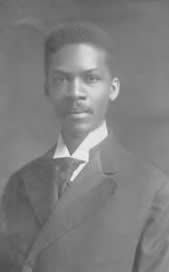

Louis George Gregory facts for kids

Louis George Gregory was an important American member of the Baháʼí Faith. He was born on June 6, 1874, in Charleston, South Carolina, and passed away on July 30, 1951, in Eliot, Maine. He dedicated his life to spreading the Baháʼí teachings, especially in the United States and other parts of the world. He traveled a lot, particularly in the Southern states, to share the message of the faith.

In 1922, Louis Gregory made history as the first African American to be elected to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada. This was a nine-member group that guided the Baháʼí community. He was re-elected many times, inspiring many followers. He also worked to introduce the faith in Central and South America. After he passed away in 1951, Shoghi Effendi, who was the head of the Baháʼí Faith at the time, named him a Hand of the Cause. This is the highest appointed position in the Baháʼí Faith.

Contents

Louis Gregory's Early Life

Louis George was born in Charleston on June 6, 1874. His parents, Ebenezer F. and Mary Elizabeth George, were African Americans who had been enslaved but became free during the Civil War. His mother, Mary Elizabeth, was of mixed race. Her mother was an enslaved African woman named Mary Bacot, and her father was a white plantation owner named George Washington Dargan.

When Louis was four years old, his father, Ebenezer, died. Louis and his mother then moved in with his paternal grandfather, who was a successful blacksmith.

In 1881, Louis's mother married George Gregory. George Gregory was the only free African American from Charleston to join the Union Army during the Civil War. He became a 1st Sergeant in the 104th United States Colored Troops (USCT). After the war, people respectfully called him Colonel Gregory, and his family received a Civil War pension. At this time, Louis George took his stepfather's last name, becoming Louis George Gregory. Because of his stepfather's military connections, Louis had the chance to meet and become friends with the children of white Army officers who visited their home.

George Gregory was also a community leader. He played an important role in the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, which included both Black and white members. When he died in 1929, the Union asked all its members to attend his funeral. About 1,000 people of both races came to Monrovia Union Cemetery, where George and Mary Elizabeth's headstones are still standing.

During his elementary school years, Louis Gregory attended the Avery Institute. This was the first public school in Charleston that allowed both African American and white children to attend. Louis's mother, Mary Elizabeth, had lost many babies, and she passed away in 1891, shortly after giving birth to another infant who also died. Louis's older brother, Theodore, died the same year. Despite these losses, Louis Gregory graduated from the Avery Institute. He gave a graduation speech titled, "Thou Shalt Not Live For Thyself Alone." Today, the Avery Institute honors Gregory by displaying his portrait in one of its preserved classrooms.

Louis gained a stepbrother, Harrison Gregory, when his stepfather married Lauretta Gregory, a widow. Lauretta's first husband, Louis Noisette, was a Civil War veteran who had died while she was pregnant with Harrison. The Noisette family had become well-known in Charleston after moving there from Saint-Domingue (now Haiti).

University and Becoming a Professional

Louis Gregory's stepfather generously paid for his first year at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where Louis studied English literature. Louis used the tailoring skills his mother had taught him to earn money for the rest of his bachelor's degree. Since there were no law schools in the South that would accept him, he went on to Howard University in Washington, D.C.. Howard was one of the few universities that accepted Black graduate students for law. He earned his law degree (LL.B.) in the spring of 1902.

After passing the bar exam, he opened a law office in Washington D.C. with another young lawyer, James A. Cobb. This partnership ended in 1906 when Gregory began working for the United States Department of the Treasury. In 1904, Gregory supported a committee celebrating Booker T. Washington. In 1906, he served as vice president of the Howard University Law School Alumni association. Gregory was interested in the Niagara Movement and was active in the Bethel Literary and Historical Society. This was an organization for Black people that discussed important issues of the day. He was elected vice president in 1907 and president in 1909. During this time, Gregory was also mentioned in newspapers because of racist incidents he faced.

Louis Gregory's Baháʼí Journey

Discovering the Religion

While working at the Treasury Department, Gregory met Thomas H. Gibbs, and they became close friends. Gibbs, though not a Baháʼí himself, told Gregory about the religion. In 1907, Gregory attended a lecture by Lua Getsinger, a leading Baháʼí. At this meeting, he met Pauline Hannen and her husband, who invited him to many other meetings over the next few years. Gregory was deeply impressed by the Hannens' kindness and the Baháʼí teachings, especially after feeling disappointed with Christianity. He read early Baháʼí writings, including The Hidden Words.

Meetings were also held among poorer communities, and the Baháʼí way of understanding Christian scriptures and prophecies greatly affected him. It offered a new way to think about how society could be improved. In 1909, while the Hannens went on a pilgrimage to visit ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, the head of the religion, in Palestine, Gregory left the Treasury Department and started his own law practice in Washington D.C. When the Hannens returned, Gregory again started attending Baháʼí meetings. The Baháʼí community in D.C. was growing and holding more and more meetings, especially integrated ones with both Black and white members. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also began to send messages, either in letters or through pilgrims, encouraging integration.

On July 23, 1909, Gregory wrote to the Hannens, confirming his acceptance of the Baháʼí Faith:

It comes to me that I have never taken occasion to thank you specifically for all your kindness and patience, which finally culminated in my acceptance of the great truths of the Baháʼí Revelation. It has given me an entirely new conception of Christianity and of all religion, and with it my whole nature seems changed for the better...It is a sane and practical religion, which meets all the varying needs of life, and I hope I shall ever regard it as a priceless possession.

First Steps as a Baháʼí

After becoming a Baháʼí, Gregory began organizing meetings for the religion. He even held one under the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, where he had been president. He also wrote to ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, who replied that he had high hopes for Gregory in improving race relations. The Hannens asked Gregory to attend organizational meetings to help plan for the religion's growth. These meetings helped make integration a reality for some Baháʼís, while for others, it was a challenge they had to work to overcome.

In November 1909, Gregory received a letter from ʻAbdu'l-Bahá that said:

I hope that thou mayest become… the means whereby the white and colored people shall close their eyes to racial differences and behold the reality of humanity, that is the universal truth which is the oneness of the kingdom of the human race…. Rely as much as thou canst on the True One, and be thou resigned to the Will of God, so that like unto a candle thou mayest be enkindled in the world of humanity and like unto a star thou mayest shine and gleam from the Horizon of Reality and become the cause of the guidance of both races.

In 1910, Gregory stopped working as a lawyer. He began a long period of service, holding meetings, traveling for the religion, and writing and lecturing about racial unity. At first, some meetings were held separately for different races. However, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá made it clear that the community should move towards integrated meetings. The fact that upper-class white Baháʼís took steps towards integration confirmed to Gregory the power of the religion. Gregory, still president of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, arranged for several Baháʼís to give presentations to the group.

Gregory started an important trip through the Southern states. He visited Richmond, Virginia; Durham and other places in North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina, his hometown; and Macon, Georgia. In these cities, he shared information about the Baháʼí Faith. In Charleston, he gave talks at the Carpenter's Union Hall. He met a priest who had learned about the religion at Green Acre in Maine. In Charleston, Alonzo Twine, an African-American lawyer, became the first known Baháʼí of South Carolina.

Gregory became more involved in the early Baháʼí administration. In February 1911, he was elected to Washington's Working Committee of the Baháʼí Assembly, becoming the first African American to hold this position. In April 1911, Gregory served as an officer for Harriet Gibbs Marshall's Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression. The school was advertised in several cities, especially in publications for Black communities.

His Pilgrimage

In late 1910, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá invited Gregory to go on a pilgrimage. Gregory sailed from New York City on March 25, 1911. He traveled across Europe to Palestine and Egypt. In Palestine, Gregory met with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and visited the holy places of the Baháʼí Faith, including the Shrine of Baháʼu'lláh and the Shrine of the Báb. In Egypt, he met Shoghi Effendi. While in the Middle East, he discussed the issue of race in the United States with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and other pilgrims. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá taught that there was no difference between the races. During this time, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá encouraged Gregory and Louisa Mathew, a white English pilgrim, to get to know each other.

After leaving Egypt, Gregory traveled to Germany, where he spoke at several gatherings for Baháʼís and their friends. When he returned to the United States, he continued to travel, mainly in the southern states, to talk about the Baháʼí Faith. He held his first public meeting about the religion after his return. He also published an article in the Washington Bee in November, inspired by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's visit to Britain that month. He was elected to a Washington Baháʼí working committee.

1912: A Significant Year

In April 1912, Gregory was elected to the national Baháʼí "executive board." He helped during ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's visit to the United States. During this visit, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá repeatedly emphasized the Baháʼí Faith's teaching of the oneness of humanity. He used beautiful descriptions, sometimes using black-colored references, to talk about beauty and goodness. You can learn more about this in ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá thanked Gregory for his efforts on several occasions. One notable time was on April 23, 1912. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá attended several events that day. First, he spoke at Howard University to over 1,000 students, teachers, and visitors. This event was remembered in 2009. He then attended a reception hosted by the Persian and Turkish ambassadors. At the reception, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá moved the place-cards so that Gregory, who was the only African American present, could sit at the head table next to him. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also spoke at the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, where Gregory had been involved for a long time and had served as president. Later in June, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá spoke at the NAACP national convention in Chicago. This event was reported by W. E. B. Du Bois in The Crisis magazine.

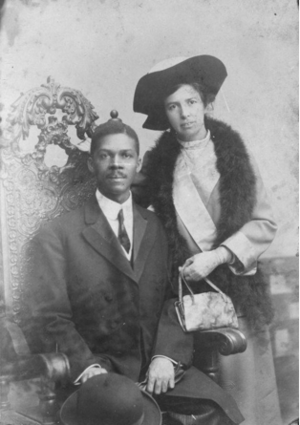

Louis Gregory and Louisa Mathew had grown closer. They married on September 27, 1912, becoming the first known Baháʼí interracial couple. When Louisa traveled with Gregory in the United States, they faced different reactions. At that time, interracial marriage was illegal or not recognized in most states.

Years of Dedicated Service

In the spring of 1916, the Washington Baháʼí community worked hard to hold only integrated meetings and create integrated institutions. That summer, they received ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's first Tablets of the Divine Plan. Joseph Hannen, who worked with Gregory on a committee, received the Tablet for the South.

By December, Gregory had traveled through 14 of the 16 Southern states mentioned in the Tablets. He mostly spoke to student audiences, which were largely segregated by law. He began a second round of travels in 1917. The NAACP started forming chapters in South Carolina in 1918. However, since 1915, the KKK had seen a revival, and there was other social unrest due to tensions from World War I, which the U.S. entered in 1917. Gregory knew many of the early organizers of the NAACP.

In 1919, the remaining letters from ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived. He used the example of St. Gregory the Illuminator as a model for spreading the religion. Hannen and Gregory were then elected to a committee focused on the American South. Gregory focused on two main approaches: presenting the religion's teachings on race to social leaders and to the general public. He started his next major trip from 1919 to 1921, often with Roy Williams, an African-American Baháʼí from New York City. In 1920, a pilgrim returned from seeing ʻAbdu'l-Bahá with the idea of starting conferences on race issues called "Race Amity Conferences." Gregory helped plan how to begin these. The first one was held in May 1921 in Washington D.C.

Gregory met Josiah Morse from the University of South Carolina. Starting in the 1930s, several Baháʼí speakers began to appear at university events. Gregory became friends with Samuel Chiles Mitchell, who was president of the University of South Carolina from 1909 to 1913. Mitchell shared that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's views, which he heard at the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, influenced his work for racial equality into the 1930s.

Gregory also faced increasing opposition. In January 1921, he spoke in Columbia, South Carolina. Some African-American ministers warned people against his message and religion. However, others invited Gregory to speak to their congregations.

In 1922, Gregory was the first African American to be elected to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada. He was repeatedly elected to this nine-person body in 1924, 1927, 1932, 1934, and 1946. His letters and activities were often covered in newspapers in the U.S. and other countries.

In 1924, Gregory toured the country, giving many speeches. He often appeared with Alain LeRoy Locke, who was also a Baháʼí and an important African-American thinker during the Harlem Renaissance.

Gregory's father passed away in 1929. He had praised Gregory for his work, marriage, and beliefs. Although his father never became a Baháʼí, he was known to hand out Gregory's pamphlets. About one thousand people attended the funeral, where Gregory read Baháʼí prayers.

In the 1930s, Gregory worked on the religion's growth both within the U.S. and internationally. In December 1931, he helped start a Baháʼí study class in Atlanta. He lived in Nashville, Tennessee for several months, working with people from Fisk University who were interested in the faith. Some of these individuals helped establish Nashville's first local Spiritual Assembly.

In response to Shoghi Effendi's call to achieve the goals of the Tablets of the Divine Plan, the U.S. Baháʼí community created a plan of action. Gregory and his wife Louisa traveled to and lived in Haiti in 1934 to promote the religion. However, the Haitian government asked them to leave within a few months, as Catholicism was the main established religion there.

In 1940, the Atlanta Baháʼí community faced challenges regarding integrated meetings. Gregory was among those assigned to help resolve the situation in favor of integrated meetings. In early 1942, Gregory spoke at several Black schools and colleges in West Virginia, Virginia, and the Carolinas. He also served on the first "assembly development" committee, which focused on creating materials to help the religion grow in Central and South America. In 1944, Gregory was on the planning committee for the "All-America Convention," which brought together attendees from all Baháʼí national communities. He wrote the convention report for the national Baháʼí journal, Baháʼí News. He traveled from the winter of 1944 through 1945 among five Southern states.

Newspapers covered the Race Amity conventions organized by Baháʼís from the 1920s through the 1950s. These conventions took place during a time of ongoing racial issues and violence in the U.S.

Later Years

In December 1948, Gregory suffered a stroke while returning from a friend's funeral. His wife's health was also declining, and the couple began to stay closer to home. They lived at Green Acre Baháʼí School in Eliot, Maine. Gregory continued to write letters to U.S. District Court Judge Julius Waties Waring and his wife in 1950-51. Judge Waring was involved in the important civil rights case Briggs v. Elliott.

Louis Gregory passed away at the age of seventy-seven on July 30, 1951. He is buried in a cemetery near the Green Acre Baháʼí school. After his passing, his wife Louisa found comfort with the Noisette family in New York.

Legacy and Honors

- When Louis Gregory died, Shoghi Effendi, who was the head of the Baháʼí Faith, sent a telegram to the American Baháʼí community. He wrote:

Profoundly deplore grievous loss of dearly beloved, noble-minded, golden-hearted Louis Gregory, pride and example to the Negro adherents of the Faith. Keenly feel loss of one so loved, admired and trusted by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Deserves rank of first Hand of the Cause of his race. Rising Baháʼí generation in African continent will glory in his memory and emulate his example. Advise hold memorial gathering in Temple in token recognition of his unique position, outstanding services.

- Gregory was among Shoghi Effendi's first appointments to the special rank of Hands of the Cause. Memorial services for Gregory were among the first events held by new Baháʼís and converts in Uganda.

- The Baháʼí radio station WLGI is named after Gregory: it is called the Louis Gregory Institute.

- The Louis Gregory Preschool in Lesotho, Africa, is also named for him.

- The Louis G. Gregory Bahá'í Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, is a memorial dedicated to his life and work.