Semyon Budyonny facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

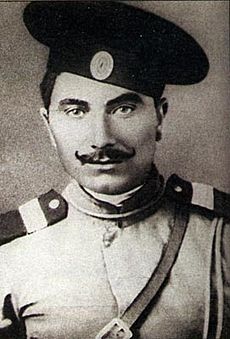

Semyon Budyonny

|

|

|---|---|

Budyonnyy in 1943

|

|

| Birth name | Semyon Mikhailovich Budyonnyy |

| Born | 25 April 1883 Platovskaya, Don Host Oblast, Russian Empire |

| Died | 26 October 1973 (aged 90) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Buried |

Kremlin Wall Necropolis, Moscow

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

Imperial Russian Army |

| Years of service | 1903–1954 |

| Rank | Marshal of the Soviet Union (1935–1954) |

| Commands held | 1st Cavalry Army Moscow Military District Southwestern Direction

North Caucasus Front |

| Battles/wars | Russo-Japanese War World War I Russian Civil War Polish-Soviet War World War II

|

| Awards | Hero of the Soviet Union (thrice) Cross of St. George, 1st–4th Classes |

| Other work | Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1919–1973) |

Semyon Mikhailovich Budyonny (Russian: Семён Миха́йлович Будённый, tr. Semyon Mikháylovich Budyonnyy, IPA: [sʲɪˈmʲɵn mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ bʊˈdʲɵnːɨj]; 25 April [O.S. 13 April] 1883 – 26 October 1973) was a famous Russian cavalryman and military leader. He played a big role in the Russian Civil War, the Polish-Soviet War, and World War II. He was also a close friend and political supporter of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.

Born into a poor farming family in southern Russia, Budyonny joined the army in 1903. He fought bravely in World War I and earned many awards. During the Russian Civil War, he created the Red Cavalry. This group was very important in helping the Bolsheviks win. Budyonny became known for his courage and was even featured in popular patriotic songs. He became one of the first five Marshals of the Soviet Union. He was one of only two top army commanders who survived the Great Purge. In 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union, his forces faced huge challenges. After major defeats, he was removed from frontline command but remained a part of the Soviet leadership.

Budyonny strongly believed in using horse cavalry in war. He thought tanks were not as good as horses. He once said, "You won't convince me. As soon as war is declared, everyone will shout, 'Send for the Cavalry!'"

Contents

Early Life and Military Start

Budyonny was born on April 25, 1883, into a poor farming family. This was in the Don Cossack region of the southern Russian Empire. Even though he grew up in a Cossack area, his family was Russian.

Before joining the army, he worked many jobs. He was a farm worker, a shop helper, and a blacksmith's apprentice. In 1903, he was drafted into the Imperial Russian Army. He became a cavalry soldier and fought in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905).

After that war, he joined the Primorsk Dragoon Regiment. In 1907, he went to a special school for cavalry officers in Saint Petersburg. He did very well, finishing first in his class. He then became a riding instructor. When World War I began, he joined a cavalry battalion.

Fighting in World War I

During World War I, Budyonny was a non-commissioned officer in a cavalry division on the Eastern Front. He became famous for a brave attack on a German supply convoy. For this, he received the Cross of St. George, 4th Class.

Later, his division moved to fight the Ottoman Turks. He had a conflict with a senior officer about how soldiers were treated and a lack of food. Budyonny punched the officer. Other soldiers supported him, saying the officer was kicked by a horse. Budyonny lost his St. George Cross, but he avoided a serious military trial.

He later earned the St. George Cross, 4th class, a second time during the Battle of Van. He then received the 3rd class and 2nd class crosses for fighting the Turks. Finally, he earned the 1st class cross for capturing an enemy officer and six soldiers.

Leading the Red Cavalry

After the February Revolution in 1917, which ended the rule of the Tsar, Budyonny became involved in soldier committees. He returned to his hometown and helped organize a group of 24 men to fight against the White Guards. This group quickly grew to 520 men. On February 27, 1918, he formed what became the first 120-strong squadron of Red Cavalry.

In July 1918, Budyonny met Joseph Stalin and Kliment Voroshilov. They supported his idea of creating a large cavalry force for the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. However, Leon Trotsky, the War Commissar, did not like the idea of cavalry.

Despite Trotsky's doubts, the 1st Socialist Cavalry Regiment was formed in October 1918. Budyonny joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1919. In October 1919, Budyonny led his cavalry to a great victory against the White army. Trotsky then praised Budyonny as "a true warrior of the workers and peasants."

During the Polish–Soviet War

In April 1920, Budyonny's cavalry was sent to push the Polish army out of Ukraine. They recaptured Kiev and drove the Poles westward. Budyonny was assigned to the southern front, which Stalin commanded. He tried to capture Lviv but was unsuccessful. He then moved north to help other Soviet forces, but it was too late. His army was defeated in the Battle of Komarow, one of the biggest cavalry battles in history. He had to retreat.

After this, Budyonny took part in the final battles of the Russian Civil War in Crimea.

His Reputation and Later Career

Even with the defeat in Poland, Budyonny was seen as a hero after the Civil War. He was a strong supporter of Joseph Stalin. In 1920, a popular song called "Budyonny's March" was written about him.

The writer Isaac Babel rode with Budyonny's cavalry and wrote short stories about his experiences. These stories became famous but made Budyonny angry. He felt they made the Red Cavalry look bad.

From 1921 to 1923, Budyonny was a deputy commander in the North Caucasian Military District. He also became assistant commander of the Red Army's cavalry. He spent a lot of time working on horse breeding and improving equestrian facilities.

Budyonny was known as a brave cavalry officer. However, he did not believe in modern warfare tools like tanks. He thought tanks could never replace cavalry. This led to disagreements with other military leaders who saw the future of mechanized warfare. Even so, Budyonny remained a loyal ally of Stalin and was never criticized for his views on tanks.

He graduated from the M. V. Frunze Military Academy in 1932. In 1935, Budyonny became one of the first five Marshals of the Soviet Union. Three of these five were later executed during the Great Purge, leaving only Budyonny and Voroshilov.

Role During the Great Purge

During the Great Purge, a time when many people were arrested and executed in the Soviet Union, Budyonny was appointed commander of the Moscow Military District. He was a judge in the trial of other Red Army commanders. He survived this dangerous period.

Second World War Service

In 1941, Budyonny was Commander-in-Chief of Soviet forces in Ukraine, facing the German invasion known as Operation Barbarossa. Stalin gave strict orders not to retreat. As a result, Budyonny's forces were surrounded in the Battle of Uman and the Battle of Kiev. These battles led to huge losses for the Soviet Union.

On September 13, 1941, Stalin removed Budyonny from his command. He was replaced by Semyon Timoshenko. Budyonny was never again allowed to command troops in combat. He was given other roles, like Cavalry Inspector of the Red Army.

Some of his fellow officers believed Budyonny was not good at commanding an army in a modern, mechanized war. However, because of his heroic past in the Civil War and his popularity, he remained in Stalin's favor and did not face severe punishment for the defeats.

Life After the Wars

After World War II, Budyonny was put in charge of agriculture in the USSR, with a special focus on horse breeding. He retired but remained a member of the Supreme Soviet, a high-level government body.

Semyon Budyonny died on October 26, 1973, at the age of 90. He was buried with full military honors in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow. Important leaders attended his funeral.

His Legacy

Budyonny wrote a five-volume memoir about his experiences in the Civil War. He was often celebrated in Soviet military songs, like The Red Cavalry song. The Budenovka, a type of Soviet military hat, is named after him.

Budyonny was also a famous horse breeder. He created a new horse breed called the Budyonny horse. These horses are known for being good at sports and having great endurance.

He was also an amateur bayan player (a type of accordion). He even released some music records with a friend. The Military Academy of the Signal Corps in St. Petersburg is named in his honor.

Personal Life

Budyonny was married three times and had children. His last marriage to Maria Vasilevna lasted until his death. They had two sons, Sergei and Mikhail, and a daughter, Nina.

Honours and Awards

- Russian Empire

| Cross of St. George, all four-classes (Full Cavalier). | |

| St. George Medal, all four-classes (Full Cavalier) |

- Soviet Union

| Hero of the Soviet Union, three times (1958, 1963, 1968) | |

| Order of Lenin, eight times (1935, 1939, 1943, 1945, 1953, 1963, 1968, 1973) | |

| Order of the Red Banner, six times (1919, 1923, 1930, 1941, 1944, 1968) | |

| Order of Suvorov, 1st class (1944) | |

|

|

Order of the Red Banner of Azerbaijan SSR (1923) |

|

|

Order of the Red Banner of Labour of Uzbek SSR (1930) |

| Medal "For the Defence of Moscow" (1944) | |

| Medal "For the Defence of Sevastopol" (1942) | |

| Medal "For the Defence of Odessa" (1942) | |

| Medal "For the Defence of the Caucasus" (1944) | |

| Medal "For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1945) | |

| Medal "For the Victory over Japan" (1945) | |

| Jubilee Medal "Twenty Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945" (1965) | |

| Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (1969) | |

| Jubilee Medal "XX Years of the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army" (1938) | |

| Jubilee Medal "30 Years of the Soviet Army and Navy" (1948) | |

| Jubilee Medal "40 Years of the Armed Forces of the USSR" (1958) | |

| Jubilee Medal "50 Years of the Armed Forces of the USSR" (1968) | |

| Medal "In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow" (1947) | |

| Medal "In Commemoration of the 250th Anniversary of Leningrad" (1957) |

Honorary weapon – sword with golden national emblem (1968)

Honorary weapon – sword with golden national emblem (1968)- Honorary weapon – sword with Order of the Red Banner

- Honorary weapon – Mauser C96 pistol with Order of the Red Banner

- Foreign awards

| Medal of Sino-Soviet Friendship (China) | |

| Order of Sukhbaatar, twice (Mongolia) | |

| Order of the Red Banner, (Mongolia, 1936) | |

| Order of Friendship (Mongolia, 1967) | |

| Medal "50 years of the Mongolian People's Revolution" (Mongolia, 1970) | |

| Medal "50 years of the Mongolian People's Army" (Mongolia, 1970) | |

| Order of Polonia Restituta, 3rd class (Poland, 1973) |

See also

In Spanish: Semión Budionni para niños

In Spanish: Semión Budionni para niños