Library of the Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Library of the Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Country | Spain |

| Type | library |

| Established | 1565 |

| Location | San Lorenzo de El Escorial |

| Website | http://rbme.patrimonionacional.es/ |

The Library of the Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial (Spanish: Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial) is a huge and old library in Spain. It's also called the Escurialense or the Laurentina. King Philip II started this amazing library in 1565. It's located in San Lorenzo de El Escorial and is part of the famous El Escorial monastery.

Contents

Why Philip II Built a Grand Library

King Philip II had several important reasons for wanting to build such a big library in Spain:

- He loved books: The king himself was a very smart person who loved reading and collecting books. It was natural for him to want to create a great library. His own private collection, called the Librería Rica (Rich Library), was the start of the Escorial library.

- A time of new ideas: This was during the Renaissance, a period when people were very interested in learning and new ideas, called humanism. Building a library fit perfectly with this cultural movement.

- A fixed court: The king needed a permanent place for his royal court. A grand library would be a key part of this new, fixed home.

- Wise advisors: Many of the king's helpers were also scholars and book lovers. They gave him great advice on how to build the best library possible. One of the most important was Benito Arias Montano.

How the Library Started and Grew

King Philip II first thought about creating a big library in Spain around 1556. But because the royal court moved around a lot, the project was delayed. The king asked his advisors, like Páez de Castro, to start gathering books for a royal collection.

In 1559, the king decided to build the library at San Lorenzo de El Escorial. This was a bit of a surprise, as his advisors thought places like Salamanca would be better. Salamanca had a university and a strong interest in books. They also worried that El Escorial was too far from major learning centers.

The first books arrived in 1565. These were mostly extra copies of books the palace already had. In 1566, more valuable books came, including the Codex Aureus and a book by Saint Augustine that was supposedly written by his own hand.

Over the next two years, the library grew to over a thousand books. Advisors like Bishop Honorato Juan helped a lot. The library was becoming real! Philip II even met with experts from different fields to get advice on buying more books. They wanted to find original and very old books, as these were considered the most valuable.

The Library Through the Years

Philip II's Time

In 1571, the library bought many books from Gonzalo Pérez, one of the king's advisors who had passed away. This included 57 Greek and 112 Latin old manuscripts. They also bought books from another royal secretary, Juan Páez de Castro, adding 315 books, mostly Greek and Arabic.

The Escorial library became very famous. The king sent "ambassadors" all over to buy books. They bought books from churches and monasteries in Spain. In other European cities, special messengers bought famous works. One very important collection came from Diego Guzmán de Silva, who was an ambassador in Venice. He collected many Greek and Latin old books.

By 1576, the library had 4,546 books, including about 2,000 handwritten manuscripts and 2,500 printed books. That same year, they bought the library of Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, which was considered the most important in Spain. It had over 850 old manuscripts and 1,000 printed books, many from Italy.

The library was so big that Benito Arias Montano spent about ten months organizing and cataloging all the books by language.

In the 1580s, the library got even more important works. Jorge Beteta donated a very old book from the 9th century. About 500 printed books came from the library of Pedro Fajardo. Books that belonged to Queen Isabella I were also brought from Granada. Some of these, like her Books of Hours, are still famous for their beautiful pictures.

The 1590s started with the purchase of a huge library from Antonio Agustín. Not all his books came to El Escorial, but about a thousand did.

Other Kings and Challenges

Philip II died in 1598, but before he passed away, he made sure the library would always have money to buy more books. His son, Philip III, continued this plan. He even made a rule that the Escorial library would get a free copy of every new book published in Spain!

The library kept growing. Arias Montano donated Hebrew books. In 1612, Luis Fajardo captured many Arabic books from Sultan Muley Zidan and sent them to the library.

The Royal Library of El Escorial became a symbol of Spain. In 1656, Philip IV personally arranged for 1,000 more manuscripts to arrive. Many of these came from the library of his important minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares.

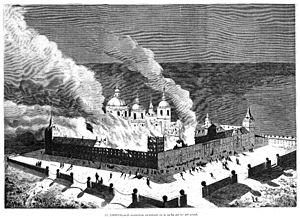

The Great Fire

On June 7, 1671, a huge fire broke out at the Monastery. It caused terrible damage to the library and the entire building. Even though people tried very hard to put out the flames, over 4,000 handwritten books in all languages were lost. Important books like the Visigothic Councils and the 19-volume Natural History of the Indies were destroyed.

To save books, people just grabbed as many as they could. After the fire, the saved books were left in a messy pile for almost 50 years! Finally, in 1725, Father Antonio de San José became the librarian. He spent 25 years reorganizing and cataloging all the books. His new list showed that 4,500 books had survived the fire.

Changes in the 18th and 19th Centuries

In the 18th century, under King Charles III, the library's purpose changed. Before, the goal was to collect as many books as possible. Now, people wanted to share the knowledge from the Escorial library with others. So, they started publishing lists of the books so scholars everywhere would know what was there.

The French invasion in 1808 was another big danger. The French government wanted to move all the books to France. But José Antonio Conde, who was in charge of this, secretly hid the books in a convent in Madrid.

In 1814, King Ferdinand VII ordered the books to be returned. But during the move, many were stolen or lost. Important books like the Cancionero de Baena and the Codex Borbonicus ended up in France. Two Greek Gospel books are now in museums in London and New York. By 1839, 20 manuscripts and 1,608 printed books were missing.

In the mid-1800s, the library's management changed often. In 1837, the Royal Academy of History took over. Later, it was managed by the Royal House. Even with these changes, the library kept making detailed lists of its books and restoring old ones. They also worked hard to get back stolen or borrowed books.

Another fire happened on October 1-2, 1872. It wasn't as bad as the 1671 fire, but it still caused some damage.

The Library Today

In 1875, the Royal Patrimony took over the library. Felix Rozanski, a Polish priest, spent 10 years restoring old manuscripts and fixing fire damage. He also added 5,000 books from Father Claret's library. In 1885, the Augustinian order was put in charge. They were told to make new lists and organize incoming books. By this time, the library was mainly for researchers. They even made the first list of very early printed books, called incunables.

Throughout the 20th century, the Augustinians kept publishing lists for researchers. But over time, the library also started doing something different.

Today, the Royal Library of El Escorial is still a very important place for researchers from all over the world. But it's also a popular tourist spot! Thousands of visitors come every year to see this amazing historical library.

Inside the Library

The Main Hall

This is the most important and impressive part of the library. It's often called the "Main Hall" or the "Hall of Frescoes."

It's 54 meters (about 177 feet) long, 9 meters (about 30 feet) wide, and 10 meters (about 33 feet) high. The most amazing part is the curved ceiling, called a barrel vault, which covers the whole room.

The ceiling is divided into 7 sections. Each section has beautiful paintings called frescoes. These paintings show the seven liberal arts:

- Trivium: Grammar, Rhetoric (the art of speaking well), and Dialectic (the art of reasoning).

- Quadrivium: Arithmetic, Music, Geometry, and Astrology.

Each art is shown with a figure representing it, two stories related to it (from myths, history, or the Bible), and four wise people known for that art. At the ends of the hall, there are paintings of Philosophy (representing learned knowledge) and Theology (representing knowledge from faith).

These paintings were created by Pellegrino Tibaldi in a style called Mannerist, following a plan by Father José de Sigüenza.

On the west side of the Main Hall, there are seven windows with views of the mountains. On the east side, there are five large windows with stained glass and balconies, and five smaller windows, all facing the Court of Kings.

The walls are decorated with many oil portraits. These include paintings of Charles II, Philip II, and Charles V. Sadly, during the French invasion, a famous painting by Velázquez of Philip IV was lost. It's now in London.

You can also see some busts (sculptures of heads and shoulders) in the Main Hall, like one of the sailor Jorge Juan. In one window, there's a special wooden cabinet from the 1700s that holds 2,324 pieces of fine wood.

The four walls have a huge bookcase designed by Juan de Herrera, the architect of the monastery. It's made of beautiful woods like mahogany, cedar, and ebony. It has 54 shelves. In the 1700s, a librarian named Father Antonio de San José added locked wooden lids to some shelves because courtiers often stole books.

The books on these shelves are placed with their page edges facing out, not their spines. This might be because the edges are gilded (decorated with gold), or to show the titles written on them, or simply because the spine is thinner than the edge.

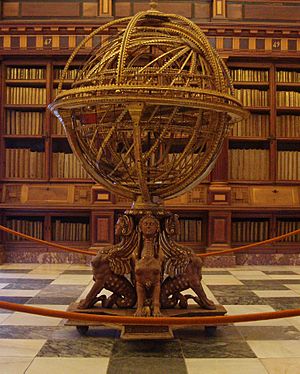

The floor of the Main Hall is made of white and brown marble. In the middle, there's a long wooden table and five smaller gray marble tables. Each table has two bookcases with doors, added in the late 1700s. These tables used to hold globes related to geography and astronomy. One of these old globes is still there.

Today, these tables display the library's most important books, like the Cantigas de Santa Maria by King Alfonso X the Wise.

Other Rooms to Explore

The library has other rooms that are not used as much today, but they were important in the past.

There's the High Hall, located directly above the Main Hall. It used to have shelves, a statue of Saint Lawrence, portraits of popes, and globes and maps, along with many books. It was known for being very cold in winter and hot in summer. Before the Main Hall was finished, all the books were kept here. Later, it was used for many things, like a dormitory for new monks or a place to store forbidden books.

The Summer Hall is next to the Main Hall. It's about 15 meters (50 feet) long and 6 meters (20 feet) wide, with 7 windows. This room used to hold very important handwritten books, organized by language. Today, it mostly holds modern printed books and portraits.

The Hall of Manuscripts was once the monastery's cloakroom. It's 29 meters (95 feet) long and 10 meters (33 feet) wide. It has a curved ceiling like the Main Hall. In the late 1800s, it was used to store handwritten books. This is why these books were saved from the 1872 fire, as that fire didn't reach this room.

There's also the Choir Bookstore, which holds 221 large books used for singing and prayers in the monastery. These books are made of parchment from animal skins and are kept on a single shelf.

Main Book Collections

The library has many different collections of books, especially old handwritten ones called manuscripts.

Latin Books

The Latin manuscripts are the most common in the library. Today, about 1,400 copies remain, but there used to be around 4,000. King Philip II's own small collection of 9 Latin books was the starting point, including valuable ones like the Gospels written in gold letters.

Many Latin books came from the king's advisors, like Tito Livio and Plinio from Gonzalo Pérez's collection. In 1571, the king asked bishops to send him copies of works by Saint Isidore of Seville to make a complete edition. These books ended up staying in the library.

About 2000 priceless Latin books were lost in the 1671 fire. This also meant that the old lists of books were no longer correct. In 1762, King Charles III ordered a new list to be made, which took three years. Today, the Latin manuscripts fill 26 shelves.

Greek Books

At its best, the library had 1,150 Greek books, making it one of the most important collections in Europe. Philip II really wanted to get Greek books from the very beginning.

In 1556, a copyist was sent to Paris to copy many Greek books. Later, advisors like Antonio Pérez and Juan Páez de Castro donated their Greek books. Diego Hurtado de Mendoza also donated 300 Greek manuscripts. Before Philip II died, the Greek collection was a major reference point in Europe.

The 1671 fire destroyed 700 Greek books. More were lost due to thefts during the chaos. Today, there are about 650 Greek manuscripts, filling 9 shelves.

Arabic Books

The Royal Library of El Escorial started with an excellent collection of Arabic manuscripts. The first ones came in 1571. Later, books captured in battles, like the Battle of Lepanto, were added.

In 1573, more Arabic books arrived from Juan de Borja. The biggest addition came from Hurtado de Mendoza, with 256 Arabic manuscripts. By 1580, there were about 360 Arabic books, mostly on medicine. Philip II worked hard to get more. After his death, there were about 500 Arabic manuscripts.

In 1614, the library received the entire collection of Muley Zidan, the Sultan of Morocco, adding 3,975 books! In 1651, when the Sultan asked for his library back, he was refused.

The 1671 fire destroyed 2,500 Arabic books. Some valuable ones, like a Quran captured at Lepanto, were saved. In 1691, when Morocco again asked for their library, they were told all the books had burned. In 1766, some books were given back as gifts, but the librarians hid the most valuable ones.

Today, the library still has almost 2,000 Arabic manuscripts, thanks to good cataloging and study over the years.

Hebrew Books

The Hebrew collection, at its largest, had about 100 valuable books. These were rare in Spain because of the Inquisition (a historical court that persecuted certain groups).

The first Hebrew books arrived in 1572, including a Bible written on parchment. Benito Arias Montano, who was an expert in Hebrew, helped add more ancient and beautiful Hebrew works. In 1576, Hurtado de Mendoza donated 28 Hebrew manuscripts. More were added around 1585, taken by the Inquisition.

The 1671 fire destroyed 40 Hebrew manuscripts, which was more than a third of the collection. After this, the Hebrew books were stored with books forbidden by the Inquisition.

Today, there are fewer than 80 Hebrew books. The most important is the Bible of Arias Montano.

Castilian Books

The Castilian (Spanish) manuscripts were not as many as the Latin or Greek ones, but they were very high quality. Philip II kept books written in Spanish, even though some people at the time thought books in other languages were more important.

Important Castilian manuscripts included works by Francisco de Rojas, Juan Ponce de León, and Antonio de Guevara. Books by Francisco Hernández, Alfonso X the Wise, and Juan Bautista de Toledo also came from the palace. In 1576, 20 Castilian books, including the Cancionero de Baena, arrived from Hurtado de Mendoza's library.

The 1671 fire was very damaging to the Castilian collection too. After that, not many new Castilian books were added. Today, these manuscripts are kept in the Hall of Manuscripts.

Other Languages

The library also has smaller collections of books in other languages:

- Armenian: Two old books, one from Hurtado de Mendoza's library.

- Chinese/Japanese: 40 very important books, mostly given by Gregorio Gonzálvez to Philip II.

- Catalan/Valencian: About 50 old books, including a special one from the late 1200s.

- French: Fewer than 30 remain today, but they once had almost 100. A beautiful Breviary of Love with illustrations stands out.

- German: Two old books written on parchment.

- Italian: About 80 books, many about music.

- Persian/Turkish: Almost 30 remain, many believed to be from the Battle of Lepanto.

- Portuguese/Galician: Only 15, but very special, related to Alfonso X the Wise and Queen Isabella I.

See also

In Spanish: Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial para niños

In Spanish: Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial para niños