Mary Young Pickersgill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary Pickersgill

|

|

|---|---|

Mary Pickersgill

|

|

| Born |

Mary Young

February 12, 1776 |

| Died | October 4, 1857 (aged 81) |

| Resting place | Loudon Park Cemetery, Baltimore, section AA |

| Occupation | Seamstress, flagmaker |

| Known for | Sewing the Star Spangled Banner Flag |

| Spouse(s) | John Pickersgill |

| Children | Caroline |

| Parent(s) | William Young and Rebecca Flower |

Mary Pickersgill (born Mary Young; February 12, 1776 – October 4, 1857) was an amazing flag maker. She created the famous Star Spangled Banner Flag. This flag flew proudly over Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812.

Mary learned her skills from her mother, Rebecca Young, who was also a well-known flag maker. In 1813, Major George Armistead asked Mary to make a huge flag for Fort McHenry. He wanted it to be so big that the British could easily see it from far away.

The flag was put up in August 1813. A year later, during the Battle of Baltimore, Francis Scott Key saw the flag. He was on a British ship, negotiating a prisoner exchange. Seeing the flag still flying inspired him to write a poem. This poem later became "The United States National Anthem" in 1931.

Mary became a widow at age 29. She was very successful with her flag-making business. By 1820, she could buy the house she had been renting in Baltimore. She also worked to help others. She focused on finding homes and jobs for women who needed help. From 1828 to 1851, she led the Impartial Female Humane Society. This group helped poor families with school money for kids and jobs for women. Under Mary's leadership, they built a home for older women. Later, they added a home for older men next to it. These homes eventually became the Pickersgill Retirement Community in Towson, Maryland. It opened in 1959.

Mary Pickersgill passed away in 1857. She is buried in Loudon Park Cemetery in Baltimore. Her daughter put up a monument for her. Later, other groups added a bronze plaque. The house where Mary lived for 50 years is now known as the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House. It became a museum in 1927. Many people worked hard to save this historic house.

Contents

Early Life and Learning to Make Flags

Mary Young was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on February 12, 1776. She was the youngest of six children. Her mother, Rebecca Flower, became a widow when Mary was only two years old. Rebecca owned a flag shop in Philadelphia. There, she made flags for the Continental Army. Her advertisement from 1781 said she made "All kinds of colours, for the Army and Navy."

Mary's mother moved the family to Baltimore, Maryland, when Mary was a child. It was from her mother that Mary learned the special skill of making flags.

On October 2, 1795, when Mary was 19, she married John Pickersgill. He was a merchant. Mary moved back to Philadelphia with him. Mary had four children, but only one, a daughter named Caroline, lived past childhood. Mary's husband died in London in 1805. This left Mary a widow at 29. In 1807, Mary moved back to Baltimore with Caroline and her 67-year-old mother.

The family rented a house at 44 Queen Street. This house is now known as the Star Spangled Banner Flag House and 1812 Museum. Mary started a flag-making business there. She also took in boarders to help make money. Her customers included the United States Army, the United States Navy, and merchant ships.

The Famous Fort McHenry Flag

In 1813, the United States was fighting Great Britain. Baltimore was getting ready for a possible attack. The British Royal Navy controlled the Chesapeake Bay. Major George Armistead commanded the soldiers at Fort McHenry in Baltimore. He felt the fort was ready for battle, but it needed a flag. He wanted a flag "so large that the British will have no difficulty seeing it from a distance."

A group of leaders, including Major Armistead, visited Mary Pickersgill. They asked her to make two flags. One was a huge American flag, 30 by 42 feet. The other was smaller, 17 by 25 feet. Making such large flags was a huge job. Mary needed help. She worked with her daughter Caroline, her two nieces Eliza and Margaret Young, and an apprentice named Grace Wisher. Her elderly mother, Rebecca, also likely helped. Other local seamstresses were hired too.

They often worked late into the night. They even used a nearby brewery's malt house to spread out the giant flag. Mary's daughter later wrote that her mother placed the stars on the floor. She also made sure the flag was securely attached to prevent it from being torn by cannonballs. This careful work was important during the battle.

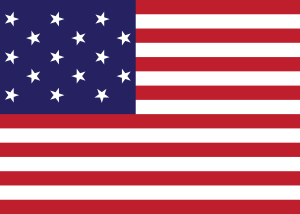

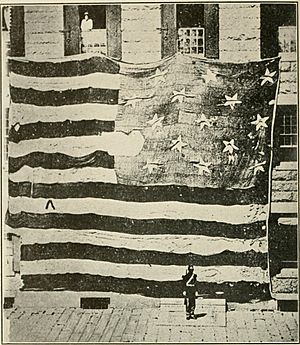

The large flag used over 400 yards of fabric. It had 15 stripes and 15 stars, one for each state at the time. The stars were made of cotton, and the stripes were made of English wool. Each stripe was 2 feet wide, and each star was 24 inches across. Mary and her team finished the flags in six weeks. She delivered them to Fort McHenry on August 19, 1813. This was a full year before the Battle of Baltimore.

The main flag weighed about 50 pounds. It took 11 men to raise it on a 90-foot flagpole. This huge flag could be seen for miles. Mary and her niece Eliza Young received $405.90 for the large flag. They got $168.54 for the smaller storm flag.

The smaller flag might have been flying when the British first attacked Fort McHenry on September 13, 1814. The weather was bad with heavy rain. However, it was Mary's large flag that was flying at daybreak on September 14. This was after the British stopped firing. A British officer wrote in his diary that the Americans raised a "splendid ensign" over the fort.

While on a British ship, Francis Scott Key saw this flag. It inspired him to write his famous poem, "The Defence of Fort McHenry." This poem later became the United States National Anthem in 1931.

After the battle, Major George Armistead kept the flag. After he died, his wife, Louisa, owned it. She allowed it to be shown sometimes. She also gave pieces of it away as gifts, which was common back then. The flag eventually went to her daughter and then her grandson. In 1907, her grandson loaned it to the Smithsonian. In 1912, the loan became permanent.

The flag has been carefully preserved over the years. Starting in 1998, it underwent an $18 million conservation project. Today, this flag, made by Mary Pickersgill and her helpers, is a very important artifact. It is the centerpiece of the National Museum of American History.

Later Life and Helping Others

By 1820, Mary Pickersgill's business was doing so well that she bought the house she was renting. She lived there for the rest of her life. Her success allowed her to focus on helping people in need. She worked on issues like housing, finding jobs, and giving money to women who were struggling. She did this many years before these issues became widely discussed.

The Impartial Female Humane Society was created to help poor families. It helped educate their children and find jobs for women. Mary Pickersgill was the president of this society from 1828 to 1851. Under her leadership, a home for older women finally opened in Baltimore in 1851. After her time as president, a home for older men was built next to the women's home in 1869.

In 1959, the two homes joined together and moved to Towson, Maryland. In 1962, the new place was named the "Pickersgill Retirement Community." This honored Mary, who was so important in making it happen.

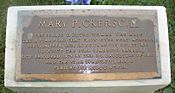

Mary Pickersgill died on October 4, 1857. She is buried in Loudon Park Cemetery in southwest Baltimore. Her daughter Caroline put up a monument for her. Later, groups like the United States Daughters of 1812 and the Star Spangled Banner Flag House Association placed a bronze plaque at her grave.

Mary Pickersgill's Legacy

Mary Pickersgill is remembered for making the flag that inspired Francis Scott Key to write the United States National Anthem. But she is also remembered for her kindness and help to society. Her many years as president of the Impartial Female Humane Society show this. This society eventually became the Pickersgill Retirement Community.

Her house, known as the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House, is also part of her legacy. It stands in downtown Baltimore and is a National Historic Landmark.

Around the time of America's 200th birthday, artist Robert McGill Mackall painted a picture. It shows Mary Pickersgill and her helpers sewing the "Star-Spangled Banner" in the malt house. A copy of this painting is at the Maryland Historical Society.

A World War II ship, the SS "Mary Pickersgill", was named after her. There is also a type of flower called the Mary Pickersgill Rose.

In 1998, I. Michael Heyman, who was the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, wrote about the flag:

I am often asked which of our more than 140 million objects is our greatest treasure, our most valued possession. Of all the questions asked of me, this is the easiest to answer: our greatest treasure is, of course, the Star-Spangled Banner.

Family Connections

Mary Pickersgill's uncle, Colonel Benjamin Flower, fought in the American Revolutionary War. General George Washington gave him a sword for his excellent work. This was for moving people out of Philadelphia safely when the British took over the city in 1776.

Mary's oldest brother, William Young, also made flags. It is likely that his two daughters, Eliza and Margaret, were the nieces who helped Mary make the Star-Spangled Banner flag. Her sister, Hannah Young, married Captain Jesse Fearson. He was a privateer ship commander during the War of 1812. He was captured by the British but later escaped.

Mary's only child who survived to adulthood was Caroline (1800-1884). Caroline married John Purdy. They did not have any children who survived. Later in her life, Caroline wrote a letter to Major Armistead's daughter. In the letter, she said she was "widowed and childless." She also shared some history about her mother and how the Star-Spangled Banner flag was made.