Rime dictionary facts for kids

A rime dictionary (also called a rhyme dictionary or rime book) is a special type of dictionary from China. Unlike regular dictionaries that group words by their parts, rime dictionaries group Chinese characters by how they sound, focusing on their tone and rhyme.

The most important rime dictionary is the Qieyun, created in 601 AD. It helped set the standard for how Chinese characters should be pronounced when reading old texts and writing poems. This book became very popular during the Tang dynasty. Over time, it was updated and expanded many times. The most famous update is the Guangyun, which came out in 1007–1008 AD.

These dictionaries explain how to say characters using a method called fanqie. This method uses two other characters to show the sound of a character. One character shows the beginning sound of the syllable, and the other shows the rest of the syllable. Later, special rime tables were made. These tables organized the sounds from these dictionaries in a much clearer way. The sound system found in these books is known as Middle Chinese. It helps experts understand how ancient Chinese sounded.

Some experts use the French spelling rime (pronounced "reem") for the sound groups in these dictionaries. This helps tell them apart from the idea of poetic rhyme.

Contents

How Chinese Pronunciation Guides Developed

Chinese scholars created these dictionaries to make sure everyone read classic texts correctly. They also helped poets follow the right rhyming rules for their poems. The very first rime dictionary was the Shenglei (meaning 'sound types'). It was written by Li Deng during the Three Kingdoms period and had over 11,000 characters. Sadly, this book is lost today, and we only know about it from other old writings.

Over time, different schools of thought in China created their own dictionaries. These often had different ideas about how words should be pronounced. The most respected ways of speaking came from the northern capital, Luoyang, and the southern capital, Jinling (which is now Nanjing).

In 601 AD, a scholar named Lù Fǎyán published his Qieyun. He tried to combine the best parts of five earlier dictionaries into one. Lu Fayan wrote that he planned the book 20 years earlier with other scholars. But he finished putting it together by himself after he stopped working for the government.

The Qieyun quickly became the official way to pronounce words during the Tang dynasty. Because it was so popular, the older dictionaries it was based on were no longer used and disappeared. Many updated versions of the Qieyun were made. Here are some of the most important ones:

| Date | Compiler (Who Made It) | Title |

|---|---|---|

| 601 | Lù Fǎyán 陸法言 | Qièyùn 切韻 |

| 677 | Zhǎngsūn Nèyán 長孫訥言 | Qièyùn 切韻 |

| 706 | Wáng Rénxū 王仁煦 | Kānmiù bǔquē Qièyùn 刊謬補缺切韻 (Corrected and Supplemented Qieyun) |

| 720 | Sūn Miǎn 孫愐 | Tángyùn 唐韻 |

| 751 | Sūn Miǎn 孫愐 | Tángyùn 唐韻 (second edition) |

| 763–84 | Lǐ Zhōu 李舟 | Qièyùn 切韻 |

In 1008 AD, during the Song dynasty, the emperor asked a group of scholars to create a bigger, updated version. This became the Guangyun. Later, the Jiyun (1037 AD) was an even larger update of the Guangyun. Lu Fayan's first Qieyun mainly helped with pronunciation. But later versions added more detailed meanings, making them useful as full dictionaries.

For a long time, the Guangyun and Jiyun were the oldest complete rime dictionaries known. So, most studies of the Qieyun were actually based on the Guangyun. However, in the early 1900s, parts of older Qieyun versions were found among the Dunhuang manuscripts and in other places like Turfan and Beijing.

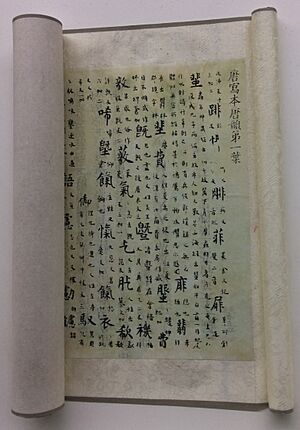

When the Qieyun became the national standard in the Tang dynasty, many copyists made new versions. Copies of Wáng Rénxū's edition, made by a famous calligrapher named Wú Cǎiluán in the early 800s, were especially valued. One of these copies ended up in the palace library of Emperor Huizong of Song. It stayed there until 1926. After World War II, it was found by scholars in a book market in Beijing. This almost complete copy has helped Chinese linguists like Dong Tonghe and Li Rong learn a lot about the Qieyun.

How Rime Dictionaries Are Organized

The Qieyun and the dictionaries that followed it all had a similar way of organizing words.

- First, characters were sorted into four tones. The 'level tone' (平聲; píngshēng) had so many characters that it filled two volumes. The other three tones each filled one volume.

- The last tone, called the 'entering tone' (入聲; rùshēng), included words ending in sounds like -p, -t, or -k. These sounds often match words ending in -m, -n, and -ng in the other tones. In many southern Chinese languages today, these ending sounds are still there. But in most northern Chinese languages, including standard Mandarin, they have disappeared.

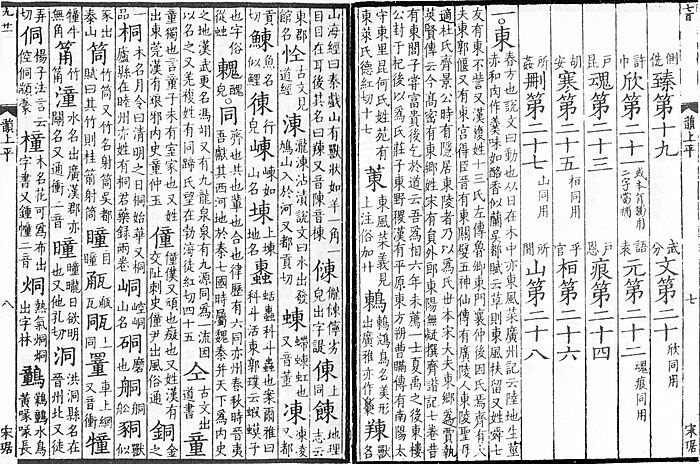

Each tone was then divided into groups based on their rhyme (韻 yùn). These groups were usually named after the first character in that group, called the yùnmù (韻目 'rhyme eye'). Lu Fayan's Qieyun had 193 rhyme groups. Later versions, like Li Zhou's, expanded this to 206.

Inside each rhyme group, characters were further divided into homophone groups. These are groups of characters that sound exactly the same. A small circle called a niǔ (紐 'button') marked the start of each homophone group.

For every character, the dictionary gave a short explanation of its meaning. For the first character in a homophone group, it also explained its pronunciation using a fanqie formula. This formula used two other characters: one for the beginning sound (聲母 shēngmǔ) and one for the ending sound (韻母 yùnmǔ). For example, to say 東 ('east'), the dictionary might use the characters 德 and 紅. This means you combine the beginning sound of 德 with the ending sound of 紅 to get the pronunciation of 東.

After the fanqie formula, the dictionary would show the character 反 (in Qieyun) or 切 (in Guangyun). Then, it would tell you how many other characters had the exact same pronunciation. For instance, if it said 十七, it meant there were 17 characters, including the first one, that sounded alike.

The order of the rhyme groups within each volume didn't seem to follow a strict rule. However, similar groups were often placed together. Also, groups that matched across different tones were usually in the same order. If two rhyme groups were very similar, they often used example words that started with the same sound. The Guangyun's table of contents marked nearby rhyme groups as tóngyòng (同用). This meant they could rhyme with each other in poetry.

Understanding the Sounds of Middle Chinese

Experts have studied these rime dictionaries very closely. They are important clues for understanding the sounds of medieval Chinese, a language system called Middle Chinese. Since the Qieyun itself was thought to be lost until the mid-1900s, most of this work was based on the Guangyun.

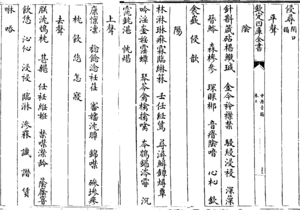

These dictionaries list all the syllables and their pronunciations. But they don't explain the full sound system of the language. The first attempts to do this were the rime tables. The oldest of these tables are from the Song dynasty, but the idea might go back to the late Tang dynasty. These tables broke down the syllables from the rime books into different parts, like starting sounds, ending sounds, and other features. The starting sounds were even analyzed by where and how they were made in the mouth. This suggests that ancient Chinese scholars might have been inspired by Indian linguistics, which was very advanced at the time.

However, the rime tables were created centuries after the Qieyun. By then, some of the original sound differences in the Qieyun might have been unclear. Some scholars, like Edwin Pulleyblank, believe the rime tables describe a later stage of Middle Chinese, different from the earlier stage in the rime dictionaries.

Reconstructing Ancient Chinese Sounds

A linguist named Bernard Karlgren tried to figure out the actual sounds of the categories in the Guangyun. He compared them with other types of evidence. For example, he looked at Sino-Xenic pronunciations. These are Chinese words borrowed into Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese long ago. He also studied modern varieties of Chinese. By comparing all these, Karlgren believed he could reconstruct the way people spoke in the capital city of Chang'an during the Sui and Tang dynasties.

Later experts have improved on Karlgren's work. Here are the starting sounds (initials) from the Qieyun system, with their traditional names and approximate sounds:

| Stops and Affricates | Nasals | Fricatives | Approximants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain | With breath | Voiced | Plain | Voiced | |||

| Lip Sounds | 幫 [p] | 滂 [pʰ] | 並 [b] | 明 [m] | |||

| Dental Sounds | 端 [t] | 透 [tʰ] | 定 [d] | 泥 [n] | |||

| Retroflex Stops | 知 [ʈ] | 徹 [ʈʰ] | 澄 [ɖ] | 娘 [ɳ] | |||

| Side Sound | 來 [l] | ||||||

| Dental Hissing Sounds | 精 [ts] | 清 [tsʰ] | 從 [dz] | 心 [s] | 邪 [z] | ||

| Retroflex Hissing Sounds | 莊 [tʂ] | 初 [tʂʰ] | 崇 [dʐ] | 生 [ʂ] | 俟 [ʐ] | ||

| Palatal Sounds | 章 [tɕ] | 昌 [tɕʰ] | 禪 [dʑ] | 日 [ɲ] | 書 [ɕ] | 船 [ʑ] | 以 [j] |

| Back-of-Mouth Sounds | 見 [k] | 溪 [kʰ] | 群 [ɡ] | 疑 [ŋ] | |||

| Throat Sounds | 影 [ʔ] | 曉 [x] | 匣/云 [ɣ] | ||||

The sounds in modern Chinese languages often come from these Qieyun initial sounds. For example, some Chinese dialects like Wu Chinese still keep the difference between voiced and unvoiced sounds. But in most other dialects, this difference is gone. Also, new sounds have appeared. For instance, sounds made with lips and teeth (labiodental) have split off from just lip sounds (labial). This change was already seen in the Song dynasty rime tables.

It's been harder to figure out the exact phonetic values for the ending sounds (finals). Many of the differences in the Qieyun have been lost over time. Most scholars agree that some finals had a "y" sound (like in "yes") in the middle. A "w" sound (like in "water") in the middle is also widely accepted. The ending sounds are believed to be similar to those in many modern Chinese languages: "y" and "w" glides, "m", "n", and "ng" nasal sounds, and "p", "t", and "k" stop sounds.

The Chinese linguist Li Rong studied the early Qieyun copy found in 1947. He showed that the later, expanded dictionaries kept the sound structure of the Qieyun mostly the same. The main difference was that two initial sounds, /dʐ/ and /ʐ/, merged into one. For example, even though the Guangyun had more rhyme groups than the Qieyun, the changes were mostly about splitting groups based on whether they had a "w" sound in the middle or not.

However, the introduction to the recovered Qieyun suggests it was a mix of northern and southern pronunciations. Most linguists now think that no single dialect at the time had all the sound differences recorded in the Qieyun. But each difference probably existed somewhere. For instance, the Qieyun separated three rhyme groups (支, 脂, and 之) that all sound like zhī in modern Chinese. Even though these groups have merged in all modern Chinese languages, the Qieyun still gives us important information about how Chinese sounded in earlier times.

Pingshui Rhyme Categories for Poetry

From early in the Tang dynasty, students taking the imperial examination had to write poems and rhymed essays. They had to follow the rhyme rules of the Qieyun. But poets found the many rules of the Qieyun too strict. So, scholars like Xu Jingzong suggested simpler rhyming rules.

The Píngshuǐ (平水) system, which had 106 rhyme groups, eventually became the required system for the imperial exams. This system was first put into order during the Jin dynasty. It became the standard for official rhyme books and was used to organize other reference books, like the Peiwen Yunfu.

The Pingshui rhyme groups are mostly the same as the tóngyòng (rhyming together) groups from the Guangyun, with a few small changes.

| 平 Level | 上 Rising | 去 Departing | 入 Entering |

|---|---|---|---|

| 東 dōng | 董 dǒng | 送 sòng | 屋 wū |

| 冬 dōng | 腫 zhǒng | 宋 sòng | 沃 wò |

| 江 jiāng | 講 jiǎng | 絳 jiàng | 覺 jué |

| 支 zhī | 紙 zhǐ | 寘 zhì | |

| 微 wēi | 尾 wěi | 未 wèi | |

| 魚 yú | 語 yǔ | 御 yù | |

| 虞 yú | 麌 yǔ | 遇 yù | |

| 齊 qí | 薺 jì | 霽 jì | |

| 泰 tài | |||

| 佳 jiā | 蟹 xiè | 卦 guà | |

| 灰 huī | 賄 huì | 隊 duì | |

| 真 zhēn | 軫 zhěn | 震 zhèn | 質 zhì |

| 文 wén | 吻 wěn | 問 wèn | 物 wù |

| 元 yuán | 阮 ruǎn | 願 yuàn | 月 yuè |

| 寒 hán | 旱 hàn | 翰 hàn | 曷 hé |

| 刪 shān | 潸 shān | 諫 jiàn | 鎋 xiá |

| 先 xiān | 銑 xiǎn | 霰 xiàn | 屑 xiè |

| 蕭 xiāo | 篠 xiǎo | 嘯 xiào | |

| 肴 yáo | 巧 qiǎo | 效 xiào | |

| 豪 háo | 晧 hào | 號 hào | |

| 歌 gē | 哿 gě | 箇 gè | |

| 麻 má | 馬 mǎ | 禡 mà | |

| 陽 yáng | 養 yǎng | 漾 yàng | 藥 yào |

| 庚 gēng | 梗 gěng | 映 yìng | 陌 mò |

| 青 qīng | 迥 jiǒng | 徑 jìng | 錫 xī |

| 蒸 zhēng | 職 zhí | ||

| 尤 yóu | 有 yǒu | 宥 yòu | |

| 侵 qīn | 寑 qǐn | 沁 qìn | 緝 qì |

| 覃 tán | 感 gǎn | 勘 kàn | 合 hé |

| 鹽 yán | 琰 yǎn | 豔 yàn | 葉 yè |

| 咸 xián | 豏 xiàn | 陷 xiàn | 洽 qià |

Yan Zhengqing's Yunhai jingyuan (around 780 AD) was the first rime dictionary that listed words with more than one syllable, not just single characters. Even though this book is no longer around, it became the model for many other encyclopedic dictionaries. These later dictionaries organized literary words and phrases using the Pingshui rhyme groups. The most famous of these is the Peiwen Yunfu (1711 AD).

Dictionaries for Everyday Language

When foreign rulers took over northern China between the 900s and 1300s, many old traditions changed. New types of everyday literature appeared, like qu and sanqu poems. This also led to the creation of the Zhongyuan Yinyun by Zhōu Déqīng in 1324. This book was a guide for rhyming in qu poetry.

The Zhongyuan Yinyun was very different from the old rime tables. It grouped words into 19 rhyme classes, each named after two example characters. These rhyme classes combined rhymes from different tones. The dictionary shows how northern Chinese was spoken at that time. For example, the old 'even tone' was split into upper and lower tones. Also, the ending stop sounds from Middle Chinese were gone. Words that used to have these sounds were now put into other tone groups.

An early Ming dynasty dictionary called Yùnluè yìtōng by Lan Mao was based on the Zhongyuan Yinyun. But it arranged the homophone groups in a set order of starting sounds. These starting sounds were listed in a special poem to help people remember them.

Later, a rime dictionary from the late 1500s described the Fuzhou dialect. This work is still around today in the Qi Lin Bayin. This book listed all the ending sounds of the dialect, showing differences based on middle sounds and rhymes. It also uniquely classified each homophone group by its ending sound, starting sound, and tone. Both the ending and starting sounds were listed in special poems.

Tangut Language Dictionaries

Tangut was the language of the Western Xia state (1038–1227), which was located in what is now Gansu province. The language died out about 400 years before many old Tangut documents were found in the early 1900s.

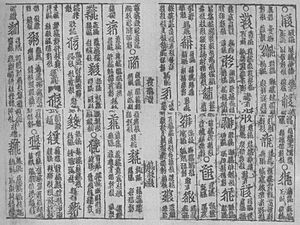

One of the important sources used to figure out the Tangut language is the Sea of Characters (Chinese: 文海; pinyin: Wénhǎi). This is a rime dictionary written completely in Tangut. It has the same structure as the Chinese dictionaries. The dictionary has one volume for the Tangut level tone and one for the rising tone. There's also a third volume for "mixed category" characters, but what that means isn't fully clear.

Just like the Chinese dictionaries, each volume is divided into rhymes. Then, these are split into groups of characters that sound the same, marked by a small circle. The pronunciation of the first Tangut character in each homophone group is given using a fanqie formula, but with Tangut characters. Experts like Mikhail Sofronov used this fanqie method to understand the system of Tangut starting and ending sounds.

Images for kids

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |