Periodontal disease facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Periodontal disease |

|

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Gum disease, pyorrhea, periodontitis |

|

|

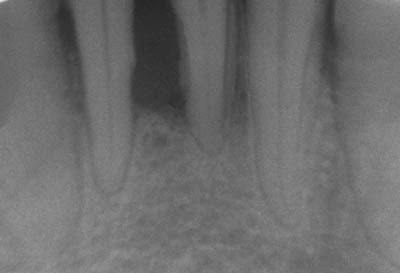

| Radiograph showing bone loss between the two roots of a tooth (black region). The spongy bone has receded due to infection under tooth, reducing the bony support for the tooth. | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Symptoms | Red, swollen, painful, bleeding gums, loose teeth, bad breath |

| Complications | Tooth loss, gum abscess |

| Usual onset | Getting gingivitis |

| Causes | Bacteria related plaque build up |

| Risk factors | Smoking, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, certain medications |

| Diagnostic method | Dental examination, X-rays |

| Treatment | Good oral hygiene, regular professional cleaning |

| Frequency | 538 million (2015) |

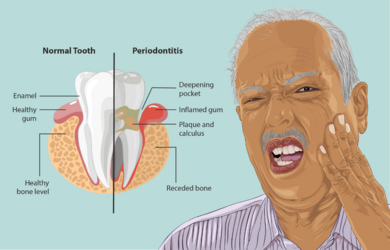

Periodontal disease, also known as gum disease, is a common problem that affects the tissues around your teeth. It starts with an early stage called gingivitis. Here, your gums become red and swollen, and they might bleed easily.

If gingivitis isn't treated, it can get worse and become periodontitis. This is a more serious form of gum disease. Your gums can pull away from your teeth, and the bone that holds your teeth in place can start to disappear. This can make your teeth loose or even cause them to fall out. You might also notice bad breath.

Gum disease is usually caused by bacteria in your mouth. These bacteria infect the tissues around your teeth. Things that can increase your risk include smoking, diabetes, and certain medications. Dentists diagnose gum disease by checking your gums and taking X-rays to look for bone loss.

The best way to treat gum disease is to practice good oral hygiene. This means daily brushing and flossing. Regular professional teeth cleanings are also very important. Sometimes, dentists might suggest antibiotics or even dental surgery. Quitting smoking and eating a healthy diet can also help your gums stay healthy. In 2015, about 538 million people worldwide were affected by gum disease.

What are the Signs of Gum Disease?

In its early stages, gum disease often has very few signs. Many people don't even know they have it until it's quite advanced.

Here are some things to look out for:

- Your gums might be red or bleed when you brush your teeth. This can also happen when you use dental floss or bite into hard foods like apples.

- Your gums might swell up and then go down, only to swell again.

- You might spit out blood after brushing your teeth.

- You could have bad breath or a metallic taste in your mouth that doesn't go away.

- Your gums might pull back, making your teeth look longer. This is called gingival recession.

- You might notice deep spaces, called "pockets," between your teeth and gums. These pockets form as the disease destroys the tissue holding your teeth.

- In later stages, your teeth might become loose.

It's important to know that gum inflammation and bone damage are usually not painful. So, if your gums bleed without pain, don't ignore it. It could be a sign of gum disease getting worse.

How Gum Disease Affects Your Body

Gum disease can lead to more inflammation throughout your body. This is shown by higher levels of certain proteins in your blood. It's also linked to a higher risk of serious health problems like stroke and heart attacks.

It can also be connected to atherosclerosis, which is when your arteries harden. For people over 60, gum disease has been linked to problems with memory and math skills.

People with diabetes often have worse gum inflammation. This can make it harder for them to control their blood glucose levels. This is because the constant inflammation from gum disease affects their whole body.

Diabetes and Gum Disease

Studies show a clear link between high blood sugar levels and gum disease. If someone has uncontrolled diabetes, their risk of getting or worsening gum disease is much higher.

In uncontrolled diabetes, harmful substances can damage cells in the gums and surrounding tissues. This can speed up the destruction of tissues around the teeth, leading to gum disease.

Oral Cancer and Gum Disease

Some research suggests a link between gum disease and oral cancer. People with advanced gum disease often have higher levels of body-wide inflammation. This type of inflammation is also linked to oral cancer.

Both gum disease and cancer can be influenced by your genes. It's possible that some people are more likely to get both diseases due to shared genetic factors. More research is needed to fully understand this link.

Other Body-Wide Effects

Gum disease can cause higher levels of inflammatory markers in your body. These markers are also linked to heart disease and strokes.

Bacteria from deep gum pockets can enter your bloodstream when you chew or brush your teeth. This might trigger or worsen a stroke. Gum disease can also contribute to atherosclerosis, where fatty plaques build up in your blood vessels. If these plaques break off, they can travel to the brain and cause a stroke.

Gum disease is also linked to various heart conditions. Higher inflammation can lead to the hardening of arteries and problems with heart rhythm. Studies in animals have shown a link between gum disease, stress on the body's cells, and heart stress.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, gum disease was linked to a higher risk of severe COVID-19 complications. This included needing intensive care, assisted breathing, and even death.

What Causes Gum Disease?

Gum disease is an inflammation of the periodontium. These are the tissues that support your teeth. The periodontium includes four main parts:

- The gingiva, or gum tissue.

- The cementum, which is the outer layer of the tooth roots.

- The alveolar bone, which are the bony sockets holding your teeth.

- The periodontal ligaments (PDLs), which are fibers that connect the tooth root to the bone.

The main cause of gingivitis is not cleaning your teeth well. This leads to a sticky film of bacteria and fungi called dental plaque building up at the gum line. Other things that contribute include poor nutrition and health problems like diabetes. If you have diabetes, it's extra important to take good care of your teeth.

In some people, gingivitis gets worse and turns into periodontitis. This happens when the gum tissues pull away from the tooth, forming a deep space called a periodontal pocket. Bacteria then grow in these pockets, causing more inflammation and bone loss. Things like rough dental fillings or teeth that are too close together can also trap plaque and lead to gum disease.

Smoking is another major factor that increases your risk of gum disease. It can also make treatment less effective. Smokers tend to have more bone loss and tooth loss than non-smokers. This is because smoking affects your body's ability to fight off infections and heal.

Rare genetic conditions like Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome can also increase the risk of gum disease.

If plaque isn't removed, it hardens into calculus, also known as tartar. Tartar above and below the gum line must be removed by a dental professional. While bacteria are the main cause, other factors play a role. Your genes can make you more likely to get gum disease. Conditions like Down syndrome and diabetes also increase your risk.

Stress might also be linked to gum disease. People from lower income backgrounds tend to have gum disease more often.

Your genes can influence your risk. Some people with good oral hygiene still get severe gum disease, while others with poor hygiene don't. This might be due to genetic factors that affect your immune system. For example, some people produce more inflammatory chemicals, leading to a stronger immune response that can damage tissues.

Diabetes makes gum disease worse. This is true for both type 2 and type 1 diabetes. The risk increases a lot if your blood sugar is not well controlled. Scientists are still learning exactly how diabetes affects gum disease, but it involves inflammation and how your immune system works.

How Gum Disease Develops

When dental plaque builds up on your teeth, especially near and under the gums, the normal balance of bacteria in your mouth changes. Scientists are still figuring out exactly which bacteria cause the most harm. However, certain types of bacteria and viruses are often involved.

Plaque can be soft or hard (calcified). The calcium that hardens plaque on your teeth comes from your saliva. Under the gum line, it comes from the fluid that oozes from inflamed gums.

The damage to your teeth and gums actually comes from your own immune system. Your body tries to fight off the microbes that are causing problems. This fight can accidentally destroy bone and ligaments that support your teeth. So, while bacteria start the disease, your body's strong immune response causes much of the damage.

Types of Gum Disease

There have been several ways to classify gum diseases over the years. Here's a simplified look at some common types:

- Gingivitis: This is the mildest form, where gums are inflamed but there's no bone loss yet.

- Chronic periodontitis: This is a common type where gums are inflamed, and there's gradual bone loss.

- Aggressive periodontitis: A less common but faster-progressing form of gum disease.

- Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis/periodontitis: These are severe forms where gum tissue dies, often seen in people with weakened immune systems.

- Abscesses of the periodontium: These are painful pus-filled infections in the gums.

Dentists also describe gum disease by how much of your mouth is affected (localized or generalized) and how severe the damage is.

How Severe is It?

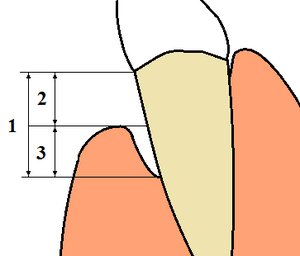

The "severity" of gum disease refers to how much of the tissue holding your teeth has been lost. This is measured in millimeters.

- Slight: 1 to 2 mm of tissue loss.

- Moderate: 3 to 4 mm of tissue loss.

- Severe: 5 mm or more of tissue loss.

How Much is Affected?

The "extent" of the disease describes how many teeth or areas in your mouth are affected. Dentists check six spots around each tooth.

- If up to 30% of the spots are affected, it's called "localized."

- If more than 30% are affected, it's called "generalized."

Preventing Gum Disease

Good daily oral hygiene is key to preventing gum disease:

- Brush your teeth properly: Brush at least twice a day. Try to angle your toothbrush bristles slightly under the gum line to clean thoroughly. This helps remove bacteria and plaque.

- Floss daily: Use dental floss every day to clean between your teeth. If you have bigger spaces, you can use interdental brushes. Don't forget to clean behind your back teeth too!

- Use antiseptic mouthwash: Some mouthwashes, like those with Chlorhexidine gluconate, can help reduce gingivitis when used with good brushing and flossing. However, they can't fix bone loss from periodontitis.

- Regular dental check-ups: Visit your dentist or dental hygienist regularly for check-ups and professional cleanings. They can check your oral hygiene, look for early signs of gum disease, and clean areas you might miss.

During a professional cleaning, dental hygienists use special tools to clean under your gum line. This helps remove plaque and tartar and stops gum disease from getting worse. After a cleaning, plaque can grow back in about three to four months. That's why your daily home care is so important. Without good daily hygiene, gum disease will likely return, especially if you've had it before.

Treating Gum Disease

The most important part of treating gum disease is having excellent oral hygiene at home. This means brushing twice a day and flossing daily. Using an interdental brush can also help if you have space between your teeth.

If you have trouble brushing well, like if you have arthritis, you might need more frequent professional cleanings or a powered toothbrush. It's important to understand that gum disease is a long-term problem. You'll need a lifelong routine of great home care and regular visits to your dentist or periodontist (a gum specialist) to keep your teeth healthy.

First Steps in Treatment

To get your gums healthy, the first step is to remove plaque and tartar. This is done with a non-surgical procedure called "root surface instrumentation" (RSI). This process disturbs the bacterial film under your gum line.

Special tools are used to scrape away plaque and tartar from below the gum line. This might take several visits and sometimes requires local anesthesia to make it comfortable. Your dentist might also adjust your bite if too much force is being put on teeth with less bone support. Any rough fillings or gaps between teeth that trap plaque might also need to be fixed. RSI focuses on removing tartar, which is enough for healing.

Checking Progress

Non-surgical cleaning usually works well if the gum pockets are not too deep (less than 4-5 mm). Your dentist or hygienist will check your gums four to six weeks after the initial cleaning. They'll see if your home care has improved and if the inflammation has gone down.

If pockets deeper than 5-6 mm remain and still bleed, it means the disease is still active. This will likely lead to more bone loss over time. This is especially true for molar teeth where the areas between the roots are exposed.

When Surgery is Needed

If non-surgical treatment doesn't stop the disease, your dentist might suggest dental surgery. The goal of surgery is to remove tartar completely and fix any bone problems caused by the disease. This helps reduce the depth of the gum pockets.

Many surgical methods exist, including cleaning under the gum flap and reshaping bone. Long-term studies show that surgery, combined with regular follow-up care, can be very successful in preventing further tooth loss in most people with moderate to advanced gum disease.

Local Medications

Sometimes, dentists can apply medicine directly into the gum pockets. This is called local drug delivery. It's often preferred over taking pills because it has fewer side effects and reduces the risk of bacteria becoming resistant to the medicine. For example, local application of certain medications like tetracycline or statin can help.

Systemic Medications

In some cases, your dentist might prescribe antibiotics that you take by mouth. These help reduce the overall amount of bacteria in your mouth. However, there's not much strong evidence that these antibiotics make a big difference in the long run compared to just cleaning. Also, using too many antibiotics can lead to bacteria becoming resistant.

Ongoing Care

Once your gum disease has been successfully treated, whether with or without surgery, you'll need ongoing "periodontal maintenance." This means regular check-ups and thorough cleanings, usually every three months. This helps prevent the harmful bacteria from growing back and allows your dentist to catch any signs of the disease returning early.

If your brushing habits don't improve, gum disease is likely to come back.

Other Treatments

Some at-home treatments involve putting antimicrobial solutions, like hydrogen peroxide, into gum pockets. This can help reduce infections and inflammation if used daily. However, these treatments don't remove tartar, so the bacteria can quickly grow back.

A low dose of Doxycycline might be prescribed along with cleaning. This medication can help by stopping enzymes that break down the tissues supporting your teeth. Only small doses are used to avoid harming helpful mouth bacteria.

What to Expect (Prognosis)

Dentists use a tool called a periodontal probe to measure gum disease. This thin "measuring stick" is gently placed into the space between your gums and teeth.

- If the probe goes 3 mm or less below the gum line, you can usually clean this area well at home with a toothbrush.

- If the probe goes deeper than 3 mm, it's called a "pocket." You won't be able to clean these deeper pockets well at home. You'll need professional cleanings.

- If pockets reach 6 to 7 mm deep, even dental professionals might struggle to clean them completely. In such cases, surgery might be needed to reduce the pocket depth or reshape the gums and bone. This helps you clean the area better at home.

If you have pockets 7 mm or deeper, you're at risk of losing those teeth over time. If this problem isn't found and treated, your teeth might gradually become loose and eventually need to be removed, sometimes due to infection or pain.

Studies have shown that without any oral hygiene, about 10% of people will get severe gum disease with rapid tissue loss. About 80% will have moderate loss, and 10% will not experience any loss.

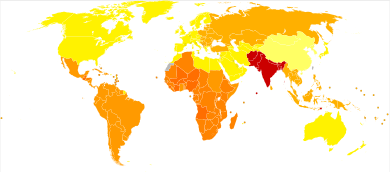

How Common is Gum Disease?

Gum disease is very common. It's considered the second most common dental disease worldwide, after dental decay (cavities). In the United States, about 30-50% of people have some form of gum disease, but only about 10% have severe cases.

In 2010, about 750 million people, or 10.8% of the world's population, had chronic gum disease.

Gum disease tends to be more common in areas or populations with less access to good hygiene and healthcare. It's less common in places with a higher standard of living. People from lower income backgrounds are often affected more than those from higher income backgrounds.

History of Gum Disease

Evidence shows that ancient humans had gum disease millions of years ago. Records from China and the Middle East, along with archaeological studies, prove that gum disease has affected people for thousands of years.

Research on ancient plaque DNA shows that hunter-gatherers had less gum disease. However, it became more common when people started eating more grains. The famous Otzi Iceman was found to have had severe gum disease. Interestingly, studies suggest that people in the Roman era in the UK had less gum disease than people today. Researchers think smoking might be a key reason for this difference.

Word Origins

The word "periodontitis" comes from Greek words. "Peri" means "around," and "odous" (odontos) means "tooth." The ending "-itis" means "inflammation." So, periodontitis means "inflammation around the tooth."

The word "pyorrhea" (or pyorrhoea) also comes from Greek. "Pyorrhoia" means "discharge of matter." "Pyon" means "discharge from a sore," and "rhoē" means "flow." So, pyorrhea means a "flow of pus." This term can describe any pus discharge, not just from the teeth.

Images for kids

-

Radiograph showing bone loss between the two roots of a tooth (black region). The spongy bone has receded due to infection under tooth, reducing the bony support for the tooth.

See also

In Spanish: Periodontitis para niños

In Spanish: Periodontitis para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |