Old St. Andrew's Parish Church facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Old St. Andrew's Parish Church

|

|

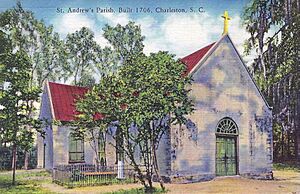

Old St. Andrew's in 2021

|

|

| Nearest city | Charleston, South Carolina |

|---|---|

| Area | 12.9 acres (5.2 ha) |

| Built | 1706 |

| Architectural style | Colonial |

| NRHP reference No. | 73001694 |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1973 |

Saint Andrew's Parish Church is a very old church located in Charleston, South Carolina. It sits along the west side of the Ashley River. Built in 1706, it is the oldest church building still standing south of Virginia. Its historic graveyard has been there since the church was first built.

In 1723, the church was made bigger into the shape of a cross. It is the only colonial church in South Carolina that still has this cross shape. People often call it Old St. Andrew's. In 1973, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places, which lists important historical sites. Old St. Andrew's is still an active church today. It is part of the Anglican Diocese of South Carolina and the Anglican Church in North America.

Contents

The Church's Early Years: 1700s

How the Church Started

In 1706, a law called the Church Act made the Church of England the official religion in the Carolina colony. This law created a system of "parishes," which were like local districts. These parishes handled both government and church duties. Ten parishes were named, and St. Andrew's Parish Church was chosen to serve people living along the Ashley River.

St. Andrew's Parish was quite large, about 280 square miles. It stretched from Folly Island and the Atlantic Ocean in the south. It went north into what is now Dorchester County. The place where English settlers first landed in 1680, now called Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site, was in St. Andrew's Parish.

Traveling across the large parish was hard for people in the northern part. So, in 1717, the parish was split in half. The northern part became St. George's, Dorchester. The new St. Andrew's Parish included today's West Ashley and James Island. It acted as a government area until 1865.

First Years of the Church

St. Andrew's Parish Church was built in 1706. It was made of brick and had a pine roof. The church was 40 feet long and 25 feet wide. It had two doors and five small, square windows. A wider "great" door was used by important people. A narrower "small" door was for common people and clergy. It is believed that enslaved Africans built the church. A seven-acre graveyard surrounded the building.

The first minister, called a rector, was Rev. Alexander Wood. He arrived in 1708 but died two years later. The next rector was Rev. Ebenezer Taylor (1712–17). His time was difficult because he had many arguments with the church leaders and people. Taylor was a Presbyterian minister who became an Anglican minister. He was supposed to attract Presbyterians to the Church of England.

However, Taylor did not succeed in bringing Presbyterians to the Anglican church. His strong personality and unfamiliarity with Anglican ways upset the Anglicans he was meant to serve. He also worked with enslaved people on local plantations, which was unusual for ministers at that time. During his time, Indian raids happened close to the Ashley River. Taylor often complained about how his church members treated him. Eventually, the church leaders locked him out of the church. In 1717, Taylor was sent away to North Carolina, where he died three years later.

Growth and Changes

Rev. William Guy became the rector in 1718 and served until 1750. His 32 years were one of the longest times a minister served the church. Unlike Taylor, William Guy was well-liked by his church members.

Reverend Guy wrote many letters about life in the parish. He started the church's first register, which recorded births, baptisms, marriages, and deaths. Churches kept these records before government agencies did. He also built a small chapel on James Island. This made it easier for people living there to attend church.

The church's land, called a glebe, was expanded during Guy's time. It grew from 26 acres to 83 acres. In 1750, a small, old wooden house for the minister was replaced with a large, two-story brick house.

As more people moved to the Ashley River area, the 1706 church became too small. Starting in 1723, the church was expanded into the shape of a cross. This made the church three times bigger. New parts included the chancel and transept at the east end. The church also got new windows and a curved ceiling. The old pine roof was replaced with cypress. Cedar pews were added for seating. The outside brick was covered with stucco to make it look like stone. Even though Anglican churches got public money, it was not enough. The expansion needed donations from church members. The finished church looked simple but elegant.

A Time of Wealth

St. Andrew's Parish Church became very successful because of a strong economy. This was mainly due to growing rice. This success was possible because of the slave labor system brought from Barbados and the West Indies. In 1705, there were about 130 white families and 150 enslaved people along the Ashley River. By 1728, Reverend Guy estimated there were 800 free white people and 1,800 enslaved black people in the parish.

Rev. Charles Martyn took over after William Guy in 1752. He also served for a long time, leaving in 1770 due to poor health. The parish continued to be wealthy. Another important crop, indigo, was grown. Eliza Lucas Pinckney perfected indigo farming at her father's plantation in St. Andrew's Parish. Growing both rice and indigo made the parish one of the richest areas in colonial British North America. More enslaved labor was needed for these crops. By 1777, the enslaved population in the parish reached 3,460.

Fire and Rebuilding

In the early 1760s, a big fire damaged the church. Anything made of wood would have burned. However, the brick walls from 1706 and 1723 remained standing. The church was fully repaired and reopened in 1764. Church members paid for the repairs through donations.

After the fire, new features were added. These included a beautiful reredos or altarpiece at the east end. A balcony was built at the west end. The church floor was replaced with stone and tile pavers. The large window behind the altar was not replaced. Instead, the wall was bricked up, and the reredos was added. This altarpiece has four tablets showing the Lord's Prayer, Ten Commandments, and Apostles' Creed. Such an expensive decoration showed how wealthy the parish was. The balcony, first installed in 1754, was rebuilt for people who could not afford to buy their own seats. The stone and tile floor was later covered in 1855. It was rediscovered and brought back in 1969.

The American Revolution's Impact

After Charles Martyn left, Rev. Thomas Panting (1770–71) and Rev. Christopher Ernst Schwab (1771–73) served as rectors. It would be 14 years until a new rector was found after the American Revolution.

The American Revolution greatly affected the church, the minister's house, and the chapel on James Island. In March 1780, British and Hessian soldiers faced colonial cannon fire near the church. British General Alexander Leslie ordered Hessian Captain Johann Ewald to cross the creek and stop the rebels. This was to prevent cannons from destroying the church. Ewald's men got stuck in the mud, allowing the colonials to escape. The British and Hessians camped in the churchyard overnight. They later marched to Charles Town and captured the city. The war left a difficult mark on St. Andrew's Parish. The church was "much Injured and pulled to pieces by the British Army." The minister's house was burned, and the chapel on James Island was destroyed.

The 1800s: Challenges and Changes

Slow Recovery and Economic Hardship

After the war, church members worked to repair their church, rebuild the minister's house, and find a new rector. In 1785, the state government gave the church leaders authority over many parish issues. A new rector, Rev. Thomas Mills, was hired in 1787. He was the last rector from England. He had fled his home country because he strongly supported American independence. His 29 years (1787-1816) brought stability to the church's leadership.

The wealth before the war was replaced by economic difficulties. Rice farming declined, and low-quality indigo could not compete in world markets. St. Andrew's, like other rural parishes, still relied heavily on enslaved African American labor. About 90 percent of the population was enslaved. An observer in the 1840s noted that the Ashley River plantations, once very productive, were now "almost left untilled." This showed a sad sense of abandonment and ruin.

St. Andrew's did not have a regular minister for 11 of the next 13 years. The church building was used as a voting place until the 1830s. Rev. Joseph Gilbert was chosen as rector in 1824 but died the same year. He was followed by Rev. Paul Trapier (1829–35) and Rev. Dr. Jasper Adams (1835–38). The chapel on James Island became its own church, St. James, in 1831. A white marble tablet was placed over the south exterior door. It honored Jonathan Fitch and Thomas Rose, who supervised the church's building in 1706.

Ministry to Enslaved People

Rev. James Stuart Hanckel served St. Andrew's from 1838 to 1851. He ministered to his small white congregation in the church during the cooler months. Church repairs were finished in 1840. A baptismal font was installed in 1842, which is still used today. The first confirmation class was held in 1843.

Soon after arriving, Hanckel began a regular ministry to enslaved people. This was the first focused effort at St. Andrew's to reach out to African Americans on plantations. The church register, started in 1830, recorded many baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and burials of enslaved people during Hanckel's time. Three chapels were built on plantations for religious teaching and worship. Middleton Chapel and Magwood's Chapel were built in 1845. To the north, John Grimké Drayton added Magnolia Chapel in 1850. By the end of Hanckel's time, there were twice as many black church members as white.

John Grimké Drayton took over from Stuart Hanckel in late 1851. Drayton was a wealthy plantation owner, a famous gardener, and a dedicated Episcopal priest. He served St. Andrew's for 40 years (1851–91), the longest time in the church's history. He saw the last years before the Civil War, the war's destruction, and the slow recovery. He continued ministering to enslaved people and expanded on what Stuart Hanckel had started. From 1851 to 1859, black church members outnumbered white members five to one.

1855 Restoration

Early in Drayton's time, the church was in very poor condition. In 1855, it was fully restored under the leadership of Col. William Izard Bull. Much of how the church looks today comes from Bull's restoration. The old high-backed pews were too damaged to save. Bull installed new, more fashionable low-backed pews, each with a door. He drew his pew plan on the plaster of the north wall. It was covered up and not found again until almost a century later. The pulpit and reading desk were moved to their current spots. Cast iron railings were added around the pulpit, desk, and altar. The old stone and tile floor was replaced with large, square sandstone pavers. The earlier flooring was buried underneath. Bull placed memorial tablets for his ancestors on the southeast wall. Paintings of scenery and cherubs on the walls were removed.

The Civil War's Impact

Reverend Drayton stayed in the parish during the Civil War. He also served another church in Flat Rock, North Carolina, during the summer. He held his last service at St. Andrew's on February 12, 1865. Confederate forces had left Charleston, leaving the area unprotected from Union troops and freed slaves who came with them.

Drayton returned from Flat Rock to find his home at Magnolia burned. However, his beautiful gardens were saved. He moved to the Grimké family home in Charleston. Union forces took over St. Andrew's Parish Church to use as a public meeting and voting place. Drayton could not get into his own church.

A report after the war described a sad scene for St. Andrew's Parish. The church survived, but it was "in the midst of a desert." Almost every home on the west bank of the Ashley River was burned. The report said it would take many years for enough people to return, rebuild their homes, and restart church services.

After the War: Ministry to Freed People

After the war, newly freed black people left their former white church connections. This was a huge change. However, in St. Andrew's Parish, freed people reunited with their white minister, Rev. John Grimké Drayton. In 1867, Drayton met a group of freedmen who asked him to restart religious services. This was a very important request.

Drayton began meeting with his black church members at the three plantation chapels. He preached to "overflowing congregations" and held services on the first, third, and fifth Sundays from November to May. There were almost no white church members. In 1875, Drayton wrote that his people's interest had not lessened. They continued to gather for worship despite long distances. By 1880, there were only 617 black Episcopalians in the state. The St. Andrew's chapels were one of only three congregations with many black members. Black church members in St. Andrew's Parish now outnumbered white members eight to one.

Church Reopening and Challenges

Reverend Drayton reopened the parish church 11 years after the Civil War ended, on March 26, 1876. Worshippers came from Charleston by steamer to Bees Ferry and then walked to the church. Money for repairs likely came from selling land for phosphate mining along the Ashley River. This brought a short period of economic growth to the area. Ten years after reopening, the church was badly damaged by the Great Charleston Earthquake of 1886. The earthquake's center was just seven miles north of the church. As Reverend Drayton's health worsened, his black congregation took on new leadership. Magwood's Chapel, a main place of worship, was given its own name: St. Andrew's Church, Charleston County. It later became known as St. Andrew's Mission Church. John Grimké Drayton died on April 2, 1891.

The 1900s: Quiet Times and a New Start

A Historical Landmark

Reverend Drayton was not replaced, and the church became inactive for the next 57 years. The church leaders tried to maintain the building and keep out vandals. After three leaders died, the remaining ones gave control of the church to the Diocese of South Carolina in 1916. The diocese made needed repairs over many years. From 1923 to 1946, Rev. Wallace Martin held occasional services. The building became a historical curiosity. Many postcards showing the empty Old St. Andrew's were made during this time. In 1937, a cherub and decorative grapevines were added over the reredos as a wedding gift. In 1940, Old St. Andrew's was documented and photographed as part of a federal government program.

Reopening After World War II

With Old St. Andrew's closed, Episcopalians had started a new church, All Saints' Mission, closer to their homes. They wanted to build a new church, as reopening the old, damaged colonial church seemed too difficult. But they could not make a new church happen. So, they reluctantly reopened St. Andrew's Parish Church on Easter Day, March 28, 1948. Rev. Lawton Riley was named the priest in charge.

Soon after, termites were found in the church walls. The building was closed for repairs for almost two years. Old plaster was removed to get to the wooden parts. Damaged pews, window sills, and shutters were fixed. The reredos was cleaned, and the roof and outside trim were painted. An oil heater was installed. A memorial tablet from the 1700s was likely removed for the heater's chimney. Memorial tablets for John Grimké Drayton and Drayton Franklin Hastie were placed on the south and north walls. The first electric lighting was installed along the tops of the walls. Colonel William Izard Bull's plan of the pews he installed in 1855 was found on the north wall. Electricians who installed the lighting etched their names above it. Sadly, this historical drawing was covered by the Hastie memorial instead of being saved.

Paying for repairs was a constant challenge. The church's old land, the glebe, was sold. The church held many fundraisers. The most lasting one is the Tea Room. As ladies prepared the church for Sunday services in the spring, visitors going to see the Ashley River plantations would see cars parked. They would ask where they could eat, as there were no restaurants nearby. These clever women started bringing sandwiches, coffee, and desserts. They served visitors from their cars, then at picnic tables, and later in the parish house once it was built. A Gift Shop with handmade items and foods was added. The Tea Room and Gift Shop have been a regular event for over 70 years.

Growth and Challenges

Rev. Lynwood Magee arrived in 1952. He led the church during a time of huge growth in the 1950s and 1960s. During his time, the number of church members quadrupled. The church regained its full parish status in 1955. A simple concrete block parish house was built in 1953. It was then expanded twice (1956 and 1962) to fit the growing number of members and Sunday school students.

Reverend Magee left Old St. Andrew's in 1963. Four rectors followed him over the next 22 years. This period had less financial support due to people getting tired of donating, a lack of interest, and internal problems.

The church got a needed makeover in 1969. The outside walls were repaired and repainted. The inside walls and pews were painted light blue. The sandstone paver floor, which was set in dirt, had become uneven. When the floor was taken up, the 1764 paver and tile floor was found underneath. The old floor was more attractive and stronger. So, it was reset in its original pattern. A cross of St. Andrew (an X) was placed where the aisles crossed and at the west end.

The time of Rev. John Gilchrist (1970–81) brought new energy to the church. The front of the parish house was expanded to include a large seating area and a bigger kitchen. In 1973, Old St. Andrew's was placed on the National Register of Historical Places. It also celebrated 25 years since its 1948 reopening. Church members celebrated the national bicentennial by wearing old-fashioned clothes. Gilchrist guided the church through changes to the Book of Common Prayer. When the new book was used in 1979, some members left and started a new church nearby.

Renewed Confidence

The time of rector George Tompkins (1987-2006) brought much-needed stability. Just two years after he arrived, Hurricane Hugo hit Charleston. The hurricane spared the church building. However, it heavily damaged the parish house. It also knocked down over 200 trees in the churchyard and overturned gravestones. Cleaning up and repairing the buildings and grounds took over a year. The blue walls and pews of the church were repainted white. The education part of Magee House, built in 1963, was repaired. Paying for these projects was a constant financial challenge. In 1990, the main dining room of the parish house was named Gilchrist Hall. Two years later, the parish house was named Magee House. By the end of the 1990s, Old St. Andrew's had 701 members, 21 percent more than at the start of the decade.

The 2000s: Growth and New Beginnings

Big Restoration and 300th Anniversary

As the millennium approached, the church leaders planned for the church's 300th anniversary in 2006. Engineers were hired to check the building. What they found was worrying. The walls were tilting outward. The roof rafters from 1764 were too small, and some parts had pulled away. The walls were pushed out, in some places by eight inches. The effects of the 1886 earthquake were also visible. The report was serious: "the under-size rafters posed an immediate life safety concern."

The estimated cost for these and other repairs was $1.2 million. Donations from church members and outside groups covered about 40 percent. The rest was borrowed. The church was closed for about a year, starting in April 2004. Almost the entire building was restored. The church reopened on Easter Day 2005. This was 57 years after it reopened in 1948.

The church celebrated its 300th anniversary with a year of activities in 2005-2006. Reverend Tompkins, who had been battling rheumatoid arthritis, resigned in March 2006. Rev. Marshall Huey was chosen as the church's 19th rector. He was officially installed on November 5, 2006.

Church Life Today

The church's most urgent financial need was paying off the $729,000 restoration loan. They managed to do this in just six years. The relationship between Old St. Andrew's and St. Andrew's Mission Church (founded in 1845) grew stronger. This happened through talks between Rev. Huey and the ministers of St. Andrew's Mission. The first Easter Sunrise service was held at Drayton Hall with St. Andrew's Mission Church. This helped connect the churches to the wider West Ashley community. It later moved to Magnolia Plantation and Gardens, where it continues today. In 2008, a Family Service was started to appeal to families with young children. Missionary efforts expanded, including work in Boca Chica, Dominican Republic, and West Ashley. The Old St. Andrew's Trust was created to give the church long-term financial stability. In 2020, microphones and cameras were installed in the church. This allowed them to livestream worship services during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. In 2021, the education wing of Magee House was greatly renovated.

Church Group Affiliation

In 2012, Old St. Andrew's and other churches in the diocese faced legal issues. This happened after the Diocese of South Carolina separated from the Episcopal Church. After seven weeks of discussion in early 2013, members of Old St. Andrew's voted three to one to stay with the diocese and leave the national church. The parish's vote was similar to most of the diocese, as 80 percent eventually left the Episcopal Church. In 2017, the diocese, and with it Old St. Andrew's, joined the Anglican Church in North America (ACNA).

For 10 years, legal battles happened between the Episcopal Church and the churches that left. They argued over who owned the church properties. After many court decisions and appeals, on May 24, 2023, the South Carolina Supreme Court said that Old St. Andrew's owns its property, not the Episcopal Church.

Rectors

- Alexander Wood (1708-1710)

- Ebenezer Taylor (1712-1717)

- William Guy (1718-1750)

- Charles Martyn (1753-1770)

- Thomas Panting (1770-1771)

- Christopher Ernst Schwab (1771-1773)

- Thomas Mills (1787-1816)

- Joseph M. Gilbert (1824)

- Paul Trapier (1830-1835)

- Jasper Adams (1835-1838)

- James Stuart Hanckel (1841-1849, 1849-1851)

- John Grimké Drayton (1851-1891)

- Lynwood Cresse Magee (1955-1963)

- John L. Kelly (1963-1966)

- Howard Taylor Cutler (1967-1970)

- John Ernest Gilchrist (1970-1981)

- Geoffrey Robert Imperatore (1982-1985)

- George Johnson Tompkins III (1987-2006)

- Stewart Marshall Huey Jr. (2006-Present)

See also

- List of the oldest churches in the United States

- List of the oldest buildings in South Carolina

- List of parishes and parish churches in South Carolina

- St. Andrew's Mission Church (Charleston, South Carolina)

- John Grimké Drayton

- Magnolia Plantation and Gardens (Charleston, South Carolina)