Operation Ladbroke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Ladbroke |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Allied invasion of Sicily | |||||||

Sicily (pictured in red). |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 1st Airlanding Brigade | 385th Coastal Battalion 1st Battalion, 75th (Napoli) Infantry Regiment |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,075 | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 313 killed and 174 missing or wounded | unknown | ||||||

Operation Ladbroke was a special military mission during World War II. It involved British airborne troops who landed in Sicily, near Syracuse, using gliders. This happened on July 9, 1943, as part of a bigger plan called Operation Husky, which was the Allied invasion of Sicily.

This was the first time the Allied forces used so many gliders in one mission. The operation started from Tunisia. The British 1st Airlanding Brigade, led by Brigadier Philip Hicks, used 136 Hadrian gliders and eight Airspeed Horsa gliders. Their main goal was to land a large number of troops near Syracuse. They also needed to capture the Ponte Grande Bridge and then take control of Syracuse itself, especially its important docks. This was all to prepare for the main invasion of Sicily.

However, many gliders faced problems on their way to Sicily. Sixty-five gliders were released too early by their American towing planes and crashed into the sea. About 252 soldiers drowned. Out of all the gliders, only twelve landed exactly where they were supposed to. Only 87 men reached the Ponte Grande Bridge. Even with so few soldiers, they managed to capture the bridge. They held it for longer than expected, but eventually ran out of ammunition. With only fifteen soldiers left unharmed, they had to surrender to the Italian forces.

The Italians then tried to blow up the bridge. But the British soldiers from the 1st Airlanding Brigade had already removed the explosives. This stopped the Italians from destroying the bridge. Other British troops from the brigade landed in different areas of Sicily. They helped by cutting communication lines and capturing enemy gun batteries.

Contents

Why Sicily? The Background Story

By December 1942, Allied forces were winning the North African Campaign. They had landed in Tunisia a month earlier in Operation Torch. With victory in North Africa almost certain, the Allies started talking about their next big move. Many American leaders wanted to invade Northern France right away. But the British, along with Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower, thought the island of Sardinia would be a better target.

In January 1943, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt met at the Casablanca Conference. They decided to invade Sicily. Taking Sicily would help the Allies control shipping routes in the Mediterranean Sea. It would also give them airfields closer to mainland Italy and Germany.

The invasion of Sicily was given the codename Operation Husky. Planning for Husky began in February. At first, the British Eighth Army, led by General Sir Bernard Montgomery, was supposed to land on the southeastern part of Sicily. They would then move north to the port of Syracuse. Two days later, the U.S. Seventh Army, led by Lieutenant General George S. Patton, would land on the western part of the island. They would then move towards the port of Palermo.

Changes to the Invasion Plan

In March, it was decided that the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division and the British 1st Airborne Division would drop by parachute and glider. They would land just before the main sea landings. Their job was to land a few miles behind the beaches and stop the enemy defenders. This would help the Allied ground forces land safely.

However, in early May, these plans changed a lot. General Montgomery, the commander of the Eighth Army, insisted on new ideas. He argued that if Allied forces landed separately at opposite ends of the island, the enemy could defeat each army one by one. Instead, the new plan was for both the Eighth and Seventh Armies to land at the same time. They would land along a 100-mile stretch of coastline on Sicily's southeastern side.

The plans for the airborne divisions also changed. Montgomery believed that the airborne troops should land near Syracuse to capture its valuable port. Brigadier General Maxwell D. Taylor of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division also said that dropping behind the beaches was not a good idea for airborne troops. They were only lightly armed and could be hit by 'friendly fire' from Allied naval ships.

In the new plan, a strong group from the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division would parachute northeast of Gela. Their job was to stop enemy forces from reaching the Allied beachheads. The British 1st Airborne Division would carry out three large airborne operations. The 1st Airlanding Brigade, led by Brigadier Philip Hicks, would capture the Ponte Grande road bridge south of Syracuse. The 2nd Parachute Brigade would seize the port of Augusta. Finally, the 1st Parachute Brigade would take and secure the Primasole Bridge over the River Simeto.

Planning the Mission

There weren't enough transport planes for all three British brigades to do their missions at the same time. So, it was decided that Operation Ladbroke would go first. Its goal was to capture the Ponte Grande Bridge. This mission, led by Brigadier Philip Hicks, happened just before the main sea landings. It took place on the night of July 9. The other two operations would happen on the next two nights.

The 1st Airlanding Brigade also had other jobs. They needed to capture Syracuse harbor and the city area next to it. They also had to destroy or take over a coastal artillery battery. This battery could fire on the landing ships.

When training for the operation began, problems quickly appeared. The first plan for the airborne missions was to use parachutists for all three. But in May, Montgomery changed the plan. He decided that the troops sent to capture Syracuse would be better off using gliders. This would give them more firepower. His airborne advisor, Group Captain Cooper of the Royal Air Force, argued that a glider landing at night with inexperienced aircrews was too risky. But the decision stayed the same.

Montgomery's orders caused several issues, especially with the transport planes. The 51st Troop Carrier Wing was supposed to work with the British 1st Airborne Division. But this wing had almost no experience with gliders. The 52nd Troop Carrier Wing had much more glider experience, but they were already training for a parachute mission. Switching them would cause many problems. This meant the British 1st Airborne Division, and the 1st Airlanding Brigade, had to work with an inexperienced transport wing.

Glider Challenges

There were also problems with the gliders themselves and the pilots. Just a few months before the operation, there was a big shortage of working gliders in North Africa. In late March, some Waco gliders arrived, but they were in bad shape. Because of neglect and tropical weather, pilots could only put together a few of them.

More American gliders started arriving in North African ports on April 23. But they weren't ready to use right away. Their crates were unloaded in a messy way, instructions were often missing, and the people putting them together were new to the job. However, once the decision was made to use gliders for the 1st Airlanding Brigade, assembly improved. By June 12, 346 gliders were ready.

A small number of Horsa gliders were also brought to North Africa. Thirty of them flew about 1,500 miles from England in an operation called Turkey Buzzard. After facing attacks from Luftwaffe fighter planes and bad weather, 27 Horsas made it to North Africa in time for the operation.

Even when enough gliders arrived, they weren't all ready for training. On June 16, most gliders were grounded for repairs. On June 30, many of them had weak tail-wiring, which meant another three-day grounding. Because of these problems, the 51st Troop Carrier Wing couldn't do a large glider exercise until mid-June. They did some smaller exercises, but these were done in daylight, which wasn't realistic for a night mission.

The British glider pilots also caused problems. There were enough pilots, but they were very new to this. They were from the Glider Pilot Regiment and had no experience with Waco gliders or night operations. British rules had even said such operations were impossible. On average, the pilots had only eight hours of flight experience in gliders. Few were considered ready for combat, and none had fought in a battle before. Colonel George Chatterton, the head of the Glider Pilot Regiment, protested their involvement. He believed they were completely unfit for any mission. By the end of the training period, the glider pilots had only an average of 4.5 hours of training in the unfamiliar Waco gliders. This included only 1.2 hours of night flying.

British 1st Airlanding Brigade

The 1st Airlanding Brigade included:

- the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment

- 181st (Airlanding) Field Ambulance (medical unit)

- 9th Field Company, Royal Engineers (engineers)

The Staffords were given the job of securing the bridge and the area to the south. The Borders were to capture Syracuse. For the mission, the 1st Airlanding Brigade was given 136 Waco gliders and eight Horsa gliders. Waco gliders could only carry fifteen soldiers, half as many as the Horsa. This meant the whole brigade couldn't be deployed.

Six of the Horsas, carrying 'A' and 'C' companies from the Staffords, were planned to land at the bridge at 11:15 PM on July 9. This was a surprise attack. The rest of the brigade would arrive at 1:15 AM on July 10. They would land in areas between 1.5 and 3 miles away, then move to the bridge to help defend it.

Italian Defenders

The Ponte Grande Bridge was just outside the area defended by the Italian 206th Coastal Division. This division would also fight against the British sea landing. The fortress commander was Rear Admiral Priamo Leonardi, with Colonel Mario Damiani leading the army part.

The Augusta-Syracuse Naval Fortress Area, which included the Coastal Division, had many defenses. It had six medium and six heavy coastal artillery batteries. There were also eleven other batteries that could be used against both ships and aircraft. Six batteries were only for anti-aircraft guns. Finally, the Fortress had an armored train with four 120 mm guns. The army part included the 121st Coastal Defence Regiment, which had four battalions. Naval and air force battalions were also available. The 54th Infantry Division "Napoli" could send more soldiers if needed.

The Mission Begins

On July 9, 2,075 British troops, along with seven jeeps, six anti-tank guns, and ten mortars, boarded their gliders in Tunisia. They took off at 6:00 PM, heading for Sicily. Before the landing, twelve Boeing B-17s and six Vickers Wellingtons flew along the coast. They used radar jamming devices. Between 9:00 PM and 9:30 PM, 55 Wellingtons bombed the port and airport of Syracuse. This caused casualties, including the Italian naval base commander. To confuse the Italian defenders, 280 puppets dressed as paratroopers were dropped north of the landing area.

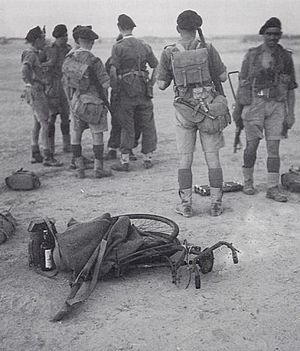

On their way, the gliders faced strong winds and poor visibility. They were also shot at by anti-aircraft guns. To avoid the gunfire and searchlights, the pilots of the towing planes flew higher or took sudden turns. In the confusion, some gliders were released too early. Sixty-five of them crashed into the sea, and about 252 men drowned.

Of the remaining gliders, only twelve landed in the correct spot. Another fifty-nine landed up to 25 miles away. The rest were either shot down or failed to release and returned to Tunisia. About 200 American paratroopers were mistakenly dropped in the British area. They were captured by Italian forces early on July 10.

Only one Horsa glider, carrying a group of soldiers from the Staffords, landed near the bridge. Its commander, Lieutenant Withers, split his men into two groups. One group swam across the river and took a position on the other side. Then, they attacked the bridge from both sides at once and captured it. The Italian defenders left their pillboxes on the north bank.

The British soldiers then removed some explosives that had been placed on the bridge. They dug in and waited for more troops or relief. Another Horsa landed about 200 yards from the bridge but exploded on landing, killing everyone inside. Three other Horsas carrying the surprise attack team landed within 2 miles of the bridge. Their occupants eventually found their way to the bridge. More soldiers started to arrive at the bridge, but by 6:30 AM, there were only eighty-seven men.

Elsewhere, about 150 men landed at Cape Murro di Porco and captured a radio station. The previous Italian occupants of the station had sent a warning about glider landings. Based on this, the local Italian commander ordered a counter-attack. But his troops did not get his message. The scattered landings actually helped the Allies. They were able to cut all telephone wires in the immediate area.

The glider carrying the brigade's second-in-command, Colonel O. L. Jones, landed next to an Italian coastal artillery battery. At daylight, the staff officers and radio operators attacked and destroyed the battery's five guns and their ammunition storage. Other small groups of Allied soldiers tried to help their comrades. They attacked Italian defenses and targeted enemy reinforcements. Another attack by a group of paratroopers on three Italian coastal batteries failed. These batteries were then able to fire on Allied landing craft and troops at 6:15 AM on July 10. At 9:15 AM, the 1st Battalion of the Italian 75th Infantry Regiment captured another 160 American paratroopers. Another group of paratroopers attacked an Italian patrol. The Italian commander was killed, and his unit became disorganized. This meant they couldn't help fight against British tanks near the bridge later.

The first counterattack on the bridge came from two companies of Italian sailors. The British pushed them back. As the Italians reacted to the Allied landings, they gathered more troops. They also brought up artillery and mortars to shell the British-controlled Ponte Grande Bridge. The British defenders were under attack, and the expected relief from the British 5th Infantry Division did not arrive at 10:00 AM as planned.

At 11:30 AM, the Italian 385th Coastal Battalion arrived at the bridge. Soon after, the 1st Battalion, 75th (Napoli) Infantry Regiment, also arrived. The Italians were ready to attack the bridge from three sides. By 2:45 PM, only fifteen British troops defending the bridge were still unharmed (four officers and eleven soldiers). At 3:30 PM, with no ammunition left, the British stopped fighting. Some men on the south side of the bridge escaped into the countryside, but the rest became prisoners of war.

With the bridge back in Italian hands, the first unit from the 5th Infantry Division arrived at 4:15 PM. This was the 2nd Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers. They launched a successful counter-attack. This was possible because the demolition charges had been removed from the bridge earlier, preventing the Italians from destroying it. The 1st Battalion of the 75th Infantry Regiment had no artillery. They could not fight against the British tanks and had to retreat after losing many soldiers.

The remaining soldiers from the 1st Airlanding Brigade did not fight anymore. They were sent back to North Africa on July 13. During the landings, the 1st Airlanding Brigade suffered the most losses of all British units involved. A total of 313 soldiers were killed, and 174 were missing or wounded. Fourteen glider pilots were killed, and eighty-seven were missing or wounded.

What Happened Next: Aftermath

After an investigation into the problems with the airborne missions in Sicily, the British Army and Royal Air Force made new recommendations.

- Aircrews would be trained in both parachute and glider operations.

- Pathfinders (special troops who mark landing zones) would land before the main force to set up their beacons.

- The landing plan was made simpler. Whole brigades would land on one large drop zone, instead of smaller areas for each battalion.

- Gliders would no longer be released at night while still over water.

- Their landing zones would be large enough for the aircraft to land with extra space.

After an incident where Allied ships accidentally fired on Allied planes, ship crews received more training in recognizing aircraft. Allied aircraft were also painted with three large white stripes to make them easier to identify. Training for pilots of the Glider Pilot Regiment was increased. Improvements were also made to the gliders, including better communication between aircraft.

To find another way to deliver jeeps and artillery by air, the Royal Air Force started experimenting with parachutes. They tried dropping jeeps and guns from aircraft bomb bays. A second Royal Air Force transport group, No. 46, was formed. This group used only Douglas Dakotas, instead of a mix of aircraft like No. 38 Group. Together, the Royal Air Force groups could provide 362 planes for transport.