Rudolf Vrba facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rudolf Vrba

|

|

|---|---|

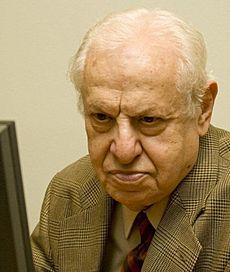

Vrba in New York, November 1978, during an interview with Claude Lanzmann for the documentary Shoah

|

|

| Born |

Walter Rosenberg

11 September 1924 Topoľčany, Czechoslovakia

|

| Died | 27 March 2006 (aged 81) Vancouver, Canada

|

| Nationality | Czechoslovak |

| Citizenship | British (1966), Canadian (1972) |

| Education |

|

| Occupation | Associate professor of pharmacology, University of British Columbia |

| Known for | Vrba–Wetzler report |

| Spouse(s) | Gerta Vrbová (m. 1947), Robin Vrba (m. 1975) |

| Children | 2 |

| Parent(s) | Elias Rosenberg, Helena Rosenberg (née Grünfeldová) |

| Awards |

|

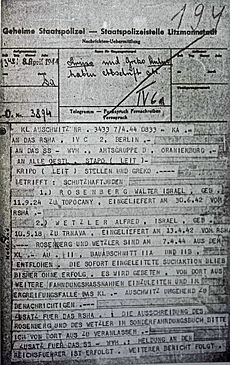

Rudolf "Rudi" Vrba (born Walter Rosenberg; 11 September 1924 – 27 March 2006) was a Slovak-Jewish biochemist. As a teenager in 1942, he was sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp in German-occupied Poland. He bravely escaped from the camp in April 1944. This was during the worst time of the Holocaust.

After his escape, he helped write a detailed report about the terrible killings happening at Auschwitz. This report was shared by George Mantello in Switzerland. Many believe it helped stop the mass deportation of Hungary's Jews to Auschwitz in July 1944. This action saved more than 200,000 lives. After the war, Vrba became a biochemist. He worked mostly in England and Canada.

Vrba and his fellow escapee Alfréd Wetzler fled Auschwitz. They escaped just three weeks after German forces invaded Hungary. This was also shortly before the SS began sending huge numbers of Hungarian Jews to the camp. The information they shared when they arrived in Slovakia on April 24, 1944, became known as the Vrba–Wetzler report. They explained that new arrivals in Auschwitz were being gassed. This was different from the German lie that people were being "resettled."

When the War Refugee Board finally published the report in November 1944, it shocked the world. The New York Herald Tribune called it "the most shocking document ever issued by a United States government agency." While other reports had given some information, the historian Miroslav Kárný said the Vrba–Wetzler report was special because of its "unflinching detail."

There was a delay of several weeks before the report was widely shared. Mass transports of Hungary's Jews to Auschwitz started on May 15, 1944. About 12,000 people were sent each day. Most of them went straight to the gas chambers. Vrba believed that if the report had been shared sooner, many people might have refused to board the trains. This could have stopped or slowed down the deportations.

From late June to July 1944, parts of the Vrba–Wetzler report appeared in newspapers and on radio in the United States and Europe. This was especially true in Switzerland. World leaders then asked Hungarian regent Miklós Horthy to stop the deportations. On July 2, American and British forces bombed Budapest. On July 6, Horthy ordered the deportations to end. By then, over 434,000 Jews had been sent away. This was almost all the Jewish people from the Hungarian countryside. But another 200,000 Jews in Budapest were saved.

Contents

Growing Up and Being Arrested

Rudolf Vrba was born Walter Rosenberg on September 11, 1924. He was born in Topoľčany, Czechoslovakia. This area is now part of Slovakia. He was one of four children. His mother's name was Helena Rosenberg, and his father was Elias. Vrba later changed his name to Rudolf Vrba after he escaped from Auschwitz.

His family owned a sawmill and lived in Trnava. In September 1941, the Slovak Republic was a state controlled by Nazi Germany. It passed a "Jewish Codex." This was like the Nuremberg Laws in Germany. It limited where Jews could live, go to school, and travel. Jews had to wear a yellow badge and live in specific areas.

When Vrba was 15, he was kicked out of high school in Bratislava because of these rules. He found work as a laborer. He continued to study at home, focusing on chemistry, English, and Russian. Around this time, he met his future wife, Gerta Sidonová. She had also been forced to leave school.

Vrba wrote that he got used to these rules. But he rebelled when the Slovak government announced in February 1942 that thousands of Jews would be sent to "reservations" in German-occupied Poland. Germany wanted these people for forced labor. The Slovak government paid Germany 500 RM for each Jew. They also claimed the deportees' property. Only about 800 of the 58,000 Slovakian Jews sent away between March and October 1942 survived.

Vrba decided he would not be "deported like a calf in a wagon." He planned to join the Czechoslovak Army in exile in England. At 17, he took a taxi to the border with a map and some money. He went to Budapest, Hungary. But he decided to return to Trnava. He was arrested at the Hungarian border. The Slovak authorities sent him to the Nováky transit camp. He escaped briefly but was caught again. An SS officer then ordered him to be sent on the next transport.

Life in the Camps

Majdanek Camp

On June 15, 1942, Vrba was sent from Czechoslovakia to the Majdanek concentration camp in Lublin, German-occupied Poland. There, he briefly saw his older brother, Sammy. They waved quickly; it was the last time he saw him. He also met "kapos" for the first time. These were prisoners chosen to help the guards. He recognized one kapo from Trnava.

Vrba's head and body were shaved. He was given a uniform, wooden shoes, and a cap. Prisoners had to remove their caps when SS guards were near. They were beaten for talking or moving slowly. Vrba worked as a builder's helper. When a kapo asked for 400 volunteers for farm work, Vrba signed up, hoping to escape. A Czech kapo who was friendly with Vrba hit him when he heard this. The kapo explained that the "farm work" was actually in Auschwitz.

Auschwitz I

On June 29, 1942, Vrba and other volunteers were moved to Auschwitz I. This was the main camp in Oświęcim. The journey took over two days. Vrba thought about escaping from the train. But the SS announced that ten men would be shot for every one who went missing.

In Auschwitz, Vrba had the number 44070 tattooed on his left arm. He was given a striped uniform and wooden shoes. After a long day of registration, he was taken to his barracks. It was an attic room near the main gate and the Arbeit macht frei sign.

Vrba was young and strong. A kapo named Frank "bought" him for a lemon. Lemons were valuable for their vitamin C. Vrba was assigned to work in the SS food store. This job gave him access to soap and water, which helped him survive. Frank, he learned, was a kind man. He would pretend to beat his prisoners when guards watched, but his blows always missed. The camp was otherwise very cruel.

Auschwitz II

"Kanada" Commando

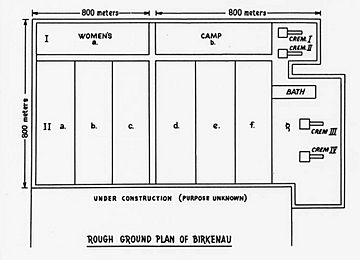

In August 1942, Vrba was moved to the Aufräumungskommando (clearing-up commando). This group was also called "Kanada." They worked in Auschwitz II-Birkenau. This was the extermination camp, about 2.5 miles from Auschwitz I. Many new arrivals brought kitchen tools and clothes for different seasons. This showed Vrba they believed the lies about being "resettled."

New arrivals who were strong enough were chosen for forced labor. The rest were taken by truck to the gas chambers. Vrba estimated that 90 percent were gassed. He told Claude Lanzmann in 1978 that the process was fast. It was designed to prevent panic, which would delay the next transport.

The new arrivals' belongings were taken to barracks called Effektenlager I and II. These were in Auschwitz I. Later, they were moved to Auschwitz II after Vrba escaped. Prisoners and even some camp staff called these barracks Kanada I and II. This was because they were full of goods. Everything was there: medicine, food, clothing, and cash. The "Kanada" commando repackaged most of it to be sent to Germany.

Vrba lived in Auschwitz I until January 15, 1943. Then he was moved to Auschwitz II. After about five months in Auschwitz, he got sick with typhus. He became very weak. At his worst, Josef Farber, a Slovakian resistance member, helped him. Farber brought him medicine and protected him.

In early 1943, Vrba became an assistant registrar in one of the blocks. He told Lanzmann that the resistance helped him get this job. It gave him access to important information. A few weeks later, in June, he became the main registrar (Blockschreiber) for block 10 in Auschwitz II. This was the quarantine section for men. This position gave him his own room and bed. He could also wear his own clothes. He was able to talk to new arrivals chosen for work. He also had to write reports, which let him ask questions and take notes.

Hungarian Jews Arrive

Vrba learned on January 15, 1944, that a new railway line was being built. It would lead directly to the crematoria. A kapo named Yup told him he had heard an SS officer say that a million Hungarian Jews would soon arrive. The old ramp could not handle so many people. A direct railway line would save thousands of truck trips from the old ramp.

Vrba had been planning to escape for two years. But now he was determined to act. He hoped to "undermine one of the principal foundations—the secrecy of the operation." A Soviet captain, Dmitri Volkkov, gave him advice. He said Vrba would need Russian tobacco soaked in petrol to fool the dogs. He also needed a watch for a compass, matches for food, and salt for nutrition. Vrba began studying the camp layouts. Both Auschwitz I and II had inner camps where prisoners slept. These were surrounded by a wide water trench and high-voltage barbed-wire fences. The area was lit at night and guarded by the SS. When a prisoner was missing, guards searched for three days and nights. To escape successfully, they needed to hide just outside the inner fence until the search ended.

His first escape plan was for January 26, 1944, with Charles Unglick. But it didn't work out. Unglick tried to escape alone and was killed.

Czech Family Camp

On March 6, 1944, Vrba heard that the Czech family camp was going to the gas chambers. About 5,000 people, including women and children, had arrived in Auschwitz in September 1943. They came from the Theresienstadt concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. Documents found later showed that the Germans set up this camp. It was a fake "model" camp for a planned Red Cross visit to Auschwitz. The group lived in relatively good conditions. But 1,000 people still died in six months.

The Escape

Vrba decided to escape again. In Auschwitz, he met Alfréd Wetzler (prisoner no. 29162). Wetzler was 26 and worked in the mortuary. He had arrived on April 13, 1942. Czesław Mordowicz, who escaped weeks after Vrba, said Wetzler planned their escape.

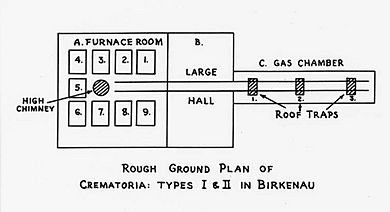

Wetzler wrote in his book Escape from Hell that the camp's underground resistance helped them. They provided information for Vrba and Wetzler to carry. A locksmith named "Otta" made a key for a shed. There, Vrba and others drew a camp map and dyed clothes. "Fero" from the central registry gave them data. "Filipek" (Filip Müller) added SS officers' names, a gas chamber plan, and records of transports. "Edek" smuggled out suits for them to wear. Other prisoners provided socks, shirts, a razor, a torch, and food.

Information about the camp, including a sketch of the crematorium, was hidden in two metal tubes. One tube was lost during the escape. The other held data about the transports. Vrba said they took no notes. He claimed they wrote the Vrba–Wetzler report from memory. He told historian John Conway he used "personal memory methods" to recall details. He said stories about written notes were made up because no one could explain his amazing memory.

Wearing suits, overcoats, and boots, they climbed into a hidden space. They had prepared it in a pile of wood. This was between Auschwitz-Birkenau's inner and outer fences. It was 2 PM on Friday, April 7, 1944, the eve of Passover. They sprinkled the area with tobacco soaked in gasoline. This was to keep dogs away, as advised by the Russian captain, Dmitri Volkov. Two Polish prisoners, Bolek and Adamek, moved the planks back into place.

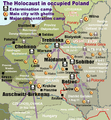

At 8:33 PM on April 7, the Birkenau commander learned two Jews were missing. On April 8, the Gestapo at Auschwitz sent telegrams with descriptions to other SS offices. The men hid in the wood pile for three nights and the fourth day. Wetzler wrote they lay there, soaking wet, counting the hours. On Sunday morning, April 9, Adamek whistled to signal it was safe. At 9 PM on April 10, they crawled out. Using a map from "Kanada," they headed south towards Slovakia, 130 km away. They walked along the Soła river.

The Vrba–Wetzler Report

Walking to Slovakia

Henryk Świebocki of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum said local Poles helped escapees. But Vrba wrote there was no organized help for them outside the camp. At first, they walked only at night. They ate bread from Auschwitz and drank from streams. On April 13, lost in Bielsko-Biala, they found a farmhouse. A Polish woman took them in for a day. She gave them bread, potato soup, and coffee. She explained that most of the area was "Germanized." Poles helping Jews risked death.

They kept following the river. Sometimes, a Polish woman would leave half a loaf of bread for them. On April 16, German gendarmes shot at them, but they escaped. Two other Poles helped them with food and shelter. Finally, they crossed the Polish–Slovakian border near Skalité on April 21, 1944. By then, Vrba's feet were so swollen he had cut off his boots. He was wearing carpet slippers given to him by a Polish peasant.

A peasant family in Skalité took them in for a few days. They fed and clothed them. Then, they connected them with a Jewish doctor in nearby Čadca, Dr. Pollack. Vrba and Pollack had met in a transit camp. Through a contact in the Slovak Jewish Council, Pollack arranged for people from Bratislava to meet the men. Pollack was very sad to learn what likely happened to his parents and siblings. They had been sent from Slovakia to Auschwitz in 1942.

Meeting the Jewish Council

Vrba and Wetzler stayed the night in Čadca. They were then taken to Žilina by train. Erwin Steiner, a member of the Slovak Jewish Council, met them. He took them to the Jewish Old People's Home, where the council had offices. Over the next few days, they met Ibolya Steiner, Oskar Krasniansky (an engineer), and Dr. Oskar Neumann, the council's leader.

The council confirmed who Vrba and Wetzler were using deportation lists. Wetzler wrote that the group had been waiting two years for someone to confirm the rumors about Auschwitz. Wetzler was surprised by their questions. The journalist wondered why the International Red Cross had not helped. Vrba became angrier as he spoke. The journalist asked for "specific cruelties by the SS men." Vrba replied: "That is as if you wanted me to tell you of a specific day when there was water in the Danube."

Vrba described the arrival ramp, the "selection" process, the Sonderkommando (special work units), and the camp's organization. He talked about the building of Auschwitz III. He explained how Jews were used as slave labor for big companies. He also described the gas chambers. Wetzler gave them the data from the central registry. He described the many deaths among Soviet prisoners of war. He also spoke about the destruction of the Czech family camp and medical experiments. He even handed over a label from a Zyklon B gas canister.

Neumann said they would get a typewriter in the morning. The group would meet again in three days. Hearing this, Vrba became very angry. "Easy for you to say 'in three days'!" he shouted. "But back there they are flinging people into the fire at this moment and in three days they'll kill thousands. Do something immediately!" He warned them all that they would end up in the gas chambers if nothing was done.

Writing the Report

The next day, Vrba started by sketching the layout of Auschwitz I and II. He also drew the position of the arrival ramp. The report was rewritten several times over three days. Wetzler wrote the first part, Vrba the third, and they worked on the second part together. Oskar Krasniansky translated it from Slovak into German as they wrote. Ibolya Steiner typed it up. The original Slovak version is now lost. The report was finished by Thursday, April 27, 1944.

According to Kárný, the report described the camp "with absolute accuracy." It included details about its construction, security, prisoner numbers, and living conditions. It also described the gassings, shootings, and injections. It gave details only prisoners would know. For example, discharge forms were filled out for gassed prisoners. This showed that death rates were faked. The report was clearly the work of many prisoners. It included sketches of the gas chambers. It stated there were four crematoria, each with a gas chamber and furnace. The report estimated the gas chambers could kill 6,000 people daily.

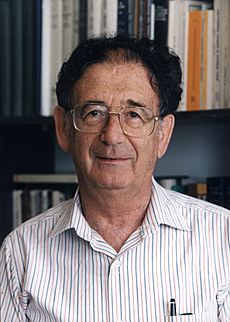

Vrba said he and Wetzler got information about the gas chambers from Sonderkommando Filip Müller. Müller and his colleagues worked there. Müller confirmed this in his book Eyewitness Auschwitz (1979). The Auschwitz expert Robert Jan van Pelt noted that the description had some errors. But he said this was normal given the circumstances. The men had no architectural training.

Sharing the News

Rosin and Mordowicz Escape

The Jewish Council found an apartment for Vrba and Wetzler in Liptovský Svätý Mikuláš, Slovakia. They kept a copy of the Vrba–Wetzler report there. It was in Slovak, hidden behind a picture. With help from a friend, Josef Weiss, they made secret copies. They gave them to Jews in Slovakia who had contacts in Hungary. These contacts translated the report into Hungarian.

According to historian Zoltán Tibori Szabó, the report was first published in Geneva in May 1944. It was in German, titled Tatsachenbericht über Auschwitz und Birkenau. Florian Manoliu of the Romanian Legation took the report to Switzerland. He gave it to George Mantello, a Jewish businessman. Mantello worked for the El Salvador consulate in Geneva. Thanks to Mantello, the report got its first wide coverage in the Swiss press.

Arnošt Rosin and Czesław Mordowicz escaped from Auschwitz on May 27, 1944. They arrived in Slovakia on June 6, the day of the Normandy landings. They heard about the invasion and thought the war was over. They celebrated using money they had smuggled out of Auschwitz. They were arrested for breaking currency laws. They spent eight days in prison until the Jewish Council paid their fines.

Rosin and Mordowicz were interviewed on June 17 by Oskar Krasniansky. He was the engineer who translated the Vrba–Wetzler report. They told him that between May 15 and 27, 1944, 100,000 Hungarian Jews had arrived at Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Most had been murdered upon arrival. Vrba concluded that the Hungarian Jewish Council had not told its Jewish communities about the Vrba–Wetzler report. The seven-page Rosin-Mordowicz report was combined with the Vrba–Wetzler report. A third report, the Polish Major's report, was also added. This combined document became known as the Auschwitz Protocols.

Mantello asked the Swiss-Hungarian Students' League to make 50 copies of the reports. By June 23, 1944, he had given them to the Swiss government and Jewish groups. Richard Lichtheim of the Jewish Agency in Geneva received a copy. Around June 19, he cabled the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem. He said they knew "what has happened and where it has happened." He also reported that 12,000 Jews were being sent from Budapest daily. He included the Vrba–Wetzler figure that 90 percent of Jews arriving at Auschwitz II were being murdered.

The Swiss students made thousands of copies. These were given to other students and politicians. At least 383 articles about Auschwitz appeared in the Swiss press between June 23 and July 11, 1944. This was more than all articles published about the Holocaust by British newspapers during the war.

The Importance of Dates

The dates when the report was shared became very important in Holocaust history. According to Randolph L. Braham, Jewish leaders were slow to share the report. They feared causing panic. Braham asked: "Why did the Jewish leaders in Hungary, Slovakia, Switzerland and elsewhere fail to distribute and publicize the Auschwitz Reports immediately after they had received copies in late April or early May 1944?" Vrba believed lives were lost because of this delay. He especially blamed Rudolf Kastner of the Budapest Aid and Rescue Committee. This committee had helped Jews escape to Hungary before the German invasion. The Slovakian Jewish Council gave Kastner the report by May 3, 1944, at the latest.

Reverend József Éliás, head of the Good Shepherd Mission in Hungary, said he got the report from Géza Soós. Soós was part of the Hungarian Independence Movement, a resistance group. Éliás's secretary, Mária Székely, translated it into Hungarian. She made six copies. These copies reached Hungarian and church officials. This included Miklós Horthy's daughter-in-law. Braham wrote that this happened before May 15.

Kastner's reasons for not sharing the report more widely are not fully known. Braham said, "Hungarian Jewish leaders were still busy translating and duplicating the Reports on June 14–16, and did not distribute them till the second half of June." Vrba argued that Rudolf Kastner held back the report. He believed Kastner did not want to risk talks between his committee and Adolf Eichmann. Eichmann was the SS officer in charge of sending Jews out of Hungary. As the Vrba–Wetzler report was being written, Eichmann had offered the Committee a deal. He proposed trading up to one million Hungarian Jews for 10,000 trucks and other goods from the Western Allies. This deal failed. But Kastner collected money to pay the SS. This allowed over 1,600 Jews to leave Budapest for Switzerland on the Kastner train. Vrba believed Kastner kept the report secret to avoid upsetting the SS.

The Hungarian biologist George Klein worked as a secretary for the Hungarian Jewish Council in Budapest. In late May or early June 1944, his boss showed him a copy of the Vrba–Wetzler report in Hungarian. He was told to tell only close family and friends. Klein had heard of "extermination camps," but it seemed like a myth. "I immediately believed the report because it made sense," he wrote in 2011. "The dry, factual, nearly scientific language, the dates, the numbers, the maps and the logic of the narrative coalesced into a solid and inexorable structure." Klein told his uncle, who asked how Klein could believe such nonsense. It was the same with other relatives and friends. Older men with property and family did not believe it. But younger people wanted to act. In October that year, when it was time for Klein to board a train to Auschwitz, he ran away instead.

Meetings with Important People

The Slovakian Jewish Council asked Vrba and Czesław Mordowicz to meet with Monsignor Mario Martilotti. He was a Vatican representative. They met at the Svätý Jur monastery on June 20, 1944. Martilotti had seen the report. He questioned the men for five hours. Mordowicz was annoyed by Vrba during this meeting. He said Vrba, then 19, acted cynically. At one point, he seemed to make fun of Martilotti cutting his cigar. Mordowicz worried this behavior would make their information seem less believable. To keep Martilotti's attention, he told him that Catholics and priests were being murdered with the Jews. Martilotti reportedly fainted, shouting "Mein Gott! Mein Gott!" Five days later, Pope Pius XII sent a telegram to Miklós Horthy.

Vrba and Mordowicz also met Michael Dov Weissmandl. He was an Orthodox rabbi and a leader of the Bratislava Working Group. They met at his yeshiva in Bratislava. Vrba wrote that Weissmandl was well informed and had seen the Vrba–Wetzler report. He had also seen the Polish major's report about Auschwitz. Weissmandl asked what could be done. Vrba explained: "The only thing to do is to explain... that they should not board the trains..." He also suggested bombing the railway lines into Birkenau. (Weissmandl had already suggested this on May 16, 1944.)

Deportations Halted

Many appeals were made to Horthy. These came from the Spanish, Swiss, and Turkish governments. Also, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Gustaf V of Sweden, and the International Committee of the Red Cross appealed. On June 25, 1944, Pope Pius XII sent a telegram. The Pope's telegram did not mention Jews. It asked that "the sufferings... endured by a large number of unfortunate people, because of their nationality or race, may not be extended and aggravated."

John Clifford Norton, a British diplomat, suggested bombing government buildings in Budapest. On July 2, American and British forces did bomb Budapest. They killed 500 people and dropped leaflets. These warned that those responsible for deportations would be held accountable. Horthy ordered an end to the mass deportations on July 6. This was because he was "deeply impressed by Allied successes in Normandy." He also wanted to show his power over the Germans. He feared a pro-German takeover.

After the Report

Resistance Activities

After telling his story in April 1944, Vrba and Wetzler stayed in Liptovský Mikuláš for six weeks. They continued to make and share copies of the report. A friend, Joseph Weiss, helped them. The Jewish Council gave Vrba new papers under the name Rudolf Vrba. These papers falsely showed he had Aryan ancestors. They also gave him money to live secretly in Bratislava. On August 29, 1944, the Slovak Army rebelled against the Nazis. Czechoslovakia was announced to be re-established. Vrba joined the Slovak partisans in September 1944. He later received the Czechoslovak Medal of Bravery.

Auschwitz was freed by the 60th Army of the Red Army on January 27, 1945. They found 1,200 prisoners in the main camp and 5,800 in Birkenau. The SS had tried to destroy the evidence. But the Red Army found what was left of four crematoria. They also found thousands of shoes, suits, and other clothing items. They found carpets, toothbrushes, eyeglasses, dentures, and seven tons of human hair.

Marriage and Education

In 1945, Vrba met his childhood friend, Gerta Sidonová. They both wanted to go to college. They took special courses for those whose schooling was interrupted by the Nazis. They moved to Prague and married in 1947. Gerta took the name Vrbová. She studied medicine and later did research. In 1949, Vrba earned a chemistry degree from the Czech Technical University in Prague. He received a scholarship. In 1951, he got his doctorate for a thesis on "the metabolism of butyric acid." The couple had two daughters: Helena (1952–1982) and Zuzana (born 1954). Vrba continued his research at the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. He received another degree in 1956. From 1953 to 1958, he worked for Charles University Medical School in Prague. His marriage ended around this time.

Moving to Israel and England

After his marriage ended, Vrba and Vrbová both left Czechoslovakia. He went to Israel, and she went to England with their children. Vrbová had fallen in love with an Englishman. She was able to leave after being invited to a conference in Poland. She couldn't get visas for her children. So, she returned illegally to Czechoslovakia. She walked her children over the mountains to Poland. From there, they flew to Denmark with fake papers, then to London.

In 1957, Vrba read Gerald Reitlinger's book The Final Solution. He learned that the Vrba–Wetzler report had been shared and saved lives. He had heard rumors about this around 1951, but the book confirmed it. The next year, he was invited to a conference in Israel. While there, he decided to stay. For two years, he worked at the Weizmann Institute of Science. He later said he couldn't stay in Israel. He felt that the same people who had, in his opinion, betrayed the Jewish community in Hungary were now in power there. In 1960, he moved to England. He worked in research for nine years. He became a British subject on August 4, 1966.

Sharing His Story

Trial of Adolf Eichmann

Adolf Eichmann was captured in Buenos Aires on May 11, 1960. He was taken to Jerusalem for his trial. Vrba was not asked to testify at first. The Israeli Attorney General wanted to save money. Since Auschwitz was in the news, Vrba contacted the Daily Herald in London. A reporter, Alan Bestic, wrote his story. It was published in five parts starting February 27, 1961. The headline was "I Warned the World of Eichmann's Murders." In July 1961, Vrba sent a sworn statement to the Israeli Embassy in London.

Trial of Robert Mulka and Book

Vrba testified against Robert Mulka of the SS at the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials. He told the court he had seen Mulka at the Judenrampe (Jewish ramp) at Auschwitz-Birkenau. The court found Vrba to be "excellent and intelligent." They said he would have been very observant because he was planning his escape. The court ruled that Mulka had been on the ramp. Mulka was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

After the newspaper articles, Bestic helped Vrba write his memoir, I Cannot Forgive (1963). It was also published as Factory of Death (1964). The book was later republished in English in 1989 and 2002.

Moving to Canada and Interview

Vrba moved to Canada in 1967. He worked for the Medical Research Council of Canada until 1973. He became a Canadian citizen in 1972. From 1973 to 1975, he was a research fellow at Harvard Medical School. There, he met his second wife, Robin Vrba. They married in 1975 and moved back to Vancouver. She became a real-estate agent. He became an associate professor of pharmacology at the University of British Columbia. He worked there until the early 1990s. He published over 50 research papers on brain chemistry, diabetes, and cancer.

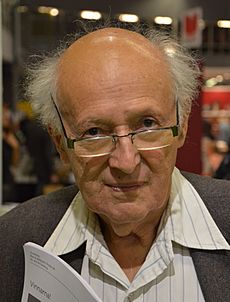

Claude Lanzmann interviewed Vrba in November 1978 in New York. This was for Lanzmann's long documentary about the Holocaust, Shoah (1985). The interview can be found on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The film was first shown in October 1985.

Trial of Ernst Zündel

In January 1985, Vrba testified in Toronto. This was at the trial of Holocaust denier Ernst Zündel. Zündel's lawyer tried to make Vrba (and other survivors) seem unreliable. He asked for very detailed descriptions. Then he pointed out any small difference as important.

The lawyer argued that Vrba's knowledge of the gas chambers was secondhand. Vrba's statement for Adolf Eichmann's trial in 1961 said he got information from Sonderkommando Filip Müller. Müller confirmed this in 1979. The lawyer asked if Vrba had seen anyone gassed. Vrba replied that he saw people taken into the buildings. He also saw SS officers throw gas canisters in after them. "Therefore, I concluded it was not a kitchen or a bakery, but it was a gas chamber," he said. The trial ended with Zündel being found guilty of publishing false material about the Holocaust.

Meeting with George Klein

In 1987, the Swedish–Hungarian biochemist George Klein traveled to Vancouver to thank Vrba. Klein had read the Vrba–Wetzler report in 1944 as a teenager in Budapest. He escaped because of it. He wrote about their meeting in his book Pietà (1992). Klein said the traveler's biggest fear was seeing Hell but not being believed.

Klein had seen Vrba's interview in Shoah in 1985. He disagreed with Vrba's claims about Kastner. Klein had seen Kastner working in the Jewish Council offices in Budapest. He viewed Kastner as a hero. He told Vrba how he had tried to convince others in Budapest about the report's truth. But no one believed him. This made him think Vrba was wrong to say Jews would have acted if they had known. Vrba said Klein's experience proved his point. Sharing the report informally did not give it authority.

Klein asked Vrba how he could work at the University of British Columbia. No one there understood what he had been through. Vrba told him about a colleague who saw him in Lanzmann's film. The colleague asked if the film was true. Vrba replied: "I do not know. I was only an actor reciting my lines." The colleague said, "How strange. I didn't know that you were an actor."

Death

Vrba's fellow escapee, Alfréd Wetzler, died in Bratislava, Slovakia, on February 8, 1988. Wetzler wrote Escape From Hell: The True Story of the Auschwitz Protocol (2007).

Vrba died of cancer at age 81 on March 27, 2006, in Vancouver. He was survived by his first wife, Gerta Vrbová, and his second wife, Robin Vrba. He also left behind his daughter, Zuza Vrbová Jackson, and his grandchildren, Hannah and Jan. His elder daughter, Dr. Helena Vrbová, died in 1982 during a malaria research project. Robin Vrba gave Vrba's papers to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in New York.

Vrba's Views and Criticisms

The Gruenwald Trial

It bothered Vrba for the rest of his life that the Vrba–Wetzler report was not widely shared until June–July 1944. This was weeks after his escape in April. Between May 15 and July 7, 1944, 437,000 Hungarian Jews were sent to Auschwitz. In his view, these people boarded the trains believing they were going to a Jewish reservation.

Vrba argued that if the deportees had known the truth, they would have fought or run. Or at least, panic would have slowed the transports. He claimed that Rudolf Kastner of the Budapest Aid and Rescue Committee held back the report. Kastner had a copy by May 3, 1944. Vrba believed Kastner did this to protect talks with Adolf Eichmann and other SS officers. These talks were about exchanging Jews for money and goods. Vrba argued that the SS was just pretending to negotiate. They wanted to keep Jewish leaders calm and prevent rebellion.

In I Cannot Forgive (1963), Vrba mentioned the 1954 trial in Jerusalem of Malchiel Gruenwald. Gruenwald was a Hungarian Jew living in Israel. In 1952, Gruenwald accused Rudolf Kastner of working with the SS. He claimed Kastner did this so he could escape Hungary with a few chosen people, including his family. Kastner had bribed the SS to let over 1,600 Jews leave Hungary for Switzerland on the Kastner train in June 1944. He had also testified for leading SS officers at the Nuremberg trials.

Vrba agreed with Gruenwald's criticism of Kastner. The Israeli government sued Gruenwald for libel on Kastner's behalf. In June 1955, Judge Benjamin Halevi mostly sided with Gruenwald. He ruled that Kastner had "sold his soul to the devil." The judge said that many Jews boarded the trains "ignorant of the real destination." He said they trusted the false claim that they were being sent to work camps. The Kastner train, the judge said, was a payoff. Protecting certain Jews was part of the SS's plan to destroy the Jews. Kastner was assassinated in Tel Aviv in March 1957. The verdict was partly overturned by the Supreme Court of Israel in 1958.

Criticism of Jewish Councils

Vrba blamed Kastner and the Hungarian Aid and Rescue Committee for not sharing the Vrba–Wetzler report. He also criticized the Slovakian Jewish Council. He said they failed to resist the deportation of Jews from Slovakia in 1942. When he was sent to the Majdanek concentration camp that year, he claimed the Jewish Council knew Jews were being murdered in Poland. But they did nothing to warn the community. He even said they helped by making lists of names. He called Jewish leaders in Slovakia and Hungary "quislings" (traitors). He believed they were essential for the deportations to run smoothly.

The Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer argued that the Council knew Jews were in danger. But he said they didn't know about the Final Solution at that time. Bauer wrote that some Jewish Council members did work with the SS. They helped make lists of Jews to be deported. But other members warned Jews to flee. They later formed a resistance group, the Working Group. This group took over the Jewish Council in December 1943. Vrba did not accept Bauer's differences.

Responses to Vrba's Views

Vrba's idea that Jewish leaders betrayed their communities was supported by historian John S. Conway. Conway was a colleague of Vrba's. He wrote papers defending Vrba's views. In 1996, Vrba repeated his claims in a German article. Yehuda Bauer responded to this article in 1997. Bauer also responded to Conway in 2006.

Bauer believed Vrba's "wild attacks on Kastner and on the Slovak underground are all a-historical and simply wrong." But he admitted that many survivors shared Vrba's view. Bauer argued that by the time the Vrba–Wetzler report was ready, it was too late to change the Nazis' plans. He thought Hungarian Jews knew about the mass murder, even if they didn't know all the details. He also believed they would have been forced onto the trains anyway, even if they had seen the report. Vrba claimed Bauer was one of the Israeli historians who downplayed Vrba's importance. He said they did this to protect the Israeli establishment.

The British historian Michael Fleming argued in 2014 that Hungarian Jews did not have enough information. After the German invasion of Hungary in March 1944, the BBC warned the Hungarian government that "racial persecution will be regarded as a war crime." But on April 13, the BBC decided not to broadcast warnings directly to Hungarian Jews. They thought it would "cause unnecessary alarm." They also believed Jews "must in any case be only too well-informed." Fleming wrote that this was a mistake. The Germans had tricked the Jewish community into thinking they were being sent to Poland to work. The first time extermination camps were mentioned in BBC warnings to Hungary was June 8, 1944.

Randolph L. Braham, an expert on the Holocaust in Hungary, agreed that Hungarian Jewish leaders did not keep their communities informed. He said they did not take "any meaningful precautionary measures." He called this "one of the great tragedies of the era." However, he also said that by the time the Vrba–Wetzler report was available, the Jews of Hungary were helpless. They were "marked, hermetically isolated, and expropriated." There was nothing they could have done to resist, he wrote, even if they had known about the report.

In 2001, a group of Israeli activists and historians criticized Vrba. They published articles in Hebrew. They said Vrba's claims that the Bratislava Working Group worked with the SS were "baseless." They said these claims ignored the difficult conditions Jews faced. Vrba was called "the head of these mockers," but his heroism was "beyond doubt."

Vrba's Place in History

Vrba felt that Israeli historians tried to remove his name from Holocaust history. He believed this was because of his views on Kastner and the Jewish Councils. Some of these people later held important positions in Israel. When Ruth Linn first tried to visit Vrba, he reportedly "chased her out of his office." He said he had no interest in "your state of the Judenrats and Kastners."

Linn wrote in her book Escaping Auschwitz: A Culture of Forgetting (2004) that Vrba's and Wetzler's names were left out of Hebrew textbooks. Or their contribution was made to seem small. Standard histories referred to the escape by "two young Slovak Jews" or "two chaps." They were presented as messengers of the Polish underground. Dr. Oskar Neumann of the Slovak Jewish Council called them "these chaps" in his memoir. Oskar Krasniansky, who translated the report, only mentioned them as "two young people." There was also a tendency to call the Vrba–Wetzler report the Auschwitz Protocols. This is a combination of the Vrba–Wetzler and two other reports. The 1990 edition of the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust named Vrba and Wetzler. But in the 2001 edition, they were "two Jewish prisoners."

Vrba's memoir was not translated into Hebrew until 1998. This was 35 years after it was published in English. As of that year, there was no English or Hebrew version of the Vrba–Wetzler report at Yad Vashem. This is the Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem. The museum blamed a lack of money. There was a Hungarian translation. But it did not name the authors. Linn wrote it could only be found in a file about Rudolf Kastner. Linn herself, born and raised in Israel, first learned about Vrba from Claude Lanzmann's film Shoah (1985). In 1998, she surveyed 594 university students. 98 percent said no one had ever escaped from Auschwitz. The rest did not know the escapees' names. This failure to recognize Vrba has helped Holocaust deniers. They have tried to question his testimony about the gas chambers.

In 2005, Uri Dromi of the Israel Democracy Institute responded. He said there were at least four Israeli books on the Holocaust that mentioned Vrba. He also said Wetzler's story was told in detail in Livia Rothkirchen's book, published in 1961.

Images for kids

-

Vrba at school (front row, fourth left), Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, 1935–1936

-

Gestapo telegram reporting the escape, 8 April 1944

-

Concentration camps in occupied Europe (Auschwitz ringed), 2007 borders; same map with WWII borders

-

Hungarian Regent Miklós Horthy ordered an end to the deportations on 6 July 1944.

-

Malchiel Gruenwald (front, waving), Supreme Court of Israel, 22 June 1955)

See also

In Spanish: Rudolf Vrba para niños

In Spanish: Rudolf Vrba para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |