Louise Brooks facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louise Brooks

|

|

|---|---|

Brooks c. 1926

|

|

| Born |

Mary Louise Brooks

November 14, 1906 Cherryvale, Kansas, U.S.

|

| Died | August 8, 1985 (aged 78) Rochester, New York, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Holy Sepulchre Cemetery (Rochester, New York) |

| Other names | Lulu, Brooksie, The Girl in the Black Helmet |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1925–1938 |

| Known for | Pandora's Box (1929) Diary of a Lost Girl (1929) |

| Spouse(s) |

A. Edward Sutherland

(m. 1926; div. 1928)Deering Davis

(m. 1933; div. 1938) |

Mary Louise Brooks (born November 14, 1906 – died August 8, 1985) was an American film actress and dancer. She was famous in the 1920s and 1930s. Today, she is seen as a symbol of the Jazz Age and the "flapper" style. This is partly because of her short, stylish bob hairstyle, which became very popular.

Louise Brooks started her career as a dancer at age 15. She toured with the Denishawn School of Dancing. Later, she danced in famous shows like George White's Scandals and the Ziegfeld Follies in New York City. A movie producer named Walter Wanger noticed her. He signed her to a five-year contract with Paramount Pictures. She appeared in several films, including Beggars of Life (1928).

Brooks was not happy with her roles in Hollywood. In 1929, she went to Germany. There, she starred in three movies that made her an international star: Pandora's Box (1929), Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), and Miss Europe (1930). The first two were directed by G. W. Pabst. By 1938, she had acted in 17 silent films and 8 sound films. After she stopped acting, she faced money problems. In the 1950s, her films were rediscovered by movie fans. Louise Brooks then started writing articles about her film career. Her book, Lulu in Hollywood, was published in 1982. She passed away three years later at age 78.

Contents

Early Life and Dance Career

Louise Brooks was born in Cherryvale, Kansas. Her father, Leonard Porter Brooks, was a lawyer. Her mother, Myra Rude, was a talented pianist. She taught her children to love books and music.

In 1919, her family moved to Independence, Kansas. The next year, they moved to Wichita.

Brooks began dancing professionally at age 15. She joined the Denishawn School of Dancing in Los Angeles in 1922. This dance company traveled the world. Brooks performed in London and Paris. She even had a starring role with Ted Shawn. However, she was later dismissed from the company.

After leaving Denishawn, Brooks quickly found new work. She became a chorus girl and then a dancer in the 1925 Ziegfeld Follies in New York City. While dancing in the Follies, she caught the eye of Walter Wanger. He was a producer at Paramount Pictures. In 1925, Wanger signed her to a five-year movie contract.

Movie Career

Early Paramount Films

Louise Brooks first appeared on screen in 1925. It was an uncredited role in The Street of Forgotten Men. Soon, she was playing lead roles in silent comedies. She starred with actors like Adolphe Menjou and W. C. Fields.

After her small roles in 1925, both Paramount and MGM offered her contracts. She chose Paramount. In 1928, her role in A Girl in Every Port made her popular in Europe. Her unique bob haircut also became a trend. Many women copied her hairstyle.

After filming Beggars Of Life (1928), Brooks started The Canary Murder Case (1929). She was unhappy with Hollywood and wanted a raise. When she didn't get it, she left Paramount. She went to Berlin, Germany, to work with director G. W. Pabst. This decision later became very important for her career. It made her a silent film legend.

When she returned from Germany, she refused to do sound retakes for The Canary Murder Case. This made Paramount angry. The studio claimed her voice was not good for sound films. Another actress was hired to dub her voice.

European Success

Brooks traveled to Europe. The German film industry was a major rival to Hollywood. In Weimar Germany, she starred in the 1929 silent film Pandora's Box. It was directed by Pabst. He was a leading director known for his elegant films. Brooks played the main character, Lulu.

Her performance in Pandora's Box made her a star. Pabst chose Brooks over more famous actresses. He saw something special in her. Brooks was 22 years old when she made the film.

When people first saw Brooks's German films, her acting style was new to them. She used a natural, subtle style. At that time, actors usually used big body movements and facial expressions. Brooks understood that close-ups in movies meant less exaggeration was needed. She believed acting was about showing "thought and soul." This style is common today, but it was surprising then. Film critic Roger Ebert later said Brooks became "one of the most modern and effective of actors."

Her roles in Pabst's two films made Brooks famous around the world. After these successes, she made one more European film. It was a French film called Miss Europe (1930).

Return to America

Brooks returned to New York in December 1929. In 1931, she was cast in two films: God's Gift to Women and It Pays to Advertise. However, critics did not pay much attention to her performances. She had trouble finding more roles because of her earlier decision to leave Paramount.

Brooks tried to make a comeback in 1936. She had a small part in a Western film called Empty Saddles. In 1937, she got a small role in King of Gamblers. Sadly, her scenes were later removed from the movie.

Brooks made two more films. Her last film was the 1938 Western Overland Stage Raiders. She played the main female role opposite John Wayne. In this film, she had long hair, making her look very different from her famous "Lulu" character. Critics did not give her much attention for this role.

Life After Film

Financial Challenges

By 1940, Brooks's acting career had mostly ended. She lived in a small apartment in West Hollywood. She worked as a copywriter for a magazine. Soon, she lost that job and struggled to find steady work.

She tried to run a dance studio, but it was not successful. She then moved back to New York City. She worked briefly as a radio actor and a gossip columnist. Later, she worked as a salesgirl at a Saks Fifth Avenue store.

Rediscovery and Writing

In 1955, French film historians rediscovered Brooks's films. They praised her as an amazing actress. This led to a Louise Brooks film festival in 1957. It helped bring her back into the public eye in her home country.

James Card, a film curator, found Brooks living quietly in New York City. He convinced her to move to Rochester, New York, in 1956. There, she could study films and write about her career. With Card's help, she became a respected film writer. Her collection of writings, Lulu in Hollywood, was published in 1982. It is still considered a very important book about film.

In her later years, Brooks rarely gave interviews. However, she had special friendships with film historians. She was interviewed for several documentaries, including Memories of Berlin: The Twilight of Weimar Culture (1976) and Hollywood (1980). In 1979, writer Kenneth Tynan wrote an essay about her called "The Girl in the Black Helmet." This name referred to her famous bobbed hair.

Death

Louise Brooks passed away on August 8, 1985. She was 78 years old. She had been suffering from osteoarthritis and emphysema for many years. She died from a heart attack in her apartment in Rochester, New York.

Personal Life

In 1926, Brooks married Eddie Sutherland, a film director. By 1927, she became close with George Preston Marshall. He owned a chain of laundries and later owned the Washington Redskins football team. Their meeting was very important in her life.

Brooks and George Preston Marshall had an on-again, off-again relationship for several years.

In 1933, she married Deering Davis, a millionaire from Chicago. However, she left him after only five months. They officially divorced in 1938.

In her later years, Brooks said that she had never truly loved anyone.

In 1953, Brooks became a Roman Catholic. She left the church in 1964.

Filmography

Some of Louise Brooks's films are now lost. However, her most important films still exist. These include Pandora's Box and Diary of a Lost Girl. These films are available on DVD.

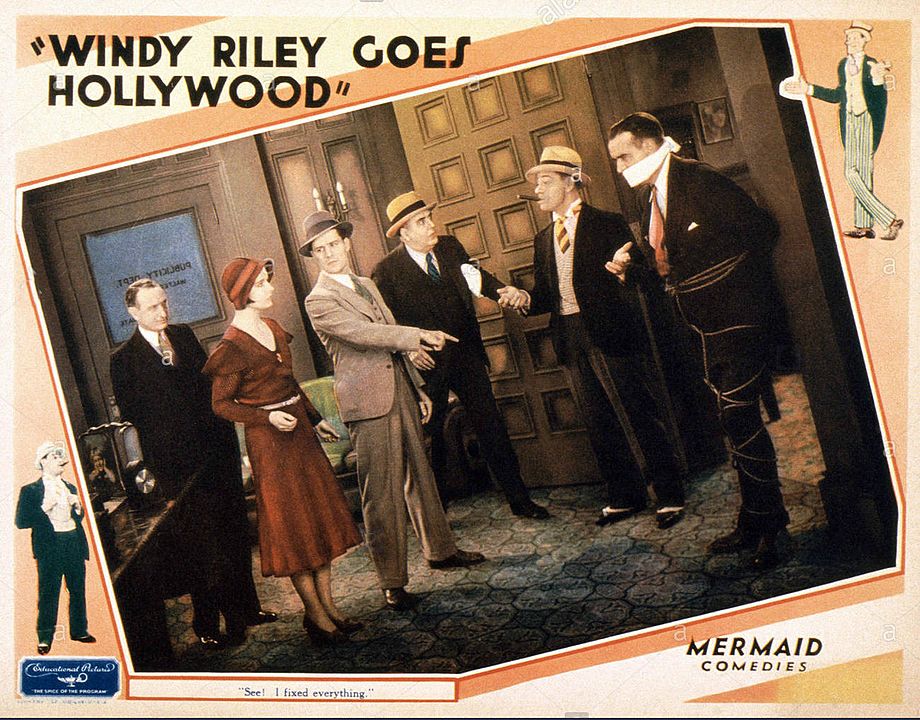

Her short film Windy Riley Goes Hollywood was included on the DVD release of Diary of a Lost Girl. Her final film, Overland Stage Raiders, was released on VHS and later on DVD.

| Year | Title | Role | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | The Street of Forgotten Men | A Moll | Herbert Brenon | Incomplete (missing part of the film) |

| 1926 | The American Venus | Miss Bayport | Frank Tuttle | Lost film. Some small pieces have been found. |

| 1926 | A Social Celebrity | Kitty Laverne | Malcolm St. Clair | Lost film |

| 1926 | It's the Old Army Game | Mildred Marshall | A. Edward Sutherland | |

| 1926 | The Show Off | Clara | Malcolm St. Clair | |

| 1926 | Just Another Blonde | Diana O'Sullivan | Alfred Santell | Only parts of the film survive. |

| 1926 | Love 'Em and Leave 'Em | Janie Walsh | Frank Tuttle | |

| 1927 | Evening Clothes | Fox Trot | Luther Reed | Lost film |

| 1927 | Rolled Stockings | Carol Fleming | Richard Rosson | Lost film |

| 1927 | Now We're in the Air | Griselle/Grisette | Frank R. Strayer | A 23-minute part was found in 2016. |

| 1927 | The City Gone Wild | Snuggles Joy | James Cruze | Lost film |

| 1928 | A Girl in Every Port | Marie, Girl in France | Howard Hawks | |

| 1928 | Beggars of Life | The Girl (Nancy) | William A. Wellman | The sound version is lost; only the silent version remains. |

| 1929 | The Canary Murder Case | Margaret Odell | Malcolm St. Clair | Both silent and sound versions exist. |

| 1929 | Pandora's Box | Lulu | G. W. Pabst | |

| 1929 | Diary of a Lost Girl | Thymian | G. W. Pabst | |

| 1930 | Miss Europe | Lucienne Garnier | Augusto Genina | Also known as Prix de Beauté. Brooks's first sound film. Both silent and sound versions exist. |

| 1931 | It Pays to Advertise | Thelma Temple | Frank Tuttle | |

| 1931 | God's Gift to Women | Florine | Michael Curtiz | |

| 1931 | Windy Riley Goes Hollywood | Betty Grey | Roscoe Arbuckle | |

| 1936 | Empty Saddles | "Boots" Boone | Lesley Selander | |

| 1937 | When You're in Love | Chorus Girl | Robert Riskin | Uncredited role (not listed in the credits). |

| 1937 | King of Gamblers | Joyce Beaton | Robert Florey | Her scenes were removed from the final film. |

| 1938 | Overland Stage Raiders | Beth Hoyt | George Sherman |

See also

In Spanish: Louise Brooks para niños

In Spanish: Louise Brooks para niños