Seahorse facts for kids

Quick facts for kids HippocampusTemporal range: Lower Miocene to Present

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Hippocampus sp. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: |

Syngnathidae

|

| Genus: |

Hippocampus

Cuvier, 1816

|

Seahorses are a special type of fish. They belong to the group called Hippocampus. People call them 'seahorses' because their heads look a lot like a horse's head. There are about 32 to 48 different kinds, or species, of seahorses. You can find seahorses living in warm, tropical parts of the ocean.

Seahorses are very good at using camouflage to hide from other animals.

Contents

About Seahorses

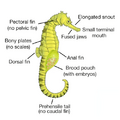

Seahorses come in many sizes. They can be as small as 1.5 cm (0.6 in) or as big as 35 cm (13.8 in). They have bent necks and long snouts. Their bodies are covered in thin skin over bony plates, not scales. These bony plates act like armor, protecting them from animals that might want to eat them. Each type of seahorse has a different number of these bony rings.

Seahorses swim in a unique way. They swim upright, using a fin on their back called the dorsal fin to push themselves through the water. This is different from most other fish, which swim flat. They use small fins near their eyes, called pectoral fins, to steer. Seahorses do not have a tail fin like most fish. Instead, they have a special tail that can grab onto things, like a monkey's tail. This is called a prehensile tail.

Seahorses are masters of disguise. They can change their appearance to blend in with their surroundings. They can even grow or shrink spiky parts on their bodies to match their habitat.

How Seahorses Move and See

Seahorses are not very fast swimmers. They flutter their dorsal fin quickly and use their pectoral fins to steer. The slowest fish in the world is the dwarf seahorse, which moves at only about 1.5 m (5 ft) per hour!

Because they are slow, seahorses often rest by wrapping their tails around plants or corals. Their long snouts help them suck up tiny food. Also, their eyes can move separately, just like a chameleon's eyes. This means one eye can look forward while the other looks backward!

Seahorse Communication

Seahorses make clicking sounds to talk to each other, especially when they are looking for a mate. They can also make a growling sound if they are stressed, but humans usually can't hear it. Besides sounds, seahorses use their body movements and special chemicals called pheromones to communicate.

What Seahorses Eat

Seahorses use their long snouts to easily eat their food. They eat very slowly and have a simple digestive system without a stomach. This means they need to eat almost all the time to stay alive.

Since seahorses are not strong swimmers, they need to hold onto things like seaweed or coral. They use their prehensile tails to grasp onto these objects. Seahorses mostly eat small crustaceans that float in the water or crawl on the bottom. They are very good at hiding, so they wait quietly until a small animal swims close enough. Then, they quickly suck it up!

Their special head shape helps them sneak up on their prey without being noticed. When they are close, they quickly snap their head up and suck in the food. This quick movement is called "pivot-feeding."

Seahorses have three main steps when they eat:

- Getting Ready: The seahorse slowly moves closer to its prey while staying upright.

- Eating: It quickly lifts its head, opens its mouth, and sucks in the food.

- Recovering: The seahorse's mouth and head go back to their normal position.

The amount of plants or hiding spots in their home can change how seahorses eat. In places with few plants, they might wait for food to come to them. But in places with lots of plants, they might swim around more to find food.

Seahorse Reproduction

Seahorses are very special because the male seahorse carries and hatches the eggs in a pouch on his belly. This is called male pregnancy.

Here's how it works:

- The female uses a special tube called an ovipositor to put her eggs into the male's pouch.

- She can lay dozens to thousands of eggs. As she lays the eggs, her body gets thinner, and his pouch swells up.

- The male then releases his sperm into the water. The sperm fertilizes the eggs inside his pouch.

- The fertilized eggs stick to the inside of the pouch. They get nutrition and oxygen from the fluid in the pouch.

- The pouch also controls the saltiness of the water. This helps the baby seahorses get ready for life in the ocean.

After the eggs are in the pouch, the female swims away. She visits the male every morning for a "morning greeting" during the two to four weeks he carries the eggs. They spend about 6 minutes together before she swims off again.

Birth of Baby Seahorses

The number of baby seahorses born can vary a lot. Smaller seahorse species might have only 5 babies, while larger ones can have up to 1,500! On average, most species release about 100 to 200 young.

When the babies are ready, the male pushes them out of his pouch using strong muscle movements. He usually gives birth at night. By morning, he is ready to carry the next batch of eggs from his mate.

Unlike many animals, seahorses do not take care of their young after they are born. The tiny baby seahorses, called fry, are on their own. They can be easily eaten by other animals or swept away by ocean currents. Because of this, very few baby seahorses (less than 0.5%) survive to become adults. This is why seahorses have so many babies at once. Even with this low survival rate, it's actually quite good compared to other fish, because the eggs are protected inside the father's pouch. Most other fish eggs are left alone after they are fertilized.

Threats to Seahorses

Scientists don't have enough information about seahorse populations to know exactly how many are left. It's hard to tell how many are born, how many die, or how many are caught each year. Because of this, there's a concern that some seahorse species might be in danger of disappearing forever. Some, like the paradoxical seahorse, might even be gone already.

The places where seahorses live, like coral reefs and seagrass beds, are being damaged. This means seahorses have fewer safe homes. Also, many seahorses are accidentally caught in fishing nets, which is called bycatch. It's estimated that about 37 million seahorses are caught this way each year in many countries.

Seahorses in Aquariums

Many people like to keep seahorses as pets in aquariums. However, seahorses caught from the wild often don't do well in home tanks. They might only eat live food and can get stressed easily, which makes them sick.

Luckily, more and more seahorses are now being raised in captivity. These captive-bred seahorses are healthier and easier to care for. They eat frozen foods that you can buy at pet stores. They also don't get stressed from being taken out of the wild. Even though they cost more, buying captive-bred seahorses helps protect wild populations.

If you keep seahorses, their tank needs to be calm with slow water flow. Seahorses are slow eaters, so they need tank mates that are also slow and peaceful. Good tank mates include many types of shrimp and other animals that live on the bottom. Gobies can also be good friends for seahorses. It's best to avoid eels, tangs, triggerfish, squid, octopus, and sea anemones.

Keeping the water clean and healthy is very important for seahorses. They are delicate fish. The tank should be deep, ideally twice as deep as the adult seahorse is long, because they like to swim up and down.

Sometimes, people sell fish called "freshwater seahorses," but these are usually pipefish, which are related to seahorses. True seahorses do not live in freshwater.

Images for kids

-

Diagram of a pregnant male seahorse (Hippocampus comes)

-

Pregnant male seahorse at the New York Aquarium

-

H. kuda, known as the "common seahorse"

See also

In Spanish: Caballito de mar para niños

In Spanish: Caballito de mar para niños