Recorder facts for kids

Various recorders (second from the bottom disassembled into its three parts)

|

|

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | See § Other languages |

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 421.221.12 (Flute with internal duct and finger holes) |

| Playing range | |

| Soprano recorder: C5–D7(G7) | |

| Related instruments | |

|

|

| Musicians | |

| Recorder players | |

The recorder is a musical instrument that is a type of flute. It looks like a tube that is wider at one end. A recorder player blows into the wider end to make sounds.

In Europe, people started playing the recorder a long time ago, during medieval times. Musicians often used it to sound like bird songs. Famous composers like Purcell, Bach, Telemann, and Vivaldi all wrote music for the recorder.

By the 1900s, fewer people played the recorder. Other instruments, like the flute, became more popular. These instruments were often louder and better for playing complex music.

However, in the 1900s, more people began to learn the recorder again. One reason was a new interest in playing old music on the instruments it was written for. Another reason is that the recorder is a great instrument for children to learn about music.

Contents

A Look Back: The Recorder's Journey

Whistles are very old instruments. Some whistles found by archaeologists are from the Iron Age. A recorder is a special kind of whistle. It has seven holes for your fingers and one for your thumb. The first recorders were made around the 1500s. Parts of these old recorders have been found in places like Germany, the Netherlands, and Greece.

Many people in Europe played the recorder in the 1500s and 1600s. King Henry VIII of England owned 76 recorders! William Shakespeare mentioned recorders in his play Hamlet. John Milton also wrote about them in his poem Paradise Lost. Recorders from this time are called Renaissance recorders.

In the 1600s, recorder makers found new ways to improve the sound. They also wanted the instruments to play more challenging music. Recorders from this period are called Baroque recorders. They were thinner than Renaissance recorders. They were also made in several parts that fit together. You can see one recorder in three parts in the picture at the top of this page.

After the mid-1700s, people started to prefer the flute and clarinet. Flutes could play a wider range of notes. They were also better for music with many chromatic notes (notes that are half steps apart).

The Recorder Today

In the 1900s, people wanted to play old music using the instruments from that time. In England, Arnold Dolmetsch was famous for this. Other musicians also started playing the recorder in serious concerts. These included Frans Brüggen and David Munrow.

Today, new music is still being written for the recorder. Composers like Paul Hindemith and Benjamin Britten have written pieces for it.

The recorder is sometimes used in popular music too. The Beatles played the recorder in their song Fool on the Hill. The Rolling Stones used one in Ruby Tuesday (song).

Plastic recorders were invented in the 20th century. They are usually cheap and easy for beginners. Many elementary schools use plastic recorders to teach children about music.

The top part of the recorder, called the head joint, can also be used on its own. It works like a whistle and is sometimes used as a toy. You can make rhythms and sound effects with it. Some teachers use it to help children get used to the instrument.

Different Kinds of Recorders

Recorders come in many different sizes. The lowest note a recorder can play is usually C or F. This is the note you hear when all the holes are covered.

The soprano recorder is the size most often played in schools. It is also called a Descant recorder. Its lowest note is C. Some recorders are smaller than the soprano, but they are not as common.

The alto recorder is bigger than the soprano. Its lowest note is F. Other main sizes include the tenor recorder (lowest note C) and the bass recorder (lowest note F). There are even larger recorders, but they are rare. Smaller recorders like the Sopranino and Garklein also exist.

Playing Together: Recorder Groups

The recorder is a very social instrument. Many people enjoy playing it in small or large groups. These groups often play music written for several different sizes of recorders.

Usually, there are separate parts for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass recorders. This allows the group to play a wide range of notes, from high to low. Some music is written for two recorders (a duet), three (a trio), or four (a quartet). These groups are called ensembles, which means "together" in French. Some people even play in recorder orchestras with many players and different instrument sizes!

How to Play the Recorder

The way you play the recorder has stayed mostly the same over its 700-year history. This is true even for recorders of different sizes and from different time periods.

Holding the Recorder

When you play, you hold the recorder with both hands. Your fingers cover the holes or press keys. Four fingers are on the lower hand, and three fingers and your thumb are on the upper hand. Usually, your right hand is the lower hand, and your left hand is the upper hand.

Your lips gently hold the mouthpiece, called the beak. The thumb of your lower hand also helps support the instrument. Other fingers and your upper thumb help too, depending on the note you are playing.

Recorders are usually held at an angle, somewhere between straight up and straight out. The angle depends on the recorder's size and how you like to hold it.

Using Your Fingers

| Fingers | Holes |

|---|---|

|

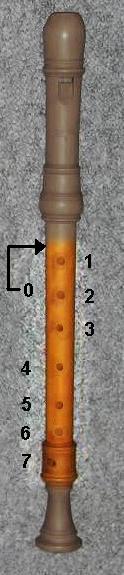

You make different notes on the recorder by covering the holes while blowing. The holes on the front are numbered 1 through 7, starting from the top. The thumbhole on the back is called hole 0.

To play higher notes, you usually uncover the holes one by one, starting from the bottom. For example, you might uncover hole 7, then holes 7 and 6, and so on. But sometimes, you need to cover or uncover holes only halfway. This is an important part of playing the recorder well.

Tricky Fingerings: Forked Fingerings

A "forked fingering" is when you have an open hole, but there are covered holes below it. For example, if you cover holes 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6, but leave hole 4 open, that's a forked fingering. This is because hole 4 is open, but holes 5 and 6 below it are covered.

Forked fingerings help you make small changes to the note's pitch. They can also create slightly different sounds. Sometimes, they are used as "alternate fingerings" if a note sounds a bit off.

Half-Covering Holes

Partially covering holes is a key part of playing the recorder. This is sometimes called "leaking," "shading," or "half-holing." For the thumbhole, it's called "pinching."

The thumbhole helps you play higher notes. When you half-cover it, the air inside the recorder vibrates differently, allowing you to play notes in a higher octave. You have to adjust your thumb carefully to make these notes sound clear and in tune.

You can half-cover a hole by sliding your finger off it, or by bending your finger slightly. Half-opening a covered hole usually makes the note higher. Half-closing an open hole usually makes the note lower.

Holes 6 and 7

On most modern "baroque" recorders, the bottom two fingers of your lower hand cover two small holes each. Older recorders had single holes. By covering one or both of these smaller holes, you can play notes that are a half-step or a minor third above the lowest note. On older recorders, you had to half-cover the single hole or cover the end of the recorder to play these notes.

Covering the Bell

You can also cover the open end of the recorder (called the "bell") to make extra notes or effects. Since both hands are usually busy, you often do this by touching the end of the recorder to your leg or knee. You might bend your body or lift your knee to do this.

Using Your Breath

The speed of the air you blow into the recorder affects how high or loud the note is. Faster air generally makes a higher note. So, blowing harder makes a note sound sharper, and blowing gently makes it sound flatter.

Breathing for the Recorder

Playing the recorder doesn't need a lot of air pressure, unlike instruments like trumpets. Recorder players need to blow long, steady streams of air very gently. The focus is on controlling the air release, not on pushing hard from your diaphragm.

Tongue, Mouth, and Throat

Using your tongue to start and stop the air is called "articulation." Your tongue helps control how a note begins (the "attack") and how long it lasts (smooth or short).

The shape of your mouth and throat, like when you say different vowels, also affects the sound. This shape changes how fast and smoothly the air goes into the recorder. The way you shape your mouth and throat is also linked to the sounds you make with your tongue.

Basic Fingerings

| Recorder fingerings (English): Lowest note through the nominal range of 2 octaves and a sixth | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note | First octave | Second octave | Third octave | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tuned in F |

Tuned in C |

Hole 0 |

Hole 1 |

Hole 2 |

Hole 3 |

Hole 4 |

Hole 5 |

Hole 6 |

Hole 7 |

Hole 0 |

Hole 1 |

Hole 2 |

Hole 3 |

Hole 4 |

Hole 5 |

Hole 6 |

Hole 7 |

Hole 0 |

Hole 1 |

Hole 2 |

Hole 3 |

Hole 4 |

Hole 5 |

Hole 6 |

Hole 7 |

End hole 8 |

||||||||

| F | C | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| F♯/G♭ | C♯/D♭ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ◐ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| G | D | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ||||||||

| G♯/A♭ | D♯/E♭ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ◐ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ◐ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| A | E | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ||||||||

| A♯/B♭ | F | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ◐ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ||||||||

| B | F♯/G♭ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| C | G | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| C♯/D♭ | G♯/A♭ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ◐ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| D | A | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| D♯/E♭ | A♯/B♭ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | |||||||||||||||||

| E | B | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | |||||||||||||||||

● means to cover the hole. ○ means to uncover the hole. ◐ means half-cover.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |