briget, moved to Dordrecht and helped publish John's writings. In 1639, she published his Meditations of Death, dedicating it to King Charles I's sister, Elizabeth Stuart. This was a politically important act, as Elizabeth was a Protestant hero who supported exiled Puritans.

Speaking Out for Change

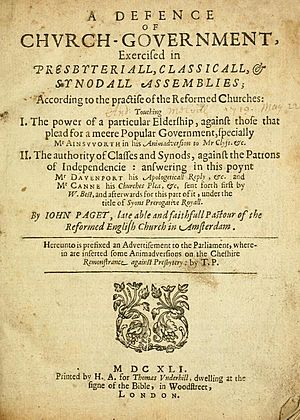

In 1641, Thomas Paget played a key role in English politics. He arranged for his brother's book, A Defence Of Church-Government, to be published in London and presented to the Long Parliament. This book argued for a Presbyterian church structure.

Paget added his own introduction to the book. In it, he spoke about the big changes happening in England. He mentioned how ministers like him had been forced to stay silent for years. He also shared his own experiences of facing challenges from bishops Morton and Bridgeman.

Paget's introduction also criticized a book by Sir Thomas Aston, which supported bishops and opposed Presbyterians. Paget wanted to make it clear that Presbyterianism was different from other Puritan groups. He pointed out that the United Netherlands (Holland) showed that Presbyterianism did not lead to chaos.

More Publications

The changing political situation allowed Thomas's son, Nathan Paget, to return to England in 1640. Nathan became a doctor and supported the Parliamentarian side in the English Civil War. He even married Elizabeth Cromwell, a cousin of Oliver Cromwell.

Thomas Paget stayed in Amsterdam during these years, continuing to lead his church and write. In 1643, he published A Demonstration of Family Duties. This book was a guide for Puritan parents, describing the family as a supportive community that shared a structured daily life. He suggested that mornings and evenings were the best times for families to do religious activities together.

Ministry in Shrewsbury

Around 1645, Paget was invited to Shrewsbury. The town had recently been captured by the Parliamentarians. Royalist clergy were removed, and new ministers were sought. In 1646, the congregation of St Chad's Church chose Paget as their minister.

Paget was definitely working at St Chad's by November 4, 1646. The church records show the burial of his son, John, that day. Another daughter, Hanna, was buried in 1648. The church's name was simply "Chad's," as Puritans often avoided using "Saint."

St Chad's was a large and busy parish. It had a big area, stretching into the countryside. The church records show a lot of baptisms and funerals, even during difficult times. For example, in 1647, there was a big flood. In December of that year, a woman was publicly burned for poisoning her husband. The nearby church of Julian had not had a regular minister for many years, so its congregation often relied on the minister of Chad's.

Presbyterian System in Shropshire

In June 1646, Parliament ordered that Presbyterian church systems should be set up in every county. Shropshire created a system of six "classes" (groups of churches), including one in Shrewsbury. Shropshire was one of only eight counties that actually tried to set up a full Presbyterian system. Paget was named as one of the eight ministers for the Shrewsbury classis.

Paget was the oldest and most experienced minister in the Shrewsbury classis. Other important ministers included Thomas Blake and Samuel Fisher. The lay elders (non-clergy leaders) included the mayor of Shrewsbury and Humphrey Mackworth, the military governor of the town. Mackworth was one of Paget's church members and had a history of opposing the old church practices.

Although the Shropshire plan looked good on paper, it didn't fully work in most parts of the county. Only the Whitchurch classis became fully active. Shrewsbury, under Mackworth, began to follow a different path, and Paget seemed to be a close ally of Mackworth.

Disagreements and Conflict

In 1648, disagreements started to appear in Shropshire. With King Charles I involved in a Second English Civil War, and Presbyterianism linked to a Scottish invasion, more radical groups in the army began to push Parliament for bigger changes. Fifty-seven Shropshire ministers signed a statement against these radical ideas, but Paget did not sign it. This was surprising, as Presbyterianism had been his firm belief for so long.

In 1648, Mackworth prevented a royalist uprising in Shrewsbury. After Parliament removed its moderate members, Mackworth and his officers asked Parliament to bring the king to justice. Mackworth supported the execution of King Charles I and the creation of the republican government. Paget had important family ties to Oliver Cromwell and seemed to have a close relationship with Mackworth.

Using a pen name, Paget published a pamphlet called A Religious Scrutiny, which justified the king's execution. He argued that the law of God applied to everyone, even kings, when it came to murder. He believed the king's execution was a cleansing act that would restore God's favor on England.

When Parliament required a new oath of loyalty to the state, called the "Oath of Engagement," Paget found himself disagreeing with other ministers. This oath required loyalty to the Commonwealth "without a King or House of Lords." This went against an earlier agreement that had supported a Presbyterian church with a king. Ministers like Blake and Fisher refused to take the oath and preached against it. Paget, however, republished his pamphlet on the king's execution to support the new republican government. He believed all oaths were for the safety of England. He still supported a Presbyterian church structure.

For months, the ministers in Shrewsbury preached opposing views. This was noticed in London. In March 1650, Bulstrode Whitelocke, a government official, wrote that ministers in Shrewsbury were preaching against the government and encouraging rebellion. He also noted that some ministers held "mock fasts" to disrupt official fast days.

In July 1650, the bubonic plague broke out in Shrewsbury. The plague began on June 12 and caused many deaths. As the plague worsened, the government put pressure on Mackworth to remove ministers who were stirring up trouble. In August, the government specifically named Blake and Fisher, ordering Mackworth to detain them. The two ministers were forced to leave Shrewsbury later that year, leaving Paget as the only minister in the town center for a while.

Life returned to normal fairly quickly after the plague. In August 1651, Shrewsbury faced another threat when King Charles II's Scottish army approached. Mackworth refused to surrender the town. Paget, along with new ministers Richard Heath and Francis Tallents, were appointed to help remove "scandalous, ignorant, and insufficient or negligent ministers and schoolmasters."

Later Years and New Voices

Paget's influence in Shrewsbury began to lessen after Mackworth's death in 1654. The new governor, the younger Humphrey Mackworth, did not have the same power as his father. New leaders emerged, including Thomas Hunt, a Presbyterian who was friends with Richard Baxter, a famous Puritan minister. They wanted to bring new preachers to Shrewsbury.

Baxter and Hunt tried to bring Henry Newcome to Shrewsbury. The congregation of Julian's Church wanted Newcome and spent money to improve their church. Baxter even wrote to Newcome, suggesting he might eventually take over Paget's church, which was larger.

Newcome, however, was hesitant. In September 1656, he wrote that Paget was "a man of much frowardness" (difficult) and might cause trouble if Newcome came to another church with the intention of replacing him. Baxter tried to reassure Newcome, saying that Paget might not be as difficult as reported. However, Newcome never became a minister in Shrewsbury.

Moving to Stockport

Paget eventually left St Chad's for an easier and better-paying job. After Oliver Cromwell died in 1658, his son Richard Cromwell became the new leader. Richard reinstated John Bradshaw, a strong republican, to an important position. Bradshaw offered Paget the rectory of Mary's Church, Stockport.

Paget accepted the new position, which meant he automatically lost his job at St Chad's. On March 27, 1659, the parish chose John Bryan as their new minister.

Paget and Henry Newcome must have developed a friendly relationship. Newcome, a minister in Manchester, visited Stockport to preach every Friday afternoon. This allowed Newcome and another minister, Richard Heyricke, to visit Paget socially at the rectory. Paget would share memories of his resistance to Bishop Morton, who had once lived in that same rectory.

Paget did not live long in his new post. He saw the restoration of the monarchy (when the king returned to power) but died before the "Great Ejection" of 1662, when many Puritan ministers were forced out of their churches. It seems his declining health led him to resign before his death. His successor, Henry Warren, took over on September 21, 1660.

Death and Family

Thomas Paget died in October 1660. His will, approved on October 16, left his property to his sons, Nathan and Thomas. It also mentioned three surviving daughters: Dorothy, Elizabeth, and Mary. He named his "cousin" Thomas Minshull, an apothecary from Manchester, as the supervisor of his will. Minshull was actually a nephew of Paget's first wife, Margery Gouldsmith.

Paget was married twice. His first wife was Margery Gouldsmith, whom he married on April 6, 1613. She died in 1628. They had at least four children, including:

- Nathan Paget: A well-known doctor and a close friend of the poet John Milton. Nathan introduced Milton to his cousin, Elizabeth Minshull, who later became Milton's third wife.

- Dorothy

- Elizabeth

The name of Paget's second wife is not known. They had at least three children:

- Thomas: Born between 1635 and 1638, he later became a minister and a clerk at Shrewsbury School.

- John: Died as a child in Shrewsbury in 1646.

- Hanna: Buried in Shrewsbury in 1648.

Images for kids

-

The Canons of Dort helped define Calvinist beliefs.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |