Otto Struve facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Otto Struve

|

|

|---|---|

Struve on a 1949 US Post envelope

|

|

| Born |

Отто Людвигович Струве

August 12, 1897 Kharkiv, Sloboda Ukraine, then Russian Empire (now Ukraine)

|

| Died | April 6, 1963 (aged 65) Berkeley, California, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Kharkiv University |

| Known for | Doppler spectroscopy Struve–Sahade effect |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society Henry Norris Russell Lectureship (1957) Henry Draper Medal (1949) Bruce Medal (1948) Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1944) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

Otto Struve (born August 12, 1897 – died April 6, 1963) was an important astronomer. He was born in Russia but spent most of his life and scientific career in the United States. His full Russian name was Otto Lyudvigovich Struve.

Otto came from a famous family of astronomers called the Struve family. His father was Ludwig Struve, his grandfather was Otto Wilhelm von Struve, and his great-grandfather was Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve. He was also the nephew of Karl Hermann Struve.

Struve wrote over 900 articles and books about space. This made him one of the most active astronomers in the mid-1900s. He led several major observatories, including Yerkes Observatory and McDonald Observatory. He helped these observatories become world-famous. He also hired brilliant scientists like Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar and Gerhard Herzberg, who later won Nobel Prizes.

Struve mainly studied binary stars (two stars orbiting each other) and variable stars (stars that change brightness). He also looked at how stars spin and the gas and dust between stars, known as interstellar matter. He was one of the few famous astronomers before the Space Age who believed that alien life was common. He was an early supporter of searching for life beyond Earth.

Contents

Early Life in Russia

Otto Struve was born in 1897 in Kharkiv, which is now in Ukraine. He was the first child of Ludwig and Elizaveta Struve. His father was part of the large Struve family, who were well-known Baltic Germans in Russia.

Otto started learning about astronomy very early. From age eight, he went with his father to the telescope tower. By age 10, he was already doing small observations, even though he was afraid of dark places. At 12, he started school in Kharkiv and showed a great talent for math. Otto was the first child in his family in Russia to go to a Russian-speaking school instead of a German one. He spoke both German and Russian.

After finishing school in 1914, he continued his astronomy work. In June 1914, he helped prepare for a total solar eclipse. He later used this experience for his master's degree work at Kharkiv University in 1919.

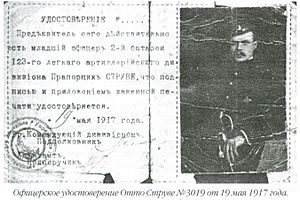

Struve started at Kharkiv University in 1915. Russia was going through a lot of political problems and wars then. In early 1916, he paused his studies and joined a military artillery school. He quickly finished his training and was sent to the Turkish front in February 1917.

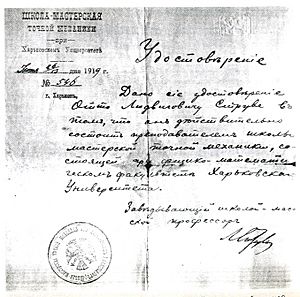

After a peace treaty was signed, Struve returned to Kharkiv for a year. He finished his university course in June 1919. He received a certificate saying he would stay at the university to become a professor of astronomy. During this time, he also worked at a school for precision mechanics. He got a license as a workshop trainer. His father had started this workshop to train astronomy engineers in Russia.

Moving to the United States

Because of his German background and his military service with the White Russian Army, Otto's family faced danger from the Bolsheviks. They had to move from Kharkiv to Sevastopol, which was still controlled by the White Army. There, many sad things happened to his family. His youngest sister drowned, his brother died from tuberculosis, and his father died from a stroke in November 1920.

While his mother and sister went back to Kharkiv, Otto escaped from Sevastopol to Turkey on a military transport. He never returned to Russia. He was invited to conferences in the Soviet Union later, but he always chose not to go.

For about a year and a half, Otto lived as a poor refugee in Turkey. He ate at relief agencies and took any job he could find. He even worked as a woodcutter. One night, lightning struck a tent near his, killing everyone inside. Otto wrote to his uncle in Germany for help, not knowing his uncle had already passed away. However, his uncle's wife contacted Paul Guthnick, who worked at the Berlin Observatory.

Germany was also struggling after the wars, so it was hard to find a job there for a Russian. Guthnick then wrote to Edwin B. Frost, the director of Yerkes Observatory in the U.S., asking if Struve could get a job. Frost replied, promising to help. In March 1921, Frost offered Struve a job at Yerkes. It was a very lucky chance for Struve to get this letter in his difficult situation in Turkey.

Struve accepted the offer. He wrote back in English, but his grammar showed he wasn't very good at the language yet. Frost was very impressed by Struve's family history in astronomy. He believed Struve would be a great scientist. It took several months to get his travel papers and money. In late August 1921, Struve got his visa. He boarded a ship in September and arrived in New York on October 7, 1921. Two days later, he reached Chicago.

Life in the United States

In late 1921, Struve started working at Yerkes Observatory. He was an assistant studying stellar spectroscopy and earned $75 a month. He began by taking a training course. The observatory was not doing very well, and Struve was often the only student in his class. He learned quickly by reading, practicing, and talking with professors.

Struve was a very talented scientist. Just five months after arriving, he discovered a pulsating star at Gamma Ursae Minoris. He wrote an article about it in September 1922. He spent more time observing than anyone else at Yerkes. He used every telescope available and even made weather observations. In October 1922, he discovered the asteroid 991 McDonalda, and in November, he found another asteroid, 992 Swasey.

In December 1923, Struve earned his PhD from the University of Chicago. His thesis was about short-period double stars. Frost helped him skip some required exams, saying Struve already knew a lot from his studies in Russia. Struve quickly moved up, becoming an instructor in 1924, an assistant professor in 1927, and a full professor in 1932.

From 1932 to 1947, Struve led Yerkes Observatory. He also helped start and direct the McDonald Observatory from 1939 to 1950. Later, from 1952 to 1962, he was the first director of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. He stayed in America during these years, except for conferences and an eight-month break to study at the University of Cambridge in England. He won a Guggenheim Fellowship to pay for his trip. In Cambridge, he mostly studied interstellar matter.

Struve was a very successful leader. He made Yerkes Observatory famous and improved the astronomy department at the University of Chicago. He hired many young and talented researchers who became world-famous scientists. These included Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1983) and Gerhard Herzberg (who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1971). He also invited leading European scientists after World War II.

Hiring foreign scientists was difficult because some officials worried about Americans losing jobs during the Great Depression. Struve worked very hard to defend and justify each hiring. These efforts helped build a strong scientific team at Yerkes and Chicago University. For example, Chandrasekhar spent his whole career at Chicago University. He helped Struve and later took over as president of the American Astronomical Society.

By the late 1940s, many of the young researchers Struve hired had become established scientists. This sometimes caused tension, as they wanted to follow their own paths. In 1947, Struve left his role as director of Yerkes Observatory. He became chairman of the astronomy department at Berkeley and director of the Leuschner Observatory. One reason for his move was that he was tired of all the paperwork. At Berkeley, he spent more time on his own research and with students.

Research and Discoveries

In 1937, Struve discovered something called the Struve-Sahade effect. This effect means that the light from one star in a massive binary system appears weaker when that star is moving away from us. This makes it harder to study these stars accurately. In the same year, he also found ionized hydrogen gas between stars.

By 1959, Struve had published over 900 articles and books. This made him one of the most productive astronomers ever. Many of his writings helped make astronomy popular. He wrote many articles for magazines like Popular Astronomy and Sky and Telescope. He also reviewed many books and works by other astronomers.

Most of his scientific articles were co-written with Pol Swings. They focused on studying the light patterns (spectra) of unusual stars. Struve once said he could always find something interesting to study in a star's spectrum.

One of Struve's biggest discoveries was finding out that stars spin. He also found that the speed at which stars spin depends on their type and temperature. These discoveries helped scientists understand how stars develop over time. He also studied how electric fields affect the light from stars, causing their spectral lines to broaden. He researched the movement of gas in stellar atmospheres and expanding shells around stars.

To study these topics, he needed a larger telescope. So, between 1933 and 1939, he built an 82-inch telescope at the McDonald Observatory. At that time, it was the second-largest telescope in the world.

Beliefs About Alien Life

Struve believed that life and intelligence were common throughout the Universe. This idea came from his studies of slow-spinning stars. Many stars, including our Sun, spin much slower than scientists expected. Struve thought this was because these stars were surrounded by planets. These planets would have taken away much of the stars' original spinning energy.

Because so many stars spin slowly, Struve estimated in 1960 that there could be as many as 50 billion planets in our own Milky Way Galaxy alone.

Personal Life and Later Years

Otto Struve had a younger brother and two sisters. Sadly, all of them died young in Russia. His mother moved to the U.S. in January 1925 after Otto arranged her visa. She even started working in astronomy in the U.S., helping with measurements. She lived with Otto even after he got married.

On May 25, 1925, Struve married Mary Martha Lanning. She was a musician but worked as a secretary at Yerkes. They did not have any children, which meant the famous Struve astronomy family line ended with Otto.

On October 26, 1927, Struve became a U.S. citizen. By then, he spoke and wrote English very well, but he always kept a slight German accent. Even after marriage, Struve continued to work day and night. His wife, who was not a scientist, found this hard to accept. Their relationship became distant in later years.

Struve's health got worse in the late 1950s. He suffered from hepatitis, an illness he first got in Russia and Turkey. In 1956, he had a bad fall while using a telescope, breaking ribs and cracking vertebrae. He was in the hospital for about two months. He was permanently hospitalized around 1963 and died on April 6, 1963, in Berkeley. His mother and wife survived him. His mother died in 1964, and his wife died in 1966.

In 1925, Struve met his cousin, the astronomer Georg Hermann Struve. In the 1930s, they met again and studied the complex star system Zeta Cancri, using observations made by their grandfather.

Personal Qualities

People often described Struve as a big and serious man. He was about six feet tall and had gray hair and eyes. Struve was known for being very determined and demanding, both of himself and others. These were qualities that ran in his family. He was usually the first to arrive at the observatory and often worked late into the night. He would then spend nights using the telescope. People said he had only one goal: to advance astronomy as much as possible. Because of this, Struve often worked too much, had trouble sleeping, and sometimes looked tired after only a few hours of rest.

Struve was not always the best teacher. He missed many lectures because he was so busy with research and travel. Students had to do their own research when he was away. However, he still expected very high standards from them in exams. Even so, his passion for astronomy inspired many students.

Even though he didn't care much about himself, Struve cared about other people. His first paper published in Russian was about helping Russian scientists. The Russian Civil War caused a lot of suffering for scientific families in Russia. Struve and some colleagues formed a "Committee for Relief of Russian Astronomers." They organized sending food and clothing packages to help.

During the Great Depression, he worried about hiring foreign scientists when many Americans were jobless.

Awards and Honors

Struve received many important awards for his work. These include the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1944), the Bruce Medal (1948), the Henry Draper Medal (1949), and the Henry Norris Russell Lectureship (1957). His Royal Society medal was the fourth and last one received by a Struve family member.

The asteroid 768 Struveana was named in honor of his relatives. A crater on the Moon was named for three astronomers from the Struve family: Friedrich Georg Wilhelm, Otto Wilhelm, and Otto himself. The 82-inch telescope at McDonald Observatory, which Struve used, was named after him in 1966. The asteroid 2227 Otto Struve was named after him in 1955.

From 1932 to 1947, Struve was the Editor in Chief of the Astrophysical Journal. He was also president of the American Astronomical Society from 1946 to 1949. He served as vice-president (1948–1952) and then president (1952–1955) of the International Astronomical Union. In 1954, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society. He also received honorary degrees from nine universities.

See also

In Spanish: Otto Struve para niños

In Spanish: Otto Struve para niños

- Strömgren sphere

Images for kids

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |