Obscurantism facts for kids

Obscurantism (pronounced ob-SKYOOR-an-tiz-um) is when someone purposely makes information hard to understand or hides it. It's like trying to confuse people on purpose. This can happen in two main ways:

- Hiding knowledge: This means stopping people from learning or sharing information. It's like keeping secrets from the public.

- Making things confusing: This means using really complicated words or writing in a way that's hard to follow, even if the person knows the subject well.

In the 1700s, thinkers during the Age of Enlightenment used the word obscurantist for anyone who was against sharing knowledge and ideas widely. Later, in the 1800s, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche said that obscurantism isn't just about confusing one person. He believed it tries to "darken our picture of the world" and make our idea of life unclear.

Contents

Hiding knowledge

When knowledge and education are kept only for a small, powerful group, it's a form of obscurantism. This is against democracy because it means some people think others aren't smart enough to know the truth about their government or how their society works.

In 18th-century France, the political thinker Marquis de Condorcet noticed that the rich ruling class (the aristocracy) often hid information and didn't care about the problems that led to the French Revolution (1789–1799). This revolution eventually removed the king and the aristocracy from power.

In the 1800s, the mathematician William Kingdon Clifford fought against obscurantism in England. He saw religious leaders who privately agreed with evolution but publicly spoke against it, calling it un-Christian. In religion, obscurantism can be like censorship. It's when a powerful group uses people's religious beliefs to control them by hiding or changing information.

Leo Strauss's ideas

In the 20th century, the American political philosopher Leo Strauss and his followers believed that a few "enlightened" (very smart) people should govern. He thought that since ancient times, thinkers like Plato wondered if it was possible for good leaders to be completely truthful and still keep society stable. This led to the idea of the "noble lie"—a myth or untruth that leaders might tell to keep society together and get people to agree with them.

For example, Plato suggested that people might need to believe their country's land truly belongs to them, even if it was taken from others. Seymour Hersh noted that Strauss supported this idea of leaders using myths to maintain a strong society.

Some critics, like Shadia Drury, disagreed with Strauss's view. She argued that while Plato's noble lie was meant for a moral good, Strauss seemed to think that the leaders' superiority was only intellectual, not moral.

Hidden meanings in texts

Leo Strauss also suggested that some old texts have "esoteric" (hidden) meanings that are hard for most people to understand. In his book Persecution and the Art of Writing (1952), he said that some philosophers wrote in a hidden way to avoid being punished by political or religious leaders. He believed this style of writing also made readers think more deeply on their own.

Strauss thought that philosophers' writings had clear "exoteric" (obvious) teachings and hidden "esoteric" (true) teachings. He pointed out that writers sometimes left mistakes or contradictions on purpose to make readers reread the text carefully. Because he talked about this "exoteric—esoteric" idea, Strauss himself was sometimes accused of obscurantism and of writing in a hidden way.

Bill Joy's concerns

In his article "Why the Future Doesn't Need Us" (2000), computer scientist Bill Joy worried that new technologies like robotics, genetic engineering, and nanotechnology could threaten humanity. He suggested that we need to think more carefully about our inventions and their consequences.

Joy proposed limiting public access to certain powerful knowledge to protect society. Critics quickly called this idea a form of obscurantism because it was an elitist suggestion to control information. Other computer scientists, John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid, responded that Joy's idea was too narrow and didn't consider how non-scientists also influence societal problems.

Appealing to emotions

The economist Friedrich von Hayek used the term obscurantism in a different way. In his essay "Why I Am Not a Conservative" (1960), he said that political conservatism sometimes denies scientific facts because people don't like the moral consequences that might come from accepting those facts. It's like refusing to believe something true because it makes you uncomfortable.

Making things confusing on purpose

The second meaning of obscurantism is making knowledge difficult to understand. In the 1800s and 1900s, this term was used to accuse writers of purposely writing in a confusing way to hide that they didn't have many good ideas.

Sometimes, philosophers who deal with very abstract ideas are called obscurantists because their writing is hard to follow. However, writing that is unclear doesn't always mean the writer doesn't understand the topic. Sometimes, confusing writing is done on purpose for philosophical reasons.

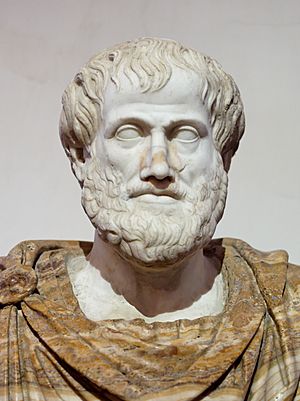

Aristotle's writings

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle divided his own works into "exoteric" (for the public) and "esoteric" (more technical, for his students). Some scholars believe his esoteric works were his unpolished lecture notes. However, a 5th-century philosopher named Ammonius Hermiae wrote that Aristotle's style was purposely confusing. He thought this would make smart people think harder, while those who weren't serious would give up.

Aristotle's book Nicomachean Ethics has been accused of ethical obscurantism because its language is very technical and philosophical. Some say it was written to educate only a small, cultured ruling class.

Kant's style

Immanuel Kant used many technical terms that ordinary people didn't understand. Later, the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer argued that philosophers who came after Kant, like Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, purposely copied Kant's hard-to-understand writing style.

Hegel's philosophy

The philosophy of G. W. F. Hegel and those he influenced, like Karl Marx, have been accused of obscurantism. Philosophers like A. J. Ayer, Bertrand Russell, and Karl Popper said Hegel's ideas were unclear. Schopenhauer called Hegel's philosophy "a colossal piece of mystification" that would make future generations laugh at how confusing it was.

However, Hegel knew people found his writing unclear. He believed that philosophical thinking often needs to go beyond everyday thoughts and concepts. In his essay "Who Thinks Abstractly?", he said that it's actually ordinary people who think "abstractly" because they use ideas without thinking about their full meaning. He argued that philosophers think "concretely" by looking at the bigger picture of concepts, which can make their ideas seem obscure to others.

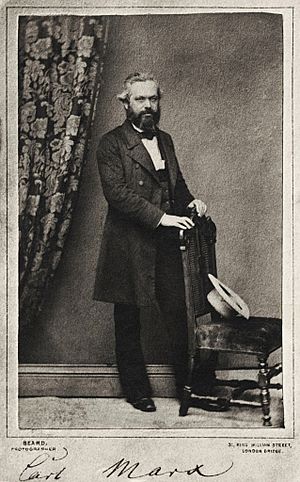

Marx's views

In his early writings, Karl Marx criticized German and French philosophy for being confusing and having politically motivated obscurantism. Later thinkers influenced by him, like György Lukács, made similar arguments. However, philosophers like Karl Popper and Friedrich Hayek also criticized Marx's own philosophy as obscurantist.

Heidegger's complexity

Martin Heidegger and those he influenced, like Jacques Derrida, have been called obscurantists by critics. Bertrand Russell wrote that Heidegger's philosophy was "extremely obscure" and that his language seemed to be "running riot." Russell suspected that Heidegger's ideas, like "nothingness is something positive," were psychological observations disguised as logic. This shows how many 20th-century analytic philosophers felt about Heidegger's work.

Derrida's writing

Newspapers like The New York Times and The Economist described Jacques Derrida as a philosopher who was purposely obscure.

Richard Rorty suggested that Derrida used words that couldn't be defined, or used defined words in so many different ways that they became meaningless. This made it hard for readers to understand his work, which, Rorty argued, allowed Derrida to avoid being tied to any specific philosophical ideas.

Derrida's work was very controversial, especially among academics in America and Britain. When the University of Cambridge gave him an honorary degree, many philosophers protested. They argued that his writings were "unintelligible" and that giving him an award for "attacks upon the values of reason, truth, and scholarship" was not a good reason.

John Searle also commented on Derrida's work, saying it had a "low level of philosophical argumentation," "deliberate obscurantism of the prose," and "wildly exaggerated claims." He felt Derrida tried to seem profound by making claims that were actually "silly or trivial."

Lacan's lectures

Jacques Lacan was a thinker who actually defended being obscure to some extent. When his students complained that his lectures were hard to understand, he famously replied, "The less you understand, the better you listen." He also said that his writings were not meant to be understood in a logical way, but rather to create a feeling or meaning in the reader, like mystical texts do. His obscurity often came from his many references to other complex philosophers.

The Sokal affair

The Sokal affair (1996) was a famous trick played by physics professor Alan Sokal. He submitted a fake article called "Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity" to Social Text, an academic journal. The article was full of nonsense, claiming that physical reality is just a "social construct." Sokal wanted to see if the journal would publish it if it sounded impressive and fit the editors' ideas, even if it was meaningless.

The journal published Sokal's fake article. Sokal later revealed his hoax in another magazine, explaining that he did it to test the "intellectual standards" of academic publishing. He concluded that Social Text didn't bother to check the facts or ask a scientist to review an article about quantum physics.

Sokal said his hoax was a protest against obscurantism in the social sciences—the use of confusing, vague, and pretentious language. He argued that such ideas are often "false (when not simply meaningless)" and that "facts and evidence do matter." He believed that much academic writing tries to hide these simple truths with complicated language.

Sokal described his fake article as a mix of "left-wing politics, fawning references, grandiose quotations, and outright nonsense." Obscurantism can be used to make people's existing beliefs seem very important, or to use confusing words to avoid discussing opposing ideas, sometimes denying that physical reality exists.

See also

In Spanish: Oscurantismo para niños

In Spanish: Oscurantismo para niños

- Anti-intellectualism

- Cover-up

- Disinformation

- Doublespeak

- Dumbing down

- Fundamentalism

- Paternalism

- Perception management

- Philosopher king

- Politicization of science

- Pseudophilosophy

- Pseudointellectual

- Psychological manipulation

- Whataboutism

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |