July 1936 military uprising in Seville facts for kids

The July 1936 military uprising in Seville was a key part of a bigger plan by some army leaders to take control of Spain. This plan aimed to overthrow the local government in Seville and the western part of Andalusia. The uprising began on July 18, 1936, led by General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano.

The rebel forces quickly took over the main military command and some important army units without a fight. However, they faced resistance from the Guardia de Asalto, a police force loyal to the civil governor, José María Varela. This resistance was overcome later that day. From July 19 to 22, the rebels focused on capturing areas like Triana, Macarena, and San Julián. These areas were controlled by workers' groups and left-wing militias. By July 23, General Queipo de Llano was fully in charge of Seville.

The success of the uprising in Seville was very important for the rebels across Spain. It created a safe area in southwestern Andalusia. This allowed the Army of Africa, a strong rebel force, to be moved to the Spanish mainland. From Seville, these troops could then quickly advance towards Madrid, the capital.

Quick facts for kids July 1936 military uprising in Seville |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish Civil War | |||||||

|

barricade in Macarena district |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| José F. Villa-Abrille José M. Varela |

Gonzalo Queipo de Llano José Cuesta Moreneo |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| few hundred | few hundred | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | 10-20 | ||||||

Contents

Planning the Uprising

Early Plans in Seville

The first signs of a military plot in Seville appeared in early 1936. A group of army officers, led by Comandante Eduardo Álvarez-Rementería, started planning against the government. In April, General Emilio Mola, the main leader of the nationwide plot, sent an officer to Seville. This officer, Colonel Francisco García-Escámez, met with Rementería to set up the basic plans.

By May, a clear leadership for the uprising was in place. It was a group of three army officers, with Comandante José Cuesta Monereo in charge. They built a growing network of supporters. A key member was Comandante Santiago Garrigós, who led the local Guardia Civil.

The plotters also gathered weapons to give to civilian groups like the Falange and Requeté. A loyal officer found some hidden weapons and reported it. The military governor, General José Fernández Villa-Abrille, didn't take action. However, the civil governor, José María Varela Rendueles, reported it to the government in Madrid. But no strong action was taken.

Queipo de Llano Joins the Plot

In June, General Mola met with General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano. Queipo de Llano agreed to join the uprising. Mola asked him to lead the coup in Seville. Queipo de Llano initially wanted to lead in his hometown, Valladolid. But Mola insisted, perhaps because Queipo de Llano was friends with Governor Villa-Abrille. Queipo de Llano then agreed to visit Andalusia to check the situation.

Queipo de Llano traveled around Andalusia in mid-June. He met Villa-Abrille, but it's not clear if Villa-Abrille agreed to join the plot. Villa-Abrille did ask his officers to promise loyalty to the Republic. Meanwhile, some plotting officers were training Falange members.

On June 23, Mola and Queipo de Llano met again. It was decided that Queipo de Llano would lead the uprising in Seville. Mola sent an officer to check on the plans in Seville. The report said that the plot was strong among younger officers, but top commanders were not reliable. Mola concluded that Seville was well-prepared and success was likely.

Final Preparations in July

In early July, Queipo de Llano visited Seville again to ensure everything was ready. Governor Villa-Abrille reportedly left Seville to avoid meeting him. Villa-Abrille was under government watch and didn't want to get involved. He still didn't take specific action to stop any suspicious activities.

On July 16, Queipo de Llano took a train from Madrid to Seville. His actions over the next 24 hours are a bit unclear. He went to Huelva and assured the governor there that he was loyal to the Republic. Some historians think he was planning an escape to Portugal if the coup failed.

Hours Before the Uprising

On July 17, news arrived that a coup was starting in Spanish Morocco. The government ordered the arrest of any officers traveling outside their assigned areas. Governor Varela was told about Queipo de Llano, but because of the earlier assurance of loyalty, he ordered no action. Villa-Abrille also seemed unworried.

That evening, the Seville plotters met to finalize their plans for the next day. A leader of the Communist Party, Manuel Delicado Muñoz, met Varela. He asked for armed patrols of police and workers to watch the military barracks. Varela agreed but refused to give weapons to the workers' groups. During the night, the Air Force commander asked Villa-Abrille to load bombs onto planes at the Tablada airport. These planes were meant to bomb the rebels in Morocco. Villa-Abrille gave the orders, but the plotting officers ignored them.

In the early hours of July 18, Queipo de Llano arrived in Seville from Huelva. He met with civilian plotters and told them the uprising was hours away. Around 11 AM, he visited Villa-Abrille. The meeting was friendly, and they parted ways. Villa-Abrille then gathered his senior officers and asked them to swear loyalty to the Republic.

The Coup Begins

July 18: The First Day

The uprising in Seville started around 2 PM. Queipo de Llano, with other rebel officers, returned to the main military building. Accounts differ, but Villa-Abrille and his staff were disarmed and detained. There was no real resistance. Soon after, Queipo de Llano took over the 6th Granada Infantry Regiment, the largest army unit in Seville. Its commander refused to join and was also detained.

The first shots were fired between 3 and 4 PM. Queipo de Llano sent patrols to declare a state of war. They moved towards the civil government and city hall. The Guardia de Asalto police, on alert, sometimes fought back. There were chaotic shootouts. The loyalist police eventually retreated and barricaded themselves in three buildings in Plaza Nueva: a hotel, the Telefónica building, and the civil government office. The rebels took control of other key places, like the Seville radio station.

In the afternoon, rebel troops blocked access to the city center. This was to stop left-wing militias from advancing. Large crowds gathered in areas like Macarena and Triana, demanding weapons. When they were denied, some tried to seize them. Thousands of people attacked an artillery depot, but the military fought them off, killing about 15 people. Unable to get weapons or reach the center, some people started looting and setting fires. Popular areas saw chaotic violence, and some churches were burned. Workers' unions declared a general strike.

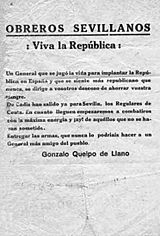

An attempt by the Carlist Requeté to take the civil government building failed. Queipo de Llano demanded Varela's surrender, but it was refused. Around 6:30 PM, the rebels used a mortar and an artillery piece to shell the buildings held by the police. The Telefónica building surrendered first, then the hotel. Varela asked for planes from the Tablada airport to bomb the rebels, but the airport commander refused and instead sent rebel reinforcements. Varela eventually ordered surrender. By night, the city center was fully controlled by the rebels. Workers' districts were in chaos. At 9 PM, Queipo de Llano gave the first of his famous radio speeches.

July 19: Expanding Control

Around 1 AM, the commander of the Tablada air base surrendered to the rebels without a fight. Around 4 AM, a group of Guardia Civil, sent from Huelva to help miners coming to Seville, switched sides and joined the rebels. They fought the miners at the city's edge, and one truck full of dynamite exploded. The miners were eventually defeated. During the night, Falangists who had been arrested were freed from prisons. Communication was set up with Cádiz, which was also taken by the rebels.

Around 9 AM, Queipo de Llano appointed a new city council and mayor for Seville. He also named new civil governors for Seville and Huelva provinces, even though Huelva was still controlled by loyalists. Later that morning, rebel groups, including right-wing militias and some soldiers, began moving into the Gran Plaza district, east of the center. This area was controlled by revolutionary workers. The rebels were well-armed, and the loyalists had few weapons. After some small fights, the area was captured by evening. Rebels searched houses, and men suspected of resisting were beaten, arrested, or executed. Other districts like Triana, Macarena, and San Julián were still held by loyalists. Later that evening, the rebels placed artillery along the Guadalquivir river and began shelling Triana.

In towns and villages around Seville, the situation was confusing. In some places, like Écija, the Guardia Civil joined the coup. In others, like Carmona, the Guardia Civil remained loyal. Some left-wing groups from Carmona tried to go to Seville to fight the rebels, but they didn't reach the city.

In the late afternoon, troops from Ceuta arrived in Seville from Cádiz. Around 7 PM, the first aircraft from Morocco landed at Tablada with soldiers from the Foreign Legion. This began a large airlift operation that lasted for three months. In Madrid, the government was struggling with rebellions across Spain. By nightfall, Queipo de Llano claimed to have about 4,000 men. The rebels controlled a small area between Seville and Cádiz. Uprisings also succeeded in Córdoba, Málaga, and Granada, but these were isolated areas. Neighboring provinces were mostly controlled by the government.

July 20: Battle for Triana

In the morning, rebels gathered their units along the Guadalquivir river to attack Triana. Triana was a maze of narrow streets with barricades. The loyalists had few firearms and mostly improvised weapons. The attack started at Puente San Telmo but quickly got stuck. One rebel group was almost surrounded and had to be rescued. The entire attack was called off.

Throughout the day, the rebels slowly gained more control across the province. Some towns joined the coup, like Marchena. In Osuna, the Guardia Civil, who had been waiting, finally joined the rebels. Communication with Cádiz was now strong. However, there was no link with Córdoba because Carmona, a city on the road, was still loyal to the government. Utrera also remained a loyalist stronghold.

Queipo de Llano continued to appoint new officials for the city and province. He declared himself commander of the military region. He gave a speech from a balcony to the crowd. While some rebel troops still shouted "Long live the Republic," the old Spanish flags were flown from some buildings. In the city center, some services resumed, and strikes were quickly stopped. Left-wing newspapers were shut down, while right-wing papers praised the "patriotic action."

In the afternoon, another attempt to take Triana was launched. This time, the attack was led by Major Antonio Castejón from the Foreign Legion. The rebels were more successful, destroying barricades and advancing into the district. However, they couldn't capture Triana before dark. Fighting in the dark was too risky, so Castejón ordered a retreat. The district remained under revolutionary control.

July 21: Taking Triana and Attacking Macarena

In the early morning, rebel troops launched a third attack on Triana. They first shelled the district with artillery and sniper fire. Three separate groups advanced from different bridges. The rebels used tactics to surround and trap defenders. Those who surrendered were often executed. After a few hours, the resistance ended. Rebels searched the district, which was now covered in white flags, looking for fighters or union activists. Historians describe this as a very harsh and bloody action.

Later that morning, the rebels launched their first attack on the northern loyalist areas, Macarena and San Julián. These districts had been separated from the city center for two days. The inhabitants had been burning churches. The Communist Party leader, Manuel Delicado, convinced the local police commander to give out about 80 rifles. The attack was led by a cavalry squadron. They broke through the first barricades and reached Plaza San Marcos, advancing towards the defense center. However, the attack went wrong, and the commanding officer was killed. The cavalry retreated.

Queipo de Llano issued new orders, declaring a state of war for the entire province. This meant many civil liberties were suspended. Strikes were made illegal, and a curfew was put in place. He also introduced strict laws against looting and arson. All male reserves were called up for military service, and all workers were put under military control. Tram services partially resumed, and debris was cleared. Shops and markets were ordered to open. The press continued to praise the "liberating movement." People arrested in previous days were moved to prisons, but there were no trials or mass executions yet.

In the Seville province, the situation became clearer. Loyalists were trapped in isolated areas, and rebels gained control over most villages and towns. Small rebel groups were sent from Seville to crush resistance in the province. Moroccan troops, who arrived by sea in Cádiz, were immediately sent to fight provincial resistance. Carmona was taken by these troops, establishing a shaky link between Seville and Córdoba. Alcalá de Guadaira, a large town near Seville, was also taken by Queipo de Llano's troops. This removed the last major resistance close to Seville.

July 22: Fall of Macarena

Throughout the morning, rebels gathered troops to capture Macarena and San Julián. This time, they brought a large force, including volunteers, Falangists, Requetés, civilians, Foreign Legion, Civil Guard, police, regular army infantry, cavalry, artillery, and engineers. Queipo de Llano later claimed he took Macarena with 250 men, but historians believe it was thousands. The revolutionary defenders were poorly armed.

The rebel artillery had been shelling the district for some time. The main attack began around 2 PM, led by Major Castejón. Columns attacked from different directions. The rebels used tactics of isolating and surrounding pockets of resistance. Unlike in Triana, there was heavy artillery fire and even air bombing, which damaged some streets. Few prisoners were taken, and those who surrendered were usually executed on the spot.

The plan was for three rebel columns to meet near the Santa Marina church. Two columns advanced as planned, but one from Calle Sol was forced to retreat multiple times before finally reaching Plaza San Marcos. The Foreign Legion soldiers were reported to have used very harsh tactics. In the afternoon, all three columns met, regrouped, and prepared to attack the last loyalist stronghold, Hospicio San Luis.

The final attack was launched in the late afternoon. There were also women and children seeking refuge inside. After close combat, the Hospicio was captured. The loyalist leader, Andrés Palatín Ustriz, was executed as a prisoner. The fighting in Macarena and San Julián was fierce, but rebel troops suffered very few losses. They searched the streets for men. Those found with weapons or suspected of using them were shot immediately. Others were beaten or arrested. About 300 prisoners were paraded through Seville's center. In his radio speech that evening, Queipo de Llano declared that "the punishment has been exemplary." By nightfall, there was no more resistance in the city. The uprising in Seville was over.

Aftermath

In the weeks that followed, the rebels, now often called Nationalists, worked to secure their control in Andalusia. The last remaining areas of loyalist, or Republican, resistance were crushed. For example, Utrera fell on July 26. The Nationalists tried to expand their territory. They failed in the east, where Málaga remained Republican. But they succeeded in the west, capturing Huelva on July 27. This extended their territory to the Portuguese border. By early August, the Nationalist area included most of Seville, Cádiz, and Huelva provinces.

Once in full control, the Nationalists began a massive campaign of repression. The number of people executed during the coup is unknown but likely in the hundreds. An organized campaign of repression began in early August. One historian suggests that 3,000 people were shot in the province in the first weeks after the coup. Another source indicates over 3,000 anonymous bodies buried in the Seville cemetery between July 1936 and February 1937. Official documents later reported nearly 8,000 executions in the province by late 1938.

Queipo de Llano's political stance was unclear. His speeches focused on negative points like "Bolshevism" and chaos. He emphasized patriotism and order, saying he was saving Spain. He sometimes seemed to defend the Republic, even ending his first radio speeches with "Long live the Republic" and the official republican anthem. However, he also ordered the flying of pre-1931 flags. He preferred military leaders but appointed conservatives to civilian roles. He promoted the military's role in the coup and tried to downplay the Falange and Carlists, even though they had armed patrols.

Impact of the Uprising

The successful uprising in Seville was a major victory for the rebels across Spain. Seville was the fourth-largest city in Spain and the largest urban center taken by the rebels. But the strategic gains were even more important. The Seville area became crucial for moving rebel troops from the Army of Africa to the mainland. By the end of July, about 1,000 elite troops were moved, and by August 5, this number grew to thousands, transported by air and sea. The rebels maintained firm control of the area. In early August, western Andalusia became a starting point for the Army of Africa's advance. These African units played a decisive role in the first months of what became the Spanish Civil War.

Although Queipo de Llano was not initially a top leader in the conspiracy, the Seville coup made him one of the most important figures. Other rebel leaders were captured or died. Queipo de Llano became the undisputed leader in the southern rebel zone, acting almost like a "viceroy." However, he did not command the main combat units. The key rebel force, the Army of Africa, was led by Francisco Franco, who soon became the supreme Nationalist commander. Queipo de Llano and Franco had a tense relationship, but Franco allowed Queipo de Llano much freedom in the south, only to reduce his power later.

Key Figures After the Uprising

Rebel Leaders

José García Carranza, a Falange leader and Queipo's assistant, known for his role in the repression, was killed in combat in December 1936. Pedro Parias González, appointed civil governor of Seville by Queipo, served until his death in 1938. Antonio González Espinosa, the first president of the Provincial Council, later became military governor of Seville and died in 1944. Manuel Díaz Criado, an officer in charge of repression, did not rise to major posts and died in 1947.

Gonzalo Queipo de Llano remained the "viceroy" of rebel Andalusia until the end of the war. His relationship with Franco worsened. In 1939, he was sent as an ambassador to Argentina. He retired in 1945 and died in 1952. Santiago Garrigos Bernabeu, the Civil Guard commander, continued his career and died in 1964. Eduardo Álvarez Rementería, a key plotter, held high military and civil posts and died in 1965. Antonio Castejón Espinosa, the Foreign Legion major who led attacks on Triana and Macarena, became a lieutenant general and died in 1969. José Cuesta Moreneo, the conspiracy leader, became chief of staff of the Army of the South and died in 1981. Manuel Escribano Aguirre, a member of the conspiracy leadership, became a brigadier general and died in 1984. Ramón de Carranza Gómez-Pablos, the mayor of Seville appointed by Queipo, was also a long-time president of the Seville Provincial Council and of Sevilla FC. He died in 1988.

Loyalist Figures

José Loureiro Sellés, the Guardia de Asalto commander and loyalist leader, was executed in July 1936 after a quick trial. José Manuel Puelles de los Santos, the president of the Provincial Council, was executed in August 1936. Horacio Hermoso Araujo, the mayor of Seville, was executed in September 1936. Santiago Mateo Fernández, a military commander who seemed confused during the coup, was executed in September 1936.

Saturnino Barneto Atienza, a Communist Party leader, escaped to the Republican zone and later to Moscow, where he died in 1940. General Julián López Viota, an artillery commander who refused to join the rebels, was arrested and died in 1944. General José Villa-Abrille, the loyalist military commander, was imprisoned and died in 1945. Manuel Allanegui Lusarreta, an infantry regiment commander who refused to join the coup, was imprisoned and died in 1958. Rafael Martínez Esteve, the Tablada airport commander, was sentenced to death but later imprisoned. He died in 1965. Manuel Delicado Muñoz, another Communist Party leader, avoided capture and escaped to the Republican zone. He returned to Seville in 1976 and died in 1980. The loyalist civil governor, José Maria Varela Rendueles, was sentenced to death but his sentence was changed to 30 years in prison. He was released at an unknown date and died in 1986.

Historical Views

After taking Seville, Queipo de Llano started a propaganda campaign, praising himself. He claimed he took control of Spain's fourth-largest city with only 130 soldiers, thanks to his bravery and cleverness. Franco initially supported this story but later didn't allow praise for any Nationalist leader except himself. There was even a time in the 1940s when Queipo de Llano was not mentioned in the media. Both Franco's and Queipo de Llano's versions claimed that Seville was a dangerous place full of "Marxist revolutionaries," and the coup saved the city from them. This view continued until the 1990s.

In academic history, it is often said that the coup in Seville succeeded largely because of Queipo de Llano's "boldness and bluff." It is seen as "the revolt's most crucial and audacious single operation." This is because it captured a strong left-wing area and a key strategic location. This allowed the Army of Africa to be brought to the mainland and then advance towards Madrid. However, more recently, historians have focused less on Queipo de Llano's personality and more on the well-developed conspiracy network that had been active in Seville since spring 1936. Some historians aim to show that Queipo de Llano only added the final touches, and that the indecision of local commanders like Villa-Abrille was also a key factor.

See also

In Spanish: Golpe de Estado de julio de 1936 en Sevilla para niños

In Spanish: Golpe de Estado de julio de 1936 en Sevilla para niños

- Gonzalo Queipo de Llano

- José Fernández de Villa-Abrille

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |