Robert Pike (settler) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Pike

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | 1616 Wiltshire, England

|

| Died | 1706 (aged 89–90) |

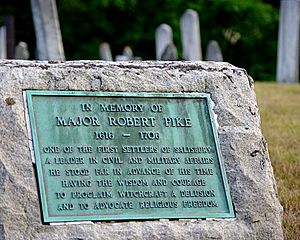

| Monuments | Old Colonial Burying Grounds in Salisbury, Massachusetts, United States |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Sanders |

| Children | Eight |

| Parent(s) | John Pike (father) |

Robert Pike (1616–1706) was an important person in early American history. He is best known for standing up against the Salem witch trials in 1692. Before that, he was involved in two other big public disagreements. First, he openly spoke out against how the Quakers were treated. For this, he was questioned by the government of Massachusetts in 1653. Later, he had a long argument with the minister of Salisbury, Reverend John Wheelwright. The minister even removed Pike from the church in 1675, but later had to let him back in.

Contents

Robert Pike's Early Life

Robert Pike was likely born in Landford, Wiltshire, England, around 1616. He moved to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635 with his father, John Pike (1572–1654), and four brothers and sisters. His mother, Dorothy Day, had passed away a few years before. The family first settled in Newbury.

Within a few years, Robert Pike moved to the east side of the Merrimack River. He became one of the first people to own land and help start the town of Salisbury. This town was first called Colchester. He lived there for the rest of his life.

Pike married Sarah Sanders from Salisbury on April 3, 1641. They had eight children together before Sarah passed away in 1679. We don't know much about his schooling in England. However, it's clear he was well-educated. He wrote clearly and could make strong arguments to defend himself and others. His brother, John Pike (1613–1689), also seemed to be well-educated before they arrived in 1635.

Robert Pike's Public Service

As one of the main leaders in the new settlement of Salisbury, Robert Pike took on many important jobs. These included roles in town government and the military.

Early Town Roles

In 1641, his first job was as a fence viewer. This person helped settle arguments about property lines and fences. They also made sure fences were strong enough to keep livestock in. In May 1644, the General Court (the colony's government) chose him and two others to "end small causes in Salisbury." This job was similar to a justice of the peace today, someone who handles minor legal issues.

Military Leadership

By 1646, Pike was the leader of the local militia, which was like a local army. He was known as Lieutenant Pike, and later as Major Pike. Thomas Bradbury, whose wife was Mary Bradbury, was his second-in-command.

Serving in Government

In 1648, Salisbury elected Pike to be a Deputy to the General Court in Boston. He was re-elected 10 times! Later, he served one term as a magistrate, which is a judge. During King Philip's War (1675–78), Pike was a Sergeant-Major. He was in charge of a large area north of Boston, including what is now Maine.

Defending the Quakers

Small groups of Quakers, a religious group, began arriving in New England around 1656. The Puritan leaders of the General Court quickly made laws to stop their activities. These new laws meant harsh punishments for anyone who followed Quaker beliefs. They even punished ship captains who brought Quakers as passengers.

However, these new laws caused big debates within the General Court. Not everyone agreed with them. Leaders like Robert Pike, who represented towns outside of Boston, were more likely to believe in religious freedom. They probably voted against the new laws. Still, many Quaker missionaries were punished. They faced public whippings, being sent away from the colony, and even the threat of death if they returned. Between 1659 and 1661, five Quakers were hanged in Boston because they returned to preach publicly.

Pike's Stand in Dover

In the winter of 1662, three Quaker women arrived in Dover, New Hampshire, to preach. They were quickly arrested and ordered to be whipped. Richard Waldron, a judge in Dover, even issued a special order. It said that the police officers (called constables) in 11 nearby towns, including Salisbury, had to whip the three women publicly.

The women were put in a cart and taken to Salisbury, which was the third town on their route. But in Salisbury, the local leaders, including Thomas Bradbury, Walter Barefoote, and Robert Pike, set them free! Historians aren't sure of all the details. But it's believed that Pike was the local constable. He may have given Barefoote the authority to free the women.

More than 200 years later, the Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier wrote a famous poem about this event called "How the Women Went from Dover." One part of the poem is carved on a stone memorial to Robert Pike in Salisbury Common:

"Cut loose these poor ones and let them go;

Come what will of it, all men shall know

No warrant is good, though backed by the Crown,

For whipping women in Salisbury town!"

Records show that Major Pike was one of the owners of Nantucket Island. He helped give this island to the Quakers as a safe place where they would be less likely to be treated badly.

Robert Pike and the Salem Witch Trials

By 1692, Robert Pike had become an Assistant to the General Court. In this role, he was told to record statements from both the accused people and those accusing them during the Salem witch trials. This was for the area around Salisbury.

Susannah Martin and Mary Bradbury

In May, Pike took notes about the stories and accusations against Susannah Martin from nearby Amesbury. More statements against her followed in June. She was found guilty in Boston in late June. Then, on July 19, she was executed by hanging, along with Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Elizabeth Howe, and Sarah Wildes.

On May 26, 1692, George Herrick brought charges against Mary Bradbury of Salisbury. He did this on behalf of Ann Putnam and Mary Walcott. Mary Bradbury was the wife of Thomas Bradbury. She was well-known and respected by Robert Pike and many others. She was found guilty in her final trial on September 9. This happened even though several people spoke up for her, and 115 townspeople signed a petition to support her. Pike himself prepared a sworn statement for her, defending her good character and actions.

Questioning the Trials

Before Mary Bradbury was found guilty, Pike wrote an important letter to Jonathan Corwin, one of the judges in the trials. In this letter, he made a strong and logical argument against using "spectral evidence" and the statements of the "afflicted girls." Spectral evidence was when people claimed they saw the ghost or spirit (specter) of an accused witch harming them.

Pike, like most Puritans, believed that witches and witchcraft were real and were the work of Satan. However, he questioned how the court was deciding who was guilty. In his letter from August 9, Pike made several key points:

- He said that anyone, good or bad, could be a witch.

- He argued that having a bad reputation didn't mean someone was guilty (like with Sarah Good).

- He pointed out that Satan could make anyone's specter appear to a tormented person, not just a witch's specter.

- He asked how anyone could know if Satan was acting with or without the permission of the accused person.

- He also said it didn't make sense for a witch to practice witchcraft inside a courtroom.

- He thought it was strange for witches to accuse others of witchcraft. He believed they were all part of Satan's kingdom, which would fall apart if they fought among themselves.

We don't know exactly how Pike's letter was received, as there is no written reply. But with this letter, he became one of the first important men to question how the witchcraft crisis was being handled. Within a few weeks, Thomas Brattle and Samuel Willard of Boston wrote their own papers, using some of the same arguments Pike had made. By October 1692, the court's activity slowed down a lot, the executions stopped, and the witchcraft crisis was effectively over.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |