Robert Gray's Columbia River expedition facts for kids

|

|

| Date | May 11 to 20, 1792 |

|---|---|

| Location | Columbia River North America |

| Participants | Gray, crew of Columbia Rediviva |

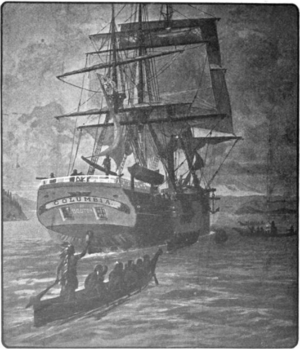

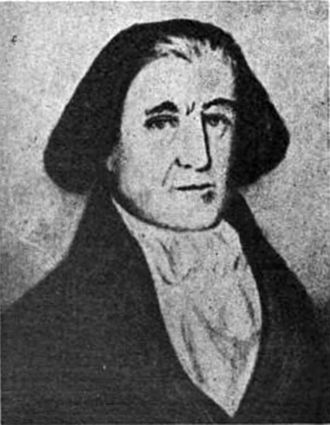

In May 1792, an American merchant ship captain named Robert Gray sailed into the Columbia River. He was the first American to explore this important river. His ship, the Columbia Rediviva, was privately owned.

This journey later helped the United States claim the Pacific Northwest. However, the British disagreed with this claim. Because of Gray's trip, the river was named "Columbia" after his ship. Captain Gray spent nine days on the river. He traded fur pelts with local people before sailing back out to sea.

Contents

Captain Gray's Journey

Captain Gray was a merchant ship captain from Rhode Island. He had already sailed around the world between 1787 and 1790. This first trip was for trading, starting from Boston, Massachusetts. He traveled to the north Pacific coast of North America to trade for furs. Then, he went to China to trade the furs for tea and other goods.

After his first big trip, Gray sailed to the northwest coast again. He left on September 28, 1790, and arrived in 1792.

Meeting Captain Vancouver

During his first voyage to the northwest coast, Gray was second-in-command of the Columbia Rediviva. The main captain was John Kendrick. Gray once tried to enter a large river mouth near 46 degrees north latitude. He spent nine days trying but could not get in. He then sailed north to Nootka Sound.

After spending the winter on Vancouver Island, Gray set sail again on April 2, 1792. On this trip, he saw muddy waters flowing from the shore. He thought it might be the "Great River of the West." While waiting for good weather, Gray met another ship on April 29. This was HMS Discovery, led by British naval captain George Vancouver. Captain Vancouver did not believe Gray had found a large, navigable river.

The large rivers and inlets described as flowing into the Pacific between 40 and 48 degrees north were actually small streams or bays too shallow for our ships.

- —Vancouver's log, April 28, 1792.

Gray told Vancouver that he had found a big river at 46 degrees 10 minutes latitude. He said he couldn't enter it because of the strong currents. But Vancouver still doubted it:

This was likely the opening I found on the 27th, and it was impossible to enter, not because of the current, but because of the waves that stretched across it.

Gray told Vancouver he would explore that area more. Then he sailed south, near the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Entering the Columbia River

The mouth of the Columbia River Estuary had dangerous, shifting sand bars. These made it very hard for any ship to enter. In April, Gray tried to enter the river, but bad weather stopped him.

After sailing north and meeting Vancouver, Gray returned to the river. This time, he sent a small sailboat ahead. Its job was to find a safe path across the sand bar by checking the water depth. This process is called sounding.

Finally, on the evening of May 11, 1792, Gray's men found a safe channel. The ship and crew then sailed into the Columbia River. Once inside, they sailed upriver. Gray named this large river "Columbia" after his ship. The local native people called the river "Wimahl," which meant "Big River."

Gray also named other places, like Adams Point and Cape Hancock. However, many of these places have different names today. The farthest Gray explored upriver is now called Grays Bay. The river flowing into it is Grays River. These names were given later by William Robert Broughton, one of George Vancouver's officers. Robert Gray had made a map of the bay and the river's mouth, and Vancouver later got a copy.

Life on the River

Once the Columbia Rediviva entered the river, many native people came alongside in their canoes. The crew got ready to fill their water barrels with fresh water.

When we were over the bar, we found this to be a large river of fresh water, up which we steered. Many canoes came alongside. At 1:00 P.M., we anchored in ten fathoms, on black and white sand. …People were busy pumping salt water out of our water barrels to fill them with fresh water, while the ship floated in. So ends.

- —Gray's log

The crew traded with the local people. They mainly exchanged nails and other small iron items for pelts, salmon, and meat like deer and moose. During their nine days on the river, the ship traded almost daily. The crew also did repairs and maintenance on the ship. They collected over 450 animal pelts to trade in China.

On May 14, the ship reached its furthest point inland, about 12–15 miles (19–24 km) upriver. The ship briefly got stuck because the crew had taken the wrong channel. The channel they were in ended. The Columbia Rediviva then slowly started to return downriver.

The next day, Captain Gray and his first mate, Mr. Hoskins, went ashore in a jolly-boat to explore the land. Gray "landed on the north riverbank, raised the American flag, planted some coins under a large pine tree, and claimed possession for the United States." By May 18, the ship was about six or seven miles (9.7 or 11.3 km) from the sand bar.

On May 19, the ship anchored near the native village of Chinoak, led by Chief Polack. On this day, Gray officially named the river "Columbia." He also gave names to other landmarks:

Capt. Grays named this river Columbia’s, and the North entrance Cape Hancock, and the South Point Adams.

Then, on May 20, Gray and his crew lifted anchor around 1 PM to sail for the ocean. Around 2 PM, they had sailed over the bar. By 5 PM, the Columbia Rediviva had left the river and reached the open sea. They sailed north along the coast. The next day, they passed Grays Harbor on their way to meet their smaller ship, the Adventure.

Before sailing to China, Gray and his crew returned to Nootka Sound. There, Gray shared news of his discovery with the Spanish commander, Quadra. Gray gave Quadra a map and description of the river's mouth. Captain Vancouver later got a copy of this in September. After leaving Nootka, the ship sailed for the China market.

What Happened Next

After exploring the Columbia River and trading with the native people, the ship and crew sailed to China to sell the furs. They returned to Boston in July 1793.

Gray's entry into the Columbia River was later used to support America's claim to the Oregon Country. This was during a disagreement with Britain called the Oregon boundary dispute. Both American and British leaders used many points to support their claims. Neither side fully agreed that the other had a clear right to the land. The British questioned if Gray's trip had any real value for claiming the land. The Americans argued against this. They could not agree on this or many other points about the Oregon Country. In the end, they reached a compromise with the Oregon Treaty in 1846.

When Gray first returned, his discovery was not seen as very important. He did not publish it, and no one knew how important it would become.

Grays Harbor, a place north of the Columbia's mouth, is named after Robert Gray. Today, Astoria, Oregon, is located on the south shore of the Columbia estuary. John Jacob Astor built his trading post there less than 20 years after Gray's discovery.

Because Gray named the river after his ship, the name "Columbia" is now used for many places in the Pacific Northwest. These include Columbia County, Oregon; British Columbia; Columbia Street in Portland, Oregon; and Columbia City, Oregon.

Previous Explorations

Bruno de Heceta (1775)

In 1775, a Spanish explorer named Bruno de Heceta (also spelled Hezeta) explored the northwest coast of North America. He was in charge of the ships Santiago and Sonora. On his way back south, with only the Santiago, Heceta found a large bay that went far inland. He tried to sail in, but the strong currents stopped him. His crew was too small to handle the anchor easily, so he couldn't wait for better conditions. He wrote that the strong currents made him think it was the mouth of a great river or a passage to another sea. He named the bay Bahia de la Asunciõn. He also made a map of what he could see from outside the Columbia bar. Later Spanish maps often showed the Columbia River's mouth with names like Entrada de Hezeta or Rio de San Roque.

John Meares (1788)

Captain John Meares explored the Pacific Northwest in 1788. He had a copy of a Spanish map that showed the Columbia River's mouth as Entrada descubierta por Dn Bruno Hezeta. On July 6, Meares sailed his ship, the 230-ton snow Felice Adventurer, to the river's mouth at the latitude shown on the Spanish map. But he could not find the entrance. He did see the cape on the north side and named it Cape Disappointment. This name showed his failure to find the river. Meares then wrote in his log: "We can now safely say that no such river as St. Roc exists, as shown on the Spanish charts."

The last known attempt to enter the Columbia River before Gray's successful trip was Captain Vancouver's visit in April 1792.

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |