L'Enfant Plan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

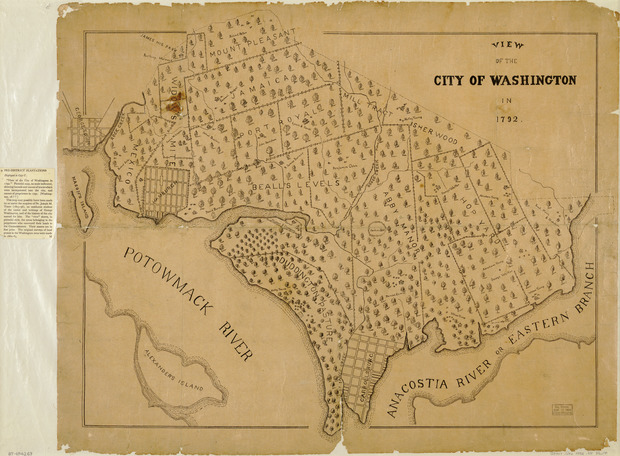

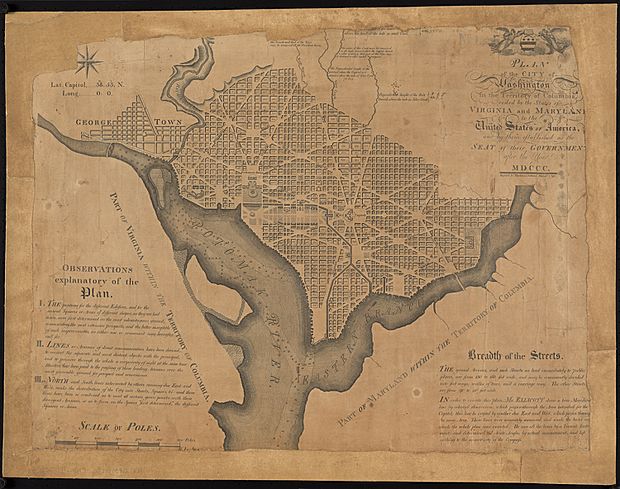

Facsimile of L'Enfant Plan of Washington

|

|

|

|

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 97000332 |

| Designated | April 24, 2019 |

The L'Enfant Plan is a special city design for Washington, D.C.. It was created in 1791 by a French engineer named Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant. He designed it for George Washington, who was the first President of the United States. This plan helped shape how the capital city looks today.

Contents

History of the Plan

Major L'Enfant was a French engineer who fought in the American Revolutionary War. After the war, people started talking about building a new capital city for the United States. In 1789, L'Enfant wrote to President Washington. He asked to be chosen to plan this new city.

The decision about the capital city was put on hold until July 1790. That's when Congress passed a law called the Residence Act. This law said the new capital should be built along the Potomac River. It had to be between the Eastern Branch (now the Anacostia River) and the Conococheague Creek.

The Residence Act also gave President Washington the power to pick three commissioners. These people would help oversee the new federal district. They would also make sure public buildings were ready for the government by 1800.

Planning the Federal City

In 1791, President Washington chose L'Enfant to plan the new "Federal City." L'Enfant worked under the three commissioners Washington had already picked. The new district included the towns of Georgetown and Alexandria, Virginia.

Thomas Jefferson, who was President Washington's Secretary of State, also helped with the planning. Jefferson sent L'Enfant a letter. It asked L'Enfant to draw suitable places for the city and its buildings. Jefferson had simple ideas for the capital. But L'Enfant had much grander plans. He believed he was designing the entire city and its buildings.

L'Enfant arrived in Georgetown on March 9, 1791, and started his work. President Washington met with L'Enfant and the commissioners on March 28. On June 22, L'Enfant showed his first plan for the city to the President. He sent a new map to the President on August 19. President Washington kept a copy of one of L'Enfant's plans. He showed it to Congress and later gave it to the three commissioners.

In November 1791, L'Enfant arranged to get stone from quarries for the "Congress House" foundation. This stone was called "Aquia Creek sandstone." However, L'Enfant was a strong-willed person. He insisted that his city design be built exactly as he planned. This caused problems with the commissioners. They wanted to use the limited money to build the federal buildings first. Jefferson supported the commissioners in this matter.

What the Plan Looked Like

L'Enfant's plan for the city covered a large area. It was bordered by the Potomac River, the Eastern Branch, the base of the Atlantic Seaboard Fall Line, and Rock Creek. His plan showed where two main buildings would go. These were the "Congress House" (now the United States Capitol) and the "President's House" (now the White House).

The "Congress House" was planned for "Jenkins Hill," which is now Capitol Hill. L'Enfant called it a "pedestal awaiting a monument." The "President's House" was planned for a ridge near the Potomac River.

L'Enfant imagined the "President's House" with huge gardens and grand architecture. He wanted it to be five times bigger than the building that was actually built. Even the smaller White House became the largest home built in America at that time. L'Enfant also made the "Congress House" the center point of the city's longitude.

Streets and Avenues

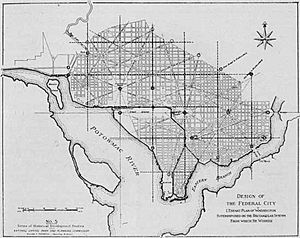

The plan showed that most streets would be in a grid pattern. Some streets would run east-west and be named after letters of the alphabet. Others would run north-south and be named after numbers.

But L'Enfant also added wide, diagonal "grand avenues." These were later named after the states of the Union. These grand avenues crossed the grid streets at circles and square plazas. These open spaces would later honor important Americans.

The plan also marked some circles and plazas as numbered "reservations." Other open spaces were identified by letters. The plan also showed how wide the grand avenues and streets would be.

A key part of L'Enfant's plan was a large right triangle. Its longest side was a wide avenue (now part of Pennsylvania Avenue, NW). This avenue connected the "President's House" and the "Congress House." To complete the triangle, a line went south from the President's House. Another line went west from the Congress House. These lines met at a right angle.

A wide, garden-lined "grand avenue" with a "public walk" was planned. It would stretch for about one mile along the east-west line. L'Enfant chose the west end of this avenue for a future statue of George Washington. However, this grand avenue and the statue were never built as planned. Today, this area is part of the National Mall. In 1793, a wooden marker was placed at the triangle's southwest corner. A small stone monument, the Jefferson Pier, replaced it in 1804.

The plan also suggested building an "historic Column." This column would be in an open space (now Lincoln Park). It would be one mile east of the Congress House. This column would be the point from which "all distances of places through the Continent, are to be calculated."

L'Enfant's plan also included a system of canals. These canals would pass by the "Congress House" and the "President's House." One canal branch would flow into the Potomac River. Another branch would channel James Creek and flow into the Eastern Branch. The canals were a very important part of L'Enfant's grand design for the city. Many important buildings were planned along their banks.

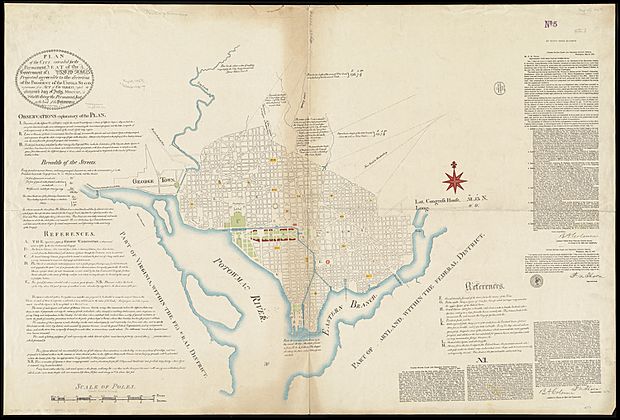

Changes to the Plan by Andrew Ellicott

In 1791, Andrew Ellicott was surveying the boundaries of the federal district. He was also helping L'Enfant plan the city. In February 1792, Ellicott told the commissioners that L'Enfant had not gotten the city plan engraved. L'Enfant also refused to give Ellicott an original copy of the plan.

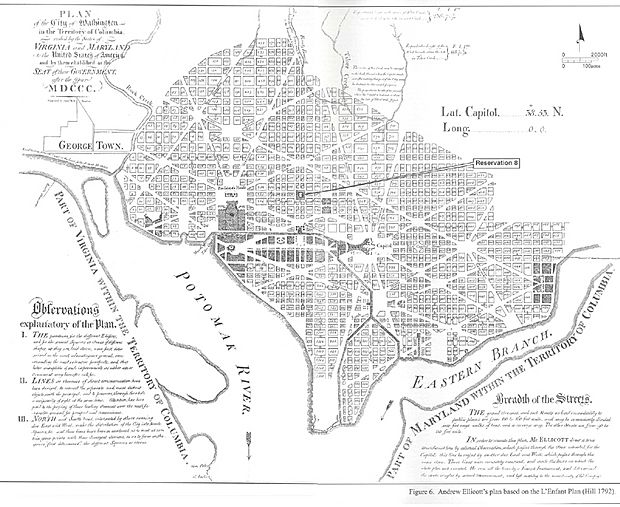

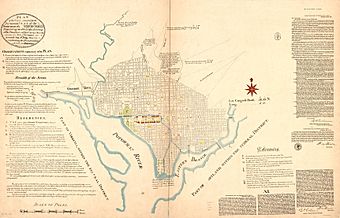

So, Ellicott and his brother, Benjamin, revised the plan. They did this despite L'Enfant's protests. Ellicott's changes included straightening Massachusetts Avenue. He also removed some open spaces and changed some circles into rectangles. His revisions also named L'Enfant's "Congress House" as the "Capitol."

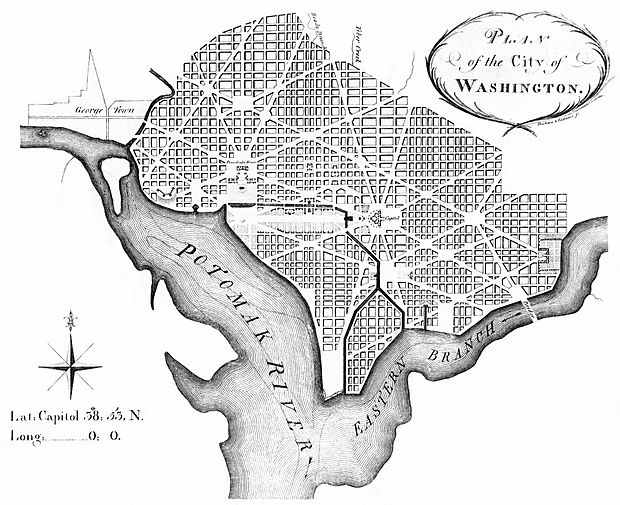

After President Washington dismissed L'Enfant, Andrew Ellicott and his team continued surveying the city. They followed the revised plan. Several versions of Ellicott's plan were engraved, published, and shared in Philadelphia and Boston. Because of this, Ellicott's revised plan became the basis for how the capital city was built.

Ellicott's most complete plan was published in 1792. It showed the names of L'Enfant's "grand avenues" and East Capitol Street. It also showed lot numbers and the depths of the Potomac River and Eastern Branch channels. However, Ellicott's plans did not include L'Enfant's name or the numbered reservations that L'Enfant had put in his plan.

Copies of the Plan

Many copies and versions of L'Enfant's plan have existed over time. In 1899, John Stewart, who worked with public building records, wrote about them. He said President Washington sent one of L'Enfant's handwritten plans to Congress in December 1791. L'Enfant had sent this plan to the President in August 1791. He also made a larger, exact copy. Stewart said surveyors used this copy to lay out the city streets.

Stewart also wrote that President Washington sent another plan to the commissioners in December 1796. This plan had notes from Thomas Jefferson about what parts to leave out when engraving it. Stewart found this plan in 1873.

In 1882, Stewart made a black and white copy of parts of a manuscript plan. This copy had "Peter Charles L'Enfant" written on it. Stewart said it was a true copy of the original.

Five years later, in 1887, the U.S. National Geodetic Survey made a colored tracing of a manuscript plan. This tracing also had "By Peter Charles L'Enfant" on it. This tracing was published in several ways. This helped the plan become widely known for the first time.

The printers added a message to each copy. It said the tracing was made for preservation and reproduction. The original manuscript was in bad shape. It had been mounted on cloth and varnished, making it hard to see through.

The message also explained why the tracing was needed. It was for a court case to help the U.S. Government prove ownership of certain lands. The original plan was so faded it couldn't be photographed well.

In 1930, a librarian at the Library of Congress compared one of the reproduced tracings to another plan. The librarian concluded they were not the same.

The Library of Congress now holds a map that L'Enfant prepared. It was given to the Library for safekeeping in 1918. In 1930, William Partridge described this map. He also noted changes Andrew Ellicott seemed to have made to it.

Partridge noted that L'Enfant said all his drawings were taken in 1791. Only one, a plan for Washington, was recovered. He also said L'Enfant made many versions, but only one (an intermediate version) is still known. Partridge concluded that the origin of the map at the Library of Congress was still uncertain. This map is still the only one bearing L'Enfant's name that is widely known.

In 1991, the Library of Congress made exact copies of this map. They used photography and electronic technology. During this process, they found faint notes made by Thomas Jefferson. These notes are almost impossible to see on the original map. Some differences between L'Enfant's and Ellicott's plans, like the name of the Capitol, come from Jefferson's notes.

The Library believes its Plan is the one L'Enfant gave to President Washington in August 1791. However, others think it's an earlier draft given to Washington in June 1791.

The Library also has a "Dotted line map of Washington, D.C., 1791." It doesn't have an author's name. The Library believes it's a survey map drawn by L'Enfant. It might be the map L'Enfant sent with his August 19, 1791, letter to President Washington. Comparisons suggest Ellicott based his revised plan on this "dotted line map."

Edward Savage's painting, The Washington Family, from 1789–1796, shows L'Enfant's Plan.

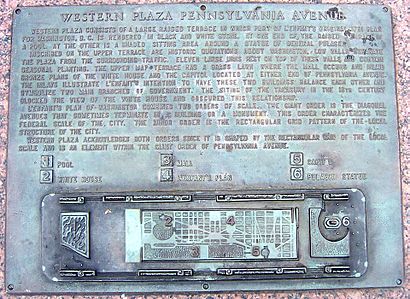

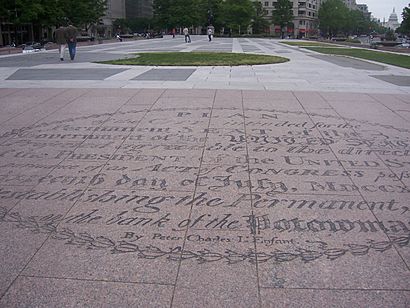

L'Enfant Plan in Freedom Plaza

In 1980, a plaza called Western Plaza was built in Washington, D.C. It was designed by Robert Venturi. In 1988, it was renamed Freedom Plaza. This plaza has a special inlay that shows parts of the L'Enfant Plan. An oval in the plaza has the words "By Peter Charles L'Enfant" written in block letters.

Parks and Avenues from the Plan

Many parks and avenues in Washington, D.C., were part of L'Enfant's original plan.

Contributing Parks

- Reservation 1 President's Park

- Reservation 2–6 National Mall; U.S. Capitol Grounds

- Reservation 7 Judiciary Square

- Reservation 8 Mount Vernon Square

- Reservation 9 Franklin Square

- Reservation 10 Lafayette Square

- Reservation 11 McPherson Square

- Reservation 12 Farragut Square

- Reservation 13 Rawlins Square

- Reservation 14 Lincoln Park

- Reservation 15 Stanton Square

- Reservation 16 Folger Park

- Reservation 17 Garfield Park

- Reservation 18 Marion Park

- Reservation 25–27 Washington Circle

- Reservation 32–33 Freedom Plaza

- Reservation 35–36 Market Square

- Reservation 38–43 Seward Square

- Reservation 44–49 Eastern Market Metro

- Reservation 59–61 Dupont Circle

- Reservation 62–64 Scott Circle

- Reservation 65–67 Thomas Circle

- Reservation 68–69 Gompers Park

- Reservation 152–154; 163–164 Logan Circle

- Reservation 332 West Potomac Park

- Reservation 333 East Potomac Park

- Reservation 334 Columbus Plaza

- Reservation 617 Pershing Park

Contributing Avenues

- Connecticut Avenue

- Delaware Avenue

- Indiana Avenue

- Kentucky Avenue

- Louisiana Avenue

- Maryland Avenue

- Massachusetts Avenue

- New Hampshire Avenue

- New Jersey Avenue

- New York Avenue

- North Carolina Avenue

- Pennsylvania Avenue

- Georgia Avenue (renamed Potomac Avenue in 1908)

- Rhode Island Avenue

- South Carolina Avenue

- Tennessee Avenue

- Vermont Avenue

- Virginia Avenue

Contributing Streets

- 16th Street

- Constitution Avenue

- East Capitol Street

- Independence Avenue

- H Street

- K Street

- North Capitol Street

- South Capitol Street

Images for kids

-

National Archives and Records Administration Letter documenting the return of the L'Enfant Plan to the Office of Buildings and Grounds, December 19, 1888

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |