Redgrave and Lopham Fens facts for kids

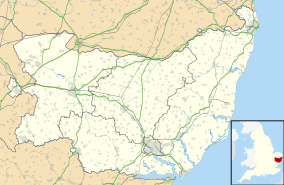

Redgrave and Lopham Fens is a special natural area in England. It covers about 127 hectares (that's like 314 football fields!). This amazing place is located between the villages of Thelnetham in Suffolk and Diss in Norfolk.

It's not just any patch of land; it's a very important Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). This means it's protected because of its rare plants, animals, or geology. It's also a National Nature Reserve and a Ramsar wetland, which are international protections for important wet habitats. The Suffolk Wildlife Trust looks after this special place.

Redgrave and Lopham Fens is the biggest area of its kind in England. It has many different types of fen (a type of wetland), including areas with tall saw-sedge plants. You can also find open water, heathland, bushes, and trees here. It's super important because it's one of only three places in the UK where the rare fen raft spider (Dolomedes plantarius) lives!

Contents

Amazing Wildlife at the Fens

The different types of habitats at Redgrave and Lopham Fens create a perfect home for many plants and animals. This area is a valley mire, which means it's a wetland that formed in a river valley. This creates different zones of plants, from dry woodlands to wet grasslands.

You'll see purple moor-grass in the grasslands. As you get wetter, you'll find areas of reeds and sedges. A special plant here is the saw sedge (Cladium mariscus), which is quite unique.

Some parts of the fen have sandy ridges with heath plants. If these areas aren't managed, they can get taken over by sallow bushes and become scrubland. To keep the fen diverse, some areas are allowed to become scrubland, while others are kept open.

Meet the Animals

This special mix of habitats supports a huge variety of creatures. The fen is especially famous for its many different invertebrate species (animals without backbones).

- Spiders: The most famous resident is the fen raft spider (Dolomedes plantarius). This large, rare spider is a national treasure!

- Insects: Scientists have found 19 types of dragonfly and 27 types of butterfly here. Imagine how many colorful insects you could spot!

- Mammals: There are 26 kinds of mammals, including playful otters, tiny pipistrelle bats, and even Chinese water deer.

- Amphibians and Reptiles: Four types of amphibians (like frogs and newts) and four types of reptiles (like snakes and lizards) also call the fen home.

- Birds: In 2006, 96 different bird species were seen visiting the fen. It's a birdwatcher's paradise!

Looking After the Fens

To keep Redgrave and Lopham Fens healthy and full of diverse species, it needs constant care. The Suffolk Wildlife Trust has a Site Manager and an Assistant Warden who work hard to look after the fen. They also get a lot of help from volunteers!

This important work includes:

- Mowing rushes and harvesting sedges.

- Clearing away unwanted bushes (scrub clearance).

- Coppicing (cutting trees back to the stump to encourage new growth).

- Building fences.

The fen also uses a clever method called grazing to help manage the land.

Grazing Animals as Helpers

Animals like sheep, cattle, and ponies are part of the management plan. They eat the plants, which helps keep the fen healthy and stops it from becoming overgrown. This has made the fen much better, creating a mix of different plant types and stopping bushes from spreading.

- Sheep and Cattle: Hebridean sheep (owned by the trust) and beef cattle from local farms graze on the drier parts of the fen. They help keep the scrub and heath areas open.

- Konik Ponies: In 1995, a herd of Polish Konik ponies was brought in. These ponies are super tough and can graze in very wet conditions. They've been so successful that other nature reserves in the UK now use them, even on the Broads! The cattle and Koniks usually graze from April to December, avoiding the coldest and wettest months.

Protecting the Fen Raft Spider

Redgrave and Lopham Fens was the first place in the UK where the fen raft spider was found in 1956. To help them, new pools were dug. However, in the 1980s, water was being taken from a borehole nearby, and there were droughts. This meant the spider population shrank to only two small areas. During this tough time, people had to water the pools to keep the spiders alive.

In 1999, the borehole was closed, and everyone hoped water levels would return to normal. But a study in 2006 showed that the spider population was still small. Experts suggested making the pools deeper, creating more new pools, and managing the water more carefully to help these special spiders thrive.

Visiting Redgrave and Lopham Fens

You can visit the reserve all year round! It has an Education Centre that hosts fun family activity days, school trips, and courses for adults. There's also a picnic area and toilets.

The reserve has three walking trails: 2 km, 3 km, and 4.5 km long. Some parts of the trails are even suitable for wheelchairs, so everyone can enjoy the beautiful nature.

A Look Back in Time: History of the Fens

How the Fens Were Used Long Ago

Redgrave and Lopham Fens sits at the start of the Waveney and Little Ouse rivers. For hundreds of years, local people used the fen for its natural resources. This activity actually helped create and maintain the different habitats we see today!

- Peat Cutting: People cut peat (a type of soil made from decayed plants) for fuel. This created open pools surrounded by reedbeds and pathways that became rich fen meadows.

- Harvesting Plants: Sedge and reed were cut for thatching roofs. Furze (a spiky bush) and other plants were gathered for animal bedding and firewood.

- Grazing: Cattle and other farm animals grazed on the meadows and heathland. This stopped unwanted plants from growing too much and kept the fen diverse.

However, as farming became more industrial and people started using fossil fuels, the traditional ways of managing the fen slowly stopped.

In 1954, Redgrave and Lopham Fens was officially recognized as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). This was because of the rare fen raft spider and the amazing variety of its fenland.

The Fen's Challenges (1959-1991)

In 1959, a borehole (a deep hole drilled into the ground) was made at the fen to get drinking water for local people. This borehole could take out a huge amount of water every day! This meant less water reached the fen's natural springs, and the water levels started to drop.

By the early 1960s, the fen's water system changed a lot. Instead of having water all year, it would be dry in summer and flooded in winter. Overall, the fen was losing water and starting to dry out.

Because of the water loss and lack of traditional management, the fen started to get damaged. Bushes began to take over large areas. In 1961, the Suffolk Wildlife Trust took control of the site. But they didn't have enough money or resources to fix the big problems, so the fen continued to decline.

A New Beginning (1991-Present)

In the early 1990s, more people realized how important Redgrave and Lopham Fens was. It was named a Ramsar site in 1991 and a National Nature Reserve in 1993. Around this time, the Environment Agency studied the damage and figured out how to restore the fen.

This led to a huge and internationally recognized restoration project! It cost about £3.4 million (that's a lot of money!).

Bringing the Fen Back to Life

The big restoration project had three main goals: moving the borehole, restoring the river, and restoring the fen itself. The European Commission helped pay for half of the cost through the LIFE Fund.

Moving the Borehole

To bring the fen's natural water levels back, the borehole that was taking water away needed to be moved. A long search found a new site 3 km southeast of the reserve. Building the new borehole cost £1.2 million. This was the first time a public water borehole was moved just to help the environment!

The old borehole was shut down in July 1999. Within just one month, water levels in the fen started to rise a lot. By 2002, the water levels were back to normal, just as predicted. This return to natural water has solved many problems. Now, the peat soils and reed beds have enough water all year. Many old peat cuttings have also filled with water, creating small pools with plants growing in them.

Restoring the River

The River Waveney flows through the reserve and can affect the fen's health. The restoration project aimed to raise the river's water level and bring its natural ecology back.

- Sluice Gates: Two adjustable sluice gates were added to the river. These gates allow direct control of water levels, protecting the fen from floods or droughts.

- River Banks: The river banks were reshaped to create more habitats for wildlife, like shallow shelves that water voles love. The soil removed from the banks was used to build flood defense levees (raised banks) along the river.

Restoring the Fen Itself

The final part of the project was to bring back the most important fen plant communities. This involved clearing away bushes and trees and removing damaged peat.

- Clearing Land: About 80 hectares of wood and scrub were cleared. This opened up the land so the fen habitat could return.

- Peat Stripping: Over the years, large areas of peat had been damaged because of the lack of water. To fix this, the decision was made to strip off the damaged peat until healthy peat was reached. By 2002, about 250,000 tonnes of peat had been removed. This created many large pools surrounded by reed beds. Over time, new peat will start to form again from the annual growth and decay of fen plants.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |