John Kendrick (American sea captain) facts for kids

John Kendrick (1740–1794) was an American sea captain. He played a big role during the American Revolutionary War. He also explored and traded furs in the Pacific Northwest with his helper, Robert Gray. Kendrick led the very first United States expedition to this region.

He was involved in the 1789 Nootka Crisis. This happened when a Spanish officer, José Esteban Martínez, took over some British ships at Nootka Sound. This event almost caused a war between Britain and Spain!

Kendrick was also the first American to try to open trade with Japan. He even started the sandalwood trade in Hawaii. Sadly, he died when a cannon fired by accident during a friendly salute with another ship. John Kendrick was key in starting trade routes in the Pacific Northwest, the Hawaiian Islands, and China. He helped the young United States become a strong trading nation around the world.

Contents

Early Life of John Kendrick

John Kendrick was born in 1740 in what is now Orleans, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod. He was the third of seven children. His family had a long history of working on ships. His father, Solomon, was a whaling captain. John started sailing with his father when he was just 14 years old.

By his late teens, he was sailing with crews from Potonumecut, which is now part of Orleans. He had good relationships with the local native tribes, like the Wampanoag. This helped him make friends with native peoples in the Pacific Northwest later on.

When he was 20, John joined a whaling crew. In 1762, he served in the militia during the French and Indian War. He only served for eight months, like many others from Cape Cod.

In the 1760s, John stayed in Massachusetts while his father moved to Nova Scotia. Massachusetts was a place where people were starting to resist British rule. John might have been involved in protests against British taxes and actions, like the Boston Massacre in 1770. In late 1767, John married Huldah Pease, who also came from a family of sailors.

John Kendrick and the American Revolution

John Kendrick was one of the "Sons of Liberty" who took part in the famous Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773. He was a strong supporter of American independence. During the American Revolutionary War, he commanded a privateer ship called the Fanny. This ship had 18 guns and a crew of 104 men.

The Fanny attacked British ships and captured some of them. This made Kendrick famous and brought him wealth. In August 1777, the Fanny and another privateer captured two valuable British ships. These captured ships were taken to Nantes, France. This caused a big stir because France was not yet officially in the war. The incident helped France decide to join the war against Britain.

Kendrick returned home a hero in the fall of 1778. With money he received from the King of France, he bought a house and built the first public school in Wareham, Massachusetts. He lived there with his family for the winter.

In early 1779, he sailed to war again on a privateer he owned called the Count d’Estang. Near the Azores, a group of islands, he was captured by a British warship. The British forced most of his crew to join their navy. They eventually released Kendrick and 30 men in a small boat. They traveled to the Azores, then Lisbon, and finally returned to America with the French fleet.

Soon after returning, Kendrick sailed to the Caribbean on the ship Marianne. He captured at least one more valuable prize. He came home again just before the British surrendered at Yorktown in October 1781. By this time, he had six children. When the war ended in 1783, Kendrick went back to whaling and coastal shipping. Later, he became the commander of the first American ships sent to explore new lands.

The Columbia Expedition

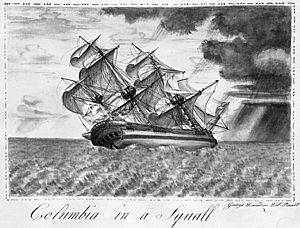

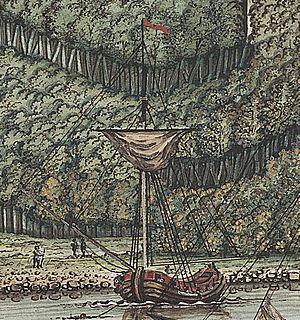

Not much is known about John Kendrick's life right after the American Revolution. In 1787, a group of merchants from Boston paid for an expedition called the Columbia Expedition. The ships for this trip were the Columbia Rediviva and the sloop Lady Washington.

Captain Kendrick, who was 47 years old, was given command of the larger ship, Columbia. The 32-year-old Robert Gray commanded the Washington. Kendrick was in charge of the whole expedition. The two ships had about 40 men, many of whom had fought in the Revolutionary War.

Simeon Woodruff, the oldest man on the trip, was the first officer of the Columbia. He had sailed around the world with James Cook and had already visited the Pacific Northwest, Hawaii, and China.

Joseph Ingraham, a 25-year-old veteran, was the second officer of the Columbia. He later became a captain himself. Robert Haswell, 19, was the third officer. He kept a journal that tells us a lot about the first two years of the trip. Kendrick also brought two of his sons, John Jr. and Solomon.

Journey to the Pacific 1787–1788

The Columbia Expedition left Boston Harbor on October 1, 1787. They reached the Cape Verde Islands on November 9. Here, Simeon Woodruff left the Columbia after an argument with Kendrick. Kendrick was unhappy with how the ship was loaded, which was Woodruff's job. Woodruff refused to help repack the ship, so Kendrick removed him from his position. Woodruff eventually returned to America.

This incident made Robert Haswell dislike Kendrick even more. Haswell had been friends with Woodruff. While at Cape Verde, Kendrick reorganized the Columbia's cargo. The ship carried supplies for two years and many trade goods, like mirrors, beads, and knives, to buy sea otter furs.

The journey continued on December 21, 1787. They reached the Falkland Islands on February 16, 1788. Here, they got water and prepared to sail around Cape Horn, a very dangerous part of the world.

Tensions between Kendrick and Haswell grew. One day, Haswell hit a sailor. Kendrick got angry and slapped Haswell, moving him to the common sleeping area. Haswell asked to leave the expedition, and Kendrick agreed, but no other ship appeared. At the Falkland Islands, Haswell was moved to the Washington to serve under Gray.

Kendrick decided to leave the Falklands on February 28, 1788, and sailed south towards Cape Horn. He tried to avoid a storm by sailing very far south, almost 400 miles south of Cape Horn. Through March, the ships faced cold, sleet, huge waves, strong winds, and icebergs.

On April 1, the winds changed, signaling dangerous weather. Kendrick had the Columbia speed up, and the Washington followed. But in the morning, with the storm still coming, the two ships lost sight of each other. For three more days of heavy storms, they were completely separated. The Columbia was badly damaged and driven back east.

The Washington continued through violent storms for ten days. Once the storm cleared, Gray was happy to be separated. He saw a chance to be free from Kendrick's command. Kendrick's orders said they should meet at Alejandro Selkirk Island if separated. Gray went there, arriving on April 22, 1788. He waited overnight but saw no sign of the Columbia. Gray decided he had followed orders and was now free to continue alone.

Gray needed water and wood, but there was no place to land at Alejandro Selkirk Island. So, he headed north to Ambrose Island, arriving on May 3. They found no water but caught fish, seals, and sea lions. Then Gray continued, passing far west of the Galápagos Islands.

Kendrick reached the meeting point at Más Afuera about a month after Gray had left. Kendrick had been told not to stop in Spanish areas unless it was an emergency. The Columbia needed repairs and was running out of water and wood. Kendrick decided to risk visiting Robinson Crusoe Island, where there was a small Spanish settlement.

Kendrick approached the harbor, stopping about a mile offshore. The Spanish governor, Don Blas Gonzales, saw the ship was in trouble. He sent a fishing boat with armed men. The Spanish officer, Nicholas Juanes, came aboard the Columbia. He saw the ten cannons but found the crew friendly. Kendrick said he needed a safe place for repairs and to get water and wood. Don Blas Gonzales was curious about this American ship, the first he had ever seen, and gave permission.

The Columbia docked near the fort. Kendrick met Gonzales, who found him friendly. Gonzales allowed Kendrick six days for repairs and supplies. The crew fixed the damaged mast, rudder, and leaks. They filled water barrels from a creek.

After four days, a Spanish supply boat arrived. Kendrick wrote a letter to Joseph Barrell, telling him about their situation and being separated from the Washington. He gave the letter to the captain of the supply boat.

After six days, Kendrick was ready to leave, but strong winds kept the Columbia at anchor until June 3. Meanwhile, the supply boat reached Valparaíso, where news of the Columbia led to orders to seize the ship. On June 12, a merchant ship was armed and sent to capture the Columbia. Another warship followed. But by then, the Columbia was sailing far off the coast, and the Spanish ships did not find her. Don Blas Gonzales was removed from his job for helping Kendrick.

The Spanish also sent warnings to Mexico City and to the Spanish missions in California. The messages described the Columbia and Washington and ordered that if either ship appeared, they should be seized and the crews arrested as pirates.

The crews of both the Columbia and Washington started to get scurvy as they continued north.

On August 2, 1788, the Washington crew saw land near the border of California and Oregon. After a brief meeting with some natives, they continued north, looking for a safe harbor. They sailed past many native villages before finding a safe harbor near Tillamook Bay. Many natives came to trade sea otter skins and fresh food, which helped with the scurvy. Haswell noted that these natives had smallpox scars and steel knives, meaning they had met traders before. On August 13, Gray anchored the Washington in a protected inlet.

The ship stayed for five days. Many natives came to trade, and parties went ashore for water and wood. Gray decided to leave, but the Washington got stuck on a rocky reef. While waiting for high tide, a party went ashore, and a fight broke out. Crewmember Marcus Lopius was killed, and officers were wounded. Native war canoes tried to capture their small boat. The Washington got free but then got stuck again on a sandbar. The next day, August 18, it got free again. The ship used its small cannons to keep the war canoes away and escaped to the open ocean. Gray set course for Nootka Sound, far to the north.

Soon after, two Spanish warships, the Princesa and the San Carlos, sailed past but did not see the Washington. Two weeks later, they passed the Columbia, again without seeing it. The next year, these Spanish ships would be at Nootka Sound with Kendrick and Gray, starting the Nootka Crisis.

Nootka Sound 1788–1789

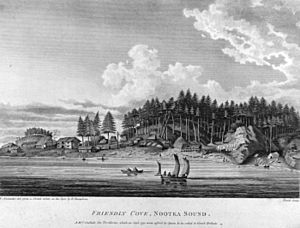

The Washington arrived at Friendly Cove in Nootka Sound on September 16, 1788. Another ship, the British Felice Adventurer, was already there. Two more British ships arrived soon after. All these ships were part of a fur trading business. After a few days, the British ships left, and on September 22, Kendrick's Columbia arrived. Kendrick took command of both his ships again. On October 26, 1788, the remaining British ships left for Hawaii and China. Kendrick then announced that his expedition would spend the winter in Nootka Sound. He wanted to make friends with the local Nuu-chah-nulth people to get an advantage in the fur trade. During the winter, Kendrick became friends with Nuu-chah-nulth chiefs Maquinna and Wickaninnish.

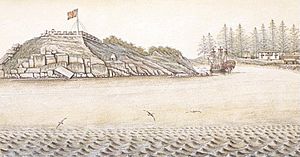

After winter, Kendrick sent the Washington under Gray on a short trading trip south. Gray collected many sea otter pelts and found the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca before returning to Nootka Sound on April 22. Gray found a British ship, the Iphigenia, anchored there. Kendrick had moved the Columbia to a cove called Marvinas Bay, deeper into Nootka Sound. He had built a small fort there with a house, a gun battery, and a blacksmith shop. Kendrick called it Fort Washington. It was the first US outpost on the Pacific coast. Kendrick wanted it to be a base for American trade in the Pacific Northwest. Over the summer, Kendrick used this outpost and his friendships with the Nuu-chah-nulth to collect many furs.

Kendrick decided that the Columbia was too big for trading close to the coast. The smaller Washington was better. So, the Washington was prepared for another trading trip. The British captains realized Kendrick controlled the fur trade around Nootka Sound. So, one British ship went north, and another prepared to follow. On May 2, Gray took the Washington north as well.

While sailing, Gray met the Spanish warship Princesa, commanded by Esteban José Martínez. Martínez had come to claim Nootka Sound for Spain. He told Gray that they were in Spanish waters. Gray made excuses, but Martínez let them go, knowing Kendrick's main ship, the Columbia, was trapped in Nootka Sound.

Martínez anchored in Friendly Cove, Nootka Sound, on May 5, 1789. Kendrick soon arrived and met with Martínez. Kendrick pretended that the Columbia was badly damaged and his crew sick, and they had only stopped for repairs. He said he had built a house and gun placement for protection. He readily accepted Spanish authority and said he would leave once his ship was fixed.

Kendrick saw Martínez's arrival as a chance to help his own goals. He treated Martínez with respect and offered his blacksmith's help. He also introduced Martínez to the local Nuu-chah-nulth. Some later said Kendrick and Martínez made a deal against the British. It's not clear if Kendrick agreed to seize British ships, but Martínez did tell Kendrick he planned to arrest British captains. Kendrick had a reason to encourage conflict between Spain and Britain, as it would reduce British competition in the fur trade and give him more time to set up an American base.

On May 12, 1789, another Spanish ship arrived. With more strength, Martínez seized the British ship Iphigenia and arrested its crew. This worried Chief Maquinna, who moved his people away from Friendly Cove. After a few weeks, Martínez released the Iphigenia after its captain agreed to certain conditions. Kendrick and his officer Ingraham were witnesses. Martínez made the captain promise to leave the Pacific Northwest and never return, a promise he broke. On June 8, 1789, another British ship, the North West America, returned. Martínez took it as security for debts.

On June 15, 1789, a small British ship, the Princess Royal, arrived. It needed repairs and couldn't resist Martínez. Robert Gray returned to Nootka Sound on June 17, finding the Spanish in control. Gray sailed the Lady Washington directly to Kendrick's outpost. Kendrick had collected many furs while Gray was away. Thinking they would leave soon, Kendrick took both the Columbia and Washington to Friendly Cove on June 28. On July 2, Martínez let the Princess Royal leave. Within hours, a larger British ship, the Argonaut, arrived.

Martínez and the British captain argued, each claiming Nootka Sound for their country. Kendrick, knowing Martínez planned to seize the Argonaut, prepared for possible violence. The next day, Martínez arrested the British captain. Martínez had his cannons ready and asked Kendrick to do the same with the Columbia, which he did. Seeing the Argonaut trapped, the British captain realized resistance was useless.

These events in the summer of 1789, especially the seizure of the Argonaut, led to the Nootka Crisis. When the news reached Europe, it almost caused a war between Britain and Spain.

Northwest Coast 1789

On July 13, 1789, the day after Martínez seized the Princess Royal, the Nuu-chah-nulth leader Callicum, Maquinna's son, went to Friendly Cove. He angrily called out to Martínez, who shot him dead. This event made the relationship between the Spanish and Nuu-chah-nulth much worse. Maquinna fled. The next day, Kendrick decided it was time to leave Nootka Sound.

Kendrick asked Martínez if he could return next year. Martínez agreed, with some conditions. Martínez asked Kendrick to take the prisoners from the North West America to Macau, offering furs for the cost. He also asked Kendrick to sell some furs for him in Macau. Kendrick wrote a short letter to Joseph Barrell, knowing the Spanish might read it.

Kendrick's son, John Jr., decided to stay at Nootka Sound and join the Spanish Navy. An officer described Kendrick crying as he said goodbye to his son.

On July 15, the Columbia and Washington left Nootka Sound. Instead of sailing north, they went south to Clayoquot Sound, where they stayed for two weeks. They anchored near Opitsaht, a large native village. Trading began right away.

While at Clayoquot Sound, Kendrick and Gray switched ships. Kendrick ordered Gray to take the Columbia to China. Kendrick would take the Washington north to trade for furs. Kendrick realized that with the British out of the fur trade because of the Nootka Crisis, Americans had a great chance. All the furs from the Washington were moved to the Columbia. On July 30, Gray sailed the Columbia out of Clayoquot Sound, heading for Hawaii and China.

The reason for switching ships is not fully known. One idea is that Kendrick thought the Washington was easier to handle because it was smaller. Gray later returned to Boston and on a second trip, he would enter the Columbia River, which was then named after his ship.

Kendrick's movements after leaving Clayoquot Sound are not fully known. The next confirmed report is from September, about a month later. Kendrick met another ship near Dundas Island. He then sailed to Haida Gwaii, a group of islands. He likely stopped at several Haida villages. At Anthony Island, he traded with the Haida village of Ninstints, led by Chief Koyah.

While Kendrick was trading at Ninstints, some minor thefts from his ship caused problems. One day, Kendrick's clothes were stolen. Kendrick held Chief Koyah and another chief hostage until the stolen goods were returned. Most items were returned. Kendrick then demanded all remaining furs be brought for trade. Some say he paid fairly, others say he forced the Haida to accept a lower price. After this, the chiefs were released, and Kendrick left. This incident caused Koyah to lose his chieftainship.

Two years later, when Kendrick returned, the Haida had not forgotten this treatment. A battle happened, and the natives captured the Washington's arms chest. Kendrick and his crew had to retreat below deck. Kendrick and his officers fought off the attack, killing many natives with cannons and small arms fire as they retreated.

Hawaii 1789

Kendrick arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in November 1789. The Lady Washington was the 15th Western ship known to visit Hawaii after James Cook. Kendrick sailed around the Island of Hawaii and anchored in Kealakekua Bay, where Cook had been killed. Native Hawaiians came to trade. Kendrick asked for Chief Kaʻiana, who had been friendly to him at Nootka Sound. Kaʻiana brought Kendrick a letter warning of native trickery. Kendrick also learned about the changing political situation in Hawaii. Chief Kamehameha I was growing in power and wanted firearms. Kendrick was careful about trading firearms but probably gave a few for supplies.

During his stay, Kendrick recognized sandalwood. Knowing it was valuable in China, he asked Kamehameha for permission to leave men to harvest it. Kamehameha wanted help training his men with firearms. They made a deal, and Kendrick left his carpenter, Isaac Ridler, and two other men.

After leaving Kealakekua Bay, Kendrick sailed through the islands. He stopped at Kauai and Niihau for water, yams, and hogs. Then he sailed for Macau, China.

Soon after Kendrick's visit, another trader killed about a hundred Hawaiians in an event called the Olowalu Massacre. Around the same time, a small ship was attacked, and its survivor, Isaac Davis, came under Kamehameha's control. Kendrick's three men, along with Davis and another man left by a trader, John Young, survived by serving Kamehameha. They taught Hawaiians how to use muskets and sail ships. This helped Kamehameha invade Maui and begin his conquest of all the Hawaiian Islands.

Macau 1790–1791

Kendrick anchored near Macau on January 26, 1790. Gray had arrived earlier and was at Whampoa, a trading center near Guangzhou (Canton). Both captains found trading difficult under the Canton System. Kendrick wrote to Gray for advice. Gray suggested Kendrick go to a smuggling area called Dirty Butter Bay. Gray also sent letters from Joseph Barrell, the owner of their venture. Barrell's letters were friendly and confirmed Kendrick was still in charge.

Kendrick took the Lady Washington to Dirty Butter Bay on January 30, 1790. He found it full of illegal activity. Gray suggested Kendrick sell his cargo to Gray's agent, but Kendrick refused. Kendrick asked Gray for a full account of the cargo sold and goods bought, but Gray refused to give him this information. Gray told Barrell he had sold 700 skins, but it was later found he had sold 1,215. Gray's cargo sold for a low price, and he bought cheap tea, much of which spoiled. Barrell lost money on Gray's first voyage.

Before Gray left China, Kendrick sent him artifacts from the Pacific Northwest Coast for a new museum in New England. Gray ignored Kendrick's requests for financial details. On February 9, 1790, Gray left Whampoa. He anchored near the Lady Washington but avoided contact. On February 12, he left for Boston.

Kendrick became very ill with a fever and fell into debt. But by spring, he recovered. He sold the furs for a much better price than Gray had. With cash, he paid his debts and rented a house in Macau. He had the Lady Washington rebuilt into a brigantine, similar to a ship he commanded during the Revolutionary War.

Kendrick found himself stuck in Macau. The Chinese would not let him leave, and the Portuguese Governor would not help. The reason for this is unclear. Kendrick asked William Douglas for help. Douglas was now captain of an American ship. Kendrick and Douglas formed a partnership. Douglas agreed to pick up Kendrick's sandalwood in Hawaii on his way back.

Around this time, John Meares arrived in London and started stirring up trouble about the Nootka Crisis. Meares claimed Kendrick was behind the Spanish seizing British ships. News of a possible war between Britain and Spain reached Macau in the summer of 1790. Kendrick was arrested by soldiers and ordered to leave. He went back to the Washington in Dirty Butter Bay.

On August 9, 1790, Gray returned to Boston with the Columbia. There were big celebrations for this first US trip around the world, and Gray became a national hero. However, the trip was a financial failure. Gray and Haswell blamed Kendrick. Newspapers published articles calling Kendrick a rogue and a cheat. He was also blamed for the Nootka Crisis.

Gray proposed another trip where he would command the Columbia without Kendrick. While the Columbia was being prepared, controversy grew over Kendrick's role. On October 2, 1790, the Columbia left Boston with Gray as captain.

On October 28, 1790, the First Nootka Convention was signed, preventing a British-Spanish war. Spain agreed to pay for the seized ships and return land. George Vancouver was to sail to Nootka Sound to carry out the agreement.

Kendrick remained stuck at Dirty Butter Bay. In late 1790, a new governor of Macau was appointed, and Kendrick was finally allowed to leave. By this time, Douglas had returned with furs, Kendrick's Hawaiian sandalwood, and Kendrick's men. After selling the goods, the two captains decided to sail to Japan to try to open trade there. They left China on March 31, 1791.

Japan

Kendrick left Macau in March 1791 with William Douglas. They decided to try to trade with Japan, which was mostly closed to foreign trade under its sakoku policy. Kendrick and Douglas reached the Kii Peninsula of Japan on May 6. They sailed into a channel to escape a typhoon. Japanese fishermen visited their ships. Kendrick offered food and drink. The Chinese crewmen on board could communicate by writing. Kendrick and Douglas learned there was no market for sea otter furs in Japan, which was different from what they had heard. The fishermen also told them not to go to Osaka, where they would be arrested.

While they waited for good weather, five men went ashore for water and wood. They fired a warning shot at a farmer who tried to stop them. Meanwhile, messages reached the local lord, who sent samurai warriors. On May 17, Kendrick and Douglas left, perhaps hearing the troops were coming. The samurai arrived two days later.

This first visit by Americans to Japan was important for the United States. For Japan, it led to new alarms and coastal patrols, making Japan even more isolated.

A few days later, Kendrick and Douglas found some islands not on their maps. They named them the "Water Islands." Here, they decided to separate. Douglas sailed to Alaska, and Kendrick headed for the Pacific Northwest coast.

Northwest Coast 1791

In early June 1791, Kendrick arrived at Bucareli Bay. He spent about a week trading in Tsimshian and Haida territory. He visited several villages in Haida Gwaii.

On June 13, he visited the Haida village X̱yuu Daw Llnagaay, near Ninstints. This was in the territory of Chief Koyah, with whom Kendrick had had trouble in 1789. Trading went well for a couple of days, and many Haida came. Kendrick relaxed his security. He was told Koyah was no longer a chief, and Koyah seemed to hold no bad feelings.

Kendrick allowed about 50 Haida, men and women, aboard his ship. Koyah joined them, bringing his own furs to trade. Some say Kendrick traded a blue coat to Koyah.

During the trading, one of the Haida chiefs, perhaps Koyah, took control of a weapon chest. Haida warriors, in what seemed like an unplanned attack, drew knives and threatened the crew. The crew retreated below deck. Haida canoes crowded alongside the Washington, and more warriors boarded. Some accounts say Koyah taunted Kendrick, who was alone on the quarterdeck. Kendrick tried to bargain, offering to pay the Haida to leave, but it didn't work. While the men below were getting weapons, Kendrick and Koyah fought near the stairs. Koyah wounded Kendrick twice with his knife. Crewmembers started firing at the Haida warriors. Kendrick got a pistol from his cabin and led the crew back on deck. A hand-to-hand battle followed. About 15 Haida, men and women, were killed. The crew fired at the retreating Haida with muskets and cannons. Many Haida died. Koyah was shot but survived. His wife and child were killed, according to some stories.

This battle became a famous story, with different accounts of Kendrick's actions.

Kendrick left immediately and went to Bucareli Bay. He and his crew spent a few weeks recovering before sailing to Nootka Sound. He didn't know about the Nootka Convention that had been signed, preventing war. Kendrick entered Nootka Sound ready for a fight, with cannons loaded. The Spanish officer Salvador Fidalgo had re-established the fort at Friendly Cove. The acting commander sent a boat, telling Kendrick that Nootka Sound belonged to Spain. Kendrick defiantly said they had come to trade and would do so. The Spanish commander decided to wait for Fidalgo to return. Kendrick arrived at his old base in Marvinas Bay on July 12.

At Marvinas Bay, Kendrick was welcomed by the native Nuu-chah-nulth. Their friendship had lasted and was even stronger because they were still frustrated with the Spanish. Kendrick began to make alliances with chiefs Maquinna, Claquakinnah, Wickaninish, and others. He learned about the Nootka Convention and that British traders would be allowed back. Kendrick hoped a strong alliance with the natives could help him compete with the British.

Many chiefs gathered at Marvinas Bay. Kendrick entertained them with Chinese fireworks. Then he gave a speech, saying that Europeans wanted to build settlements. He told them that if he held deeds to their land, it could stop Europeans from staying permanently. Kendrick promised they would keep all their traditional rights. He also promised to defend the lands against other traders and tribes. Most importantly, he offered them firearms. This would help them defend themselves against traders who had previously raided villages. The memory of Maquinna's brother Callicum being shot by the Spanish was still fresh.

The chiefs agreed to Kendrick's plan. In July 1791, Kendrick bought Marvinas Bay and the surrounding land from Maquinna and other chiefs. He then went to Tahsis, deeper into Nootka Sound, and made a similar agreement. He then sailed the Washington through the narrows north of Nootka Island into Esperanza Inlet, avoiding the Spanish fort. In Esperanza Inlet and Nuchatlitz Inlet, he made two more land purchases.

In early August 1791, Kendrick sailed south to Clayoquot Sound. Chief Wickaninnish, having heard of Kendrick's actions, was waiting to make a similar deal for land and firearms. On August 11, 1791, Wickaninnish and other chiefs gave Kendrick control of almost all the land around Clayoquot Sound. The deed mentions only four muskets traded, but by 1792, Wickaninnish was said to have about 200 muskets from Kendrick. Kendrick's land purchases gave him control of over 1,000 square miles of Vancouver Island. After these purchases, Kendrick built a new Fort Washington on an island in Clayoquot Sound.

On August 29, 1791, the Columbia arrived at Clayoquot Sound, on its second voyage to the Pacific Northwest. Robert Gray was captain and no longer under Kendrick's command. John Hoskins was the supercargo, sent by Joseph Barrell to manage the business.

From Hoskins, Kendrick learned about other traders on the coast. These ships were mostly trading in the north, as Kendrick had already bought most of the furs on Vancouver Island. Joseph Ingraham later wrote that natives around Nootka Sound always asked about Kendrick, saying they had furs for him and would not sell to anyone else.

The day after arriving, some officers from the Columbia visited Kendrick's Fort Washington. Hoskins described it as a rough log outpost with an American flag flying. The Lady Washington was being repaired for a trip to Hawaii and China. Kendrick received a letter from Joseph Barrell, learning that the Columbia was no longer under his command. Kendrick offered Hoskins 1,000 furs for payment for his men and his Macau debts, which were about $4,000. Hoskins said he didn't have the authority. So, Kendrick decided to continue on his own with the Washington.

Gray planned to spend the winter in Clayoquot Sound, using Kendrick's strategy from the first voyage. Kendrick helped tow the Columbia to a cove for the winter. After Kendrick left, Gray built his own outpost called Fort Defiance. On September 29, 1791, Kendrick sailed for Hawaii. Over the winter, Gray struggled to keep the friendship with Wickaninnish's people that Kendrick had built. In one incident, Gray took Wickaninnish's brother hostage. Later, Gray's Hawaiian servant ran away. In revenge, Gray took another hostage.

Toward the end of winter, Gray thought there was a plot to attack his outpost. So, Gray decided to destroy Opitsaht, the main native town of Clayoquot Sound. As the Columbia left Clayoquot Sound in March 1792, Gray ordered a bombardment that completely destroyed Opitsaht. The town was empty, but it had over 200 beautifully carved buildings. Wickaninnish's people remained loyal to Kendrick, but Gray's actions ruined their good feelings toward American traders.

Hawaii and Macau 1791–1793

Kendrick arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in late October 1791. He met with King Kamehameha. By January 1794, he had given his carpenter, John Boyd, to Kamehameha's service. Boyd began building a 40-ton armed sloop for Kamehameha.

As the work continued, Kendrick toured the islands, trading and meeting the men he had left behind. Kendrick learned from Kamehameha that Vancouver and Brown were trying to get the islands for the British Crown. Kendrick returned to Kealakekua Bay and began making plans to stop Vancouver and Brown.

On January 9, 1794, Vancouver's ships passed Kealakekua Bay on their way to meet Kamehameha. Vancouver learned about Kendrick's shipwright, John Boyd, and the ship being built. This worried Vancouver because he had refused Kamehameha's request for a ship. Vancouver also learned Kendrick was at Kealakua Bay, with Kamehameha's advisor John Young. Vancouver tried to get Kamehameha to come with him to Kealakekua Bay to stop Kendrick. Kamehameha at first refused.

Vancouver felt he needed Kamehameha to stop Kendrick. After much convincing, Kamehameha agreed to go with Vancouver. On the way, Vancouver convinced Kamehameha to let him take over the ship construction. He said Boyd was not skilled enough and offered to build the ship himself. Vancouver declared the ship, to be named Britannia, would be a "man-of-war." Kamehameha was pleased.

Vancouver's ships neared Kealakekua Bay on June 12, 1794. John Young brought a welcome letter from Kendrick's agent, John Howell, who was living ashore. As Vancouver's ships entered the bay, Kendrick raised the US flag. Kendrick's 90-ton Washington was much smaller than Vancouver's ships. Vancouver's men, over 180, far outnumbered Kendrick's crew of less than 30.

The next day, Kendrick, John Howell, and a Hawaiian chief went aboard Vancouver's ship. Vancouver and Kendrick met for the first time. Kendrick told Vancouver he was wintering in Hawaii and planned to return to the Pacific Northwest in the spring. Howell would stay in Hawaii to manage Kendrick's business. Vancouver knew Kendrick had already sailed among the islands, strengthening his ties with the Hawaiians. Kendrick had acquired a huge feathered war cloak, trading his two stern cannons for it. He also got valuable chunks of ambergris. His men on Kauai were collecting sandalwood and pearls and making molasses.

The next day, Kendrick and Howell dined with Vancouver again. Kendrick wanted to talk about William Brown and his ships. Kendrick knew Vancouver, as a Royal Navy officer, had rules, while Brown, a private merchant, was free to do as he pleased.

On February 1, 1794, Vancouver's carpenters began working on the promised warship for Kamehameha. With Kamehameha pleased, Vancouver restarted talks about Hawaii becoming part of the British Crown. Many chiefs met with Vancouver. At a second meeting, Kamehameha agreed to give the island to Britain, according to Vancouver. But when Vancouver asked for all of Kendrick's men to be removed, Kamehameha and the other chiefs refused.

Despite Vancouver's efforts, Kendrick continued as if nothing had happened. He ignored both Vancouver's claim over Hawaii and Brown's claim over other islands.

Vancouver left Kealakekua Bay on February 26, 1794. He cruised among the islands, trying to increase British influence and drive Kendrick away. Kendrick, however, sailed ahead, arriving at key harbors and meeting with chiefs before Vancouver. He spent five days at Waikiki with Chief Kahekili. When Vancouver arrived, the chiefs would not even meet with him.

When Vancouver reached Kauai, he found Kendrick already there. Vancouver met with Kendrick and tried to pressure him to remove his men. Kendrick pretended to agree, and Vancouver thought he had succeeded. But when Vancouver finally left for the Pacific Northwest on March 14, 1794, Kendrick and his men remained in Hawaii.

On February 24, 1794, Brown had sailed from China for the Pacific Northwest. Vancouver and Brown met on July 3, 1794, near Cross Sound, Alaska. Brown had just arrived with the Jackall. Vancouver told him about his failure to drive off the Americans in Hawaii.

Not long after Vancouver left Hawaii, Kendrick also sailed to the Pacific Northwest. He found the situation at Nootka Sound difficult. Chief Maquinna's people had suffered a hard winter. The conflict with Wickaninnish was ongoing. Maquinna wanted to move closer to the Spanish fort, but the new commander refused. Kendrick soon sailed north, looking for sea otter skins, which were scarce. He acquired furs in the Alexander Archipelago. At the Tlingit settlement that would become Sitka, he sold all his remaining trade goods. Then he headed back to Nootka Sound.

In early September 1794, Kendrick was anchored in Friendly Cove, Nootka Sound. Three Spanish ships and two British trading ships were also there. Vancouver and his three ships soon arrived. Kendrick found his eldest son, John (now called Juan Kendrick), was there as master of a Spanish ship. He also learned that the Resolution had disappeared, and his son Solomon was probably dead. Neither John nor Juan knew that the Resolution had been attacked and captured by Chief Cumshewa and possibly Kendrick's old enemy Koyah. All but one of the crew were killed, including Solomon Kendrick. Juan Kendrick learned about this later and took revenge in 1799.

At Friendly Cove, Kendrick continued to prepare the Washington for another trip to China. It would be his fifth voyage across the Pacific Ocean. He had two seasons of furs and over 80 pounds of ambergris from Oahu, which alone was worth about $16,000 in Macau. Awaiting him in Macau was a letter from Joseph Barrell offering Kendrick ownership of the Washington and full independence if Kendrick could send 400 chests of tea. But Kendrick would be killed before reaching Macau.

In September 1794, Juan Kendrick was given command of a Spanish ship and sailed for San Blas. On the way, he stopped at Monterey, California, becoming the first American known to have set foot in California.

On October 5, 1794, William Brown arrived on the Jackall. He learned he could no longer count on help from Vancouver, who was soon returning to England due to poor health.

On October 16, 1794, Vancouver left for Monterey. The next day, the Spanish also left, abandoning their outpost at Nootka Sound, as required by the Third Nootka Convention. Brown's ships soon left for Oahu, leaving only the Lady Washington and a Spanish supply ship. Around the end of October 1794, Kendrick finally sailed for Hawaii.

Hawaii and Death

The story of John Kendrick's death has been told in many ways. The earliest account comes from the log of Captain John Boit, who heard it from John Young just 10 months after the event. Boit wrote:

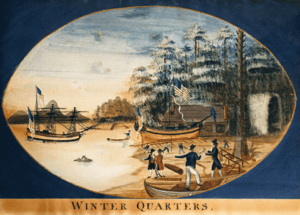

- On December 3, Captain John Kendrick in the ship Lady Washington arrived at Fairhaven and was welcomed by Captain Brown.

- On December 6, a battle was fought between the chiefs of Oahu and Kauai. The King of Oahu won with Kendrick's help.

- Kendrick told Captain Brown that the next morning he would raise the United States flag and fire a salute. He asked Brown to answer it with his two English ships. Brown agreed and prepared three guns.

- Around ten the next morning, the ship Jackal began to salute. But the third gun was not primed. So, the fourth gun was fired. It was loaded with cannonballs and grapeshot. It went through the side of the Lady Washington and killed Captain Kendrick as he sat at his table. It also killed and wounded many on deck.

James Rowan, the mate of the Lady Washington, later said that he had sworn he would never salute a vessel in a hurry again, "except at a safe distance."

Another account comes from Sheldon Dibble, a missionary in Hawaii from 1836 to 1845. He heard local stories about the battle. According to Dibble:

- Captain Brown helped in the war, but Captain Kendrick did not.

- The first battle was at Punahawale, where Kaeo and some foreigners won.

- The next battle was at Kalauao. Captain Brown and his men helped Kalanikupule win, and Kaeo was killed.

- When they returned to Honolulu, Captain Brown fired a salute to celebrate Kalanikupule's victory.

- The American ship was anchored only a few yards away. Captain Kendrick was eating dinner in his cabin.

- A wad, probably from one of the guns, went into the cabin and hit him in the head, killing him instantly.

- Foreigners on one of the ships investigated the case. They decided it was an accident.

It is believed that Kendrick's body was buried in the same place as Captain Derby (1802) and Isaac Davis (1810). This spot later became a cemetery for foreigners near King Street and Pi'ikoi Street in Honolulu. John Howell, the clerk on the Lady Washington, is thought to have led Kendrick's burial service.

Nineteen days after Kendrick's death, a group of Kalanikūpule's warriors attacked from canoes. They killed Brown and many of his men. The survivors managed to escape to Kealakekua Bay with the ships.

Any journals, logs, and other papers Kendrick had kept over the years were lost.

Legacy of John Kendrick

Because John Kendrick's own journals were lost, his story has been put together from other sources. These include Haswell's journal and papers from the people who paid for the expedition.

Soon after his death, Americans became very important in the maritime fur trade that Kendrick had helped start. Many who followed him praised him. Kendrick's harbor at Marvinas Bay, also called Kendrick's Cove, became a common place for American ships to anchor on the Northwest Coast.

Kendrick Bay and Kendrick Islands in southern Prince of Wales Island, Alaska, are named after John Kendrick. Several places in British Columbia are also named for him, including Kendrick Inlet in Nootka Sound and Kendrick Point in Haida Gwaii.

The Kendrick House, built around 1800, is in South Orleans, Massachusetts. The John Kendrick Maritime Museum in Wareham, Massachusetts, displays some of Kendrick's personal items. The Kendrick Woods Conservation Area and John Kendrick Road are also in Orleans, Massachusetts.

See also

In Spanish: John Kendrick (marino estadounidense) para niños

In Spanish: John Kendrick (marino estadounidense) para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |