Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

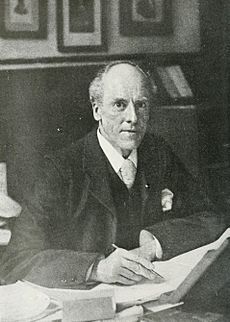

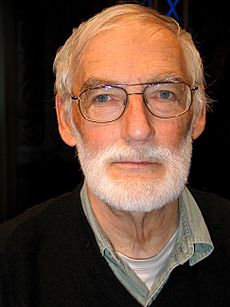

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen

|

|

|---|---|

| Nicolae Georgescu | |

| Born | February 4, 1906 Constanța, Romania

|

| Died | October 30, 1994 (aged 88) Nashville, Tennessee, United States

|

| Resting place | Bellu Cemetery, Bucharest |

| Alma mater | University of Bucharest, Paris Institute of Statistics, University College London |

| Known for | Utility theory, consumer choice theory, production theory, biophysical economics, ecological economics |

| Spouse(s) | Otilia Busuioc |

| Awards | The Harvie Branscomb Award |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Economics, mathematics, statistics |

| Institutions | University of Bucharest (1932–46), Harvard University (1934–36), Vanderbilt University (1950–76), Graduate Institute of International Studies (1974), University of Strasbourg (1977–78) |

| Academic advisors | Traian Lalescu, Émile Borel, Karl Pearson, Joseph Schumpeter |

| Doctoral students | Herman Daly |

| Other notable students | Muhammad Yunus |

| Influences | Aristotle, Rudolf Clausius, Ernst Mach, Maurice Allais |

| Influenced | Herman Daly, Jeremy Rifkin, Cutler J. Cleveland, John M. Gowdy, André Gorz, Joan Martinez Alier, Jacques Grinevald, Serge Latouche, Malte Michael Faber, Stefano Zamagni, Mauro Bonaiuti |

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (born Nicolae Georgescu, 4 February 1906 – 30 October 1994) was a smart Romanian mathematician, statistician, and economist. He is famous for his 1971 book, The Entropy Law and the Economic Process. In this book, he explained that all natural resources are used up and changed forever when we use them in our economy.

Georgescu-Roegen's ideas were very important for starting a new field called ecological economics. This area of study looks at how the economy and nature are connected. Many experts believe he was ahead of his time.

He was the first economist to really think about how all of Earth's mineral resources will eventually run out. He argued that our planet's ability to support human life and consumption (called its carrying capacity) will decrease. This is because we keep using up Earth's limited mineral resources. He believed this could lead to a future collapse of the world economy and even human extinction. Because of his serious and somewhat sad view, his ideas were called 'entropy pessimism'.

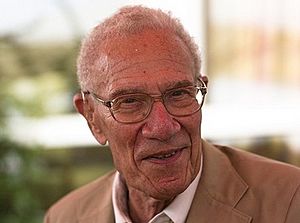

Early in his career, Georgescu-Roegen was a student of Joseph Schumpeter, a famous economist. Later, Georgescu-Roegen taught Herman Daly, who then developed the idea of a steady-state economy. This idea suggests that governments should limit how many natural resources we use.

Georgescu-Roegen's work helped create ecological economics in the 1980s. He also greatly influenced the degrowth movement in France and Italy. This means he taught and inspired many people over several generations.

Many mainstream economists found his work difficult because it sounded more like applied physics than traditional economics. Also, some of his ideas about thermodynamics had small errors, which caused some debate among scientists.

Contents

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen: His Life Story

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen lived for most of the 20th century, from 1906 to 1994. He saw two world wars and three dictatorships in his home country, Romania, before he had to leave. Later, living in the US, he watched as socialism rose and fell in Romania.

He made many important contributions to economics before he wrote his big book, The Entropy Law and the Economic Process. Even though this book helped start ecological economics, Georgescu-Roegen was sad that his ideas didn't get more attention during his lifetime.

Early Life and Schooling

Nicolae Georgescu was born in Constanța, Romania, in 1906. His family was not rich. His father, who was an army officer, taught him to read, write, and count. His mother, a sewing teacher, showed him the value of hard work. His father died when Nicolae was only eight years old.

Constanța was a small port city on the Black Sea. The mix of different cultures there helped Nicolae become open-minded. He was excellent at mathematics in primary school. A teacher encouraged him to apply for a scholarship to a military prep school called Lyceum Mânăstirea Dealu.

He won the scholarship in 1916, but World War I delayed his start. His mother moved the family to Bucharest, the capital, where they stayed with his grandmother. These were tough times, and Nicolae experienced the difficulties of war. He wanted to be a math teacher but struggled to keep up with schoolwork.

After the war, Nicolae returned to Constanța for the lyceum. The school had high standards and strict rules, including military exercises and uniforms. Students could only leave during holidays. Nicolae was an excellent student, especially in math. He later said that these five years gave him a great education. However, he also felt the strictness made him less social, which affected his relationships later in life.

At the lyceum, there was another student named Nicolae Georgescu. To avoid confusion, he added '-Roegen' to his last name. This came from the first and last letters of his first name, and the first four letters of his last name, spelled backward. He kept this name for the rest of his life and later changed his first name to 'Nicholas'.

Georgescu-Roegen finished the lyceum in 1923. He received a scholarship for poor families and was accepted at the University of Bucharest to study mathematics. The courses were traditional, like at the lyceum. He met Otilia Busuioc there, who later became his wife. To support himself, he gave private lessons and taught at a grammar school. After graduating with honors in 1926, he taught for another year at his old lyceum in Constanța.

At the university, he became close with Professor Traian Lalescu, a famous mathematician. Lalescu was interested in using math and statistics to study Romania's economy. He encouraged Georgescu-Roegen to study this abroad. In 1927, Georgescu-Roegen went to Paris to study at the Institute de Statistique, Sorbonne.

Studying in Paris and London

In Paris, Georgescu-Roegen studied more than just math. He attended lectures on statistics and economics and read about the philosophy of science. Life was hard for a poor foreign student, but his studies went very well. In 1930, he earned his doctorate with high honors. One of his professors, Émile Borel, was so impressed that he had Georgescu-Roegen's dissertation published.

While in Paris, Georgescu-Roegen learned about Karl Pearson at University College London. Pearson also studied mathematics, statistics, and philosophy of science. Georgescu-Roegen moved to London in 1931. His hosts taught him English, preparing him for his studies.

He was surprised by how open and informal the English university system was. He no longer felt like a 'stranger'. Studying with Pearson for two years and reading Pearson's book, The Grammar of Science, shaped Georgescu-Roegen's scientific thinking. They became friends and worked together on a difficult statistics problem, though they couldn't solve it.

While in London, the Rockefeller Foundation offered Georgescu-Roegen a research fellowship in the US because of his academic achievements. He accepted, planning to study time series analysis at Harvard University. However, he delayed his trip for a year to finish a manual in Romania and care for his sick mother.

Trip to the United States and Meeting Joseph Schumpeter

In autumn 1934, Georgescu-Roegen arrived at Harvard University. He found that the Economic Barometer project he wanted to join had been closed. After struggling to find research support, he met Joseph Schumpeter, a professor who taught about business cycles.

Meeting Schumpeter changed Georgescu-Roegen's life. Schumpeter welcomed him to Harvard and introduced him to a group of famous economists, including Wassily Leontief and Nicholas Kaldor. Georgescu-Roegen found a stimulating environment with weekly discussions. He later said, "Schumpeter turned me into an economist."

At Harvard, Georgescu-Roegen published four important papers that formed the basis of his later ideas on consumption and production. Schumpeter was impressed by their quality.

Georgescu-Roegen also traveled across the US with his wife, Otilia. He met other leading economists like Irving Fisher and Harold Hotelling, and even Albert Einstein at Princeton University.

Schumpeter wanted Georgescu-Roegen to stay at Harvard and offered him a position and a chance to write a book together. But Georgescu-Roegen declined. He felt he needed to return to Romania, which had supported his education. He later regretted this decision. In spring 1936, he left the US, stopping for a long visit with Friedrich Hayek and John Hicks in London before returning to Romania.

Life in Romania and Escape

From 1937 to 1948, Georgescu-Roegen lived in Romania. He experienced World War II and the rise of communism. During the war, he lost his only brother.

When he returned to Bucharest, Georgescu-Roegen was given several government jobs. His academic background and language skills were highly valued. He became vice-director of the Central Statistical Institute, dealing with foreign trade data. He also worked on trade agreements and even helped with talks about Romania's borders.

Georgescu-Roegen also joined the National Peasants' Party, which supported the monarchy. Romania's economy was mostly farming, and many peasants were poor. He worked hard for land reforms to reduce inequality. He rose to a high position in the party.

He did little academic work during this time, mostly co-editing a national encyclopedia and reporting on the economy. He later called this period his "Romanian 'exile'" because it was an intellectual exile for him.

After the war, the Soviet Union occupied Romania. As a trusted government official and party leader, Georgescu-Roegen was appointed general secretary of the Armistice Commission. He had to negotiate peace terms with the Soviets. These talks were long and stressful, as the Soviets demanded large war payments from Romania.

As communists gained power, Georgescu-Roegen faced increasing pressure. Romania had already gone through three dictatorships, and a fourth was coming. His high position in the Peasants' Party, his role in defending Romania against the Soviets, and his past connection to Harvard and the US made him a target. He realized he had to escape. He later said, "... I had to flee Romania before I was thrown into a jail from which no one has ever come out alive." With help from the Jewish community, whom he had helped during the war, he and his wife got fake ID cards. They escaped the country hidden on a freighter heading to Turkey.

In Turkey, Georgescu-Roegen used his contacts to tell Schumpeter and Leontief at Harvard about his escape. Leontief offered him a job at Harvard and made arrangements for him and his wife.

Settling in the United States and Vanderbilt University

After traveling through Europe from Turkey, Georgescu-Roegen and his wife sailed to the US. He arrived at Harvard in 1948, returning under very different circumstances. He was no longer a young scholar but a middle-aged political refugee. Still, he was welcomed and worked as a lecturer and research associate with Wassily Leontief. This job was not permanent.

Soon, Vanderbilt University offered him a permanent position as an economics professor. Georgescu-Roegen accepted and moved to Nashville, Tennessee, in 1949. Some believe he chose Vanderbilt for its stability after his difficult wartime experiences. He stayed at Vanderbilt until he retired in 1976 at age 70. He rarely left Nashville again.

At Vanderbilt, Georgescu-Roegen had an impressive academic career. He visited many universities, held research fellowships, and edited academic journals like Econometrica. He received several awards, including the Harvie Branscomb Award in 1967. In 1971, the same year his main book was published, he was honored as a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association.

In the early 1960s, Herman Daly was his student. Daly later became a leading ecological economist and a strong supporter of Georgescu-Roegen's ideas. However, Georgescu-Roegen later disagreed with some of Daly's work.

His big book, published in 1971, didn't immediately cause a stir among mainstream economists. One major journal even warned readers about its "incorrect statements." But other economists, who had different views, gave it good reviews.

In the 1970s, Georgescu-Roegen worked briefly with the Club of Rome. While his own book went largely unnoticed, the Club of Rome's 1972 report, The Limits to Growth, caused a big debate. Georgescu-Roegen agreed with the club and joined them. His ideas greatly influenced their work. He also wrote a popular article called Energy and Economic Myths, criticizing mainstream economists. Later, he disagreed with the club for not taking a stronger anti-growth stance and for relying too much on computer simulations. They eventually parted ways in the early 1980s.

Georgescu-Roegen's work became more influential in Europe from the 1970s. In 1974, he gave a lecture in Switzerland that impressed a young French historian, Jacques Grinevald. They became friends, and their cooperation led to a French translation of Georgescu-Roegen's articles in 1979, titled Demain la décroissance (Tomorrow, the Decline). This book helped spread his ideas among those who later started the degrowth movement. In the 1980s, he met and befriended Juan Martínez-Alier, who became a key figure in establishing the International Society for Ecological Economics and the degrowth movement. Leaders of the degrowth movement, like Serge Latouche and Mauro Bonaiuti, credit Georgescu-Roegen as a main source of their ideas.

Despite his influence, Georgescu-Roegen remained a solitary person at Vanderbilt. He rarely discussed his work with colleagues and had few collaborations. Many sources say he had a strong, uncompromising personality and a bad temper, which often offended people and limited his influence.

When he formally retired in 1976, a symposium was held in his honor. Four Nobel Prize winners were among the contributors, but none of his colleagues from his own department at Vanderbilt participated. This showed how isolated he was.

Retirement and Later Years

After retiring from Vanderbilt in 1976, Georgescu-Roegen continued to live and work in Nashville until his death in 1994. He wrote many articles, developing his ideas further, and corresponded with his few friends.

In 1988, he was asked to join the editorial board of the new journal Ecological Economics. However, he declined. He saw the journal and its society as promoting ideas like sustainable development and steady-state economics, which he disagreed with. He wanted to completely change the way economics was understood, not just be part of a small sub-field.

Georgescu-Roegen lived long enough to see the end of the communist dictatorship in Romania. He even received some recognition from his home country: after the Romanian Revolution in 1989, he was elected to the Romanian Academy in Bucharest, which pleased him.

His last years were marked by loneliness. Despite a successful career, he was disappointed that his work hadn't received the recognition he expected. He felt like a "heretic" who was running against the tide. He believed he had failed to warn the public about the coming mineral resource exhaustion. He realized that a pessimistic view, though true to him, is often avoided by society. Still, he kept writing and sharing his ideas as long as he could.

His health declined. He became deaf and had difficulty climbing stairs due to diabetes. In his final years, he completely isolated himself, even from those who admired his work. He died bitter and almost alone at 88. His wife, Otilia, died four years later. They had no children. As he wished, his ashes were returned to Romania and placed in Bellu Cemetery among other academics.

In his obituary, Herman Daly wrote that Georgescu-Roegen "demanded a lot, but he gave more." Another obituary praised him for the "novelty and importance of his contributions," saying he should have received the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen: His Ideas and Theories

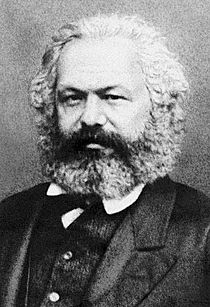

Georgescu-Roegen's economic ideas were shaped by the philosophy of Ernst Mach and logical positivism. He believed that economics should focus on real-world facts. He used this view to criticize both traditional economics (neoclassical economics) and Marxism.

When he came to the US after World War II, his background made him question the main economic ideas there. Having lived in underdeveloped Romania, he saw that traditional economics only explained rich countries, not others. He also disliked how economics was using more abstract math without connecting it to real life. This made him focus on social issues that mainstream economics often missed.

His work shows a clear path from his early theories to his writings on peasant economies, and finally to his focus on entropy and "bioeconomics" in his later years.

His Main Book: The Entropy Law and the Economic Process

Georgescu-Roegen said that the ideas in his most important book took about twenty years to develop. His main inspirations were:

- A book on thermodynamics by Émile Borel that he read in Paris.

- Joseph Schumpeter's idea that capitalism involves constant, irreversible change.

- The history of oil refineries in Ploiești, Romania, being attacked in both world wars, showing how important natural resources are in conflicts.

Why Traditional Economics and Marxism Missed Something

Georgescu-Roegen argued that both main economic ideas since the late 1800s – neoclassical economics and Marxism – failed to consider how important natural resources are to human economies. He felt he was fighting an intellectual battle on two fronts.

How Thermodynamics Connects to Economics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics with two main laws:

- The first law says that energy cannot be created or destroyed in a closed system; it only changes form.

- The second law, or entropy law, says that energy tends to degrade into less useful forms.

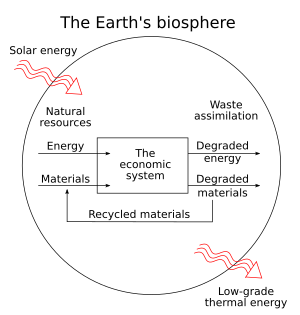

Georgescu-Roegen said that thermodynamics is important for economics because humans can only transform matter and energy, not create or destroy them. What we call 'production' and 'consumption' are just words that hide the fact that everything is simply being transformed.

Thermodynamics also predicts the heat death of the universe, where everything eventually reaches a state of uniform, unusable energy. Georgescu-Roegen believed that all human economic activities speed up this process locally on Earth. This idea led to the term 'entropy pessimism'.

Understanding Scarcity

Georgescu-Roegen used the term 'low entropy' for valuable natural resources and 'high entropy' for useless waste and pollution. He explained that the economic process turns low entropy into high entropy, providing resources for people. This process is irreversible, which is why natural resources are scarce. We can recycle materials, but it takes energy and other resources. Energy itself cannot be recycled; it becomes waste heat.

He pointed out that Earth is a closed system for matter: it exchanges energy (from the sun) but not much matter with the universe. So, humans have two main sources of low entropy:

- The limited stock of mineral resources in Earth's crust.

- The constant flow of radiation from the sun.

Since the sun will shine for billions of years, the mineral stock is much scarcer. We can choose how fast to extract minerals, but solar energy arrives at a fixed rate. This difference explains why busy city life (industry, quick mineral use) contrasts with calm rural life (agriculture, patient use of solar energy). Georgescu-Roegen argued this "asymmetry" helps explain why cities have historically dominated the countryside.

He explained that modern mechanised agriculture developed to feed more people. But this farming uses lots of mineral resources for machinery, fertilizers, and pesticides. This makes modern farming almost as dependent on Earth's minerals as industry. Georgescu-Roegen warned that this reduces Earth's carrying capacity. He believed that overpopulation is linked to growing mineral shortages.

The Production Process and the Flow-Fund Model

Georgescu-Roegen created his own model of the economy because he wasn't happy with existing theories. He realized that production involves not just equipment and materials, but also something new he called "funds."

In his flow-fund model, a "fund" is something that provides a useful service over time, like human labor, farmland, or machines. A "stock" is a material or energy input that can be used up. A "flow" is a stock used over a period. Funds are the "agents" that use the "flows." Unlike stocks, funds cannot be used up at will; their use depends on their physical limits (e.g., overusing farmland can exhaust it).

Georgescu-Roegen said that nature is the only original source of all production factors. According to the first law of thermodynamics, matter and energy are conserved in the economy. But the second law of thermodynamics (entropy law) means that all matter and energy are changed from useful states to unusable states. This is a one-way, irreversible process. So, valuable natural resources (low entropy) enter the economy, are transformed into goods, and eventually become useless waste and pollution (high entropy). Humans live from nature and return waste to nature, which increases the entropy of the combined nature-economy system.

Georgescu-Roegen's model, which includes natural resource flows, is different from traditional economic models. Only ecological economics fully recognizes these flows as a basis for economic analysis.

His production model later became the basis for his criticism of traditional economics. Since the 1980s, many economists have worked on his flow-fund model, applying it to various industries.

Human Economic Struggle and Social Evolution (Bioeconomics)

Georgescu-Roegen believed that human economic struggle is a continuation of our biological struggle to survive. This struggle has always existed. Unlike animals, humans use "exosomatic instruments" – tools and equipment not part of our bodies. Since production is a group effort, this struggle becomes a social conflict unique to humans.

He admitted that attempts to change how resources are shared can lead to wars or revolutions. But even after such changes, economic struggle and social conflict remain. There will always be rulers and ruled, and ruling is part of the biological struggle for survival. He claimed that ruling classes have always used force, ideas, and manipulation to keep their power. This doesn't end with communism; it continues. He believed it was against human biological nature to organize society differently.

Later, Georgescu-Roegen called his view "bioeconomics" (biological economics). He planned to write a book on it but couldn't finish it due to old age. He did write a short outline.

Population Pressure, Resource Depletion, and the End of Humanity

Georgescu-Roegen had a serious view of human nature and the future. He argued that Earth's carrying capacity is shrinking as we use up finite mineral resources. At the same time, he felt that humans cannot collectively limit themselves for future generations because it goes against our biological nature.

Therefore, he predicted that the world economy would keep growing until it collapses. After that, increasing shortages would cause widespread suffering, more social conflict, and intensify the struggle for survival. He believed this would lead to a long "biological spasm" for our species, eventually ending humanity. This is because humans have become completely dependent on the industrial economy for their existence. He concluded that we are doomed to decline and destruction.

His very serious view on global mineral resource depletion was later challenged by other scientists.

Later Work After His Main Book

After his main book in 1971, Georgescu-Roegen wrote more articles and essays until his death in 1994, expanding on his ideas.

Criticizing Neoclassical Economics (Weak vs. Strong Sustainability)

Georgescu-Roegen criticized neoclassical production theory for showing the economy as a simple, circular system with no inputs or outputs. He said this view ignores the depletion of mineral resources and the buildup of waste and pollution. His flow-fund model, he argued, was a more accurate way to show the economy.

He also believed that traditional economics often missed or misunderstood the problem of how to share exhaustible mineral resources between current and future generations. He pointed out that market mechanisms (supply and demand) cannot solve this problem fairly because future generations are not part of today's market. He called this market failure "a dictatorship of the present over the future."

Economists like Robert Solow and Joseph Stiglitz, who were his main academic opponents in the 1970s, argued that human-made capital can largely replace natural capital. So, they believed concerns about sharing minerals across generations should be less important or even ignored. This view was later called 'weak sustainability'.

Georgescu-Roegen argued against Solow and Stiglitz. He said that neoclassical economists don't understand the key difference between material resources and energy resources. His flow-fund model showed that only material resources can be turned into human-made capital. Energy, however, cannot be turned into matter; it can only help transform materials. So, you cannot replace energy resources with human-made capital.

He also noted that not all materials become capital; some become consumer goods that don't last. All human-made capital eventually wears out and needs to be replaced with new material resources. Overall, he argued that the economic process always increases entropy, and the idea that everything can be easily replaced is wrong.

Georgescu-Roegen concluded that natural resources and human-made capital are essential and work together. Therefore, the problem of sharing exhaustible mineral resources between generations is a huge issue that cannot be ignored. He said, "There seems to be no way to do away with the dictatorship of the present over the future, although we may aim at making it as bearable as possible." His followers have discussed how it's impossible to share Earth's finite minerals evenly among an unknown number of future generations. This means any sharing plan will eventually lead to economic decline. This idea is missing from traditional economics.

He strongly rejected the idea of sustainable development, calling it "snake oil" meant to trick people. He believed there could be no such thing as a 'sustainable' rate of using non-renewable mineral resources because any use reduces the remaining stock. He concluded that the Industrial Revolution started an unsustainable economic path.

Criticizing Herman Daly's Steady-State Economics

Herman Daly, a leading ecological economist and former student of Georgescu-Roegen, developed the idea of a steady-state economy. This is an economy with a constant amount of physical wealth (machines, buildings) and a constant population, both maintained by a minimal flow of natural resources. Daly argued this was necessary to stay within Earth's limits and share resources fairly. Georgescu-Roegen criticized this idea in several articles.

Georgescu-Roegen argued that Daly's steady-state economy would not save humanity, especially in the long run. Because mineral ores are not evenly spread in Earth's crust, finding and extracting them eventually faces diminishing returns. This means it takes more effort and cost to get less accessible or lower-grade ores. Eventually, all minerals will be used up, but the economic exhaustion will happen long before the physical exhaustion. There will still be minerals left, but they will be too hard or expensive to extract. This long-term trend will affect any economic system.

He argued that if the goal is to make mineral resources last as long as possible, then negative economic growth (shrinking the economy) is even better than zero growth (a steady state). He also criticized Daly for not saying at what levels the human-made capital and population should be kept constant in the steady state.

Instead of Daly's steady-state economics, Georgescu-Roegen proposed his own "minimal bioeconomic program", which suggested even stricter limits than Daly's.

Herman Daly later agreed with his teacher's points. He admitted that to deal with diminishing returns in mining, more capital and labor would have to go into mining, changing the steady-state economy. More importantly, he conceded that a steady-state economy would only postpone, not prevent, the inevitable mineral exhaustion. Daly confirmed Georgescu-Roegen's main argument that Earth's carrying capacity is decreasing as humanity uses up finite minerals. Other economists also agree that a steady-state economy alone isn't a long-term solution to the "entropy problem."

Looking at Technology Through History

Georgescu-Roegen used thermodynamic principles to assess technology in a historical context, including the future of humanity.

He defined a technology as 'viable' only if it produces enough energy to run itself and have extra energy for other uses. If it doesn't, it's only 'feasible' (it works) but not 'viable'. Both viable and feasible technologies need a constant flow of natural resources.

He believed the first viable technology in human history was fire. By controlling fire, humans could burn forests, cook food, and get warmth and protection. He called fire 'the first Promethean recipe', inspired by the Greek myth of Prometheus who stole fire for humans. He also saw animal husbandry (raising animals) as another important "Promethean recipe" of the first kind, as it also used biomass like fire.

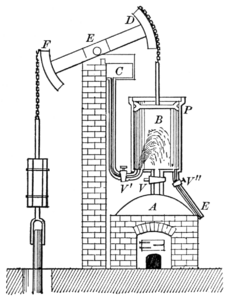

Much later, the steam engine became the crucial "Promethean recipe of the second kind," powered by coal. This invention allowed mines to be drained and coal to fuel other steam engines. This started the Industrial Revolution in Britain, pushing the global economy onto a path of using up Earth's minerals too quickly. Georgescu-Roegen also listed the internal combustion engine (using oil) and the nuclear fission reactor (using uranium) as other examples of this second kind of "heat engine" technology.

A "Promethean recipe of the third kind" for Georgescu-Roegen would be a solar collector that produces enough energy to make another solar collector of the same type, using only solar energy. He believed that no such truly self-sufficient solar technology existed in his day. He saw existing solar collectors as "parasites" because they relied on Earth's energy inputs for their manufacture and operation. He thought a new kind of solar collector was needed for a truly solar-powered economy. Some scholars today argue that solar collector efficiency has greatly improved since his time.

He also noted that solar power's main drawback compared to fossil fuels and uranium is that solar radiation is spread out and not very intense. This means a lot of material equipment is needed to collect, concentrate, and store solar energy for industrial use. This equipment adds to the "parasitical" nature of solar power, he argued.

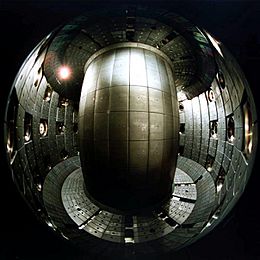

When looking at fusion power as a future energy source, Georgescu-Roegen doubted that a magnetic confinement fusion reactor could ever be built large enough to contain the extreme heat and pressure needed for a long time (which is required for the technology to be 'viable'). He didn't assess inertial confinement fusion, another type of fusion technology.

All these technology assessments focused on energy resources, not material resources. Georgescu-Roegen stressed that even with widespread solar power or fusion power, any industrial economy would still need a steady flow of metals and other materials from Earth's crust. He repeatedly argued that in the future, the scarcity of Earth's material resources, not energy, would be the biggest limit on human economy. He didn't believe in space advocacy or asteroid mining as solutions. He was convinced that humanity would remain confined to Earth for all practical purposes throughout its existence. This was his final, serious vision.

Awards and Prizes

The Georgescu-Roegen Prize

Since 1987, the Southern Economic Association has given out the Georgescu-Roegen Prize each year. It is awarded for the best academic article published in the Southern Economic Journal.

The Georgescu-Roegen Annual Awards

In 2012, The Energy and Resources Institute in New Delhi, India, created two awards to honor Georgescu-Roegen's life and work. They were announced on his 106th birthday. The awards have two categories:

- The 'unconventional thinking' award is for scholarly work.

- The 'bioeconomic practice' award is for efforts in politics, business, and community groups.

Japanese ecological economist Kozo Mayumi, who studied with Georgescu-Roegen, was the first to receive the 'unconventional thinking' award for his work on energy analysis.

Famous Quotes

- "'Bigger and better' motorcycles, cars, jet planes, refrigerators, etc., not only use up more natural resources but also cause more pollution."

- "William Petty was right when he said 'Nature is the mother and labor is the father of all wealth' — but he should have said '... of our existence'."

- "Will people listen to a plan that means giving up some of their modern comforts? Maybe humans are meant to have a short, exciting, and extravagant life instead of a long, boring, and simple one. Let other species, like amoebas, who have no social ambitions, inherit an Earth still full of sunshine."

Images for kids

-

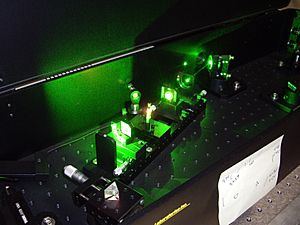

The Breit–Wheeler process represents the only known example of a process where energy (photons) is transformed into mass (positron-electron pairs); but even in this special experimental case, the resulting elementary particles cannot combine to form atomic structures having economic value. A process where pure energy is transformed into useful materials remains to be discovered.

-

Prometheus I: The mastering of fire in the Palaeolithic Era.

See also

In Spanish: Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen para niños

In Spanish: Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen para niños

- Ecological economics

- Degrowth movement: Lasting influence on

- Steady-state economy: Herman Daly's concept of it

- The Limits to Growth

- Sustainability: Carrying capacity

- Human overpopulation

- Peak minerals

- Market failure: Ecological market failure

- Sustainable development: Insubstantial stretching of the term

- The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI)

- Entropy

- Heat death of the universe

- Pessimism: Philosophical pessimism

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |