Moscow gold (Spain) facts for kids

The Moscow Gold (Spanish: Oro de Moscú) was a large amount of gold, about 510 tonnes. This was 72.6% of all the gold reserves of the Bank of Spain. This gold was moved from Madrid to the Soviet Union (Russia) a few months after the Spanish Civil War started.

The government of the Second Spanish Republic, led by Francisco Largo Caballero, ordered this transfer. His finance minister, Juan Negrín, was key in this decision. The term "Moscow Gold" also covers how this gold was later sold to the USSR and how the money was used. Another part of Spain's gold, about 193 tonnes, was sent to France. This is sometimes called the "Paris Gold".

Because the world knew about this gold in Moscow, the term "Moscow Gold" became popular for any Russian money used around the world. Since the 1970s, this event in Spanish history has been a big topic for books and discussions. It has caused a lot of debate, especially in Spain. People disagree about why the gold was sent, how it was used, and its effects on the war. They also debate its impact on the Spanish government in exile and relations between Spain and the Soviet Union.

Contents

Why the Gold Was Moved

The Spanish Civil War Begins

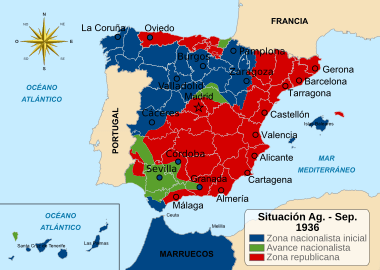

The Spanish Civil War started on July 19, 1936. This happened after a failed attempt by parts of the Spanish Army to overthrow the government. About a third of Spain ended up under the control of these rebel forces, called Nationalists. Generals like Emilio Mola and Francisco Franco led the Nationalists. They quickly sought help from Italy and Germany.

The Spanish Republic also looked for help, mainly from France. This led to other countries getting involved in the war. Both sides needed military equipment to keep fighting.

Europe's Non-Intervention Policy

At the start of the war, France had a government called the Popular Front. The French Prime Minister, Léon Blum, wanted to help the Spanish Republic. However, other parties in his government disagreed. The United Kingdom also warned against getting involved. They wanted to avoid upsetting Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

So, on July 25, 1936, France stopped sending supplies to either side in Spain. On the same day, Hitler sent planes and people to help the Nationalists. Soon after, Mussolini also sent planes and supplies. These were used to move Nationalist troops from Africa to Spain.

On August 1, France suggested a "Non-Intervention Agreement in Spain" to other countries. Britain supported this idea. The Soviet Union, Portugal, Italy, and Germany also joined the Non-Intervention Committee on September 9. However, Italy, Germany, and Portugal kept sending help to the Nationalists. The Republic also got supplies from Mexico and through illegal markets.

Nationalist Advances and Soviet Help

In August and September 1936, the Nationalist forces won important battles. They secured the border with Portugal and closed the border with France in the Basque region. These victories happened as the Soviet Union decided to get more involved. The USSR set up diplomatic relations with Spain and sent its first ambassador, Marcel Rosenberg, on August 21.

By late September, communist parties worldwide were told by Moscow to recruit fighters for the International Brigades. These groups joined the fighting in November. The Nationalists also won the Siege of the Alcázar on September 27. This allowed Franco's forces to focus on attacking Madrid.

In October 1936, the Soviet Union sent military aid to the new Spanish government. This government was led by Prime Minister Francisco Largo Caballero and included two communist ministers. The Soviet Union defended its actions by saying that Italy and Germany had already broken the Non-Intervention Agreement.

Spain's Gold Reserves

In May 1936, just before the Civil War, Spain had the fourth-largest gold reserves in the world. Most of this gold was gathered during World War I, when Spain remained neutral. The gold was mainly kept at the Bank of Spain's main building in Madrid. Some was also in other cities and a small amount in Paris. The reserves were mostly Spanish and foreign gold coins. There were very few gold bars.

The value of the gold was well known. The New York Times reported on August 7, 1936, that Spain's gold in Madrid was worth 718 million U.S. dollars. This was about 635 tonnes of pure gold.

The Bank of Spain was a private company but was controlled by the government. The government could appoint the Bank's governor and some council members. A law from 1921, called the Cambó Law, set rules for how the gold reserves could be used. The government needed approval from the Council of Ministers to sell gold. This was mainly to control the value of the Spanish currency (peseta) and help the economy.

Historians have debated if moving the gold was legal. Some say it broke the law. Others say the government followed the law, especially given the emergency of the Civil War. The government also started putting people loyal to the Republic in charge of the Bank of Spain in August 1936.

The Paris Gold

When the Civil War began, the Nationalists set up their own government. They saw the Republican government in Madrid as illegal. They also created their own central bank in Burgos. Both sides claimed to be the real Bank of Spain. The Republican government controlled the main Bank of Spain building in Madrid and its gold. The Nationalists controlled bank branches in their areas.

On July 26, the Republican government announced it would send some gold to France. The Nationalists found out and said this was illegal under the Cambó Law. They issued a decree on August 25, saying that any money deals made by the Republican government were invalid.

The French Finance Minister, Vincent Auriol, and the head of the Bank of France, Émile Labeyrie, allowed these transfers. They were against fascism and wanted to strengthen France's own gold reserves. The Non-Intervention Committee did not stop the gold from going to France. The new Spanish government, led by Prime Minister Largo Caballero, continued this policy. France and Britain ignored the Nationalist complaints.

By March 1937, about 174 tonnes of pure gold had been sent to the Bank of France. This was 27.4% of Spain's total gold. In return, the Spanish government received about 3,922 million French francs (around US$196 million). This money was used to buy military supplies and other goods. More gold, silver, and jewelry were also secretly sent to France. The Republican government said these actions were necessary because of the war.

Later, 40.2 tonnes of gold stored in France were given back to the Francoist government after the war ended. This was the only successful claim on Spain's gold reserves.

From Madrid to Moscow

Why the Gold Went to Russia

On September 13, 1936, a secret order was signed by Finance Minister Juan Negrín. This order allowed the gold reserves of the Bank of Spain to be moved. The order said the government would later explain its actions to the Spanish parliament, but this never happened.

Manuel Azaña, the President of Spain, also signed the order. However, he later said he did not know the gold's final destination. Largo Caballero said Azaña was not fully informed because of his emotional state and the need for secrecy.

Did this decision need to be known by many people? No. An indiscretion would cause an international scandal [...] It was decided that the President of the Republic should not know about it, as he was in a truly sad state of mind. So, only the Prime Minister (Largo Caballero himself), the Minister of Finance (Negrín), and the Minister of the Navy and Airforce (Indalecio Prieto) knew. But only the first two negotiated with the Russian government.

—Francisco Largo Caballero

Many historians believe the gold was moved because the Nationalist army, led by Francisco Franco, was quickly advancing towards Madrid. When the decision was made, Franco's army was only 116 kilometers from the capital. However, the Nationalists did not reach Madrid for two more months. Franco decided to help his supporters in the Siege of the Alcázar first. Madrid held out until the end of the war, and the Republican government moved to Valencia on November 6.

Prime Minister Largo Caballero said the gold had to be moved because of the Non-Intervention Pact. He also said democratic countries had stopped helping Spain. This left Madrid in danger.

Since the fascists were at the gates of Spain's capital, [Minister of Finance Negrín] asked the Council of Ministers for permission to move the gold reserves of the Bank of Spain outside the country, to a safe place, without saying where. [...] First, he moved them to the forts of Cartagena. Later, fearing a Nationalist landing, he decided to move them outside Spain. [...] There was no other place but Russia, a country that helped us with weapons and supplies. And so, they were delivered to Russia.

—Francisco Largo Caballero

However, some, like Luis Araquistáin, believed the Soviets forced Spain to send the gold.

Historians mostly agree that Finance Minister Negrín was the main person behind the transfer. But it is not clear who first suggested sending the gold outside Spain. Some say Soviet agent Arthur Stashevski suggested it to Negrín. Others say Negrín himself came up with the idea. Walter Krivitsky, a Soviet intelligence general, said that Joseph Stalin wanted to make sure there was enough gold to pay for Soviet aid to Spain.

The Bank of Spain's council was told about the government's decision on September 14. This was after the gold transfer had already started. The two stockholder representatives who were not with the Nationalists resigned. They argued that the transfer was illegal because the gold belonged to the Bank, not the government. They also said the gold was needed to back up the banknotes.

Moving the Gold to Cartagena

Less than 24 hours after the order was signed, on September 14, 1936, Spanish police and militia entered the Bank of Spain. The operation was led by Francisco Méndez Aspe, a finance official. They opened the vaults and took out all the gold. The gold was put into wooden boxes, weighing about 75 kilograms each.

The boxes were loaded onto trucks and taken to the Atocha railway station in Madrid. From there, they were transported by train to Cartagena. Cartagena was chosen because it was a major naval base, well-defended, far from the fighting, and allowed for sea transport.

The gold was heavily guarded during its journey. A few days later, the Bank's silver, worth about 656 million Spanish pesetas, was also moved. This silver was later sold to the United States and France.

With the gold safe in Cartagena, it seemed the secret order of September 13 was fulfilled. The Nationalists protested when they found out. However, on October 15, Negrín and Largo Caballero decided to send the gold from Cartagena to Russia.

On October 20, Alexander Orlov, the head of the Soviet secret police (NKVD) in Spain, received a secret telegram from Stalin. It ordered him to arrange the shipment of the gold to the USSR. Orlov worked with Negrín to prepare the transfer. He later said he used Soviet tank crews to help with the operation.

On October 22, 1936, Francisco Méndez Aspe came to Cartagena. He ordered the gold boxes to be loaded onto four ships: the Kine, Kursk, Neva, and Volgoles. The gold took three nights to load. On October 25, the four ships sailed for Odessa, a Soviet port on the Black Sea. Four Spaniards, who held the keys to the Bank of Spain's vaults, went with the gold.

Out of 10,000 boxes of gold, about 7,800 to 7,900 boxes were taken to Odessa. This was about 510 tonnes of gold. The exact number of boxes is debated, but the final receipt showed 7,800.

How the Gold Was Used

Negrín signed 19 orders between February 1937 and April 1938 to sell the gold. The gold was converted into British pounds, U.S. dollars, or French francs. Most of the gold, about 415 tonnes, was sold in 1937. Another 58 tonnes were sold in early 1938. Some gold was also used to guarantee a loan. By August 1938, only about 2 tonnes remained.

Spain received about 469.8 million U.S. dollars from selling the gold. About 131.6 million dollars stayed in the USSR to pay for various purchases and costs. The Soviets kept about 3.3% of the money for commissions, transport, and other expenses. The remaining 72% (338.5 million U.S. dollars) was sent to a Soviet bank in Paris called Eurobank. From Paris, Spanish officials used this money to buy military supplies in places like Brussels, Prague, Warsaw, New York, and Mexico.

When the Spanish gold arrived in Moscow, the Soviets immediately demanded payment for the war supplies they had sent. These supplies had seemed like a gift at first. The Soviet agent Stashevski asked Negrín for 51 million U.S. dollars for debts and the cost of moving the gold. On the Nationalist side, Germany and Italy allowed Franco to pay his debts after the war. Some historians have criticized the Soviets' actions.

Historians who have seen the "Negrín dossier" (documents about the gold) believe the Soviets did not cheat Spain. However, Spain had to pay for everything. Nothing was free from their "Russian friends." Some historians, like Gerald Howson, believe the Soviets did cheat Spain. They claim Stalin made the prices of supplies higher by changing exchange rates.

Some scholars also mention that the communists gained more power because the Soviet Union controlled the gold. José Giral said that even if payments for weapons were made, the Soviet Union would not send supplies unless the Spanish government appointed important communists to police and military roles.

Historian Ángel Viñas believes the gold was completely used up less than a year before the war ended. He says it was all spent on military supplies and related costs. However, other historians like Martín Aceña and Olaya Morales disagree. They say there isn't enough proof to confirm Viñas's conclusion. If the gold was all sold, the fate of all the money sent to the Paris bank is still unclear. No Soviet or Spanish documents fully explain these operations. Martín Aceña says the investigation into the gold is not finished. Once the gold was gone, the Spanish Republic lost its ability to get loans.

Money Problems in Spain

Moving the Bank of Spain's gold to Moscow is seen as a major cause of Spain's money problems in 1937. While the gold provided funds, its removal hurt the country's currency. The Nationalists tried to expose the gold transfer. This made people lose trust in the government's finances. A government order on October 3, 1936, forcing Spaniards to give up all their gold, caused widespread alarm. Even though the government first denied sending gold abroad, it later admitted to making payments with it.

Without gold to back up its banknotes, and with the currency already losing value, the Republican government printed more and more banknotes. These new notes had no gold or silver backing. By April 1938, the amount of new banknotes in Republican areas had increased by 265.8% compared to July 1936. This caused huge inflation. Prices in Republican areas went up by as much as 1500%. People started hoarding precious metals. Metal coins disappeared and were replaced by paper or cardboard money.

People did not want Republican banknotes because they were losing value. Also, if Franco won the war, these new banknotes would become worthless. The government could not fix the lack of metal coins. So, local towns and institutions started printing their own temporary money. Some of these were not accepted in nearby towns.

The Nationalists claimed that this inflation was planned and created on purpose.

The Republican government blamed the free market for the economic problems. They suggested that the government should control all prices and the economy. The Communist Party of Spain openly stated its position in March 1937:

...all our efforts must be focused, with full strictness, against the real enemies, against the big factory owners, against the big business owners, against the pirates of the banking industry, who, of course, within our territory have mostly been removed, but some still remain who must be quickly removed, because these are the true enemies and not the small factory owners and business owners.

—José Díaz Ramos

Internationally, people started to see the Republic as having a revolutionary, anti-capitalist movement. This view was supported by Spanish business leaders, like former Minister Francesc Cambó, who was a Nationalist supporter. Naturally, with their businesses and property at risk, Spanish and international financial groups supported the Nationalists. This sped up the fall in value of the Republican peseta.

After the War

Republican Divisions in Exile

In the last months of the Civil War, Republicans became deeply divided. Some wanted to continue the war and link it to the coming Second World War. Others wanted to end the conflict by negotiating with the Nationalists. Negrín, the Prime Minister, wanted to continue fighting. Only the Spanish Communist Party (PCE) supported him. Almost all other parties, including his own Socialist party (PSOE), were against him.

Indalecio Prieto had left Negrín's side in August 1937. He accused Negrín of giving in to communist pressure to remove him from the government. By late 1938, the conflict between communists and socialists led to violent clashes.

This division led to a military coup by Colonel Segismundo Casado in March 1939. The PSOE actively supported this coup. The new government removed communists and Negrín's supporters. Negrín fled Spain, and the coup sped up the end of the Civil War. Casado tried to negotiate peace with Franco, but Franco only accepted an unconditional surrender. Negrín was accused of being a communist puppet and ruining the Republic. The "Moscow gold" issue was one of the main arguments used against him.

After the war, the PSOE slowly rebuilt itself in exile. The party was led by Indalecio Prieto from Mexico. Negrín's supporters were excluded. The exiled PSOE leaders were strongly against communists and Negrín.

Some exiled Republicans, especially those who left the Communist Party, claimed that the gold, or part of it, had not been used to buy weapons. They criticized Negrín for keeping all the documents secret and refusing to explain to the government in exile. Francisco Largo Caballero, one of the main people involved, was very critical. Ángel Viñas says these criticisms created "one of the myths that have made Negrín look bad."

In January 1955, during the time of McCarthyism in the US, Time magazine reported on accusations by Indalecio Prieto and other exiled Republicans. They accused Juan Negrín of being involved with the Soviets in the "long-buried story of the gold hoard." The Francoist government used this to restart its diplomatic conflict with the Soviet Union. They accused the USSR of selling the Spanish gold in Europe. However, Time questioned if these accusations could be proven. The Francoist government had known since 1938 that the gold reserves were used up. But they still demanded the gold back.

The Negrín Dossier

The accounting records of the gold operation, known as the "Negrín dossier," have helped researchers understand what happened. After the Spanish gold arrived in Moscow, the Soviets melted the coins and turned them into gold bars. In return, they put money into the Spanish Republic's bank accounts abroad.

Juan Negrín died in Paris in late 1956. His son, Rómulo Negrín, followed his father's wishes and gave the "Negrín dossier" to a Spanish lawyer. This was to help the Spanish State try to get the gold back. Negrín wanted the documents to remain secret. However, the news soon became public, causing heated debates. In January 1957, Franco sent a diplomatic group to Moscow. Officially, they were to discuss getting Spaniards back. But it was thought they were there to negotiate for the gold, now that the Negrín dossier was found.

The same documents that Negrín had refused to give to the exiled Republican government for over 15 years were given to Franco's government. The President of the exiled Republican government, Félix Gordón Ordás, wrote on January 8, 1957:

The delivery of the documents by Negrín's son to the Francoist government is a very serious act. It shows a lack of respect for the Republican government in exile. It also shows a lack of loyalty to the Republic. This act will be judged by history.

—Félix Gordón Ordás

In April 1957, Time reported that the Soviet government, through Radio Moscow and Pravda, told Franco's government that the gold reserves in Moscow had been fully used by the Republican government to "make payments abroad." So, they were "soon all gone." The Mundo Obrero newspaper published an article on May 15, 1957:

The gold reserves of the Bank of Spain, which were sent to the Soviet Union by the Republican government during the Civil War, were completely used to pay for military supplies and other necessary goods for the Republic. The Soviet Union did not keep any of this gold. All of it was spent by the Spanish Republican government.

—Mundo Obrero

This statement had no proof and went against what important Republican government members had said. For example, Negrín had told José Giral in 1938 that two-thirds of the gold in Moscow was still available. Also, since these were not official statements, the Soviet government could deny them later. Indalecio Prieto called Pravda's statements false. He listed expenses of Spanish funds that benefited the French Communist Party.

History and Myths

Historians like Pablo Martín Aceña, Francisco Olaya Morales, and Ángel Viñas have researched this topic. Viñas was the first to access the Bank of Spain's documents. Internationally, Gerald Howson and Daniel Kowalsky have seen Soviet archives opened in the 1990s. They focused on the relationship between the Soviet Union and the Spanish Republic, and military aid.

While the decision to use the gold reserves is not much debated, its final destination is still controversial. Historians like Viñas, Ricardo Miralles, and Enrique Moradiellos defend Negrín. They believe sending the gold to the USSR made sense politically, economically, and practically. They say it was the only choice given the Nationalist advance and the lack of help from Western democracies. For them, without selling the gold, Spain could not have resisted militarily.

On the other hand, Martín Aceña believes sending the gold was a mistake. He says it cost the Republic its financial power. He argues that the USSR was far away, had a confusing financial system, and did not follow international rules. It would have been better to send the gold to capitalist countries like France or the United States. Olaya Morales, an anarchist historian, called Negrín's actions criminal. He denies Viñas's arguments and believes the "gold issue" was a huge fraud. He sees it as a major reason for the Republican defeat.

Some authors, like Fernando García de Cortázar, Pío Moa, and Alberto Reig Tapia, say the "Moscow Gold" story is a myth. They believe it was used to explain Spain's terrible situation after the war.

Images for kids

-

Royal Customs House in Madrid, where the Ministry of Finance was located.

-

Front of a 1 peseta banknote, issued in the summer of 1937 by the Municipal Council of Reus.

See also

In Spanish: Oro de Moscú para niños

In Spanish: Oro de Moscú para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |