Humphrey Mackworth (Parliamentarian) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Humphrey Mackworth

|

|

|---|---|

| Parliamentarian military governor of Shrewsbury | |

| In office March 1645 but not appointed by House of Commons until 2 June 1646 – December 1654 |

|

| Vice Chamberlain of Chester | |

| In office 1648–1654 |

|

| Deputy chief justice of the Chester circuit | |

| In office 1649–1654 |

|

| Member of Protector's Council | |

| In office September 1654 – December 1654 |

|

| Member of First Protectorate Parliament for Shropshire | |

| In office 7 February 1654 – December 1654 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 January 1603 Betton Strange, Shropshire |

| Died | December 1654 (aged 51) London |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 8, including Thomas and Humphrey |

| Relatives |

|

| Profession | Lawyer, politician, soldier, judge, landowner. |

Humphrey Mackworth (1603–1654) was an important English lawyer, judge, and politician from Shropshire. He became famous during the English Civil War in the Midlands, Welsh Marches, and Wales. He served as the military governor of Shrewsbury for the Parliamentarian side during the later parts of the war and under The Protectorate (when England was ruled by Oliver Cromwell).

Mackworth also held several key legal jobs in Chester and North Wales. He oversaw major trials after Charles Stuart (who later became King Charles II) tried to invade England in 1651. In his last year, he became a national figure, joining Oliver Cromwell's Council and serving as a Member of Parliament for Shropshire.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Humphrey Mackworth was born on January 27, 1603. He was the oldest child and only son of Richard Mackworth of Betton Strange, Shropshire. His family, the Mackworths, were a minor gentry family, meaning they owned land and were well-known in their area. They lived just south of Shrewsbury.

The family name came from Mackworth, a village in Derbyshire. The Mackworths of Shropshire were related to the more famous Mackworth baronets from Derbyshire. Humphrey's great-great-grandfather, Thomas Mackworth, started the Shropshire branch of the family.

Humphrey's mother was Dorothy Cranage from Keele, in Staffordshire. Humphrey had two younger sisters, Margaret and Agnes. After Humphrey's father, Richard, died in 1617, his mother Dorothy remarried twice.

Education and Legal Training

Humphrey Mackworth attended schools known for their Calvinist teachings, a branch of Protestantism. He started at Shrewsbury School in January 1614. This school was known for its Protestant education.

In 1619, he went to Queens' College, Cambridge. He was a "Fellow Commoner," which meant he came from a wealthy family and had a special status. The college was popular with some Shropshire families because of John Preston, a puritan preacher.

Mackworth began his legal training at Gray's Inn in London in 1621. He became a lawyer about ten years later. The preacher at Gray's Inn, Richard Sibbes, was also a Puritan. Mackworth became a respected lawyer. He was promoted to "Ancient" (a senior member) of Gray's Inn in 1645. In 1650, he was made a "Bencher," an even higher position, because of his important roles in law and politics.

Early Legal Work and Religious Conflicts

Mackworth took control of his family's estates in 1624, when he was 21. Around the same time, he married Anne Waller. They had a son in 1629. He lived at Betton Strange and worked as a lawyer, splitting his time between Shropshire and London.

In the 1630s, he was a lawyer for the town of Shrewsbury. He became an alderman (a senior town official) in 1633. During this time, King Charles I ruled without Parliament, and religious differences became very important.

Humphrey Mackworth's parish church, St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury, had a history of strong Protestant preaching. However, the new minister, Peter Studley, had different views. He was a "High Church" Anglican, which meant he preferred more traditional, ceremonial worship. This led to conflicts with many people in the church.

In 1633, Studley complained about Mackworth and other families. They refused to bow at the name of Jesus or kneel at the altar rail, which were seen as signs of supporting the King's religious policies. Studley even wrote a book criticizing Puritans.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, also got involved. He ordered churches to adopt more "Catholic" features, like altars and religious pictures. Mackworth was involved in choosing a new minister for St Chad's. The town tried to appoint their own choice, Richard Poole, but Laud challenged this. Eventually, a compromise was reached, and Poole stayed. Mackworth's position as an alderman was confirmed. In 1638, his first wife died, and he married Mary Venables.

When King Charles I had to call Parliament in 1640, people could protest more openly. Mackworth helped organize a protest by Shropshire clergy against a new church oath. This was part of a larger movement that led to the "Root and Branch petition," which asked Parliament to remove bishops from the church.

The English Civil War Begins

Shropshire Falls to Royalists

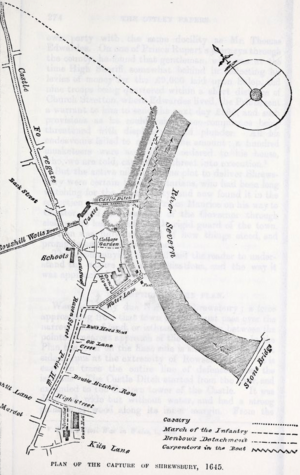

In 1642, as war approached, both the King and Parliament tried to gather forces. Parliament sent leaders like Sir John Corbet, 1st Baronet, of Stoke upon Tern and William Pierrepont to Shropshire. But the King's supporters, led by Francis Ottley, acted faster. The King's army occupied Shrewsbury in September 1642. Ottley, a cousin of Mackworth, was put in charge.

Even though he had family ties to Royalists, Mackworth chose to support Parliament from the start. His name was on a list of "delinquents" (people against the King) in Shrewsbury. The King's army left Shrewsbury in October 1642. The King then ordered the arrest of Mackworth and others, accusing them of treason. Mackworth's lands were taken by the Royalists to help fund their war.

Parliament Fights Back

Mackworth was appointed to several committees by Parliament. These committees aimed to set up a temporary government in areas controlled by Royalists, hoping to recapture them. In February 1643, he joined a committee for Shropshire to raise money for the war.

With help from Sir William Brereton, 1st Baronet from Cheshire, the Shropshire committee gained a foothold in the county at Wem in August 1643. Some committee members, including Mackworth, stayed there. The small garrison at Wem, even with unfinished trenches, fought off a large Royalist attack led by Lord Capel in October. The townspeople, including women, helped fight, and a famous rhyme was made about it. Mackworth was there and took part in the fighting.

The Wem outpost was always in danger. Mackworth was active in the area as a captain in the Parliamentarian army, but also spent time in Coventry and London. In December 1643, he went to London to give evidence against Archbishop Laud. This was about Laud's interference with Shrewsbury's town charter and school.

Meanwhile, the situation in Shropshire worsened as more Royalist soldiers arrived. Mackworth wrote from Coventry in March 1644, describing Shropshire's "bleeding condition" and saying they might have to retreat if help didn't come.

Mackworth's Rise to Power

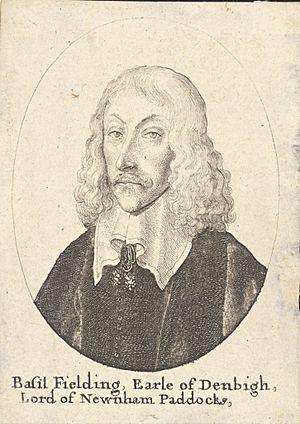

Despite Royalist attacks, the Wem garrison held on. However, arguments started between the military leaders and the civilian committee members. Mackworth had a heated argument with Basil Feilding, 2nd Earl of Denbigh, Parliament's commander in the Midlands. Denbigh even threatened Mackworth.

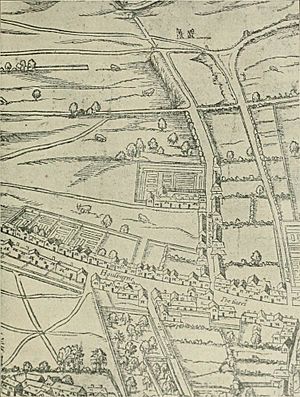

In January 1645, committee members planned to retake Shrewsbury without telling Thomas Mytton, another Parliamentarian leader, because they felt he was difficult. On February 21, 1645, a small force under William Reinking, a Dutch soldier, entered Shrewsbury with the help of a sympathizer. Mytton's cavalry also entered the town.

Mytton expected to be governor of Shrewsbury. However, on February 27, Parliament decided that the Shrewsbury Committee should choose a governor. On March 26, the committee chose "Colonel Humfrey Mackworth." Mytton was the only committee member who didn't agree. Mackworth's appointment was not officially confirmed by Parliament until June 2, 1646. By then, he had already been acting as governor and was also made the town's "Recorder" (a judicial role).

Religious Changes in Shropshire

With Mackworth and the committee in power, they removed Royalist clergy and replaced them with Puritans. The ministers at Holy Cross, St Mary's, and St Chad's churches, and the head of Shrewsbury School, were all replaced. Julines Herring, a Puritan preacher, was invited back from exile.

In 1646, Parliament required each county to plan for a Presbyterian polity (a system of church government). Shropshire was one of the few counties that tried to implement this. Shrewsbury became the center of its first "classis" (a church district), and Mackworth was named one of its ruling elders. Many churches even dropped the "Saint" from their names.

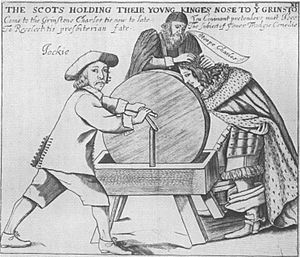

However, much of this plan didn't fully work. The Scottish invasion in 1648, which aimed to restore the King, made Presbyterianism less popular with the New Model Army. The army, which gained political power, favored "Independency" (a different Protestant group) and the execution of the King. Mackworth increasingly supported this more radical view.

Governing Shrewsbury and Beyond

Strengthening Defenses

From 1647, Mackworth's power grew in Shropshire and expanded into Wales. His role as governor was confirmed again by Parliament in March 1647. He faced huge financial challenges and had to deal with defeated Royalists and divisions within the Parliamentarian side.

In June 1647, Mackworth began to increase security in Shrewsbury. This was because King Charles I had been taken from Parliament's custody. Mackworth wrote to the county committee, suggesting they put the town in a "posture of defence," send troops to Ludlow, seize all weapons in the county, and arrest Royalists who hadn't made peace.

Despite this, there were rumors that Mackworth's group was slow to act because they secretly favored the army. In January 1648, Mackworth defended his second-in-command, John Downs, against accusations of disloyalty, showing his loyalty to the army's cause. Shrewsbury's defenses were not fully strengthened until a real Royalist threat appeared in 1648.

Shropshire became involved in the Second English Civil War when John Byron, 1st Baron Byron, a former Royalist commander, tried to start uprisings in 1648. Mackworth discovered and stopped a plot to seize Shrewsbury in April. A larger plot involving Royalists in Herefordshire, Worcestershire, and Shropshire was uncovered in June. About 200 Royalists were surprised at Boscobel.

The Shropshire committee finally acted on Mackworth's earlier warnings. On June 25, they ordered Shrewsbury to be put "into a posture of defence," raise more forces, and repair the walls.

On August 2, another uprising was attempted in Shropshire, supposedly led by Byron. Mackworth learned about it from an informer. Royalist cavalry planned to meet and storm Shrewsbury. Mackworth used his good information to gather forces at Wem. They surprised the Royalists before they could fully assemble, causing them to scatter. Mackworth reported this and asked for more money to reinforce Shrewsbury's defenses. He got what he asked for. He also secured Montgomery Castle for Parliament.

Challenges and Changes

In December 1648, Mackworth and his officers wrote to Fairfax, asking for "justice" against those who caused the war. This was just before Parliament ordered the King's trial. After King Charles I was executed, there was some Royalist unrest, but no major uprising in Shropshire.

In 1650, a new "Oath of Engagement" caused divisions among Puritans. Mackworth's minister, Thomas Paget, supported it, but many other ministers opposed it. Mackworth had to refuse a request from his distant relative, Sir Robert Harley, to live in Shrewsbury because Harley was a moderate Presbyterian who opposed the oath.

A serious outbreak of bubonic plague hit Shrewsbury in June 1650. Mackworth quarantined infected soldiers and moved the administration to Atcham. He ordered the closure of schools and the evacuation of infected houses near the castle. The plague lasted until January 1651, severely affecting the poor.

After the plague, new ministers were appointed. Richard Heath, recommended by Mackworth, became minister at Alkmund's. Francis Tallents took over at Mary's in 1653.

Mackworth also led the county committee that took control of Royalist landowners' estates. He had dealings with the Ottley family, who were Royalists. He helped release their lands from sequestration in 1648, though financial details were still being worked out.

The Crisis of 1651

Charles Stuart, King Charles I's oldest son, was crowned in Scotland in January 1651. In March, the Council of State warned Mackworth about possible Royalist uprisings in Wales. As the English army fought in Scotland, Charles Stuart entered England with a large Scottish army in August, heading south.

Thomas Harrison sent urgent messages to Mackworth and other town governors to warn them. Mackworth's eldest son, Thomas, was an officer in the Shrewsbury garrison, and the town was reported to be in "good posture."

Charles Stuart wrote to Mackworth, asking him to surrender Shrewsbury. He tried to persuade Mackworth by saying he was a "gentleman of an ancient house" and had different principles from Parliament. Mackworth's reply was firm. He addressed Charles as "Commander-in-Chief of the Scottish Army" and refused to surrender. He stated he would remain a "faithful servant of The Commonwealth of England."

On August 27, both letters were read in Parliament. Parliament voted to give Mackworth a medal on a gold chain worth £100 to show their appreciation for his loyalty. Mackworth also used this opportunity to get more money for his garrison. The Scottish army moved on and was defeated by Oliver Cromwell at the Battle of Worcester on September 3.

Legal and Judicial Roles

In September 1647, Mackworth became the Recorder of Wenlock, and later of Bridgnorth. In March 1648, he was appointed Attorney General for North Wales. In June, he was given a special commission to try Royalist conspirators arrested in connection with a plot to seize Chester Castle.

That same year, he became Vice Chamberlain of Chester. This meant he prepared cases for the main judge and filled in for him when he was away. In 1649, Mackworth was appointed deputy chief justice of the Chester legal circuit. He was removed from his Attorney General post to take on this new, more important role.

Mackworth was very active in the trials that followed the Royalist uprisings and invasion of 1651. In October, he presided over the trial of James Stanley, 7th Earl of Derby, who had led an incursion from the Isle of Man. Derby was found guilty and beheaded. Another defector, John Benbow, was also tried by Mackworth and executed by firing squad in Shrewsbury.

At the assizes (court sessions) in April 1652, Mackworth and his colleague presided over the case of a Quaker named Harrison. They sent the case to local magistrates, who decided not to pursue it further.

Mackworth continued to be involved in local law and justice. Records show him attending justice of the peace meetings regularly from 1652 to 1654.

National Importance

For about a year before his death, Mackworth was at the center of national affairs in the new government called The Protectorate.

Member of the Protector's Council

Mackworth was nominated to Oliver Cromwell's Protector's Council in February 1654. He took his seat five days later. He immediately began legal work, including investigating government finances and improving debt collection for London traders.

His duties were varied. He was even on a rota to dine with ambassadors from the Netherlands and France. He spent most of his time in London and was given a government house. The Council met almost every day, and Mackworth attended 159 out of 176 meetings, showing how active he was.

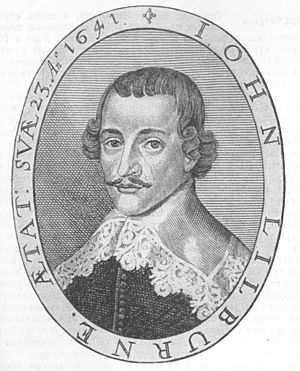

Mackworth was involved in cases dealing with opponents of the government. He was on a committee that recommended sending John Lilburne, a leader of the Levellers (a political movement), to Mount Orgueil Castle on Jersey. He also dealt with disputes, such as one involving a Countess who was breaking down river banks because she opposed a construction project. Mackworth also worked on committees dealing with censorship and social issues like ending cockfighting and preventing duelling.

Member of Parliament

In 1654, Mackworth was one of four elected Members of Parliament for Shropshire in the First Protectorate Parliament. His son-in-law, Philip Young, and his son, Humphrey Mackworth the younger, also became MPs. His brother-in-law, William Crowne, was also an MP.

Parliament began on September 3. Mackworth was immediately appointed to the important "Committee of Privileges," which handled members' freedoms and duties. He also joined committees on various topics, including examining judges' proceedings, preparing for a fast day (a day of public prayer), and investigating "abuses in printing" (censorship). He was also appointed a "Visitor" of the University of Oxford.

During November, Parliament discussed reducing the size of the army. Cromwell listed Shrewsbury as a place needing further consideration, likely influenced by Mackworth's view of its importance. This Parliament was not very successful and was dismissed by Cromwell in January 1655. However, Mackworth had already passed away.

Death and Legacy

Humphrey Mackworth died in London in December 1654, possibly suddenly, as he did not leave a will. He last attended a Council meeting on December 5. He was given a state funeral in the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey on December 26.

His widow, Mary, faced financial difficulties because he died without a will. In March 1655, their house was given to someone else. The Council of State later gave his widow £300 towards funeral costs and paid another £300 in arrears to his son. In 1658, his daughter Anne petitioned the Council for support, and in December, his widow was finally granted a pension.

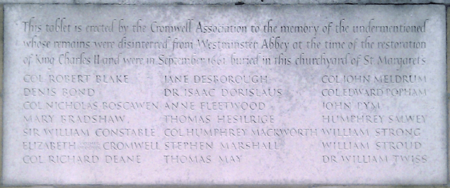

After the King was restored to the throne in 1660, Mackworth was seen as a "regicide" (someone who helped execute the King), even though he wasn't one of the judges at Charles I's trial. In September 1661, his body, along with others buried in Westminster Abbey who had served the Commonwealth, was dug up and reburied in an unmarked pit in the churchyard of St Margaret's, Westminster.

Family Life

Humphrey Mackworth married twice and had children from both marriages.

His first wife was Anne Waller. They married around May 1624. She was buried in 1636. Their children included:

- Thomas Mackworth (1627–1696), Humphrey's main heir.

- Humphrey Mackworth (born 1631), who took over as governor of Shrewsbury after his father.

- Anne, who married a distant relative, Sir Thomas Mackworth, 3rd Baronet.

- Dorothy, who married Thomas Baldwin, the recorder of Shrewsbury.

His second wife was Mary Venables. They married in July 1638. She lived until 1679. Their children included:

- Mary (1641–1671).

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |