Marija Gimbutas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marija Gimbutas

|

|

|---|---|

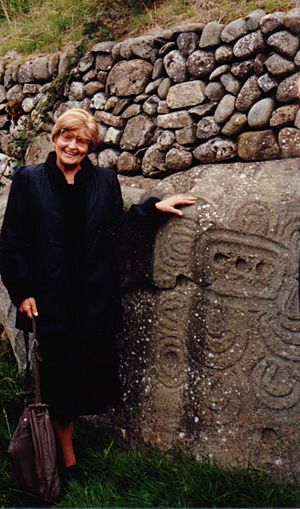

Gimbutas at the Frauenmuseum Wiesbaden, Germany 1993

|

|

| Born |

Marija Birutė Alseikaitė

January 23, 1921 Vilnius, Central Lithuania

|

| Died | February 2, 1994 (aged 73) Los Angeles, California, U.S.

|

| Nationality | Lithuanian |

| Other names | Lithuanian: Marija Gimbutienė |

| Alma mater | Vilnius University |

| Occupation | Archaeologist |

| Years active | 1949–1991 |

| Employer | University of California, Los Angeles |

| Known for | Kurgan hypothesis |

|

Notable work

|

The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe (1974); The Language of the Goddess (1989); The Civilization of the Goddess (1991); The Balts (1961); The Slavs (1971); |

| Parents |

|

Marija Gimbutas (born Marija Birutė Alseikaitė; January 23, 1921 – February 2, 1994) was a famous Lithuanian archaeologist and anthropologist. She is best known for her studies of ancient cultures from the Neolithic and Bronze Age periods in Europe. She also created the Kurgan hypothesis, which suggests where the first Proto-Indo-European people came from.

Contents

About Marija Gimbutas

Her Early Life

Marija Gimbutas was born in Vilnius, the capital of Central Lithuania. Her parents, Veronika Janulaitytė-Alseikienė and Danielius Alseika, were educated people in Lithuania.

Her mother was an eye doctor, and her father was a medical doctor. They helped start the first Lithuanian hospital in the capital city. Her father also published a newspaper and a cultural magazine. He strongly supported Lithuania's independence.

Marija's parents loved traditional Lithuanian folk art. They often invited artists, writers, and musicians to their home.

In 1931, Marija moved to Kaunas with her parents. After her parents separated, she lived with her mother and brother. When her father died suddenly five years later, Marija promised to become a scholar. She said, "All of a sudden I had to think what I shall be, what I shall do with my life... I changed completely and began to read."

Moving Abroad

In 1941, Marija married an architect named Jurgis Gimbutas. During World War II, she lived under Soviet and then German control.

Her first daughter, Danutė, was born in 1942. In 1944, Marija's family had to leave Lithuania because of the advancing Soviet army. They moved to safer areas in Europe, like Vienna and Bavaria. Marija later said that even though life was difficult, she always kept working on her studies.

Her second daughter, Živilė, was born in 1945. In the 1950s, the Gimbutas family moved to the United States. Marija had a very successful career there. Her third daughter, Rasa Julija, was born in 1954.

Marija Gimbutas passed away in Los Angeles in 1994, when she was 73 years old. She was buried in Petrašiūnai Cemetery in Kaunas, Lithuania.

Her Career and Discoveries

Education and Academic Work

From 1936, Marija Gimbutas went on trips to record traditional Lithuanian folklore. She also studied Lithuanian beliefs about death and rituals. She finished high school with honors in 1938.

She then studied linguistics at Vytautas Magnus University. Later, she went to the University of Vilnius to study archaeology, linguistics, and folklore.

In 1942, she earned her master's degree with a thesis on "Modes of Burial in Lithuania in the Iron Age."

In 1946, Marija received her doctorate in archaeology from the University of Tübingen in Germany. Her dissertation was about "Prehistoric Burial Rites in Lithuania." She often said that she had her dissertation under one arm and her child under the other when they fled Lithuania in 1944.

After moving to the United States in the 1950s, Gimbutas worked at Harvard University. She translated archaeological texts from Eastern Europe. She also became a lecturer and a Fellow at Harvard's Peabody Museum.

Later, she taught at UCLA. She became a Professor of European Archaeology and Indo-European Studies in 1964. In 1993, she received an honorary doctorate from Vytautas Magnus University in Lithuania.

The Kurgan Hypothesis

In 1956, Marija Gimbutas introduced her famous Kurgan hypothesis. This idea combined the study of special burial mounds called Kurgans with linguistics. She used this to understand where the people who spoke Proto-Indo-European languages came from and how they moved into Europe. She called these people the "Kurgans."

Her hypothesis and her way of combining different fields of study had a big impact on Indo-European studies.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, Gimbutas became a top expert on Bronze Age Europe. She also studied Lithuanian folk art and the early history of the Balts and Slavs. Her important book, Bronze Age Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe (1965), summarized much of her work. In her research, she looked at European prehistory in new ways, using her knowledge of languages, cultures, and religions. She challenged many old ideas about how European civilization began.

From 1963 to 1989, as a professor at UCLA, Gimbutas led major excavations (digs) at ancient sites in southeastern Europe. These included places like Anzabegovo in Macedonia, and Sitagroi and Achilleion in Greece. She dug deeper than other archaeologists expected and found many artifacts from daily life and religion. She studied and documented these finds throughout her career.

In 2015, three genetic studies supported Gimbutas's Kurgan hypothesis. These studies suggested that certain Y-chromosome groups, common in Europe today, spread from the Russian steppes along with Indo-European languages. They also found a genetic component in modern Europeans that was not present in earlier Neolithic Europeans. This suggests it was brought by the Kurgan people.

Later Archaeological Work

Marija Gimbutas became very well known in the English-speaking world for her last three books: The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe (1974), The Language of the Goddess (1989), and The Civilization of the Goddess (1991).

In these books, she shared her ideas about the ancient cultures of Europe during the Neolithic period. She wrote about their homes, social structures, art, and religions.

Her "Goddess" books explained what Gimbutas saw as the differences between "Old European" societies and the later Bronze Age Indo-European cultures. She believed Old European societies were peaceful, honored women, and had economic equality. She called them "goddess-centered" or "woman-centered."

On the other hand, she believed the male-dominated Kurgan people invaded Europe. They brought a new way of life where male warriors held power.

Her Influence

Marija Gimbutas's work, along with that of mythologist Joseph Campbell, is kept at the OPUS Archives and Research Center in California. This collection includes her many books and research files on archaeology, mythology, folklore, and art. It also has over 12,000 images she took of ancient sacred figures.

Author Mary Mackey has written four historical novels that were inspired by Gimbutas's research.

See also

In Spanish: Marija Gimbutas para niños

In Spanish: Marija Gimbutas para niños

- Lewis H. Morgan

- J. P. Mallory

- Yamna culture

- Vinča script

- Johann Jakob Bachofen

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |