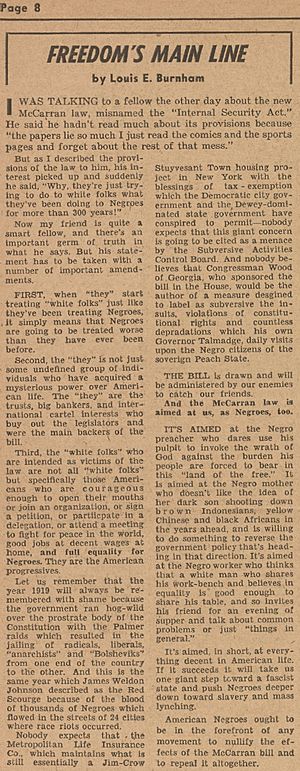

Louis E. Burnham facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louis Everett Burnham

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | September 29, 1915 |

| Died | February 12, 1960 (aged 44) New York City, US

|

| Burial place | Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York |

| Education | Social science degree, a year of law school |

| Alma mater | City College of New York |

| Occupation | Activist, editor, writer |

| Years active | 1932–1960 |

| Employer | Southern Negro Youth Congress, Progressive Party, Freedom, National Guardian |

| Organization | Frederick Douglass Society, Harlem Youth Congress, National Negro Congress, Young Communist League, Alabama Committee for Human Welfare |

| Known for | Activism, journalism |

|

Notable work

|

Behind the lynching of Emmett Louis Till, creation and management of and columns in Freedom, columns in National Guardian |

| Political party | Communist Party, USA |

| Movement | Civil rights movement, Voting rights |

| Opponent(s) | |

| Board member of | Southern Conference Educational Fund |

| Spouse(s) | Dorothy (née Challenor) Burnham |

| Children | Claudia Burnham Margaret Burnham Linda Burnham Charles Burnham |

| Relatives | Forbes Burnham |

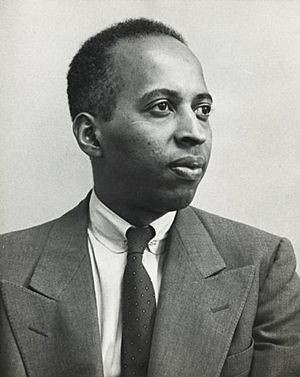

Louis Everett Burnham (September 29, 1915 – February 12, 1960) was an African-American activist and journalist. From his college days, he worked hard for racial equality. He was involved in many groups and publications in both the northern and southern United States. He focused especially on New York City and Birmingham, Alabama.

Contents

Louis Burnham's Life Story

Growing Up and School

Louis Everett Burnham was born in Harlem, New York City. Some say he was born in Barbados. His parents, Charles and Louise Burnham, were immigrants from Barbados. Louis was a cousin of Forbes Burnham, who later became the Prime Minister of Guyana. His mother was a follower of Marcus Garvey, who believed in black nationalism. She taught Louis to be proud of his heritage.

In 1932, Louis graduated from Townsend High School. He was a talented violinist. He also did very well in college at City College of New York (CCNY). He even wrote papers for other students to earn money. During this time, he led the Harlem Youth Congress.

While at CCNY, Louis became very interested in the Civil Rights Movement. He helped start the American Student Union (ASU). He also led the Frederick Douglass Society, a Black student group. Because of his efforts, CCNY offered its first course in African-American history. They also hired their first Black teacher, Dr. Max Yergan.

Louis was a strong speaker. He talked about racial injustice, the dangers of fascism, and problems for young people during the Great Depression. After college, he studied law for a year at St. John's University School of Law.

Early Activism in New York

In the mid-1930s, Louis joined protests in Harlem. These protests were against Italy's invasion of Ethiopia. He also spoke out about the unfair treatment of the Scottsboro Boys. During this time, he joined the Young Communist League and the Communist Party USA. This party was known for fighting against racism and segregation.

In 1939, Louis joined the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC). He became its organizational secretary in 1941. In 1939, he traveled south with historian Herbert Aptheker. They worked to help tobacco workers join a union. They also shared booklets about Black history and resistance.

In 1940, Louis ran for the New York State Assembly but did not win. In 1941, he married Dorothy Challenor, a Black youth activist. They moved to Birmingham, Alabama, to fight segregation and organize Black youth. Louis found that Black youth trusted organizers from Black groups more than from white groups. He and other SNYC men shared household chores and raising children.

In October 1941, Louis became an editor for the SNYC magazine, Cavalcade. The magazine focused on the challenges faced by Black people in the South.

Fighting for Rights in Alabama

In 1942, Louis joined the SNYC team in Birmingham, Alabama. He worked on getting Black people the right to vote. He also helped plan Black cultural events. He taught local activists about the worldwide anti-colonial movement. He believed World War II could help people of color gain freedom. He helped start SNYC groups at Black colleges in the South.

In May 1942, Louis and Esther Cooper led a SNYC group to Washington, D.C.. They met with government officials. They wanted to help Black youth join the war effort. SNYC worked to end segregation in the military and get Black workers defense jobs. They also fought to remove the poll tax, which stopped Black people from voting. Louis spoke at a voting rights rally in New Orleans in 1943.

In 1942, Louis presented ideas for SNYC. These included:

- Starting new groups in Alabama, Tennessee, and Louisiana.

- Creating more youth centers in cities like New Orleans.

- Forming groups on college campuses.

- Campaigns to get Black youth into flying services, promote voting, and create war industry jobs.

All his ideas were approved.

Because of SNYC's work, Birmingham opened its first swimming pool for Black people. It was still segregated, though. After World War II, Louis worked hard to register Black veterans to vote. He also fought to end the poll tax. In 1946, he led Black veterans on marches in Birmingham. They demanded the right to vote, which was often denied to Black people in the South.

In 1944, Louis was a leader of the Association of Young Writers and Artists (AYWA). This group helped Black youth get involved in the arts. It aimed to show how culture connects to society. Louis even offered awards for creative works inspired by the novel Freedom Road.

In 1946, Louis helped create a Leadership Training School in Irmo, South Carolina. This school taught union workers, teachers, and students how to start SNYC groups. The Southern Youth Legislature, organized by SNYC, brought together over 1500 delegates. Louis urged them to "make war on white supremacy."

Also in 1946, Louis wrote a pamphlet called Smash the Chains. It shared stories of discrimination against Black men in the South. It also included a letter from activist James E. Jackson. The pamphlet encouraged people to join SNYC.

Louis also helped restart an Alabama chapter of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. In 1942, he attended a conference in Nashville. To avoid segregation rules at the hotel, he pretended to be from India.

In 1947, he became a founding board member of the Southern Conference Educational Fund.

Louis faced trouble from the police in Birmingham. The police commissioner was Bull Connor. Connor was known for using dogs and fire hoses against Black children in 1963. Once, Connor arrested Louis for sitting with a white friend in a Black-only restaurant.

In 1947, Louis was part of a SNYC group that met with U.S. Senator Glen Taylor in Washington, D.C. Senator Taylor later joined SNYC's 1948 convention. He even argued with police to enter through the "Blacks only" door.

In 1948, Birmingham police took Louis to Connor's office. Connor threatened Louis and tried to stop the SNYC convention. Louis sent a telegram to President Truman's Attorney General, Tom C. Clark. He explained that Birmingham officials were trying to stop their meeting. But no help came from Washington.

In 1948, Louis helped with the Progressive Party's presidential campaign for Henry A. Wallace. Louis was a co-director for Wallace's efforts in the South. He traveled with Wallace and saw the violence aimed at the candidate. Louis even influenced Wallace's speeches, helping him remember to mention important Black figures like George Washington Carver.

Louis also pushed for a federal investigation into the murder of Samuel Bacon in Mississippi. But during this time, SNYC lost support due to political pressure. The Burnhams stayed in Birmingham until the SNYC office closed in 1949.

The Burnhams had two daughters in Birmingham: Claudia (1943) and Margaret (1944). Their daughter Linda was born in Brooklyn in 1948. Their son Charles was born in Brooklyn in 1950. Many SNYC members moved to Brooklyn around this time. They formed a close community, supporting each other during the Red Scare.

Freedom Newspaper and Later Work

In Brooklyn, Louis helped start a monthly newspaper called Freedom in 1950. It was a project by Paul Robeson. Louis was the managing editor. His wife, Dorothy, said he wanted to share "the story of the people who were active in the movement and who were being persecuted." The newspaper ran from November 1950 to August 1955.

In the first issue, Louis wrote an article defending people who fought for peace, good jobs, and equality for Black people. He also focused on the worldwide fight against colonialism. He wrote that "the colored people everywhere are conducting their struggles for full human equality."

Louis also supported Paul Robeson in getting his passport back. He wrote that it was "shameful" that Robeson was treated badly at home. Louis also helped prepare Robeson's songs and messages for peace conferences.

Louis hired Lorraine Hansberry in 1951 when she was 20. She later became a famous playwright. Louis encouraged her writing.

In 1951, Louis signed a petition called We Charge Genocide. This petition asked the United Nations for help against crimes committed by the U.S. government against Black people. He also helped organize an event to celebrate the first volume of Aptheker's Documentary History of the Negro People.

From 1957 to 1960, Louis wrote for the National Guardian newspaper. He was the associate editor for civil rights. He reported from the South, including Little Rock, and other cities. He talked to people on the streets and in barbershops to understand their views. He noticed a new confidence among Black people.

In 1959, Louis was elected to the National Committee of the Communist Party USA.

Near the end of his life, Louis and other SNYC friends planned a Black literary and political magazine. Louis was supposed to be the editor. But he had a heart attack and died on February 12, 1960. He was giving a lecture on "Emerging Africa and the Negro People's Fight for Freedom." He was 44 years old. He told the audience, "Tomorrow's new world beckons. Tomorrow belongs to us."

He was survived by his wife and four children. Many important figures spoke at his memorial service. W. E. B. Du Bois helped raise money for Louis's children's education. The National Guardian reprinted his last column, "Not New Ground, But Rights Once Dearly Won."

After Louis's death, his friends continued his dream of the magazine. This led to the creation of the quarterly journal Freedomways.

Louis Burnham's Family

Louis's wife, Dorothy Burnham, was also a strong activist. She continued to fight for social justice throughout her life. She worked for public education, civil rights, and women's rights. She also served on the board of Freedomways and wrote for it. She became a biology professor at Hostos Community College and City University of New York. She celebrated her 107th birthday in 2023.

Their oldest daughter was Claudia Burnham. Their daughter Margaret Burnham is a law professor and racial justice activist. She was also a judge. Their daughter Linda Burnham is a journalist and women's rights activist. Their son Charles Burnham is a violinist.

See Also

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |