Quyllurit'i facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pilgrimage to the sanctuary of the Lord of Qoyllurit’i |

|

|---|---|

|

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage

|

|

The pilgrimage to Nevado Colque Punku

|

|

| Country | Peru |

| Reference | 567 |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2011 (6th session) |

| List | Representative |

The Quyllurit'i or Qoyllur Rit'i festival is a special religious event held every year in the Sinakara Valley in the high mountains of Cusco Region, Peru. Its name comes from the Quechua language, where quyllu rit'i means "bright white snow."

Local people in the Andes see this festival as a way to celebrate the stars. They especially honor the return of the Pleiades constellation. In Quechua, this group of stars is called Qullqa, meaning "storehouse." It is linked to the upcoming harvest and the New Year. The Pleiades stars disappear in April and come back in June.

For people in the Southern Hemisphere, the New Year starts with the Winter Solstice in June. This time is also important for Catholic celebrations. People have celebrated this period for hundreds, maybe even thousands, of years. In 2011, the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists recognized this pilgrimage and festival as an important cultural tradition.

According to the Catholic Church, the festival honors the Lord of Quyllurit'i (Quechua: Taytacha Quyllurit'i). Its story began in the late 1700s. A young local shepherd named Mariano Mayta met a boy named Manuel on the mountain Qullqipunku. Manuel helped Mariano's sheep and alpacas grow strong and healthy.

Mariano's father sent him to Cusco to buy a new shirt for Manuel. But Mariano could not find the special cloth anywhere. This type of fabric was only sold to the archbishop. When the bishop of Cusco heard this, he sent people to investigate. When they tried to catch Manuel, he turned into a bush with a picture of Christ on it. Mariano, thinking his friend was hurt, died right there. He was buried under a rock, which became a holy place. This place is now known as the Lord of Quyllurit'i, or "Lord of Star (Brilliant) Snow." A picture of Christ was painted on this rock.

The Quyllurit'i festival brings together thousands of people from nearby areas. These include groups from Paucartambo (who speak Quechua) and Quispicanchis (who speak Aymara). Both groups make an annual trip to the festival. They bring many dancers and musicians. There are four main groups of participants: ch'unchu, qulla, ukuku, and machula. More and more Peruvian city dwellers and foreign visitors also attend the festival.

The festival usually happens in late May or early June. It is timed with the full moon, one week before the Christian feast of Corpus Christi. Events include parades with holy statues and dances around the shrine of the Lord of Quyllurit'i. For the local people, a key moment happens after the Qullqa stars reappear. This is the sunrise after the full moon. Tens of thousands of people kneel to welcome the first light of the sun.

Until recently, the ukukus had a very important role for the Church. They would climb the glaciers on Qullqipunku. They would bring back crosses and blocks of ice. These were placed along the path to the shrine. People believed the ice had healing powers. However, because the glacier is melting, the ice is no longer carried down.

Contents

What are the Origins of the Quyllurit'i Festival?

There are different stories about how the Quyllurit'i festival began. Here are two main versions. One tells about its origins before the Spanish arrived. The other is the Catholic Church's story, written down by a priest between 1928 and 1946.

Pre-Columbian Origins: How Ancient People Celebrated

The Inca people followed the cycles of both the sun and the moon throughout the year. The moon's cycle was very important for planning farm work and festivals. Many celebrations were linked to raising animals, planting seeds, and harvesting crops. Important festivals like Quyllurit'i, which is very meaningful, are still celebrated during the full moon.

The Quyllurit'i festival happens after the Pleiades constellation disappears and reappears. This group of seven stars, also called the Seven Sisters, is in the Taurus constellation. It vanishes from the sky in the Southern Hemisphere for a few months. When it disappeared, Inca culture marked this with a festival for Pariacaca, the god of water and heavy rains. This time was also called qarwa mita, when corn leaves turn yellow.

About 40 days later, the constellation returns. This time, called unquy mita in Quechua, was linked to the harvest season. It meant a time of plenty for the people. Inca astronomers called the Pleiades constellation Qullqa, meaning "storehouse," in their Quechua language.

The disappearance and return of the constellation also had a deeper meaning. It showed that life can have times of trouble and confusion, but order will always return.

Catholic Church Origins: The Story of Manuel and Mariano

In the city of Cuzco in the late 1600s, the celebration of Corpus Christi was very grand. Bishop Manuel de Mollinedo y Angulo made it a huge event. There were parades through the city, with Inca nobles wearing special clothes. The bishop even had paintings made of these nobles in their ceremonial outfits.

Some historians believe that early church leaders thought Catholic rituals could replace local traditions. They studied how the Corpus Christi feast was connected to the local harvest festival, which happened during the winter solstice in early June. The Church says that events in the late 1700s, involving a sighting of Christ on Qullqipunku mountain, became part of the festival's story. The pilgrimage to the Lord of Quyllurit'i is still celebrated today.

The story tells of an Indigenous boy named Mariano Mayta. He watched his father's alpaca herd on the mountain slopes. One day, he met a mestizo boy named Manuel in the snowy areas of the glacier. They became good friends. Manuel often gave Mariano food. When Mariano didn't come home for meals, his father went to find him. He was surprised to see that his herd had grown much larger.

As a reward, Mariano's father sent him to Cusco to buy new clothes. Mariano asked to buy some for Manuel too, as Manuel always wore the same outfit. His father agreed. Mariano asked Manuel for a piece of his clothing so he could buy the same kind of fabric in Cusco.

In Cusco, Mariano was told that this fine cloth was only for the city's bishop. Mariano went to see the bishop, who was surprised by the request. The bishop ordered an investigation of Manuel. The priest from Oncogate (Quispicanchi), a village near the mountain, led the search. On June 12, 1783, the group went up Qullqipunku with Mariano. They found Manuel dressed in white and shining with a bright light. Blinded, they went back and returned with a bigger group.

On their second try, they reached the boy. But when they touched him, he turned into a tayanka bush (Baccharis odorata) with a crucified Christ hanging from it. Mariano, thinking his friend had been harmed, died right there. He was buried under the rock where Manuel had last appeared.

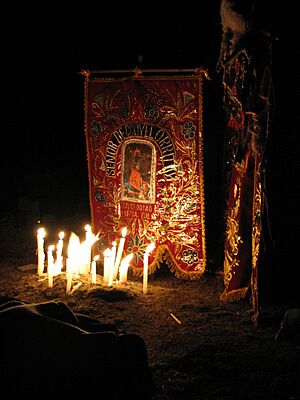

The tayanka tree was sent to Spain, as King Charles III had asked for it. It was never returned, and the local Indigenous people protested. The local priest ordered a copy to be made. This copy became known as Lord of Tayankani (Spanish: Señor de Tayankani). Mariano's burial spot attracted many Indigenous followers. They lit candles before the rock. Religious leaders then ordered a picture of Christ crucified to be painted on the rock. This image became known as Lord of Quyllurit'i (Spanish: Señor de Quyllurit'i). In Quechua, quyllur means star and Rit'i means snow. So, the name means Lord of Star Snow.

Who are the Pilgrims?

More than 10,000 pilgrims visit the Quyllurit'i festival each year. Most are Indigenous people from rural communities nearby. They come from two main groups:

- The Quechua-speaking Paucartambo people. They are farmers from areas northwest of the shrine, in provinces like Cusco, Calca, Paucartambo, and Urubamba.

- The Aymara-speaking Quispicanchis people. They live southeast of the shrine, in provinces like Acomayo, Canas, Canchis, and Quispicanchi. These people are mostly herders, raising alpacas and llamas.

Farmers from both groups make an annual trip to the Quyllurit'i festival. Each community brings a small image of Christ to the holy place. Together, these groups include many dancers and musicians. They dress in four main styles:

- Ch'unchu: These dancers wear feathered headdresses and carry a wooden staff. They represent the Indigenous people from the Amazon Rainforest to the north. The most common type is wayri ch'unchu, making up about 70% of all dancers at Quyllurit'i.

- Qhapaq Qulla: These dancers wear a knitted mask called a "waq'ullu," a hat, a woven sling, and a llama skin. They represent the Aymara people from the Altiplano (high plains) to the south. Qulla is seen as a mixed-culture dance, while ch'unchu is considered purely Indigenous.

- Ukuku: Dressed in a dark coat and a woolen mask, the ukukus (meaning spectacled bear) act as tricksters. They speak in high-pitched voices and play jokes. However, they also have the serious job of keeping order among the thousands of pilgrims. Some ukukus used to climb the glacier and bring back blocks of ice. This melted water was believed to be medicinal and used as holy water. In Quechua stories, ukukus are the children of a woman and a bear. They are feared for their strength but can become good people by defeating evil spirits.

- Machula: These dancers wear a mask, a humpback, and a long coat, carrying a walking stick. They represent the ñawpa machus, the mythical first people of the Andes. Like the ukukus, they play a dual role, being both funny and helping to keep order.

Quyllur Rit'i also attracts visitors from outside these traditional groups. Since the 1970s, more middle-class Peruvians have joined the pilgrimage. There has also been a fast increase in visitors from North America and Europe. This has led to worries that the festival might become too focused on money. The pilgrimage and festival were added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists in 2011.

What Happens at the Festival?

Thousands of Indigenous people attend the festival. Some travel from as far away as Bolivia. The Christian part of the celebration is organized by the Brotherhood of the Lord of Quyllurit'i (Spanish: Hermandad del Señor de Quyllurit'i). This group also helps keep things orderly during the festival.

Preparations begin on the feast of the Ascension. On this day, the statue of the Lord of Quyllurit'i is carried in a procession. It travels 8 kilometers from its chapel at Mawallani to its holy place at Sinaqara.

On the first Wednesday after Pentecost, another procession takes a statue of Our Lady of Fatima. It goes from the Sinaqara sanctuary to a grotto (a small cave) uphill. Most pilgrims arrive by Trinity Sunday. On this day, the Blessed Sacrament is carried in a procession around the sanctuary.

The next day, the Lord of Qoyllur Rit'i is carried in a procession to the Virgin's grotto and back. Pilgrims call this the "greeting" between the Lord and Mary. This connects to the old Inca festivals of Pariacaca and Oncoy mita. On the night of this second day, dance groups take turns performing inside the shrine.

At dawn on the third day, ukukus groups climb the glaciers on Qullqipunku. They go to get crosses placed on top. Some ukukus used to spend the night on the glacier to fight off bad spirits. They also used to cut and bring back blocks of ice. This ice was believed to have sacred healing powers. The ukukus were thought to be the only ones who could deal with condenados, which are cursed souls said to live in the snow.

Old stories say that ukukus from different groups used to have ritual battles on the glaciers. However, the Catholic Church banned this practice. After a special mass later that day, most pilgrims leave the sanctuary. One group carries the Lord of Quyllurit'i in a procession to Tayankani before taking it back to Mawallani.

The festival happens before the official feast of Corpus Christi. Corpus Christi is held on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday. However, the two festivals are very closely linked.

See also

In Spanish: Quyllurit'i para niños

In Spanish: Quyllurit'i para niños

- Religion in Peru

- Syncretism

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |