Sabin Manuilă facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sabin Manuilă

|

|

|---|---|

Manuilă in 1934

|

|

| Born | February 19, 1894 Sâmbăteni, Arad County, Austria-Hungary

|

| Died | November 20, 1964 (aged 70) |

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

Sabin Manuilă (February 19, 1894 – November 20, 1964) was a Romanian statistician, demographer, and doctor. He was born in Austria-Hungary but became a key figure in Romania. Manuilă was known for his early studies on population statistics in Transylvania and Banat. He also promoted ideas about improving human populations, known as eugenics, and how governments could influence society.

As a specialist in how population and geography affect politics, Manuilă supported ways to strengthen Greater Romania. This included ideas like exchanging populations, encouraging people to move to certain areas, and policies that sometimes discriminated against certain groups. He became involved in national politics in the 1930s. He led Romania's first Statistical Institute. During World War II, he advised Romanian leader Ion Antonescu. Manuilă supported laws that discriminated against Jewish people and Romani people. He was one of the first to suggest moving Romanian Jews and Romani people to an area called Transnistria. He also played a role in discussions between Romania and Hungary about the region of Northern Transylvania.

By 1944, Manuilă opposed Antonescu. He was involved in the coup that removed Antonescu from power. He stayed active in politics even after the Soviets occupied Romania. He served in two governments. However, he later disagreed with the Romanian Communist Party. He left Romania before the communist government fully took control. He then joined the Romanian National Committee abroad. He spent his last years in the United States, working for Stanford University and the Census Bureau.

Contents

Early Life and Beginnings

Growing Up in Transylvania

Sabin Manuilă was born in Sâmbăteni, Arad County. This area was on the border between the Banat and Crișana regions, which were part of Austria-Hungary at the time. His father, Fabriciu Manuilă, was a Romanian Orthodox priest. Father Fabriciu was an activist who fought against the Hungarian government's efforts to make Romanians speak Hungarian. Sabin's uncle, Vasile Goldiș, was also a well-known Romanian activist.

The Manuilă family held some prejudiced views against Romani people. This might have influenced Sabin's later political ideas. Sabin was educated at home and then finished high school in Brașov. He couldn't study in Romanian, so he went to medical school at Budapest University in 1912. He continued to be active in Romanian nationalist groups and wrote articles for political newspapers.

World War I and Union with Romania

Manuilă paused his studies from 1914 to 1918 to fight in World War I. He served as a medic in the Austro-Hungarian Army on the Russian Front and was wounded.

By November 1918, after Austria-Hungary broke apart, Manuilă was working as a doctor in Lipova. He rejoined nationalist activities to support the union of Crișana and Transylvania with Romania. He became a local commander in the Romanian National Guard. In December, his university friends asked him to represent them at the Alba Iulia grand national assembly. There, he voted for union with Romania. His uncle, Goldiș, read the motion for union. His father and brother were also there. In 1919, he earned his doctorate in medicine. In 1920, he married Veturia Leucuția, who also became a doctor. She helped create nursing education in Romania.

Early Scientific Career

Manuilă soon started working at Cluj University. He first led the children's hospital and then the social hygiene department. His scientific career grew quickly between 1919 and 1926. He collected many blood samples in Transylvania. This was new research in serology (study of blood serum) and immunology (study of the immune system). He published his findings in international science journals.

He also wrote about epidemiology (study of diseases) and how to organize the healthcare system. His book Epidemics in Transylvania won an Academy Prize in 1921. This project also looked into "racial science." Manuilă studied ideas about "racial index" and thought Romanians were a distinct group among Balkan peoples. Other scientists debated his findings.

Manuilă became an assistant to Iuliu Moldovan, a leader in Romanian public health and a supporter of eugenics. Manuilă received a Rockefeller Scholarship. He studied biostatistics (using statistics in biology) at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore from 1925 to 1926. He visited Charles Davenport's lab and became convinced that American eugenics could work in Romania. His wife, Veturia, also a Rockefeller scholar, joined him. She became interested in social work and later became a conservative feminist.

National Role and Controversial Policies

Leading the Census

After returning to Romania, Manuilă became a public health inspector in Transylvania. In 1927, he gave lectures on eugenics and biopolitics (how government policies affect populations). He started a research center at Cluj University, working with other eugenicists.

In 1927, Manuilă moved to Bucharest. He worked with Dimitrie Gusti, a sociologist, and other statisticians. He focused on studying Romania's population and its history. He was one of the first Romanians to predict future population changes. According to statistician Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, Manuilă's work on Romania's population statistics was "an international paragon."

In 1929, he joined Gusti's Romanian Social Institute. He helped lead the nationwide census of 1930, supported by the Rockefeller Foundation. He then led the Institute of Demography and Census. At the Social Institute, he created a section for eugenics and biological anthropology. Manuilă and his wife also started a School of Social Work in Bucharest. This school also promoted eugenic ideas.

Manuilă made important discoveries about the population of Transylvania. He studied how cities became more Romanian. In 1929, his book The Demographic Evolution of Cities and Ethnic Minorities in Transylvania won another Academy prize. He proposed ideas for population exchanges between Greater Romania and its neighbors. The goal was to remove "elements with a centrifugal tendency" (groups that might pull away from Romania) and keep "ethnic purity." He even suggested moving Romanians from Hungary to his home region of Crișana. Manuilă also pushed for social welfare laws that he believed would stop Romanians from leaving the country and help build a Romanian urban society. He thought that Romanianization was a natural process as more Romanians moved to cities.

Political Involvement and World War II

Manuilă was politically active and joined the National Peasants' Party. From 1927 to 1930, he was a high-ranking official in the Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Protection. He served as Undersecretary of State under Prime Minister Iuliu Maniu. He later became Maniu's adviser on social issues. He represented Romania at international statistical and sociological conferences. He supported ideas that promoted high birth rates and racial theories.

In 1933, Nazi Germany brought racism into focus. In 1934, Manuilă expressed some concerns about Nazi racial ideas. He believed in "racial determinism" but thought Nazi "racial science" was "young" and "compromising" the racial agenda. He also said that Romanian Jews were "not a racial, but an economic problem." In 1935, he was Vice President of a conference in Berlin that promoted Nazi biopolitics. By the end of the 1930s, Manuilă became concerned about miscegenation (interracial marriage).

In 1938, Manuilă became head of the Central Statistical Institute (ICS). His new research produced detailed books, including a 1937 study on The Population of Romania. He also contributed to a 1938 Romanian encyclopedia, which analyzed the 1930 census data. During the Great Depression, he wrote about "overpopulation" in universities causing unemployment. He suggested the government should select human capital.

Wartime Policies and Deportations

Manuilă's career changed during the early years of World War II. His focus shifted to geopolitics (how geography affects politics) and historical geography. In 1938, he became a member of the Romanian Academy. In 1939, the government closed his ICS, leaving statisticians unemployed. However, in 1940, the government again used Manuilă's expertise. Romania was aligning with Nazi Germany. This meant negotiating land exchanges with Hungary. Manuilă attended meetings where population exchanges were first considered.

Eventually, the Second Vienna Award gave Northern Transylvania to Hungary. Manuilă was present at these discussions. The ICS became important again in late 1940. After the Vienna Award, Romania was led by Ion Antonescu. Manuilă and his staff worked directly for Antonescu. They provided information for government decisions and made population plans for a future peace. Historian Viorel Achim noted that Antonescu often consulted Manuilă on population policy.

Historian Vladimir Solonari states that Antonescu trusted Manuilă's expertise. Manuilă became a strong supporter of Nazi racial policies, which he wanted to bring to Romania. The ICS became the main tool for "ethnopolitics" (policies based on ethnic groups). Manuilă connected Antonescu with Nazi racial scientists.

Manuilă supported laws that separated Jewish people from others. He believed that Jewish wealth and influence needed to be controlled. However, his views on Jewish people were more complex than the extreme views of some groups. In 1940, he suggested creating a "Superior Council for the Protection of the Race." He wrote that Jewish people were mostly harmless and kept to themselves. He argued that Romania's "racial issue" was with Romani people, whom he described as "dysgenic" (having undesirable traits) and disruptive. His ideas were supported by German scientists.

Manuilă began a new census, a very complex operation. It was meant to support Romania's claims on its neighbors. The 1941 census included a special section to list all Jewish property. Manuilă also advised the government to add the criminal records of Romani individuals to census data.

Deportations to Transnistria

In late 1941, as Romania fought alongside Germany, Manuilă again suggested population exchanges to solve the Northern Transylvania issue. He discussed this with Antonescu. Manuilă also imagined moving ethnic Romanians from Bulgaria and Serbia back to Romania. He also thought about moving all Germans in Romania to Germany. He advised Antonescu on moving scattered Romanian Ukrainians to Transnistria. These groups were then to be moved to other areas to replace Jewish people, Ukrainians, and Russian Bessarabians. This plan was put into action in November 1941.

Manuilă's papers also suggested deporting all Romanian Jews and Romani people to Transnistria. He saw them as people without a country or outside protection. This measure was meant to make Romania "ethnically homogeneous." While it was influenced by eugenics, it did not call for their physical elimination.

Manuilă's wife, Veturia, worked with Antonescu's wife, Maria, on a state charity. This charity was involved in taking money from Jews who were being deported. In 1942, Manuilă's inspections in Transnistria made him aware of the 1941 Odessa massacre and death marches. Later that year, Manuilă was asked to study Romanian soldiers to find evidence of Jewish intermarriage. In 1943, Antonescu assigned Manuilă to a government group for "Promoting and Protecting the Biological Capital of the Nation."

Historian Achim notes that Manuilă's population-exchange texts do not show a racist agenda. However, they were in line with Antonescu's policies of ethnic cleansing. One memo officially claimed a "Gypsy problem," describing Romani people as a "dysgenic" threat. He also believed Romani people were undercounted in the 1930 census. Historians Dennis Deletant and M. Benjamin Thorne note that Manuilă's eugenic ideas about Romani people influenced Antonescu's policies, leading to their deportation.

Later Years and Legacy

The 1944 Coup and Aftermath

Despite his official roles, Manuilă was still connected to the National Peasants' Party, which secretly opposed Antonescu. Some believed Manuilă was spying for the Americans. Achim noted that Manuilă was seen as a democrat by many, despite his views on minorities. At the ICS, he protected some 5,000 Jewish people by employing them, preventing their deportation. This was against his usual policies.

The ICS also secretly hosted a cell of the Romanian Communist Party. This group played a big part in the anti-fascist coup of August 1944. Manuilă helped with communications between the Communist Party and Maniu. After the Soviets occupied Romania, Manuilă joined the Romanian Society for Friendship with the Soviet Union. He also wrote that America's victory in the war showed its better health policies.

Manuilă was publicly praised by the Jewish community for helping to save some Jewish people. He tried to hide his earlier role in creating anti-Jewish laws. In a 1944 interview, he said that racial laws were a "great aberration" and "alien to the traditions of the Romanian nation."

Manuilă joined a party allied with the communists. In November, he became Undersecretary of State. Romania then joined the Allies and fought against Hungary in Northern Transylvania. Manuilă worked to return Romanian administrators to the area. He also campaigned internationally for Romania's rule in Northern Transylvania. He cited population and historical evidence in his English book, The Vienna Award and Its Demographical Consequences (1945).

Leaving Romania

Manuilă kept his government job for a short time but was forced out by the communists in March 1945. He returned to the ICS but faced conflicts with the communist party. He lost his other positions and was demoted at the Institute in August 1947. He became a political suspect, not for his Nazi contacts, but because he was seen as pro-American.

Manuilă planned to escape Romania by plane, but it was stopped by police. He then used a people-smuggling operation to cross the border into Hungary. Sabin and Veturia Manuilă eventually made their way to the United States.

In 1948, Manuilă settled in New York City. He continued his scientific work and was active in the Romanian exile community. He worked with various organizations, including the Romanian National Committee (RNC). He also led a section on the Study of Displaced Populations. His wife, Veturia, also joined exile groups and spoke on Radio Free Europe. In 1952, Manuilă became an RNC representative to the United Nations.

Later Life and Studies

In 1950, Manuilă debated with American broadcaster George Sokolsky. Sokolsky suggested Romania deserved its fate because it had a fascist government. Manuilă replied that Romania had overthrown its fascist government, unlike other countries that received American aid.

Professionally, Manuilă worked at Stanford University and then as a Counselor for the United States Census Bureau. He dealt with social security, population trends, and refugee integration. In the 1950s, he also completed studies on the population history of Romanian Jews. He worked with Wilhelm Filderman, a Jewish Romanian activist in exile, who helped him get data. Manuilă presented his findings at a conference in Stockholm in 1957. However, according to historian Jean Ancel, Manuilă used Filderman's help to downplay Romania's role in the Holocaust.

In September 1963, Manuilă attended a sociology conference in Córdoba, Argentina. He presented a paper on wartime population changes in Romania. He died in New York City on November 20, 1964. His wife, Veturia, continued to publish her work.

Manuilă's membership in the Romanian Academy was taken away during communist rule. He was given it back in July 1990, after the Romanian Revolution. Access to his archives was restricted for a long time.

Historian Maria Bucur notes that later descriptions of Manuilă often portray him as a "tolerant, rational, balanced" scientist. These descriptions sometimes overlook his actions during the war. In the 1990s, Manuilă's studies on minority populations were used by some who denied the Holocaust. This was an attempt to create doubt about Antonescu's crimes against Jewish people.

Images for kids

-

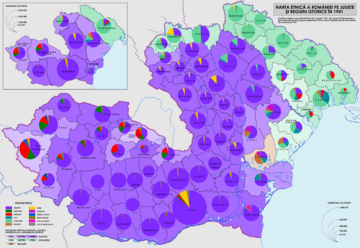

Map of the results of the 1941 census, with counties sorted by ethnicity. Romanians in purple, Ukrainians in light green (concentrated in Transnistria, Bukovina and the Budjak), with Jews in yellow, Germans in red, and Hungarians in dark green. Romanies shown as slivers of light brown, with higher concentrations in Bucharest and Oltenia

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |