Landing at Kip's Bay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Landing at Kip's Bay |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

British troops landing at Kip's Bay in 1776, Unknown author |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,000 | 500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 12 killed and wounded | 50 killed 320 captured |

||||||

The Landing at Kip's Bay was an important event during the American Revolutionary War. It happened on September 15, 1776. British forces made an amphibious landing (meaning they landed from ships onto land) at Kip's Bay in Manhattan. This area was just north of New York City at the time.

British warships fired heavily on the American defenders. This caused the inexperienced American militia to run away. Because of this, the British were able to land easily without anyone fighting back. After the landing, there were small fights. The British almost cut off the escape route for some American soldiers. General George Washington himself was trying to rally his troops. He was left dangerously close to the British lines because his soldiers fled so quickly.

The landing was a big success for the British. It forced the American Continental Army to retreat north to Harlem Heights. This meant the British took control of New York City. However, General Washington set up strong defenses at Harlem Heights. The very next day, a fierce battle happened there. General Howe, the British commander, did not want to risk a direct attack. So, he did not try to move further up the island for two months.

Contents

Why the Landing Happened

The American Revolutionary War had not gone well for the British in 1775 and early 1776. The British army, led by General William Howe, had to leave Boston in March 1776. They went to Halifax, Nova Scotia to get more supplies and soldiers.

General Howe then planned to attack New York City. General George Washington knew this. He moved his army to New York to help prepare defenses. This was hard because there were many places where the British could land.

In July, Howe's troops landed easily on Staten Island. Then, on August 22, they landed on Long Island. Washington's army had strong defenses there. But on August 27, Howe outsmarted Washington in the Battle of Long Island. Washington's army was stuck between the British and the East River. On the night of August 29-30, Washington bravely moved his entire army of 9,000 soldiers across the river to Manhattan.

Even after this clever escape, the American army felt sad and angry. Many militia soldiers, whose time was up, went home. Soldiers even questioned Washington's leadership. Washington asked the Second Continental Congress if he should burn New York City. He wrote that the British would find it useful, but much property would be lost.

Manhattan's Geography in 1776

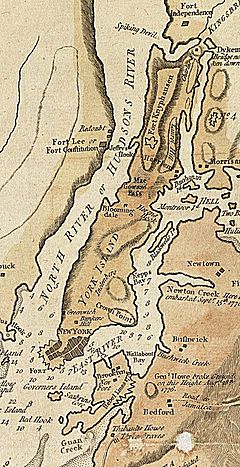

In 1776, Manhattan Island was called York Island. New York City was only at the very southern tip. Greenwich Village was on the western side. The village of Harlem was in the north. The middle of the island had few people and some small hills.

Ferries connected the island to other places. The main ferry to the mainland (now the Bronx) crossed the Harlem River. The Hudson River was on the west side of the island. The East River was on the east, separating Manhattan from Long Island.

Kip's Bay was a small cove on the eastern shore. It was roughly where 32nd to 38th Streets are today. It was a perfect spot for a landing. The water was deep close to shore, and there was a large open field for soldiers to gather. Today, the bay has been filled in and no longer exists.

Planning the Attack

Washington was not sure where General Howe would strike next. He spread his troops out along Manhattan's shores. He also tried to gather information about Howe's plans.

On September 7, there was a very early attempt at submarine warfare. A man named Sergeant Ezra Lee tried to pilot a small submarine called the Turtle. He wanted to attach explosives to the British flagship, HMS Eagle. But his drill hit an iron band on the ship, and he could not attach the bomb. Lee escaped, and the explosives blew up harmlessly in the East River.

Meanwhile, British troops were moving north along the East River. On September 3, a British ship, HMS Rose, towed 30 flatboats up the East River. More ships and flatboats followed.

On September 5, General Nathanael Greene urged Washington to leave New York. Greene argued that without Long Island, New York City could not be held. He said another big defeat would be terrible for the army's morale. He also suggested burning the city. Washington held a meeting with his generals on September 7. A letter arrived from Congress saying New York should not be destroyed, but Washington did not have to defend it. Congress also sent a group to talk with Lord Howe.

Getting Ready for Battle

On September 10, British troops moved to Montresor's Island (now Randall's Island). On September 11, the Congressional group met with Admiral Lord Howe. The meeting did not achieve anything. But it did delay the British attack, giving Washington more time.

In a meeting on September 12, Washington and his generals decided to leave New York City. About 4,000 soldiers under General Israel Putnam stayed to defend the city. The main army moved north to Harlem and King's Bridge. On September 13, major British ship movements began. Warships and transport ships moved up the East River.

By September 14, Americans were quickly moving supplies and sick soldiers north. Every horse and wagon was used. Washington still did not know exactly where the British would attack. By that evening, most of the American army had moved north. Washington followed that night.

General Howe had planned the landing for September 13. He and General Clinton disagreed on where to attack. Clinton thought landing at King's Bridge would trap Washington's army. Howe first wanted two landings, one at Kip's Bay and one further north. But pilots warned him about dangerous waters. So, he decided on just Kip's Bay. After delays due to bad winds, the landing began on the morning of September 15.

The Landing at Kip's Bay

Early on September 15, Admiral Howe sent British ships up the Hudson River. This was a diversion to make the Americans think the attack would be there. But Washington knew it was a trick.

At Kip's Bay, 500 Connecticut militia soldiers had built a small wall for defense. Many of these men were farmers and shopkeepers. They were not experienced soldiers. Some had no guns, only homemade pikes (long poles with blades). They had been awake all night and had not eaten. At dawn, they saw five British warships in the East River.

Around 10 AM, General Sir Henry Clinton ordered the crossing to begin. Over 80 flatboats carried 4,000 British and Hessian soldiers (German soldiers fighting for the British). They left Newtown Cove and headed for Kip's Bay.

Around 11 AM, the five warships began firing their cannons. The sound was terrible. Nearly 80 guns fired at the shore for a full hour. The American defenses were destroyed. The Connecticut militia panicked. They were half-buried under dirt and sand. They could not fire back because of the smoke and dust. When the firing stopped, the British flatboats appeared from the smoke. The Americans were already running away. The British began their landing.

Washington and his aides arrived soon after the landing started. They tried to stop the retreating militia, but they could not. About a mile inland, Washington rode his horse among the men. He tried to turn them around, cursing angrily. Some reports say he lost his temper. He pulled out a pistol and his sword, threatening to hurt the men. He shouted, "Are these the men with which I am to defend America?" When some men refused to fight advancing Hessians, Washington reportedly hit their officers. The Hessians shot or stabbed many Americans who tried to surrender.

Two thousand more American soldiers arrived from the north. But when they saw the chaotic retreat, they also ran away. Washington, still very angry, rode within 100 yards of the enemy. He was so furious that one of his men had to grab his horse's reins and pull him to safety.

More and more British soldiers landed. They spread out in different directions. By late afternoon, 9,000 British troops had landed. General Howe sent a group toward New York City, officially taking control. Most Americans escaped north, but not all. One British officer wrote, "I saw a Hessian sever a rebel's head from his body and clap it on a pole."

The British advance south stopped at Watts farm (near present-day 23rd Street). The northern advance stopped at Murray Hill. General Howe ordered them to wait for the rest of the invading force. This was very lucky for thousands of American soldiers south of the landing point. If Clinton had continued west to the Hudson River, he would have trapped General Putnam's troops. This would have cut off nearly one-third of Washington's army in lower Manhattan.

General Putnam had come north when the landing began. After talking with Washington, he rode south to lead his troops' retreat. They left behind supplies and equipment that would slow them down. His column, guided by his aide Aaron Burr, marched north along the Hudson River. Putnam's men marched so quickly, and the British advanced slowly enough, that only the last American companies fought with the British. When Putnam and his men reached the main camp after dark, they were cheered. Everyone had thought they were lost. Henry Knox also arrived later after a narrow escape. He was greeted with excitement and even hugged by Washington.

What Happened Next

The people remaining in New York City welcomed the British. They took down the American flag and raised the British flag. General Howe was happy. He wanted to capture New York quickly and with little fighting. He saw the invasion as a complete success. Howe did not want to fight more that day, so he stopped his troops before Harlem.

Washington was very angry about how his troops behaved. He called their actions "shameful" and "scandalous." The Connecticut militia were called cowards. However, others understood why they ran. General William Heath said that the American army was still hurting from the Battle of Long Island. He also said that officers knew the city could not be defended. If the Connecticut men had stayed under the heavy cannon fire, they would have been destroyed.

The next day, September 16, there was more fighting. A small clash grew into a larger battle near Washington's lines at Harlem Heights. After several hours, both sides returned to their starting positions. The armies stayed in roughly the same places on Manhattan for the next two months. The American army had held its own against strong British troops. This greatly improved their morale after the disaster of the day before. The British also gained new respect for the American army's ability to fight.

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |