Leverian collection facts for kids

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Established | 1775 |

|---|---|

| Location | Leicester Square, London |

| Collection size | c. 28,000 objects |

The Leverian collection was a huge collection of amazing natural history items and objects from different cultures, put together by Ashton Lever. It was especially famous for the treasures it got from Captain James Cook's voyages around the world. This collection was shown in London for about 30 years before its pieces were sold off in 1806.

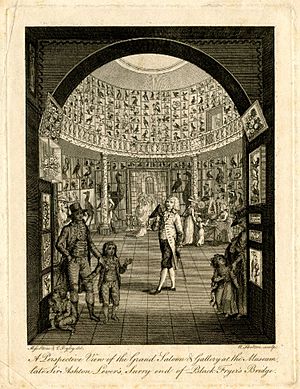

The first public home for this collection was called the Holophusikon, also known as the Leverian Museum. It was located at Leicester House in Leicester Square, London, from 1775 to 1786. After Ashton Lever no longer owned it, the collection was moved. It was then displayed for almost 20 more years at a special building called the Blackfriars Rotunda, just across the River Thames.

Contents

Starting the Collection at Alkrington

Ashton Lever spent many years collecting fossils, shells, and animals. He gathered birds, insects, reptiles, fish, and even monkeys! He kept this huge collection at his home in Alkrington, near Manchester. So many people wanted to see his collection that he was overwhelmed with visitors. He used to let people see it for free. Eventually, he had to say that visitors who arrived on foot could not come in. Because of all this, he decided to move his collection to London and open it as a business, charging an entrance fee.

The Museum at Leicester House

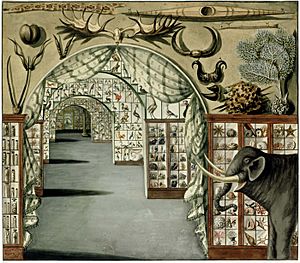

In 1774, Ashton Lever rented Leicester House. He changed the main rooms on the first floor into one big gallery. In February 1775, he opened his museum. It had about 25,000 items, which was only a small part of his total collection. These items were worth more than £40,000! The museum showed many natural items and objects from different cultures. Many of these had been collected by Captain James Cook during his famous voyages. The museum was named after its goal to cover almost everything in natural history. It was like a giant "cabinet of curiosities," filled with all sorts of interesting things.

Lever charged an entry fee of 5 shillings and 3 pence. Or, you could buy an annual ticket for two guineas. The museum was quite successful. In 1782, it made £2,253. To attract more visitors, Lever later lowered the price to two shillings and six pence. He was always looking for new and exciting things to display. He also arranged his exhibits in a way that would impress visitors. Unusually for the time, he also included educational information about the items. However, he spent more money on new exhibits than he earned from tickets.

One person who loved the museum as a boy was Philip Bury Duncan. He later became the keeper of the Ashmolean Museum. Among the many objects on display was a large Viking silver thistle brooch. This brooch was part of the Penrith Hoard, found by a boy in Cumbria in 1785. In 1787, a picture of it was published, claiming it was a symbol of the Knights Templar. The British Museum bought it in 1909.

Selling the Collection by Lottery

Ashton Lever tried to sell his collection. Both the British Museum and Catherine II of Russia (the Empress of Russia) said no. So, Lever got a special law passed in 1784. This law allowed him to sell the entire collection through a lottery. He hoped to sell 36,000 tickets, but he only sold 8,000 tickets at one guinea each.

The collection was won by James Parkinson, who was a land agent and accountant. The collection stayed at Leicester House until Lever died in 1788. The entrance fee was lowered to one shilling.

Moving South of the Thames

James Parkinson moved the Leverian collection to a building specially built for it. This building was called the Rotunda building, located at what is now No. 3 Blackfriars Road. Leicester House itself was torn down in 1791.

A new guide and catalogue for the museum were printed in 1790. Parkinson also asked George Shaw to write a scientific book with illustrations. Artists like Philip Reinagle, Charles Reuben Ryley, William Skelton, Sarah Stone, and Sydenham Edwards helped with the drawings. Some of John White's specimens were shown to the public for the first time here. The museum was also a great place for women to learn and work. Ellenor Fenn wrote a book called A Short History of Insects (1796/7). Its full title said it was "a pocket companion to those who visit the Leverian Museum." She also wrote a similar book about four-legged animals. The artist Sarah Stone continued to work for Parkinson, just as she had for Lever.

Parkinson was quite good at getting naturalists (scientists who study nature) to visit the museum. At that time, it was easier to visit than the British Museum. A visitor in 1799, Heinrich Friedrich Link, said good things about it.

Selling Off the Collection

James Parkinson also tried to sell the museum's contents several times. One attempt was for the government to buy it, but this plan failed because Sir Joseph Banks gave a bad opinion of the collection. In the end, because of money problems, Parkinson sold the collection piece by piece in an auction in 1806.

Some of the buyers included Edward Donovan, Edward Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby, and William Bullock. Many items also went to other museums, like the Imperial Museum of Vienna.

We know a lot about what was in the museum. There was a catalogue made in 1784 and another one for the sale in 1806. Plus, there's a series of watercolour paintings by Sarah Stone that show what was inside. Notes from the sale catalogue help us know, for example, that Alexander Macleay bought 37 different groups of items. The Royal College of Surgeons bought 79 groups. Notes from William Clift also still exist. The items bought by Richard Cuming at the sale started the collection of Richard Cuming. In total, 7,879 groups of items were sold over 65 days.

Surviving Specimens and Objects

Many items from the Leverian collection still exist today!

The specimens bought by Edward Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby were given to the people of Liverpool when he died in 1851. These items became part of the first collection of what is now the World Museum in National Museums Liverpool.

Stanley bought about 117 mounted birds at the auction in 1806. These birds represented about 96 different species. By 1812, 82 of these birds were still around. By 1823, there were 74, and at least 29 by 1850. Today, the World Museum has 25 bird study skins (birds prepared for study) from 22 species that came from the Leverian Sale. Nine of these are known to have been collected during Captain James Cook's second voyage of James Cook and third voyage of James Cook.

Here are some of the birds that survived:

- Black-spotted barbet, adult male.

- Barred honeyeater, adult. This bird was collected during the second voyage of James Cook.

- Pacific long-tailed cuckoo, adult.

- European green woodpecker, adult. This one is a rare "white variety."

- Orange-winged amazon, adult.

- Crested myna, adult.

- Grey-winged trumpeter, adult.

- South Island kōkako, adult. This bird was collected during one of James Cook's voyages from Queen Charlotte Sound / Tōtaranui. This species is now critically endangered and might even be extinct.

- Common Starling, adult. This bird is an albino (all white) version.

- Greater ani, adult.

- Magnificent bird-of-paradise, adult.

- Ancient murrelet, adult.

- ʻŌʻū, adult male and female.

- Racket-tailed treepie, adult.

- Chattering kingfisher, adult. This bird was collected during one of James Cook's voyages.

- Purple-throated fruitcrow, adult.

- Stone partridge, adult.

- Guinea turaco, adult.

- Ruddy shelduck, adult.

- Tui (bird), adult male and female. These birds were collected during the second voyage of James Cook from Queen Charlotte Sound / Tōtaranui.

- Large-billed seed finch, adult. This specimen was actually changed by someone who added fake red feathers to it.

- African swamphen, adult.

Several hundred bird specimens (we don't know the exact number) are in the collection of the Natural History Museum, Vienna. This includes a specimen of the extinct Lord Howe Swamphen.

A number of objects from different cultures also survive in the collections of the British Museum.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |