Ghost bat facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Macroderma gigas |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Captive specimen hanging at roost | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

|

|

| Ghost bat range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Megaderma gigas |

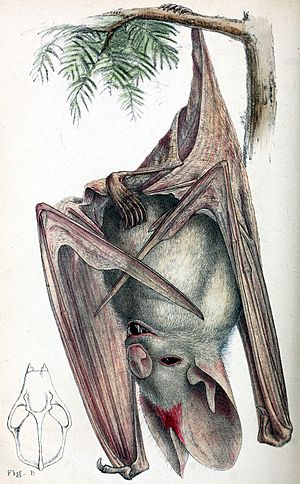

The ghost bat (Macroderma gigas) is a unique flying mammal that lives in northern Australia. It's the only Australian bat that hunts and eats large animals like birds, reptiles, and other mammals! They find their prey using amazing eyesight, sharp hearing, and a special skill called echolocation. They often wait quietly in a spot, ready to pounce.

Ghost bats have pale, almost white, wing membranes and skin. Their fur can be light or dark grey on their back and lighter on their belly. They have a noticeable, simple nose-leaf, very large ears that are joined at the bottom, and big, dark eyes. This species was first described in 1880. Since then, the areas where they live have become much smaller.

Contents

About the Ghost Bat's Name

The ghost bat belongs to a group of bats called Macroderma. This group is part of the Megadermatidae family, also known as "false vampire bats." Bats in this family have big eyes, a nose-leaf, and long ears that connect at the bottom. You can find them in southern Asia and central Africa too.

The first scientific description of the ghost bat was written in 1880 by George Edward Dobson. He studied bats from the Göttingen Museum. Dobson thought the ghost bat looked a lot like the Megaderma spasma (lesser false vampire bat). Later, a scientist named Gerrit Smith Miller put the ghost bat into a new group called Macroderma. This is how it got its current scientific name, Macroderma gigas.

The name Macroderma gigas comes from Greek words. Macros means "large" and derma means "skin," which refers to their big, partly joined ears. The word gigas means "giant," because it's the largest bat in its family.

The ghost bat was actually seen and described earlier by Gerard Krefft in 1879. He sent a specimen to the Göttingen Museum. The bat was found near the Wilson River in Queensland. An even earlier sighting was made by explorer Robert Austin in 1854 in Western Australia.

Scientists have studied the ghost bat's brain. They think it's a special link between insect-eating bats and meat-eating bats from South America. People also call them false vampires or Australian false vampire bats. The name "ghost bat" comes from their pale, almost white or light grey fur.

What Does a Ghost Bat Look Like?

The ghost bat is the biggest microbat in Australia. It's even as big as some flying foxes! Their fur is grey, from medium to dark, and sometimes very pale grey on their back. Their belly and head are whitish. Bats living near the coast tend to have darker fur. They have dark rings around their eyes. Their wing membranes and other bare skin are pale and brownish.

Their ears are very long, about 44 to 56 millimeters from the notch to the tip, and they are shaped like flutes. The inner edges of their ears are joined together for half their length. These stiff ears stay upright when the bat flies.

Other measurements for ghost bats include:

- Forearm length: 96 to 112 millimeters

- Head and body length: 98 to 120 millimeters

- Weight: 75 to 145 grams (average 105 grams)

Ghost bats have large, well-developed eyes for seeing at night. Their nose-leaf is also big and noticeable. This nose-leaf probably helps them send and receive echolocation signals to find prey, similar to how other leaf-nosed bats use their noses. A unique feature of this bat is that it has almost no tail. However, a small bone near its ankle supports the membrane at the back. Their strong jaws and sharp teeth allow them to eat many different animals, including the bones and flesh of vertebrates or the hard shells of large insects.

You can actually hear the ghost bat's voice! One sound they make is like a bird called the fairy martin, which sounds like 'dirrup dirrup'. They make this chirping sound when they are excited or before they leave their roost to hunt. They are usually quiet, but in captivity, they might squeal when fighting over food. Young bats will chirp constantly when their mother is away.

Ghost Bat Behavior and Diet

Ghost bats are active at night and rest during the day, but they don't hibernate. The size of their groups gets smaller in the Australian winter. However, their numbers increase when they gather to breed or when females form groups to have their babies.

They leave their roosts a few hours after sunset, either alone, in pairs, or in small groups. They hunt by waiting quietly, hanging from a tree, or by flying low over plants. Their big ears help them hear prey moving on the ground. Scientists have seen them hanging from trees and then dropping down to catch large locusts moving in the grass up to 20 meters away! They can also hear the echolocation signals of other small bats, which they sometimes hunt.

Ghost bats have good eyesight for a microbat, and they also use echolocation to find prey directly. They can spot birds roosting in trees. They especially like budgerigars, which they find by listening to the flock's chatter as they settle down for the night. They take the budgies to a special spot to eat them head first, leaving behind the feet and wings.

They might catch prey on the ground or take it there. They use their wings to wrap around the animal and then kill it with bites to the neck. Their sharp teeth and strong jaws can take down animals as big as a bar-shouldered dove, which can weigh up to 150 grams, though most of their prey is smaller. Bird and mammal remains are often found in their droppings. Once they catch an animal, they hold it down with their thumb claws and kill it with one bite to the neck. They eat their prey at a special feeding spot, like under a rock or in a small cave.

The false vampire bat family, including the ghost bat, eats meat. They commonly hunt insects, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles. This includes large insects, small mice, other bats, small birds, frogs, legless lizards, geckos, and snakes. While they are known as specialized meat-eaters, they will eat insects if other prey is hard to find. They eat vertebrate prey more often, usually right where they catch it. They catch other microbat species in flight, such as sheathtails, bentwings, horseshoe bats, and little cave eptesicus.

Studies show that ghost bats hunt over 50 different bird species. They prefer birds weighing less than 35 grams. Birds that roost in large groups are a big part of their diet. They even hunt a nocturnal bird called the Australian owlet-nightjar. By studying the remains of animals at their feeding spots, scientists can learn about ancient bat diets from fossils found in places like Riversleigh.

Scientists who handle ghost bats say they are surprisingly calm. Other reports confirm that ghost bats will prey on rodents caught in pitfall traps.

Where Do Ghost Bats Live?

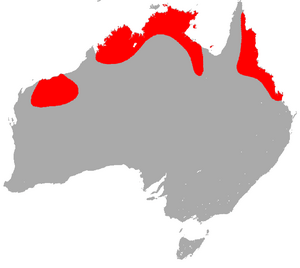

The ghost bat lives only in Australia. There are three main areas where they are found: the northern Pilbara and Kimberley regions in Western Australia, the Top End of the continent, and Queensland. Their colonies are not continuous; they usually live in small, separate groups within each region. Fossil records show that their distribution in Australia has changed over time, likely due to the continent becoming drier.

Not much is known about the ghost bat's genetics, but research shows that their populations are very distinct locally and regionally.

The southernmost record of a ghost bat was in 1854 at Mount Kenneth. A favorite limestone cave for ghost bats is near the Mitchell and Palmer rivers in Cape York. They are also found around Shoalwater Bay on the east coast.

Litchfield National Park is an important home for ghost bats and other bat species near Darwin. The largest known breeding colony of ghost bats is in an old gold mine called Kohinoor in the Top End. This mine is now used as a nursery for bats. Another famous breeding site is at Nourlangie Rock in Kakadu National Park, which is a protected area. They are also found in Mount Etna Caves NP and at Tunnel Creek, where they share caves with other bat species. Small groups have been seen along the Victoria River and at Camooweal Caves NP. In the Kimberley region, they live near rocky cliffs, gorges, or outcrops along rivers.

Ghost bats might hunt in human-made areas, but they prefer to rest during the day in caves, sheltered rock cracks, piles of boulders, or old mines. They rarely use abandoned buildings. They like places with many tunnels or rooms and several ways to get outside. Ghost bats prefer caves with multiple entrances because they are large enough for their wide wingspan and offer an escape route if they sense danger. They need several suitable spots for resting, eating, and having babies, and they move between these locations depending on the season. They are very sensitive to human disturbance, which affects where they choose to roost.

The ghost bat and the caves they lived in were well known to Indigenous Australians. They often told early explorers where to find them. Some sites were important for 'men's business,' sharing stories about the bats with young people.

Fossils of Macroderma gigas have been found at the Riversleigh World Heritage Area in Australia. This shows that the ghost bat is a modern relative of a bat lineage that goes back to at least the early Miocene epoch.

Why Ghost Bat Numbers Are Declining

The ghost bat used to live all over Australia, but now its population is much smaller and mostly found in northern areas. After its discovery, it was recorded a few more times in places like Alice Springs and the Pilbara. In 1961, surveys began to track their numbers. It became clear that they were once more widespread but were disappearing from areas where people remembered seeing them. For example, Hedley Finlayson spoke to Pitjanjarra elders who knew of the species in the Musgrave Ranges, Mann Ranges, and Tomkinson Ranges, but hadn't seen them for 40 years.

Ghost bats were once seen across central Australia. Dried remains have been found in caves in the Flinders Ranges, and skeletons have been found in coastal caves in southwest Australia. Now, their range is limited to coastal regions north of the Tropic of Capricorn.

Researchers have noticed that there's no evidence of the species in its former range. The reason for their move north, both before and after European settlement, has been studied. There are separate groups of bats in specific maternity sites, and the females in these groups have distinct genes. This suggests that these groups have been separated for a very long time. Being scattered into small populations greatly increases their risk of extinction.

It's estimated that only a few thousand ghost bats exist today. Scientists hope that their numbers will increase because more young bats are surviving, not because bats are moving from other areas. Very few national parks are actively protecting the species right now. The decline in ghost bat numbers has been linked to the spread of the cane toad (Rhinella marina). When cane toads reached areas where ghost bats lived, the bats disappeared. There's also evidence that ghost bats sometimes eat cane toads, and one deceased bat was found with a toad in its throat. This strongly suggests that the cane toad is a major reason for their rapid decline.

Ghost Bat Reproduction and Life Cycle

During the breeding season, which is from late October to early November, female bats gather in groups. Each female gives birth to a single baby. It's estimated that a ghost bat generation lasts about four years. A study showed that female bats give birth in late spring. However, only 40% of females breed in their second year, but this increases to 93% for females older than two years.

Maternity colonies are set up in large, open caves, and the mothers stay there until their young are old enough. Females have noticeable teats during this time. The baby bat can cling to its mother until its milk teeth fall out. Young bats are born in the Australian spring. They can fly after about seven weeks and are fully weaned (stop drinking milk) at 16 weeks. Like most microbats, the mother usually has only one baby. Male bats do not help raise the young. The young bat hunts with its mother until it can hunt on its own.

Ghost Bat Ecology

Other animals found with ghost bats include the black flying fox, seen at Tunnel Creek in the Kimberley. A new type of parasite, the tick Argas macrodermae, was found on ghost bats. However, for a microbat, they are surprisingly free of external parasites. The only internal parasite ever recorded in a ghost bat is a type of worm called Josefilaria mackerrasae, found in 1979.

Ghost bats have few predators. Most of their competition for food at night comes from medium-sized owls. Ghost bats will sometimes join other predators at a cave entrance where other bat species are leaving. This gathering of different meat-eaters is even more intense when young bats are emerging from their nursery. These groups can include introduced animals like cane toads, feral cats, and foxes, as well as native animals like pythons, birds of prey, quolls, and large frogs.

The bat often takes its prey to a feeding roost, where a pile of discarded remains, called a midden, forms. The discovery of a type of skink in a ghost bat's feeding roost in Queensland helped extend the known range of that skink species.

Ghost bats are vulnerable to several human-caused dangers. One major threat is barbed wire fences, which can easily tear their delicate wing membranes while they are flying. The damage from barbed wire is much worse if the bat gets tangled trying to free itself. A study in the Pilbara region found that barbed wire was significantly harming local bat populations. Ghost bats often fly at the height of the dominant Triodia (spinifex) plants and cannot see the wire. They are not thought to use echolocation to find wire while flying. The thorny, introduced plant lantana also poses a similar danger.

Ghost bats are very sensitive to being disturbed in their winter roosts. Even a short visit can cause them to abandon a site for several weeks or even permanently if human activity continues. While most bat species are sensitive to human disturbance, it's especially important not to disturb ghost bats at their roosts because their numbers are declining so quickly. New or reopened mining operations can also affect local colonies, even though old mines might provide daytime roosts. Old mines can also be dangerous if ceilings collapse.

The conservation status of Macroderma gigas is listed by state and federal authorities, as well as non-governmental organizations. Queensland and South Australia list the species as endangered, and Western Australia classifies it as vulnerable. Federally, it's listed as vulnerable under the EPBC Act 1999. Even though their decline is well documented, more genetic analysis is needed to officially change their status to endangered. The IUCN and The action plan for Australian mammals (2012) also list this species as vulnerable to extinction. The IUCN Red List (2019) estimates there are only between 4,000 and 6,000 adult ghost bats left. The Queensland population is less than 1,000, and the large colony at Mount Etna has declined. The Kohinoor maternity colony in the Top End is stable but at risk from mine collapse. The western populations are larger, with 3,000 to 4,000 in the Kimberley and less than 600 in the Pilbara.

Gallery