Lalu Prasad Yadav facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lalu Prasad Yadav

|

|

|---|---|

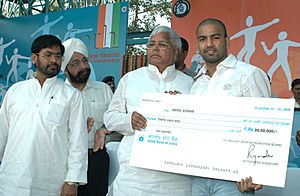

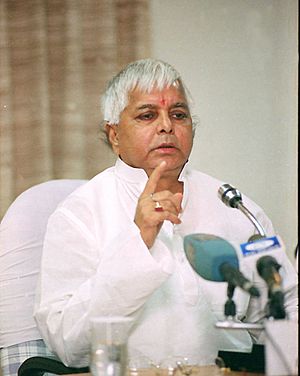

Lalu as Union Minister of Railways, addressing in New Delhi on 12 September 2004

|

|

| 30th Union Minister of Railways | |

| In office 24 May 2004 – 23 May 2009 |

|

| Prime Minister | Manmohan Singh |

| Preceded by | Nitish Kumar |

| Succeeded by | Mamata Banerjee |

| President of the Rashtriya Janata Dal | |

| Assumed office 5 July 1997 |

|

| Preceded by | office established |

| 20th Chief Minister of Bihar | |

| In office 4 April 1995 – 25 July 1997 |

|

| Governor | A. R. Kidwai |

| Preceded by | President's rule |

| Succeeded by | Rabri Devi |

| In office 10 March 1990 – 28 March 1995 |

|

| Governor | Mohammad Yunus Saleem |

| Preceded by | Jagannath Mishra |

| Succeeded by | President's rule |

| Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | |

| In office 22 May 2009 – 3 October 2013 |

|

| Preceded by | constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Rajiv Pratap Rudy |

| Constituency | Saran, Bihar |

| In office 24 May 2004 – 22 May 2009 |

|

| Preceded by | Rajiv Pratap Rudy |

| Succeeded by | constituency abolished |

| Constituency | Chhapra, Bihar |

| In office 10 March 1998 – 26 April 1999 |

|

| Preceded by | Sharad Yadav |

| Succeeded by | Sharad Yadav |

| Constituency | Madhepura |

| In office 2 December 1989 – 10 March 1990 |

|

| Preceded by | Rambahadur Singh |

| Succeeded by | Lal Babu Rai |

| Constituency | Chhapra, Bihar |

| In office 23 March 1977 – 22 August 1979 |

|

| Preceded by | Ramshekhar Prasad Singh |

| Succeeded by | Satya Deo Singh |

| Constituency | Chhapra, Bihar |

| Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha | |

| In office 10 April 2002 – 13 May 2004 |

|

| Constituency | Bihar |

| 12th Leader of the Opposition Bihar Legislative Assembly |

|

| In office 18 March 1989 – 7 December 1989 |

|

| Preceded by | Karpoori Thakur |

| Succeeded by | Anup Lal Yadav |

| Member of Bihar Legislative Assembly | |

| In office 3 March 2000 – 10 April 2002 |

|

| Preceded by | Vijay Singh Yadav |

| Succeeded by | Rama Nand Yadav |

| Constituency | Danapur |

| In office 4 April 1995 – 10 March 1998 |

|

| Preceded by | Uday Narayan Rai |

| Succeeded by | Rajgir Choudhary |

| Constituency | Raghopur |

| In office 8 June 1980 – 2 December 1989 |

|

| Preceded by | Ram Sundar Das |

| Succeeded by | Raj Kumar Roy |

| Constituency | Sonpur |

| Member of Bihar Legislative Council | |

| In office 7 May 1990 – 4 April 1995 |

|

| Constituency | elected by Legislative assembly member's |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 11 June 1948 Phulwariya, Bihar, India |

| Political party | Rashtriya Janata Dal |

| Other political affiliations |

Janata Dal |

| Spouse |

Rabri Devi

(m. 1973) |

| Relations | Tej Pratap Singh Yadav (son-in-law) Chiranjeev Rao (son-in-law) Sadhu Yadav (brother-in-law) Subhash Prasad Yadav (brother-in-law) |

| Children | 9 (including Tejashwi Yadav, Tej Pratap Yadav and Misa Bharti) |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Patna University (B.A.,LLB) |

Lalu Prasad Yadav (born 11 June 1948) is an Indian politician. He served as the Chief Minister of Bihar from 1990 to 1997. He was also the Union Minister for Railways from 2004 to 2009. He is the founder and president of the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), a major political party in Bihar. He has also been a Member of Parliament (MP) in both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha.

Lalu Prasad Yadav is often seen as a champion for lower castes in Bihar. This includes the Other Backward Classes (OBCs), Scheduled Castes (SCs), and Muslim communities. His rise in politics during the 1990s changed Bihar's social and political scene. Before him, upper-caste groups had a lot of power.

He started his political journey as a student leader at Patna University. In 1977, he became one of the youngest members of the Lok Sabha. He became the Chief Minister of Bihar in 1990. His party formed a government in the 2015 Bihar Legislative Assembly election with Nitish Kumar's party. This partnership ended in 2017, and RJD became the opposition.

In the 2020 Bihar Legislative Assembly election, RJD remained the largest party in Bihar. In 2022, RJD and JD(U) formed a government again. This alliance lasted until JD(U) joined another group.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Lalu Prasad Yadav was born on 11 June 1948. He was the fifth of six sons. His parents were Kundan Rai and Marachhiya Devi. He was born in Phulwaria village in Gopalganj district of Bihar. He began his schooling at a local middle school. Later, he moved to Patna with his older brother, Mukund Rai.

He finished his primary education and then attended Government Middle School. This school was near his family's home. His father passed away after he finished high school in 1965. He was a keen footballer at Miller High School in Patna. He later renamed the school to honor a freedom fighter.

He studied at Patna University. He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree. He also worked as a clerk at Bihar Veterinary College in Patna. His eldest brother worked there too. He was the general secretary of the Patna University Students' Union from 1970 to 1971. He then became its President from 1973 to 1974. He later earned his law degree in 1976.

His Siblings

Lalu Prasad Yadav has several siblings. They are listed here from oldest to youngest:

- Mangru Rai

- Gulab Rai

- Mukund Rai

- Mahavir Rai

- Gangotri Devi (his only sister)

- Lalu Prasad Yadav (himself)

- Sukhdeo Rai

Personal Life and Family

Lalu Prasad Yadav married Rabri Devi on 1 June 1973. Their marriage was arranged. They have seven daughters and two sons together.

His Children

Here are his children, listed by age:

- Misa Bharti

- Rohini Acharya

- Chanda Singh

- Ragini Yadav

- Hema Yadav

- Anushka Rao (Dhannu)

- Tej Pratap Yadav

- Rajlaxmi Singh Yadav

- Tejashwi Yadav

Political Journey

1970–1990: Student Leader and Youngest MP

Lalu Prasad started in student politics in 1970. He became the general secretary of the Patna University Students' Union. In 1973, he became its president. He joined Jai Prakash Narayan's Bihar Movement in 1974. This helped him get close to Janata Party leaders. In 1977, he was elected to the Lok Sabha from Chapra. He was only 29 years old, making him one of the youngest MPs.

In 1979, the Janata Party government faced problems. New elections were held in 1980. Lalu left the Janata Party to join a new group. He lost the election in 1980. However, he won the Bihar Legislative Assembly election later that year. He won again in 1985. In 1989, he became the leader of the opposition in the Bihar assembly. Later in 1989, he was also elected to the Lok Sabha. By 1990, he became a key leader for Yadavs and lower castes. Muslims also started supporting him after the 1989 Bhagalpur violence. He became very popular among young voters in Bihar.

1990–1997: Lalu Prasad as Chief Minister of Bihar

In 1990, the Janata Dal party won power in Bihar. Lalu Prasad was chosen to be the Chief Minister. On 23 September 1990, Lalu stopped L. K. Advani's Ram Rath Yatra at Samastipur. This was a significant event. During his first time as Chief Minister, a slogan "Bhurabal saaf karo" (remove upper caste) was used. This term referred to the four main upper castes in the state.

The World Bank praised his party for its economic work in the 1990s. In 1993, Lalu supported bringing back English as a school subject. This was different from other leaders who wanted to remove English. Lalu continued to serve as Bihar's Chief Minister.

1997–2000: Forming RJD and National Politics

In 1997, Lalu Prasad left the Janata Dal party. He formed a new political party called Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD). In the 1998 general election, Lalu won from Madhepura. However, he lost in the 1999 general election. In the 2000 Bihar Legislative Assembly election, his party won, and he remained in the opposition.

2000–2005: Rabri Devi as Chief Minister of Bihar

In 2002, Lalu was elected to the Rajya Sabha. He served there until 2004. In 2000, the RJD formed the government again. This time, Rabri Devi, his wife, became the Chief Minister. Except for a short period of presidential rule, RJD stayed in power in Bihar until 2005.

2004–2009: Union Minister of Railways

In May 2004, Lalu ran in the general election. He won from both Chhapra and Madhepura. RJD won 21 seats in total. It joined with the Indian National Congress to form the UPA I government. Lalu became the Minister of Railways. He later gave up the Madhepura seat.

As railway minister, Lalu did not raise passenger fares. He focused on other ways to earn money for the railways. He stopped the use of plastic cups for tea at railway stations. He replaced them with Kulhars (pottery cups). This was meant to create more jobs in villages. He also planned to introduce buttermilk and khādī linen. He added cushion seats to all unreserved train compartments. In June 2004, he announced he would inspect railway problems himself. He boarded a train from Patna Railway station at midnight.

When he became minister, Indian Railways was losing money. During his time, he claimed a total profit of about 38,000 crore Indian Rupees. Business schools became interested in how he managed this change. The Indian Institute of Management used his work as a case study. Lalu also gave lectures at several top universities.

In 2006, Harvard Business School and HEC Management School in France studied his work. They turned his railway management into case studies. However, in 2009, his successor and other parties said the railway's turnaround was due to different ways of showing financial reports. A 2011 report by the CAG supported this view. The report found that the railway's performance actually declined slightly during his last few years.

2005–2015: Out of Power in Bihar and Center

Bihar Assembly elections were held twice in 2005. The February 2005 election did not result in a clear winner. So, new elections were held in October–November that year. In the October 2005 state elections, RJD won 54 seats. This was fewer than the JD(U) and BJP group led by Nitish Kumar, which came to power. In the 2010 elections, RJD won only 22 seats. The ruling alliance won a record 206 seats.

In the 2009 general election, RJD won 4 seats. They supported the Manmohan Singh government from outside. In May 2013, Lalu tried to energize his party workers. After facing legal challenges in October 2013, Lalu was no longer a member of the Lok Sabha. In the 2014 general election, Lalu Prasad's RJD again won 4 seats.

2015–Current: Grand Alliance

In the 2015 Bihar Assembly elections, Lalu Prasad's RJD became the largest party. They won 81 seats. He and his partner Nitish Kumar of the JD(U) formed a government in Bihar. This was a big comeback for RJD and Lalu after 10 years. However, this alliance did not last long. Nitish Kumar ended the partnership in July 2017. This happened after legal cases were filed against Lalu's son, Tejashwi Yadav.

Positions Held

Lalu Prasad has been elected as a MLA 4 times. He has also been elected as a Lok Sabha MP 5 times.

| # | From | To | Position | Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1977 | 1979 |

|

Janata Party |

| 2. | 1980 | 1985 |

|

Janata Party |

| 3. | 1985 | 1989 |

|

Lok Dal |

| 4. | 1989 | 1990 |

|

Janata Dal |

| 5. | 1990 | 1995 |

|

Janata Dal |

| 6. | 1995 | 1998 |

|

Janata Dal |

| 7. | 1998 | 1999 |

|

RJD |

| 8. | 2000 | 2000 |

|

RJD |

| 9. | 2002 | 2004 |

|

RJD |

| 10. | 2004 | 2009 |

|

RJD |

| 11. | 2009 | 2013 |

|

RJD |

Note:

- 2004: Re-elected to the 14th Lok Sabha (4th term) from Chapra and Madhepura; he kept the Chapra seat. He was appointed Cabinet Minister in the Ministry of Railways in the UPA government.

- 2009: Re-elected to the 15th Lok Sabha (5th term). He ran from two seats. He lost from Pataliputra but won from Saran.

Supporting Lower Castes

Lalu Prasad became very popular among Backward Castes and Dalits. He was criticized for not focusing enough on development. However, a study during his time showed that many people from these groups felt he gave them "ijjat" (honor). For the first time, they could vote as they wished. He started several policies that helped his supporters. These included setting up Charvaha schools for poor children. He also removed a tax on toddy. He made it a serious offense to ignore rules about reservations for "Backward Castes."

Lalu Prasad connected with 'Backwards' through his identity politics. He presented himself as a "Messiah of Backwards." He made sure his lifestyle was similar to his supporters, who were mostly poor. He even lived in a one-room quarter after becoming Chief Minister. Later, he moved to the official residence for work reasons.

Another important change during his time was the hiring of many 'Backward Castes' into government jobs. The rules for hiring were changed to help "Backward Castes." This led to some problems in the administration. However, Lalu continued to lead Bihar because of strong support from "Backward Casts." He focused on giving them "honor," which he felt was more important than development. For lower castes, he was a leader who gave a voice to those who had been silent.

Lalu Prasad also made popular folk heroes of lower castes famous. These heroes were said to have defeated upper-caste rivals. One example is a Dalit saint who was admired for his actions. There is a big celebration every year near Patna for this saint. Lalu Prasad takes part in this fair with great enthusiasm. This makes it a gathering point for Dalits. They see it as their victory and a challenge to upper castes.

According to Kalyani Shankar, Lalu made the oppressed feel like they were the real rulers. He spoke out for them against those who had oppressed them. This helped them gain political power. Before Lalu, upper castes, who were a small part of the population, controlled most of the land. 'Backwards,' who were a larger group, owned very little land. Lalu's arrival led to big changes in the state's economy. 'Backwards' started to have more diverse jobs and own more land.

Lalu also gave Muslims confidence by stopping Lal Krishna Advani's "Rath yatra." Muslims in Bihar felt unsafe after the terrible 1989 Bhagalpur riots. The government at that time could not control the situation. Many poor people were affected. They were looking for a leader who could improve the state. During this time, upper castes lost much of their power. 'Backwards' gained strong control.

Becoming a Leader for Everyone

During his time as Chief Minister, Lalu never tried to act like the old elite leaders. He took part in public festivals. He made his famous Kurta far Holi (cloth tearing Holi) popular. On this day, his guests and media would come to his house shouting. Lalu would respond in a similar playful way. Folk songs were also played. He always called himself the son of a poor Goala (herder). During his Holi celebrations, he would play the Dhol (drum) himself. He would dance to the beat of Jogira songs. Lalu's rallies were called railla, a symbol of strength. People attending these rallies often carried a lathi, a strong stick. This was a symbol of strength and a herder's tool. Drinking Bhang and watching Launda dance made him popular in rural Bihar. However, these activities sometimes bothered the middle class.

Ashwini Kumar noted that Lalu Yadav skillfully combined lower caste and minority politics. This helped him gain control in Bihar. This led to "Total politics," where caste, class, and religion were used to stay in power. Unlike the old Congress-centric politics, Lalu Prasad's new politics was not focused on Brahmins. It was more local and popular.

Working with Government and Other Policies

When Lalu Prasad came to power, more OBC members joined the state assembly. Upper-caste groups faced challenges due to this change. In his second term, after the 1995 elections, OBC lawmakers made up almost half of the assembly. Upper-caste lawmakers dropped significantly. This was a big change from the 1960s. The strong presence of 'Backwards' in the legislature led to disagreements with the bureaucracy. The bureaucracy was still mostly controlled by upper-castes.

There was an increase in corruption. Upper-caste officials used the new lawmakers' "lack of knowledge" to secretly stop good policies. The administrative class often came from land-owning upper-caste families. They tried to block changes to protect their own interests. Lalu Prasad's rise was seen as the end of their power. So, the upper-caste bureaucracy tried to stop the caste-based social justice that Lalu's government wanted. They often ignored orders to keep things as they were. Because of this, the government tried to weaken the bureaucracy. The government, elected to empower OBCs, wanted to bring social justice. This was even if it meant some administrative problems.

At that time, the judiciary also had many upper-caste members. It also disagreed with the government. In 1996, a big financial problem happened in the state. It involved a lot of money missing from the Animal Husbandry Department. At first, the Bihar police were to investigate. This meant the government would control the investigation. But later, the judiciary stepped in. The Supreme Court of India ordered the case to be handled by the Central Bureau of Investigation. The Patna High Court then took charge. This case, called the Fodder Scam, led to more disagreements between the government and the CBI and Judiciary.

Between 1990 and 2005, Lalu Prasad's government took steps to give OBCs, Scheduled Castes, and Muslims more control in government jobs. They were given important roles like District Magistrate. High-ranking officials were also moved around often. In 1993, the top police and chief secretary positions were given to lower-caste officers. The previous officers, who were Brahmins, were removed. Since moving officials around had limits, Lalu's government used quotas to fill these jobs with people from lower-caste backgrounds. If they could not appoint lower castes, the government sometimes left jobs empty. This was to prevent upper castes from getting them.

To weaken the upper-caste bureaucracy, party officials from Janata Dal were allowed to get involved in how things worked. This led to more interference by party members in government and police work. Also, the rise of OBCs and SCs meant that many powerful individuals with criminal backgrounds from these groups gained support. Lalu Prasad was said to have supported several such individuals. Naxal leaders who fought against landlords were invited to join Janata Dal. They were given tickets to run in elections. Any criminal cases against them were dropped during Lalu's time as Chief Minister.

Many people outside Bihar thought that Lalu's government had weak administration and a lot of corruption. But, according to Jeffrey Witsoe, the RJD purposely weakened state institutions controlled by upper-castes. This was to empower lower castes. OBCs were in charge of the government. However, the media, bureaucracy, and judiciary were still controlled by upper-castes. The OBC leaders wanted to end this upper-caste control in other state institutions.

Some people accused Lalu's government of causing tension between different social groups. Many said that under Lalu's rule, farm workers and untouchables started demanding respect and fair wages. Lower castes also fought back when dominant caste groups tried to stop them. In one case in December 1991, a dominant caste group attacked and killed ten Dalit women. In response, left-wing fighters, who were Dalits or Backward Castes, killed thirty-five people from the dominant caste. Historian William Dalrymple wrote about a dominant caste landowner who survived this event. This person blamed Lalu Prasad's government.

Another story from a village called Sargana Gram Panchayat shows the changes Lalu Prasad's government brought. A large Rajput farmer said that the Backwards controlled the government. He felt the government favored them and the harijans. He also felt they supported Muslims.

Some believe Lalu supported the Maoist Communist Centre of India (MCC). During times of caste conflicts, he often visited places where the victims were from Backward Castes. Many people from these castes voted for him because he spoke for them. The poor people in the state did not get many jobs or services. But they were no longer treated badly. Nandini Gooptu mentioned studies from rural Bihar after Lalu Prasad came to power. These studies showed that Schedule Castes like Musahars started demanding their rights, including fair wages.

In the early days of his political rise, Lalu Prasad also caused some members to leave left-wing political parties. These parties had a history with Naxalism. In areas around Nalanda and Aurangabad, the CPI-ML liberation became weaker. This was because the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) led by Lalu Prasad grew stronger. RJD attracted leaders from the Koeri and Yadav castes from the CPI (ML) liberation.

Lalu's rule also changed how elections worked. Before, upper-caste landlords forced their Dalit laborers to vote for certain candidates. But during Lalu's time, farm workers were free to choose their own representatives. This gave many Dalits political freedom.

Earlier, primary schools used as polling stations were in upper-caste villages. Dalits had to go to these villages to vote. This was a problem because upper castes would pressure them. However, journalist Amberish K Diwanji found that Lalu Prasad moved these schools to lower-caste villages. This stopped upper castes from forcing Dalits to vote a certain way. Diwanji also noted strong social ties between Yadavs and Musahars in some parts of Madhepura district. He reported that Yadavs treated Musahars as equals. This bond often led Musahars to vote for Lalu Prasad.

In some rural areas of South Bihar, after Lalu Prasad's Janata Dal came to power, militant groups like Maoist Communist Centre changed their approach. The MCC had many Yadav caste members in leadership. The Schedule Castes were foot soldiers. Before Lalu Prasad in the 1980s, MCC fought a "class war." But after Lalu became Chief Minister, Yadav and Schedule Castes in the MCC supported him.

After several attacks on Dalits, Ranvir Sena, a caste-based group, carried out the Miyanpur attack in 2000. This happened in Aurangabad, Bihar. In this event, over 30 Yadav caste people were killed. However, this event is said to have led to the decline of Ranvir Sena. Lalu Prasad's party, which was in government, took strong actions against Sena. Also, various naxalite groups worked together to fight Sena members.

Political and Other Conflicts

Bihar's society was divided into OBCs, SCs, and Forward Castes (upper caste). The forward castes had controlled the state's democratic institutions under Congress rule. Only a few OBCs were politically aware enough to think about replacing them. This group included three castes: Koeri, Kurmi, and Yadav. They owned land in some parts of Bihar but were poor in areas dominated by forward castes. They rented land from forward castes. Many OBCs also worked in state institutions and were educated professionals in cities. They often faced problems from upper-caste colleagues. This rivalry grew over time.

In rural areas, OBCs also faced challenges from MBCs (Most Backward Castes) and Scheduled Castes. But upper-castes treated all Backward Castes the same way. This caused anger among the elite section of the Backwards. In rural areas, upper-castes fought against MBCs and SCs when they tried to change their traditional village jobs. Upper-castes reacted strongly when MBCs or SCs tried to break away from social roles that symbolized low caste status. For different reasons, OBCs, MBCs, and SCs all faced common rivals: the upper-castes. The bad feelings between OBCs and forward castes grew stronger after anti-reservation protests by upper-castes. This led to these social groups uniting against the forward castes.

Lalu Prasad's rise offered a chance to unite all these groups. Naxalite groups, which had many OBCs in leadership, also supported Lalu's party. Maoist Communist Centre of India, a major Naxalite group, also supported OBC interests. MCC members started giving armed support to MBCs and SCs to vote. This helped Lalu's party candidates win. For a while, the lines between political and Naxalite movements became unclear.

According to Professor Shashi Bhushan Singh, upper-castes (about 20% of the state's population) did not have enough MLAs to control the Backward Castes. So, they used unfair methods to keep power. They would take over polling booths with help from state officials and police, who were mostly upper-caste. This made the state government seem unfair. While most Backward Classes still believed in democratic struggle, some OBCs were drawn to non-democratic groups to fight the forward castes.

Singh said that when Lalu Prasad asked for support from Backward Castes, he wanted to change the entire social order. This was a system where upper castes had the advantage. The reservation policy, based on Mandal Commission recommendations, did not directly benefit Scheduled Castes much. Yet, they supported Lalu Prasad against the forward castes.

A Social Scientist saw Lalu interact with a Musahar caste person during his 2000 Bihar Assembly election campaign. The person asked Lalu for road infrastructure. Lalu reportedly argued that state investments in physical infrastructure mostly helped upper castes. These upper castes had many high-level government and professional jobs. So, he purposely disrupted development until Upper Backward Castes could take over these services. Most District Magistrates during his time were from Upper Backward Castes. He also tried to ensure that middle-level administrative jobs, like Sub Divisional Magistrates (SDM) and Block Development Officer (BDO), were filled by these caste groups. The same approach was used for professionals like Doctors and Engineers.

According to author Arun Sinha, Lalu and his colleague Nitish Kumar came from similar political backgrounds. However, Kumar was more accepted by upper castes regarding quota politics and social justice. One reason was Kumar's step to exclude well-off Backward Castes from reservation benefits. In contrast, Lalu Prasad was seen as strongly against upper castes.

Lalu Prasad and his wife Rabari Devi's time in power saw more violence from the Maoist Communist Centre. During Rabari Devi's time, the Senari attack against the Bhumihars happened. In this event, over 30 Bhumihars were killed. Rabari Devi reportedly did not visit Senari. This was likely because the victims were Bhumihars, who had always opposed her government. It was reported that Lalu Prasad made his wife Chief Minister after facing legal issues. She was said to be not highly educated, but this did not bother the poor of Bihar. Many Bhumihars blame Lalu for their struggles against Dalit-dominated groups like MCC.

Political Symbolism

Lalu's politics is seen as opposing Hindu Nationalism. He used many symbols to challenge politics based on strong religious ideas. In April 2003, he held a large rally at Gandhi Maidan, Patna. This rally aimed to inspire his lower-caste supporters. It also aimed to unite them against the politics of the Bhartiya Janata Party and Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP). At its rally, VHP was giving out Trishuls (a trident symbol) to participants. This was a symbol of strong Hindu identity. Lalu asked his rural supporters to come to Gandhi Maidan with a Lathi (a strong stick). He said this tool of the rural poor, seen as a weapon of the weak, would destroy the Trishul of hatred. This was a hidden attack on the BJP's and VHP's religious politics.

On the day of the rally, Lalu Prasad's rural lower-caste supporters rushed to Patna. Many were brought quickly by local leaders of the Rashtriya Janata Dal. This was to show their support for Lalu Prasad. The rally's theme was, Bhajpa Bhagao Desh Bachao (get rid of Bhartiya Janata Party and save the country). The rally-goers filled the city with Lathis. Many took trains forcefully to Patna. Train windows were broken, and hostels in Patna were taken over for the rally-goers. The crowd was so huge that city traffic was disrupted for two days. Supporters were told to put oil on their Lathis and chant a slogan. This large gathering in Bihar's capital showed that Lalu Prasad had gained real power. The city was full of Lathi-carrying supporters, mostly lower-caste people from rural areas.

1996 Rally for the Poor

Lalu's rallies were a way for him to connect with his rural supporters. In 1996, a huge "rally of the poor" (Gareeb Rally) was organized by Janata Dal. Author Bela Bhatia, who saw this rally in Patna, said that poor people came to Patna. They were given free travel to attend. Janata Dal officials organized many programs for the rally participants. Bhatia mentioned trains running on the Arrah-Patna route. These trains carried more passengers than they could hold. Many people came to Patna to tell the Chief Minister their problems. Some also hoped to get money. Bhatia described an event sponsored by a Janata Dal lawmaker for the rally-goers' entertainment. This showed how Chief Minister Lalu Prasad understood the tastes of his rural supporters.

Promoting Grassroots Workers

Unlike elections often based on money, RJD under Lalu Prasad has promoted political workers from poor backgrounds. They have been given important positions in state politics. This is sometimes done to show Lalu Prasad's support for the poor. In 2022, Lalu led the election of Munni Rajak, a Dalit woman from the Dhobi caste (washerman), to the Bihar Legislative Council. Another example is Ramvrikish Sada, an RJD MLA. Sada has said that he and his family worship Lalu Prasad. Sada, who had been with RJD for thirty years, was reported to be the poorest MLA in Bihar in 2020. He claimed that Lalu Prasad's family gave him money to run in the election. He said he had only 70,000 Indian Rupees in his bank account.

Writings

Lalu Prasad has written his autobiography. It is called Gopalganj to Raisina Road.

Filmography

- Padmashree Laloo Prasad Yadav (Bollywood), as himself (special appearance)

- Mahua (Bhojiwood)

- Gudri Ke Lal (Bhojiwood)

See also

- List of politicians from Bihar

- History of Backward Caste movement in Bihar

Images for kids