Noe Zhordania facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Noe Zhordania

|

|

|---|---|

|

ნოე ჟორდანია

|

|

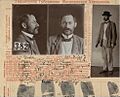

Zhordania in 1920

|

|

| Head of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia in Exile | |

| In office 18 March 1921 – 11 January 1953 |

|

| Preceded by | Himself as Prime Minister of Georgia |

| Succeeded by | Government in Exile dissolved |

| 2nd Prime Minister of Georgia | |

| In office 24 June 1918 – 18 March 1921 |

|

| Preceded by | Noe Ramishvili |

| Succeeded by | Budu Mdivani (As Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 15, 1868 Lanchkhuti, Guria, Kutais Governorate, Russian Empire (present-day Georgia) |

| Died | January 11, 1953 (aged 84) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Leuville Cemetery, near Paris |

| Political party | Social Democratic (Menshevik) Party of Georgia |

| Spouse | Ina Koreneva |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | Tbilisi Spiritual Seminary Warsaw Veterinarian Institute |

| Profession | Politician |

| Signature |  |

Noe Zhordania (Georgian: ნოე ჟორდანია; born January 15, 1868 – January 11, 1953) was a Georgian journalist and politician. He was a key leader in the socialist movement in the Russian Empire. Later, he led the government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia from 1918 to 1921. When the Bolshevik Russian army invaded Georgia, he was forced to leave for France. There, Zhordania continued to lead the Georgian government in exile until he passed away in 1953.

Contents

Noe Zhordania's Life Story

Early Years and Education

Noe Zhordania was born on January 15, 1868. His family were small landowners in the village of Lanchkhuti, in western Georgia. At that time, Georgia was part of the Russian Empire.

He went to a public school in Lanchkhuti. Then, he studied at the Ozurgeti Orthodox Theological Academy. After that, he moved to Tbilisi and graduated from the Georgian Orthodox Theological Seminary. His parents hoped he would become a priest. However, from a young age, Noe started to doubt religious beliefs.

He wrote about his thoughts:

'God is Nature herself; as for a white-bearded deity, seated upon a throne, such a personage simply does not exist'. 'I thought to myself: If Nature's lord and master is Nature itself, then who is the rightful lord and master of mankind? The general opinion was that the Tsar (King) was the lord over the people, and that the Tsar(King) was himself appointed by God. But if God did not exist any more, the Tsar(King) could not be his representative. I was therefore at a loss to understand by whose command and authority he sat upon his throne.'

While at the academy, he led a secret student group. This group opposed the problems they saw in the academy. He also read forbidden books about revolution and democracy. In 1891, he moved to Warsaw, Poland, to study at the Warsaw Veterinarian Institute. During this time, young Zhordania learned about Marxism, a political and economic theory. He started to believe that Russia was moving from socialism to Marxism. In 1892, he had to return to Georgia because he got sick.

Starting His Political Career

When Zhordania returned to Georgia, he shared Marxist ideas with workers in Tbilisi. In the 1890s, he became a leader of the first legal Marxist group in Georgia, called the Mesame Dasi (the Third Group). This group believed the working class was important for changing society. They also included the idea of national identity in their plans.

In May 1893, Zhordania traveled to Europe to avoid being arrested. In Geneva, he met other Marxist leaders. He read more Marxist books and studied the lives of workers and farmers in Switzerland. He wrote about his observations for a Georgian journal called Kvali.

In 1895, he went to Paris and studied at the French National Library. He met French socialists there. He then traveled to Germany, where Marxism began. He met Karl Kautsky, an important Marxist thinker. While in Germany, Zhordania wrote articles for Kvali about topics like Friedrich Engels and political parties in Germany.

In March 1897, Zhordania moved to London, England. He studied literature from around the world at the British Museum. In 1897, he returned to Georgia. He helped buy the journal Kvali, which became one of the first legal Marxist publications in the Russian Empire in January 1898. This was a big step for socialists.

Zhordania also wrote a "proclamation" in 1899. It asked Georgian workers to join European workers in celebrating May Day. This led to more tension between different political groups.

In 1901, clashes happened between workers and the army. Zhordania became a target for the police. He tried to escape to Europe but was arrested in Kutaisi. He spent eight months in prison, first in Tbilisi and then in Metekhi. He was accused of being involved in illegal activities, even though Kvali was a legal newspaper.

In June 1902, Zhordania was released from prison. He moved to Lanchkhuti. At this time, a peasant movement was active in the Guria region, led by Social Democrats. Zhordania was arrested again during mass arrests and sent to prison. He was later exiled to Ganja, under police watch. However, he secretly continued to be involved in party meetings.

The police decided to exile him to the Vitki Province for three years. But Zhordania escaped to Batumi and then fled to England by ferry. After traveling for three weeks, he arrived in London, then went to Paris, and finally to Geneva to meet Georgi Plekhanov.

He was invited to a meeting of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in Brussels. In 1903, he was chosen as a delegate to the 2nd Congress of the RSDLP. He joined the Menshevik group, which was one of the two main factions of the party. He became very influential.

In 1905, he edited a Georgian Menshevik newspaper in Tbilisi called Sotsial-Demokratia. This newspaper strongly criticized the Bolsheviks, the other main faction. During the Russian Revolution of 1905, he did not support armed uprisings. Instead, he wanted to create a legal workers' party.

In 1906, he was elected to the First State Duma (a kind of parliament) from the Tiflis Governorate. He became a spokesperson for the Social-Democratic group. He was also elected to the Central Committee of the RSDLP, where he stayed until 1912.

In 1907, he was sentenced to three months in prison for signing a protest against the Duma's dissolution. In 1912, he edited another Menshevik newspaper in Baku. In 1914, he worked with Leon Trotsky on a magazine where he wrote articles about national identity.

World War I and the Revolution

During World War I, Zhordania believed that Georgia should stay loyal to Russia. He thought that protesting against Russia would lead to harsh punishment. He also secretly met with Mikheil Tsereteli, who wanted Georgia to be free with help from Germany and the Ottoman Empire. Zhordania supported the idea of independence but believed they should wait for the right moment.

After the February Revolution in 1917, Zhordania led the Tbilisi council. He was elected to the executive committee of the Tbilisi Soviet. He urged workers not to follow Bolshevik ideas but to fight for a parliamentary republic. In October 1917, he returned to Georgia, feeling disappointed with the Russian Pre-Parliament.

On November 26, 1917, he became the head of the National Council of Georgia. He played a key role in making the Mensheviks powerful in Georgia.

Georgia's Independence

In May 1918, Zhordania led a meeting that declared the independent Democratic Republic of Georgia. On July 24, 1918, he became the Head of the Government of Georgia.

The Independence Act, which he helped create, included important social ideas like an eight-hour workday. However, Zhordania removed these social parts and kept only the national political ones. The National Council approved it.

In 1919, Georgia held elections for its Constituent Assembly. Out of 130 members, 109 were Social-Democrats. Zhordania was elected as the chairman of the Government on March 21, 1919.

Under Zhordania's leadership, the new government created the Tbilisi State Conservatory and the Institute of Caucasian Archaeology and History. They made Georgian the official language and founded Tbilisi State University as a Georgian language institution.

Georgia faced many challenges in 1919–20, including economic hardship and a lack of food. Zhordania tried to get other countries to recognize Georgia. In 1920, a treaty was signed with Russia, establishing diplomatic relations and giving Georgia international recognition.

In December 1920, the League of Nations did not accept Georgia as a member. But in January 1921, Georgia gained international legal recognition. In February, the Constituent Assembly adopted Georgia's Constitution.

His government successfully reformed land ownership and passed laws for social and political rights. Georgia became the only Transcaucasian nation recognized by Soviet Russia and Western powers. His government gained strong support from farmers, intellectuals, and nobles. They helped transform Georgia into a modern political nation.

However, in February–March 1921, Soviet armies invaded Georgia. This forced Zhordania and many of his colleagues to flee to France. He led the government-in-exile there. He continued to work for international recognition of Georgia's occupation and support for its independence until his death in Paris in 1953.

In 1923, Noe Zhordania appealed to Washington, saying:

In the twentieth century, before the eyes of the civilized world, I appeal to the conscience of civilized nations and all honest people to condemn this persecution of a small nation and the criminals inspiring and carrying out these barbarous acts — the Bolshevik

He also stated that Chekists (Soviet secret police) had killed many people without trial, including women, children, and intellectuals.

Life in Exile

In Istanbul, Zhordania met with French ambassadors and was invited to set up the Georgian government in exile in France. However, he was not warmly welcomed in France in April 1921. He visited Brussels and London to ask for support, but these governments were not interested.

Zhordania decided to work with European countries and help his comrades still in Georgia. He wrote:

"The European society is exhausted, they don't empathize with other's pain, they don't even recognize it, and they only care about one thing - To be by themselves, peacefully, with no worries..."

Zhordania lived first in Paris and then in Leuville-sur-Orge. He helped prepare for the Georgian revolt in 1924. Soon after, his mother and daughter, who had stayed in Georgia, were arrested.

Zhordania wrote books criticizing the Soviet Union. In 1930, he published the Georgian epic poem, "The Knight in the Panther's Skin". By 1933, he had published 12 other books, including "Combating Problems" and "True and False Communism." In Paris, he started the Georgian Social-Democratic journal "Battle" and the newspaper "Battle Cry."

Noe Zhordania passed away at 85 on January 11, 1953, in Leuville-sur-Orge, where he is buried. His memories, titled "My Past," were published after his death in 1968.

Noe Zhordania's Beliefs

Zhordania was a Marxist who leaned towards social-democracy. He focused on the role of farmers and national identity.

As a child, he grew up as an Orthodox Christian. He first questioned God's existence in school after reading "The Door to Nature." He learned that natural disasters had scientific explanations. Because of his doubts about God, he also questioned the king's power, which was believed to come from God. He strongly believed:

"The king is as fictional an authority as God. This fact made both atheism and republicanism two faces of the same coin."("My past", p. 12)

In Warsaw, Zhordania learned about Marxism. He believed that European socialism was leading workers to factories, so political actions should be based on that. He also thought that less developed countries needed political revolution, democracy, and economic growth before moving to socialism.

He had different ideas about war tactics compared to Russian Marxists. He believed it was fair to use terror in some situations. Zhordania also had traditional views on families, thinking that a person's main goal was to have a family and children.

Views on Farmers

To understand Marxism better, he traveled to Switzerland, France, Germany, and England. He found that European society was very different from Georgian society.

He was most interested in issues related to farming. In Europe, farmers owned their land and paid taxes. In Georgia, it was different. Because of this, farmers and landowners were often against each other. For Zhordania, the "agrarian question" (issues about land and farming) was very important. Unlike European and Russian Social Democratic movements, which focused on industrial workers, Zhordania believed that farmers were the main force for revolution.

"The social structure in Europe was too far away from that of Georgia. It posed the risk of influencing and changing Georgian revolutionary ideology " ("My past", p. 28)

Views on National Identity

Western European countries already had a strong national identity. So, Zhordania couldn't find much useful from their programs. It was in Poland that he learned about nationalist movements. He believed that Marxism did not deny the importance of national identity and the fight for freedom.

"If a person wants to be free, why the nation, as a large ethnic community, has not to be driven by itself, does not have its own state?"

He did not believe that promoting national identity should come first. He thought Georgia was a young nation whose national awareness only grew at the end of the 19th century. He felt that Russia had brought a more advanced economic system (capitalism) to Georgia. He also worried that if he focused too much on national issues, he would lose support from farmers, which would hurt the revolutionary movement. He only supported the cultural freedom of nations.

During World War I, he was especially against focusing on national issues. He saw it as a danger to the nation. He believed Georgia should show loyalty to Russia. However, after the October Revolution, Zhordania's views on national identity changed.

Family Life

In 1904, Noe Zhordania married Ina Koreneva (1877–1967), who was also involved in politics. They had four children: Asmat, Nina, Redjeb, and Andreika. Asmat's daughter, Ethéry Pagava, became a famous ballerina in France. Nina married Archil Tsitsishvili and had three daughters. Andreika passed away in Georgia. Redjeb Zhordania lives in New York and has one son and two daughters.

Noe Zhordania's relative, Nina Gegechkori, was married to Lavrenti Beria, a powerful Soviet secret police chief.

Works

- Noi Nikolaevich Zhordania, My Life, The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, Stanford, California, 1968, ISBN: 0-8179-4031-6

Images for kids

-

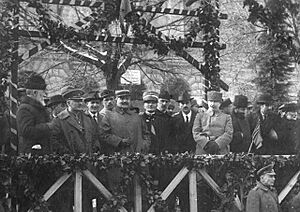

Karl Kautsky with the Georgian Social-Democrats, Tbilisi, 1920. In the first row: S. Devdariani, Noe Ramishvili, Noe Zhordania, Karl Kautsky and his wife Luise, Silibistro Jibladze, Razhden Arsenidze; in the second row: Kautsky's secretary Olberg, Victor Tevzaia, K. Gvarjaladze, Konstantine Sabakhtarashvili, S. Tevzadze, Avtandil Urushadze, R. Tsintsabadze

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |