Proto-city facts for kids

A proto-city was a very large and busy settlement from the Neolithic (New Stone Age) period. It was like a big village but not quite a full city. What made it different from a real city was that it didn't have clear plans or a strong central government telling everyone what to do. Some famous examples of proto-cities include Jericho, Çatalhöyük, and the huge sites of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture. Places from the Ubaid period in Mesopotamia were also proto-cities. These settlements existed before the first true cities, like Uruk, appeared in Mesopotamia around 3000 BC. The way cities grew from these early settlements wasn't always the same. This big change from hunting and gathering to agriculture and settled life is called the Neolithic Revolution.

Contents

What is a Proto-City?

Proto-cities were huge and densely populated places for their time. But they didn't have many features we see in later cities, like those in Mesopotamia around 3000 BC. These later cities had many people living close together, often with different social groups. They also had strong leaders who organized big building projects, shared food, and sometimes led raids.

In contrast, proto-cities like Çatalhöyük had many people but didn't show clear signs of central control or different social groups. For example, they didn't have huge public buildings that would need a strong leader to organize.

Famous Proto-Cities

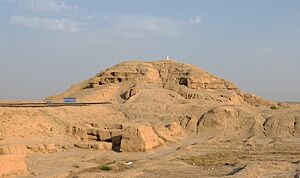

Jericho: An Early Settlement

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A Jericho was a large settlement with many people living there as early as 9000 BC. Some experts think between 200 and 3000 people lived there. It was close to fresh water from the spring at Ain es-Sultan. This helped people start animal husbandry (raising animals) and agriculture (farming) very early. This made Jericho one of the most advanced places during the Neolithic Revolution in the Fertile Crescent.

The settlement covered about 2 or 3 hectares. Its most famous parts were stone walls 3 meters wide and 4 meters tall. It also had the oldest known large building, the Tower of Jericho. This stone tower was 8 meters high and was built around 8000 BC. Building the Tower took a lot of teamwork, possibly 10,400 days of work!

The Tower might have been part of a defense system or a way to detect floods. It could also have been a special monument to encourage people to live and work together. Some think it might show that certain people or groups had power. Evidence of fighting has been found, with skeletons of twelve people inside the tower. This shows that even with new farming and building skills, how people organized themselves was very important. Around 6000 BC, a big earthquake likely stopped the spring, ending Neolithic Jericho.

Çatalhöyük: A Unique Village

Çatalhöyük was a huge Neolithic site in Southern Anatolia. People lived there from 7100 to 6000 BC. At its peak, up to 8000 people lived in this 34-acre settlement. The site had many mudbrick buildings built on top of each other. There were spaces between them for trash (middens) and animals.

Çatalhöyük didn't show signs of careful planning. Instead, it grew as people kept building similar houses. Each house was mostly self-sufficient, meaning people did most things for themselves. There weren't special builders for houses, and the bricks used were different. There is some proof of trade, like obsidian (a type of volcanic glass) from Cappadocia, 170 km away.

This site shows little sign of strong leaders or different social classes. Yet, its complex culture and long history suggest people found other ways to live together peacefully for a long time.

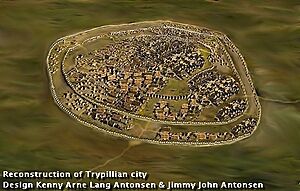

Cucuteni-Trypillia Culture: Giant Settlements

The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture (4100-3400 BC) built some of the largest settlements in southeastern Europe during the Neolithic and Eneolithic periods. These huge sites ranged from 100 to 340 hectares. Because of their size, some experts call these mega-sites proto-cities.

One Cucuteni-Trypillian site, Nebelivka in Ukraine, had about 1500 buildings. They were arranged in two circles with inner streets, dividing the settlement into 14 areas and over 140 neighborhoods. This layout might suggest some central planning. However, individual neighborhoods were quite different. Also, the site's economy and trade were similar to earlier or other settlements of its time.

Some think that social problems from so many people living together might have been solved by people moving often. This is different from developing new social and political systems in one place. So, it's not clear if these sites were truly part of an urbanization process.

How Cities Developed

The way cities grew from proto-urban sites was not always a straight path. Many proto-cities were like "early experiments" in living in high-density areas. They didn't always grow further, especially in terms of population. This suggests that the path to becoming a city was flexible and complex.

However, some proto-urban places, like Tell Brak in Northern Mesopotamia around 3000 BC, were "successful experiments." They adopted new social and political ways to handle problems. These sites showed early signs of the administrative practices seen in later Southern Mesopotamian city-states like Uruk. For example, they used seals to show ownership or control. At Tell Brak, a stamp seal with a lion on it might have shown the power of an important official. Later, Mesopotamians saw the lion as a symbol of kingship.

By the end of the fourth millennium BC, the city of Uruk in Southern Mesopotamia showed the social and political changes that had happened in proto-cities before it. Uruk was seen as the "peak of many successful experiments" in people living together in one place. It was extremely large, covering 250 hectares, twice the size of Tell Brak.

Uruk was a center of religious and political power. It had large, well-decorated houses and temples, showing that there were powerful political and religious leaders. Uruk was one of the most important early Mesopotamian cities. It has the earliest written documents (around 3300 BC) and the largest area of public buildings from that time. This makes it a key example of what archaeologists call a true city.

The rise of cities like Uruk is often linked to a "revolution" in how people lived together. This included things like people doing different jobs (division of labor) and producing extra food (agricultural surplus). These changes led to different social classes and eventually, power being held by a ruler or government. In the first cities, relationships changed from being based on kinship (family ties) to being based on where people lived or their social class.

Huge buildings, built by the state, showed political power. They might also have made ordinary people feel connected to their city and ruler through the act of construction. It's a common idea that slaves built ancient monuments. But much of the work was done by free commoners as part of their tax duties.

Some experts suggest that changes in social relations might not have been so revolutionary in the earliest cities. They think kinship might not have been replaced, but rather grew to include whole settlements and cities. Temples and palaces in Mesopotamian city-states were run like households, using family terms like "father" and "servant." Houses in villages from the Ubaid period (around 4000 BC) in Mesopotamia had the same layout as temples in Tell Brak and Uruk. So, a person in Uruk would still recognize a temple as a house, just much bigger and grander.

This means that over time, individual households might have been replaced not by a state, but by a "metaphorical household" that covered an entire city. The first cities might have even formed by accident. Ambitious family leaders trying to expand their social connections might have unintentionally grown their settlement by attracting new followers.

See also

- Aşıklı Höyük

- Bhirrana

- Çatalhöyük

- Göbekli Tepe

- Jiahu

- Lepenski Vir

- Mehrgarh

- Sesklo

- Sarazm

- Tell es-Sultan

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |