Kaʻiulani facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kaʻiulani |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Princess of the Hawaiian Islands | |||||

Kaʻiulani, 1897

|

|||||

| Born | October 16, 1875 Honolulu, Oʻahu, Hawaiian Kingdom (Hawaii) |

||||

| Died | March 6, 1899 (aged 23) ʻĀinahau, Honolulu, Oʻahu, Territory of Hawaii (Hawaii) |

||||

| Burial | March 12, 1899 Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, |

||||

|

|||||

| House | Kalākaua | ||||

| Father | Archibald Scott Cleghorn | ||||

| Mother | Princess Miriam Likelike | ||||

| Religion | Church of Hawaii (Anglicanism) | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Kaʻiulani (Hawaiian pronunciation: [kə'ʔi.u.'lɐni]) was a Hawaiian princess. Her full name was Victoria Kawēkiu Kaʻiulani Lunalilo Kalaninuiahilapalapa Cleghorn. She was born on October 16, 1875, and passed away on March 6, 1899.

Kaʻiulani was the only child of Princess Miriam Likelike. She was the last person who was expected to become queen of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Her aunt was Queen Liliʻuokalani. When Kaʻiulani was 13, she went to Europe for her education. This was after her mother passed away.

In 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom's government was overthrown. This changed Kaʻiulani's life forever. She traveled to the United States to ask for her government to be restored. She gave speeches and appeared in public. She spoke out against the overthrow and the unfairness to her people. She even met with U.S. President Grover Cleveland. But her efforts did not succeed.

After returning to Hawaii in 1897, Kaʻiulani lived as a private citizen. She and Queen Liliʻuokalani did not attend the ceremony where Hawaii became part of the United States in 1898. They were sad about losing Hawaii's independence. Kaʻiulani had health problems in the 1890s. She died at her home in ʻĀinahau in 1899.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Kaʻiulani was born in Honolulu, Hawaii. She was given a long name at her christening. It was Victoria Kawēkiu Kaʻiulani Lunalilo Kalaninuiahilapalapa Cleghorn.

Her main Hawaiian name, Kaʻiulani, means "the highest point of heaven." It can also mean "the royal sacred one" in the Hawaiian language. She was named after her aunt Anna Kaʻiulani. She was also named after Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. Queen Victoria had helped Hawaii keep its independence earlier.

Early Life and Family

Kaʻiulani was the only child of Princess Miriam Likelike. Her father was Archibald Scott Cleghorn, a Scottish businessman. She was born in Honolulu on October 16, 1875. This was during the rule of her uncle, King Kalākaua.

When she was born, she was fourth in line to the throne. She moved to third in line after her uncle Leleiohoku II passed away in 1877. Her father had three older half-sisters from a previous marriage.

Kaʻiulani's mother was related to the first king of Hawaii, Kamehameha I. Her family became the ruling family of Hawaii in 1874. Her mother was the younger sister of King Kalākaua and Queen Liliʻuokalani. Kaʻiulani's father was from Scotland. He worked for the Hawaiian government.

She was christened on December 25, 1875. This was at St. Andrew's Anglican Cathedral in Honolulu. Her godparents included King Kalākaua and Queen Kapiʻolani. Many important people attended the ceremony. The Royal Hawaiian Band played music. The band's leader, Captain Henri Berger, even wrote a song for her.

Princess Ruth gave Kaʻiulani land in Waikiki. Her father bought more land nearby. Together, these lands became ʻĀinahau. Her mother named it ʻĀinahau, which means "cool place." This was because of the cool winds from the Manoa Valley. Her family moved there in 1878 when Kaʻiulani was three. Her father planted a large garden there. It included a famous banyan tree, known as Kaʻiulani's banyan.

Kaʻiulani's mother, Princess Likelike, passed away on February 2, 1887. Kaʻiulani was eleven years old. She inherited the ʻĀinahau estate.

Education and Changes in Hawaii

From a young age, Kaʻiulani had private teachers. They taught her reading, writing, music, and social skills. She learned to speak Hawaiian, English, French, and German fluently.

King Kalākaua wanted future Hawaiian leaders to have a good education. He started a program for Hawaiian youths to study abroad. Kaʻiulani's cousins also studied in the United States and England.

After her mother's death, Hawaii faced political problems. Businessmen were unhappy with the government. In 1887, a group of businessmen created a new constitution. It was called the Bayonet Constitution. This constitution limited the king's power. It gave more power to Euro-American business interests.

Studying in England

After her mother passed away, Kaʻiulani became second in line to the throne. She became the official heir after King Kalākaua died and Liliʻuokalani became queen. In 1889, it was decided that Kaʻiulani should go to England for her education. This would also keep her away from the political problems in Hawaii.

She left Honolulu on May 10, 1889. She traveled across the United States by train. Then she sailed to England. In England, she was cared for by Theophilus Harris Davies and his wife. Davies was a British businessman who owned a large sugar company in Hawaii.

Kaʻiulani attended a boarding school for girls called Great Harrowden Hall. She worked hard and did well in her studies. She was especially proud of her French class. In 1891, her father visited her. They traveled around the British Isles and visited his family's land in Scotland.

Later, Kaʻiulani moved to Hove, Brighton. She had private tutors there. She studied German, French, English, history, and music. She enjoyed living by the sea. She was excited to return to Hawaii in 1893. She wrote to her aunt Liliʻuokalani, "I am looking forward to my return next year. I am beginning to feel very homesick." However, these plans changed when the government was overthrown.

The Overthrow of the Monarchy

While Kaʻiulani was away, many big changes happened in Hawaii. King Kalākaua passed away on January 20, 1891. Kaʻiulani learned about his death the next day. News reached Hawaii later. Liliʻuokalani became queen. On March 9, she officially named Kaʻiulani as the person who would take her place as queen.

As the heir, Kaʻiulani had some influence with the queen. She asked Liliʻuokalani to appoint her father as the Governor of Oahu. The queen agreed. Kaʻiulani also wanted her father to keep his job as collector general. She explained that they needed his salary.

A group called the Committee of Safety planned to overthrow the monarchy. They chose Sanford B. Dole to lead a new government. Dole and Kaʻiulani's father, Archibald Cleghorn, both suggested that Kaʻiulani could become queen. This would happen if Queen Liliʻuokalani stepped down. But the Committee of Safety refused. They did not want any form of monarchy in the future.

The monarchy was overthrown on January 17, 1893. The Provisional Government of Hawaii was then created. Queen Liliʻuokalani gave up her power to the United States temporarily. She hoped the U.S. would help restore Hawaii's government. Cleghorn lost his job as governor. He believed the monarchy could have been saved if Liliʻuokalani had stepped down for Kaʻiulani.

The new government wanted Hawaii to become part of the United States. They offered Liliʻuokalani a yearly payment. They also offered Kaʻiulani a one-time payment. This was if they agreed to Hawaii becoming part of the U.S. But the queen never thought this was a good idea.

Kaʻiulani Visits the United States

Many people in Hawaii and other countries wanted Kaʻiulani to become queen. They thought she could rule under a new, more limited government. James Hay Wodehouse, a British official, said Hawaiians would welcome Kaʻiulani as queen.

Kaʻiulani learned about the overthrow from a telegram on January 30. It said, "Queen Deposed," and "Monarchy Abrogated." Davies, her guardian, told her to take her case directly to the American people.

Kaʻiulani traveled from England to New York. She arrived on March 1. She was with Mr. and Mrs. Davies and other companions. In New York, she met her cousin David Kawānanakoa.

There was some disagreement among the Hawaiian representatives in the U.S. They worried that Davies's influence over Kaʻiulani might hurt their efforts. They felt his public statements supporting a new government with Kaʻiulani as queen would make things confusing.

From March 3 to March 7, Kaʻiulani visited Boston. She attended social events and toured colleges. She arrived in Washington, D.C., on March 8. President Grover Cleveland and First Lady Frances Cleveland met Kaʻiulani at the White House on March 13. They avoided talking about politics during the meeting.

The political situation remained uncertain. Kaʻiulani's father wrote to her. He said it was better for her not to be in Hawaii at that time.

Life in Europe

Before the overthrow, Kaʻiulani received money from the Hawaiian government. This money stopped after the overthrow. Her father's income also ended. This made their financial situation difficult.

Kaʻiulani stayed with the Davies family in England. Davies often wrote public statements under her name. He eventually let her approve them before they were sent to the news. Kaʻiulani spent the summer of 1893 in Ireland. She played cricket and enjoyed tea with friends.

That winter, she traveled to Wiesbaden, Germany. She went with Alice Davies and other young women. They were there to learn German. Alice later said Kaʻiulani "made many conquests among the susceptible German officers." A family friend remembered Kaʻiulani as fun-loving. She enjoyed pillow fights and hide-and-seek.

Kaʻiulani started to enjoy her life abroad. She wrote to her father in 1894. She asked him to consider living in Europe. After a royalist uprising in 1895, he agreed. News of her half-sister Annie's death in 1897 saddened both Kaʻiulani and her father.

From 1895 to 1897, Kaʻiulani and her father traveled across Europe. They stayed in France, on the island of Jersey, and in England and Scotland. Kaʻiulani was treated like royalty in the French Riviera. She made friends there.

During these years, Kaʻiulani often became ill. She wrote to her aunt Liliʻuokalani that she had the flu seven times. She also had headaches, lost weight, and fainted. Her father's money was running out. He asked Liliʻuokalani for help.

Kaʻiulani did not know much about managing money. She depended on the kindness of others. Davies warned her about her spending. He said any money from the new government would mean she had to support their cause. He wanted her to focus on Hawaii. But Kaʻiulani wanted to control her own life. The stress of her financial problems affected her health.

Return to Hawaii

Kaʻiulani felt she had a duty to her family in Hawaii. She especially wanted to see her ailing aunt, Queen Kapiʻolani. But she was tired of her uncertain future. She was also used to her life in Europe. Despite her doubts, the changing political situation in Hawaii called her home in 1897.

On June 16, U.S. President William McKinley presented a new treaty. This treaty would make Hawaii part of the United States. Queen Liliʻuokalani officially protested this. Hawaiians who were against annexation gathered together. They started petition drives to oppose it.

Kaʻiulani decided to return to Hawaii. She and her father sailed from England to New York on October 9, 1897. After a short stay, they traveled to Washington, D.C. They visited Queen Liliʻuokalani, who was there to speak out against annexation.

Kaʻiulani and her father then took a train west. They reached San Francisco on October 29. Many journalists interviewed her during her travels. Her father tried to keep politics out of the interviews. Some people had spread negative rumors about Hawaiians. But interviews with Kaʻiulani changed these ideas. One journalist wrote that she was "a charming, fascinating individual."

Kaʻiulani and her father sailed from San Francisco on November 2. They arrived in Honolulu on November 9. Thousands of people greeted her at the harbor. They gave her garlands of lei and flowers. They returned to ʻĀinahau. Her father had built a new mansion there. Even though she was no longer a royal, she still received visitors. She also attended public events.

In June 1898, the Hawaiian Red Cross Society was formed. Kaʻiulani was named second vice-president. It is not clear if she agreed to this.

The U.S. Senate did not pass the annexation treaty. However, after the Spanish–American War began, Hawaii was annexed anyway. This happened through a special law on July 4, 1898. With Hawaii becoming part of the U.S., Honolulu wanted to show support for American troops. Kaʻiulani and her father invited visiting American troops to stay at ʻĀinahau. Kaʻiulani wrote to Liliʻuokalani, "I am sure you would be disgusted if you could see the way the town is decorated for the American troops."

The annexation ceremony took place on August 12, 1898. It was held at the former ʻIolani Palace. The flag of the Republic of Hawaii was lowered. The flag of the United States was raised. Kaʻiulani told a newspaper, "When the news of Annexation came it was bitterer than death to me." She added, "It was bad enough to lose the throne, but infinitely worse to have the flag go down." Liliʻuokalani, Kaʻiulani, and their family did not attend the ceremony. They stayed at Washington Place in mourning. Many Native Hawaiians also refused to go.

On September 7, 1898, Kaʻiulani hosted a large luau at ʻĀinahau. She welcomed a group of U.S. Congress members and over 120 guests. These officials were working to create a new government for Hawaii. Kaʻiulani organized the event to show the importance of Hawaiian culture. She started the luau by dipping her finger in the poi.

Personal Life

Surfing and Sports

Kaʻiulani was a very active young woman. She loved riding horses, surfing, swimming, and canoeing. In an interview in 1897, she said, "I love riding, driving, swimming, dancing and cycling. Really, I'm sure I was a seal in another world because I am so fond of the water."

Her mother taught her to swim when she was very young. She was a keen surfer at Waikiki. Her surfboard, made of koa wood, is now at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum. It is one of the few old Hawaiian surfboards still existing.

Some people believe she was the first female surfer in the British Isles. However, there is only a letter where she wrote she enjoyed "being on the water again" at Brighton. Her cousins were the first male surfers in the British Isles in 1890.

Art and Friendship

Kaʻiulani was also a painter. She enjoyed spending time with other artists. She sent some of her paintings of England home to Hawaii. Her few remaining paintings are in Hawaii.

She was friends with Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson. He wrote famous books like Treasure Island. Stevenson visited Hawaii and became good friends with King Kalākaua and Kaʻiulani. Stevenson and the princess often walked at ʻĀinahau. They sat together under its banyan tree. Before she left for England, Stevenson wrote a poem for her. He later told a friend, "If you want to cease to be Republican, see my little Kaiulani." Their friendship is a well-known part of Hawaiian history.

Marriage Plans

In 1881, King Kalākaua met with the Emperor of Japan. He suggested a marriage between his 5-year-old niece Kaʻiulani and a 13-year-old Japanese prince. This was meant to create an alliance between the two nations. However, Japan declined the proposal.

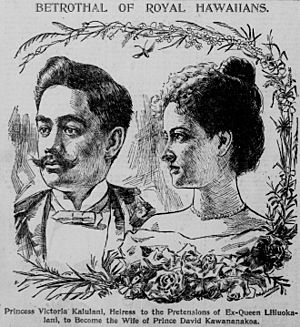

From 1893 until her death, there were many rumors about who Kaʻiulani would marry. As a royal, her marriage would have been important for political reasons. Queen Liliʻuokalani once encouraged her to consider marrying one of her cousins, Prince David Kawānanakoa or Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole. She also mentioned an unnamed Japanese prince. The queen reminded her, "To you then depends the hope of the Nation."

Kaʻiulani responded five months later. She said she would prefer to marry for love. She wrote, "I feel it would be wrong if I married a man I did not love." She had many suitors while she lived in England and Europe. Before returning to Hawaii in 1897, Kaʻiulani told a friend that an arranged marriage was waiting for her in Hawaii. She hinted that it was a secret for political reasons. She felt sad, saying, "I must have been born under an unlucky star as I seem to have my life planned out for me in such a way that I cannot alter it."

There might have been a written agreement for her to marry Prince Kawānanakoa. But it was quickly canceled. A newspaper reported their engagement in 1898. But Kawānanakoa later denied it.

Kaʻiulani's family members have different stories about her relationship with Kawānanakoa. Her niece said they were close like siblings. The Bishop Museum has some of Kaʻiulani's jewelry. This includes a necklace given to her by Queen Kapiʻolani in 1897. It was given to honor her engagement to an unnamed suitor.

Kaʻiulani also mentioned rejecting a proposal from a "very rich German Count." Newspapers also linked her to other suitors.

Death and Burial

Kaʻiulani traveled to the Parker Ranch on the island of Hawaii in December 1898. She attended a wedding and stayed for Christmas. In mid-January 1899, Kaʻiulani and some guests went for a picnic on horseback. The weather turned into a windy rainstorm. Kaʻiulani rode without a raincoat. She started feeling ill later.

Her father and the family doctor came to her. They told the public she was getting better. However, Kaʻiulani was still very weak. Her illness continued. Her father brought her back to ʻĀinahau on February 9. She was so ill that she had to be carried on a stretcher. Doctors said she had "inflammatory rheumatism" and a goitre.

Kaʻiulani passed away at her home in ʻĀinahau on Monday, March 6, 1899. She was only 23 years old. A family friend later told a reporter that she might have died of a broken heart.

Kaʻiulani loved peacocks. She grew up with a flock of them at ʻĀinahau. She was sometimes called the "Peacock Princess." People said her peacocks screamed in the night when she died. This was likely because of the lights and activity. But others believed the peacocks were mourning her.

The government of the Republic of Hawaii gave her a state funeral on March 12. She lay in state at Kawaiahaʻo Church. Hundreds of people joined her funeral procession. An estimated 20,000 people watched in the streets of Honolulu. Her body was taken to the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii for burial. She was buried in the main chapel with her mother and other royals.

In 1910, her family's remains were moved to an underground crypt. Her father was also buried there after his death in 1910.

Legacy and Impact

When Kaʻiulani was born, Honolulu used kerosene lamps for street lighting. In 1888, 12-year-old Kaʻiulani was given the honor of turning on the switch. This switch lit up the city with electric lights for the first time.

In 2007, a British filmmaker started making a movie about Kaʻiulani. It was first called Barbarian Princess. The title was later changed to Princess Kaʻiulani. The movie was released in 2009.

In 1999, a statue of Kaʻiulani was placed in Waikiki. An annual children's hula festival is held in her honor. It takes place in October at the Sheraton Princess Kaiulani Hotel. This hotel is built on the land that used to be ʻĀinahau. In 2017, Hawaiʻi Magazine listed her as one of the most important women in Hawaiian history.

The Kaʻiulani Project

The Kaʻiulani Project started in 2007. Its goal is to share Kaʻiulani's story and her importance to the Hawaiian people. The project works with Hawaiian educators and cultural groups. They create presentations and play readings.

On October 16, 2010, The Kaʻiulani Project held a special event. It was the first time in over 100 years that official Hawaiian ceremonies honored Kaʻiulani. Her grand-niece received offerings in honor of the princess's 135th birthday. The Royal Hawaiian Band performed.

The Kaʻiulani Project also includes a play called Kaʻiulani: The Island Rose. It is based on facts about her life. There is also a biography called Princess Kaʻiulani – Her Life and Times.

ʻĀinahau and Her Banyan Tree

Kaʻiulani's father wanted to give the ʻĀinahau estate to the Territory of Hawaii. He wanted it to be a park to honor Kaʻiulani. But the government refused the gift. The land was sold off. Kaʻiulani's Victorian mansion became a hotel. It later burned down in 1921.

The Daughters of Hawaii organization took care of Kaʻiulani's banyan tree. In 1930, they placed a bronze plaque near the tree. It honored Kaʻiulani and her friendship with Robert Louis Stevenson. However, the tree was cut down in 1949 because it was expensive to care for.

Kaʻiulani Elementary School

Kaʻiulani Elementary School was founded in Honolulu on April 25, 1899. In 1900, the school planted a cutting from Kaʻiulani's banyan tree. This was given to the school by her father. People worked to save this tree in the 1950s. It is still alive today. The bronze plaque from the original banyan tree was moved to this school. Other cuttings from the original tree were planted in other parts of Hawaii.

See also

In Spanish: Victoria Ka'iulani para niños

In Spanish: Victoria Ka'iulani para niños