Lullingstone Roman Villa facts for kids

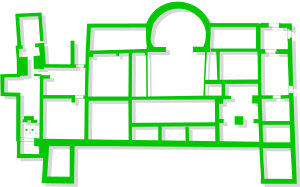

Quick facts for kids Lullingstone Roman Villa |

|

|---|---|

The enclosed interior of Lullingstone Villa

|

|

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Romano-British Villa |

| Location | Lullingstone grid reference TQ53016508 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°21′50″N 0°11′47″E / 51.3640°N 0.1964°E |

| Construction started | 1st century |

| Demolished | 5th century |

The Lullingstone Roman Villa is an ancient Roman house built in Britain when the Roman Empire ruled the land. You can find it near Lullingstone village in Kent, south-eastern England. This villa is special because it's one of several Roman villas located in the Darent Valley.

Built around 80–90 AD, this large house was expanded many times. People lived there for centuries until a big fire destroyed it in the 4th or 5th century. The people who lived here were likely wealthy Romans or native Britons who had adopted Roman ways of life.

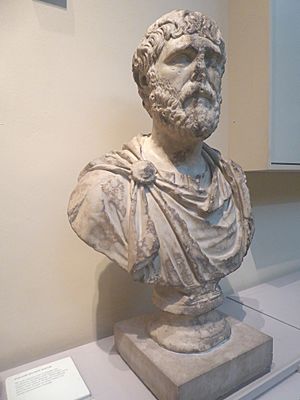

Archaeologists found clues suggesting that around 150 AD, the villa became much bigger. It might have even been a country home for the Roman governors of Britain! Two marble statues found in the cellar might be of Pertinax, a governor in 185–186 AD, and his father-in-law.

In the 4th century, a room that was already used for religious purposes was changed into a Christian chapel. This is one of the earliest known Christian chapels in the British Isles! Later, during the Anglo-Saxon period, parts of a Roman temple on the site were used to build a Christian chapel, which was still there during the Norman Conquest.

Besides the chapel and beautiful floor mosaics, other amazing art was found here. These include the Lullingstone Victory Gem and the marble statues.

Discovering Lullingstone Roman Villa

Building the Villa

The first part of the Lullingstone Roman Villa was built around 82 AD. It was in an area with other villas and close to Watling Street. This was an important Roman road that connected major Roman towns like London, Rochester, Canterbury, and the port of Richborough.

Growing Over Time

Around 150 AD, the villa got bigger. A heated bath area with a hypocaust (an ancient underfloor heating system) was added. After being empty for almost 100 years, it was rebuilt around 290 AD. The two marble statues from the 2nd century, found in the cellar, might show the villa's owners. Some think they could be Pertinax, who was governor of Britain in 185–186 AD, and his father. Pertinax later became a Roman emperor!

In the 3rd century, the heating system got a larger furnace, and the bath area was expanded. A temple-mausoleum (a tomb with a temple) and a large granary (a building for storing grain) were also built. By the 4th century, the dining room had amazing mosaic floors. One mosaic shows the god Jupiter (or Zeus) as a bull, taking Europa away. Another shows Bellerophon fighting the Chimera, a mythical monster.

Fire and Finding It Again

Early in the 5th century, a fire destroyed the villa. It was left empty and forgotten for many centuries.

The first hint of the villa was found in 1750. Workers digging fence posts for a deer park accidentally dug through a mosaic floor. People noted the discovery, but no one dug further.

It wasn't until 1939 that the villa's ruins were truly rediscovered. E. Greensfield and E. Birchenough saw Roman walls and mosaic pieces under a fallen tree. From 1949 to 1961, archaeologists finally excavated the site. The ruins had been untouched since the fire!

In the 1960s, English Heritage took over the site. They built a special cover to protect the ruins and opened them to the public. The building started leaking later, so a big renovation project happened from 2006 to 2008. This allowed the amazing items found at Lullingstone to be safely displayed.

Life at the Villa Through the Centuries

1st Century AD: Early Days

During the first digs in the 1950s, archaeologists found pottery from different centuries. The oldest pieces were from the 1st century AD. These pottery shards were handmade and showed signs of "Belgic culture," from a group of people living in Britain before the Romans.

2nd Century AD: Growth and Baths

The villa grew a lot during the 2nd century. The Bath Room and Basement Room might have been built during this time. Evidence from different layers of clay suggests that the stairs to the basement were built then, not later as first thought.

3rd Century AD: Abandonment and Return

Based on pottery, the villa seems to have been empty for the first half of the 3rd century AD. Coins found show that people moved back in during the second half of the 3rd century. This was when the pagan shrine and other Christian rooms were built. Also, important outside buildings like the granary and temple were added.

4th Century AD: Big Changes and Fire

The 4th century was busy for the villa. Many renovations took place, and this is probably when the fire happened. The beautiful mosaic floor in Room 5 was designed then. Archaeologists dated this floor using coins of Constantine II that were accidentally mixed into the concrete.

After the Romans: A Burial Ground?

After the villa's destruction, there was no sign of anyone living there until medieval times. However, English Heritage found a "hanging bowl" and other Anglo-Saxon pottery pieces. This suggests the site might have been used as a burial ground in early Anglo-Saxon Britain.

Rooms of the Villa

The Dining Room

The dining room, also called a triclinium, was in the middle of the main building. It was the largest room on the western side and connected other rooms through a big porch. This room was beautifully decorated with two large mosaic floors from the mid-4th century.

One mosaic shows the god Jupiter, disguised as a bull, carrying off Princess Europa. The other shows Bellerophon killing the Chimera, a monster with a lion's head, goat's body, and snake's tail. This mosaic also has busts of the four seasons in its corners. Smaller images of hearts, crosses, and swastikas surrounded these mosaics. Some experts think these artworks were meant to protect the villa from bad luck. The room was large enough for a couch where three people could relax and enjoy the mosaics.

The Bath Wing

The Bath Wing, or bath area, was likely built in the 2nd century. It was used and updated throughout the villa's history. After the villa was empty for a while, the Bath Wing was renovated. During the first excavations, a "combustion chamber" was found here. This chamber, filled with chalk and burned charcoal, was probably used to heat the baths.

The Basement Room

Archaeologists believe the Basement Room had several uses, possibly even as a garden room. Its walls were brightly decorated with orange, red, and green panels. The room was originally about 8 feet tall. When the villa was abandoned, many materials were taken from the walls and stairs. When people moved back in, the walls were redecorated, and new pottery was added.

When the fire destroyed the villa, parts of the mosaic and plaster from the room above fell into the Basement Room. This protected many pieces of evidence, keeping them safe until the excavations began in 1949.

Pagan Shrine and Christian Chapel

One special room in the villa was first a pagan shrine and later became a Christian chapel. This is one of the earliest Christian chapels found in Britain! There were also three or four other rooms used for Christian purposes, like an entrance room and a waiting room.

The original pagan shrine honored local water gods. You can still see a wall painting of three water nymphs in a special alcove in the room.

After the 3rd century, this alcove was covered. The room was redecorated with white plaster and red bands, and two statues of men were placed there. Some scholars think the residents started worshiping household gods and ancestors instead of the water deities.

In the 4th century, the room above the pagan shrine was changed for Christian use. It had painted plaster on the walls, showing figures of standing worshipers and a Christian Chi-rho symbol (a symbol for Christ). Some of these paintings are now in the British Museum.

English Heritage, which looks after the site, says:

The Christian house-church is a unique discovery for Roman Britain. Its wall paintings are incredibly important worldwide. They show some of the earliest evidence of Christianity in Britain and are almost one-of-a-kind. Similar examples are only found in a house-church in Dura Europus, Syria.

It's also amazing that pagan worship might have continued in the room below. We don't know if the family was trying to please both old and new gods, or if some family members held onto old beliefs while others became Christian.

The chapel's exact purpose, besides worship, isn't fully known. It might have been used for Christian ceremonies like baptisms. The large size of the Christian artwork suggests the villa's owners were not only Christians but also very wealthy.

Graves at the Villa

Around 300 AD, a Roman-Celtic temple-mausoleum (a grand tomb) was built. It held the bodies of two young people, a male and a female, in lead coffins. Sadly, the young woman's coffin was robbed long ago. But the other coffin was found untouched and is now on display at the site.

Art and Artefacts

The Victory Gem

The Victory Gem was found during the first excavations. It's a "Roman cornelian intaglio," a type of carved gemstone. These gems were usually set in rings. This one is quite large, measuring 23 by 19 by 5 millimeters, making it one of the biggest gems ever found in Britain!

Because of its size and traces of gold, experts believe the ring belonged to a very important and wealthy man. The gem shows the goddess Victory writing a message of triumph on a shield. Its artwork has Greek influences, combining features of the goddesses Nike and Aphrodite.

The Marble Busts

The two marble busts found in the Basement Room are thought to be Pertinax, who was governor in 185–186 AD, and his father, Publius Helvius Successus. These busts help us understand who might have lived in the villa in the 2nd century. One bust is believed to be from the time of Emperor Hadrian. Both are well-preserved, though the larger one was more damaged when found. Archaeologists aren't sure why they were placed in the Basement Room. It's possible that after the villa was abandoned, new residents decided to keep them for their own reasons.

See also

In Spanish: Villa romana de Lullingstone para niños

In Spanish: Villa romana de Lullingstone para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |