Siege of Silves (1189) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Silves |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Crusade and Reconquista | |||||||||

A tower of Silves today |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Kingdom of Portugal Crusaders from northern Europe |

Almohad Caliphate | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Sancho I of Portugal | ʿĪsā ibn Abī Ḥafṣ ibn ʿĀlī | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 75 ships 3,500 crusaders + Portuguese army |

15,800 inhabitants 400 prisoners |

||||||||

The siege of Silves was a big battle that happened in 1189. It was part of the Third Crusade, which was a series of religious wars, and the Portuguese Reconquista, which was a long effort by Christian kingdoms to take back land from Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal).

The city of Silves was a strong city controlled by the Almohad Caliphate, a Muslim empire. It was attacked from July 21 to September 3 by forces from Portugal and a group of crusaders from northern Europe. These crusaders were on their way to the siege of Acre in the Middle East.

The defenders of Silves eventually gave up. The city was then given to Portugal, and the crusaders took some of the valuable items found there.

A call for a new crusade went out in 1187 after the city of Jerusalem was captured. The first fleets of crusaders from northern Europe arrived in Portugal in the spring of 1189. One of these groups attacked a town called Alvor and killed many people.

A few weeks later, the fleet that would attack Silves gathered in Lisbon in early July. This combined fleet of Portuguese and crusader ships had 75 vessels. It included 37 large northern European ships called cogs and 38 galleys. About 3,500 crusaders were on board. King Sancho I of Portugal marched his own army overland to join them.

The crusaders set up camp outside Silves on July 20. The next day, they launched an attack using scaling ladders. They managed to capture the lower part of the city, which had walls. Then, they started preparing large siege engines to attack the main city.

King Sancho arrived on July 29, and his army joined him a day later. At this point, Silves was completely surrounded. The attack with siege engines began on August 6. On August 9, they started trying to dig tunnels under the city walls and towers. This continued with different levels of success until the end of the siege. The defenders also dug tunnels to fight back underground. They might have even used something like Greek fire, a burning liquid, against the attackers.

On August 10, a part of the city's defenses called the breastwork was captured. By mid-August, the people inside Silves were running out of water. On September 1, the Portuguese offered terms for surrender, and the defenders agreed to talk. The crusaders wanted to take all the valuable items, but the defenders were allowed to leave peacefully.

On September 3, the city was given to King Sancho. He let the crusaders enter to divide the valuable items. After a while, the crusaders left the city. King Sancho set up a military group to protect Silves and left on September 12.

When Silves fell, nine other smaller castles nearby also came under Portuguese control. The town of Albufeira also surrendered. However, the crusaders refused to help attack Faro and sailed away on September 20 to continue their crusade.

The Portuguese victory at Silves did not last long. In April 1190, the Caliph Yaʿqūb al-Manṣūr launched an attack to take Silves back. His first attempt failed, but he tried again in April 1191. Silves was recaptured by the Almohads in July of that year.

Contents

About Silves and Its Defenses

Silves: A Key City

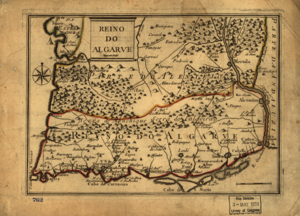

Silves, also known as Shilb or Xelb in Arabic, is located about 8 miles (13 km) up the Arade River from the coast. It sits on a hill about 200 feet (60 meters) high. A bridge crossed the river at this point. In 1189, about 15,800 people lived in Silves.

The city came under the rule of the Almohad Caliphate in 1146. It became directly controlled by them in 1157. Silves was the capital of the region called al-Gharb. The governor of Silves in 1189 was ʿĪsā ibn Abī Ḥafṣ ibn ʿĀlī. He was known for being very good at defending borders.

Strong Fortifications

Because Silves was so important, its fortifications (defensive walls and towers) were very strong. The Almohads had repaired them after taking control in 1157. The hilltop was surrounded by a wall made of packed earth and stone. It had at least seventeen special towers called albarrana towers. These towers were built outside the main wall but connected to it by raised walkways. The tower near the main gate was especially large. These towers were solid and as tall as the walls, acting as elevated fighting platforms.

Two parallel walls went down from the hilltop to the river. These walls protected the city's water supply and had four towers. This walled section leading to the river was called a couraça, meaning "breastwork". The part of the city at the base of the hill had weaker walls and only one tower.

Challenges for the Defenders

Even though the governor was experienced, he had not prepared enough supplies for a long siege. There had been a drought, which meant the water in Silves's harbor was very low. Five galleys (ships) were stuck there. Besides a lack of food and water, there was also a shortage of armor and soldiers. Four hundred Christian prisoners had to be forced to fight.

Planning the Attack

Portugal's Strategy

In October 1187, Jerusalem was captured by the Ayyubids, a Muslim dynasty. Pope Gregory VIII then called for a new crusade to take it back. King Sancho of Portugal saw this as a chance to get help from crusaders on their way to the Middle East. Crusader fleets had helped Portugal before, like during the conquest of Lisbon in 1147.

The first crusader fleet to arrive had fifty to sixty ships from Denmark and Frisia. They came in June 1189. King Sancho invited them to help capture Alvor. However, they killed many of its people, which was against the usual rules of war. After taking their share of the valuable items, they sailed on. Sancho and his forces returned to Lisbon to wait for the next group of crusaders.

Crusaders' Journey to Portugal

In April 1189, a fleet of eleven crusader ships left Bremen in Germany. The person who wrote the Narratio (a historical account) was on one of these ships. He wrote that the group of crusaders changed as some joined later and others left. Most of them seemed to be from northern Germany.

The fleet sailed from the mouth of the Weser River on April 22. They arrived in England on April 24. Three ships got stuck in a storm while trying to enter the port of Sandwich. Only one ship could be saved. Repairs took 23 days.

After buying a new ship in London, the fleet left Sandwich on May 19. They sailed along the coast of England, stopping at various ports. Some men from London might have joined them here. The fleet then sailed to Brittany in France and then across the Bay of Biscay to Spain. They arrived in the kingdom of León on June 18.

Some crusaders went on a short pilgrimage to Oviedo Cathedral. Others went on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. A ship from Tui in Galicia joined the fleet, bringing its size back to eleven ships. The fleet then sailed on July 1 and arrived in Lisbon on July 3 or 4.

The Campaign: July to September

Getting Ready for Battle

In Lisbon, the crusaders heard about the attack on Alvor. They were invited to join an attack on Silves. King Sancho agreed that the crusaders could keep any valuable items they took if they recognized his right to the city.

There were many other ships in Lisbon's harbor at that time. The crusader fleet now had 36 large ships and one Galician ship. They stayed in Lisbon for eleven days.

On the evening of July 14, the fleet sailed from Lisbon towards Silves. King Sancho also sent a fleet of 37 galleys and many smaller boats. The crusader army had about 3,500 men, which is believed to be accurate. Most of the crusaders were common people, not noblemen.

The fleets entered the Arade River on July 17. The land was empty because people had fled to the city. Raiding parties were sent out to take valuable items and burn nearby villages. On July 18, the Portuguese commander met with the crusaders to plan the attack. He suggested attacking a different place, but the crusaders refused.

On July 19, the crusaders sailed up the Arade River as far as they could, while the Portuguese army marched ahead of them. On July 20, they approached Silves in small boats and set up camp close to the city walls. Some crusaders charged at enemy cavalry and suffered losses. The camp was moved closer to the walls of the lower town, and the crusaders spent the day preparing ladders for an attack the next morning.

The Siege Begins

Attacks and the Fall of the Lower Town

The siege began with an attack on the walls of the lower town on July 21. The Portuguese and crusaders attacked from different directions. The defenders put up weak resistance and then retreated to the main city. The lower town was left in the hands of the attackers.

On July 22, the army launched an attack with ladders against the main city, but they were pushed back. Both sides fired many arrows and other projectiles. That evening, the crusaders' camp was moved right up to the walls of the captured lower town. They started building siege engines.

King Sancho arrived on July 29 with more soldiers and supplies. His army arrived on July 30, and the city was completely surrounded. The crusader army of 3,500 was not enough to surround the entire city by themselves.

While building the siege engines, the crusaders were also fighting with arrows and machines. The main attack with engines began on August 6. The Germans pushed a battering ram up to the wall, but the defenders set it on fire and destroyed it. On August 7, a German siege engine started firing at two towers, while Sancho's two engines bombarded the people inside the city.

Taking the Breastwork

On August 8, a Muslim defector came to Sancho's camp. This person might have promised to help hand over the city once the breastwork was captured. After this, the attackers focused on the breastwork, which was a weaker part of the defenses.

On August 9, the crusaders began digging tunnels under the walls of the breastwork. The next morning, they lit the wooden supports in the tunnel, and part of the tower collapsed. More digging brought down more of the wall. The attackers managed to enter using ladders, while the defenders retreated to the upper fortress. The wall was then destroyed in two places, and the well the city used for water was filled in.

Attacking the Upper City

On August 11, the crusaders started digging tunnels under the main city walls. But the next day, the defenders rushed out and burned the tunneling works. The Flemish crusaders tried to dig through a wall to reach a tower of the upper city. However, the defenders destroyed that section of the wall on August 13.

The people inside the city were suffering from thirst, and more of them started leaving. Many people fled to the attackers to save their lives. One person who fled said that many enemies were dying of thirst because they had very little water left.

A large attack was launched on August 18 using scaling ladders, but it was pushed back. An attempt to fill in the ditch around the city was also stopped. The Portuguese army wanted to leave after these failures, but the crusaders refused, and King Sancho agreed with them.

The attackers then focused on the north wall with their siege engines. The crusaders had four, and the Portuguese had three. The defenders inside the city had four engines to fight back. A new tunnel was started far from the wall to avoid being noticed early. However, the defenders saw it and rushed out twice, being pushed back on August 22.

On August 23, there was a disagreement between the crusaders and the Portuguese. The king again suggested leaving. He finally agreed to stay for another four days. During this time, a new tunnel was started. The defenders dug tunnels to meet them, and a battle was fought underground. The attackers were pushed back by a "fiery flood," possibly Greek fire. The defenders also dug a trench inside the wall to be ready if the attackers tunneled under it. Work on the tunnel and underground fighting continued until the city surrendered. At least one of the towers was completely ruined.

Talking and Giving Up

On September 1, the Portuguese offered the defenders a chance to surrender, and talks began. Many people left the city at this stage. The defenders agreed to surrender if they could keep their movable property and leave peacefully. King Sancho offered the crusaders 10,000 gold coins to give up their right to take valuable items, but they refused. They then accepted 20,000 gold coins, but when it seemed it would take time for the king to get the money, they changed their minds. They only agreed that the defenders could leave unharmed with the clothes they were wearing. The governor accepted these terms on September 2.

On September 3, the city was handed over. The surrender was made to King Sancho, not the crusaders. The governor rode out, and the rest followed on foot. Some crusaders did not follow the agreement and robbed the departing Muslims. They even tortured some people in the city to find hidden valuable items. The defenders were weak and thin from lack of water. Of the 450 Christian prisoners in Silves at the start of the siege, only about 200 were still alive at the end.

After the Battle

Taking Control and Sharing Spoils

After Silves fell, nine other castles that had been controlled by Silves came under Portuguese rule. These included Lagos, Alvor, Portimão, Monchique, Santo Estêvão, Carvoeiro, São Bartolomeu de Messines, Paderne, and Carphanabel (which is not clearly identified today). Most of these places were empty because their people had fled to Silves. The governor of Albufeira surrendered to the Portuguese because he feared the crusaders.

The crusaders first occupied Silves to divide the valuable items. The original agreement with King Sancho said they could keep everything, but during the siege, they agreed to give some to the king for his army. Sancho claimed the city's grain stores. The division of valuable items became chaotic. To avoid more trouble, the crusader leaders gave the city to King Sancho. They asked him to give them a fair share of what was left, but he did not.

King Sancho had also promised to give a tenth of the conquered lands to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as payment for delaying the crusaders, but he later broke this promise. He stayed in Silves until September 12, setting up a military group and appointing his lieutenant as governor. This new governor appointed a Fleming named Nicholas as the new bishop of Silves. As a result, some Flemish crusaders chose to stay in Silves. Nicholas dedicated the mosque as a cathedral on September 8. He also asked the departing crusaders to help the Portuguese attack Faro, but they refused.

Crusade Continues

The crusader fleet sailed on September 7 but stopped to divide valuable items and repair two ships. They did not enter the Atlantic Ocean until September 20. They passed Saltes Island, whose people fled when they approached. Strong winds forced them to enter the port of Cádiz on September 26. People from Silves had warned the residents, and most had fled. The governor of Cádiz agreed to release twelve Christian prisoners and pay a tribute. However, only four prisoners were handed over, so the crusaders went on a rampage, burning houses and destroying vineyards.

The crusaders sailed from Cádiz on September 28 and landed at Tarifa on September 29. They then sailed through the Strait of Gibraltar on the night of September 29-30. In the Mediterranean Sea, the fleet followed the European coast. The historical account ends with the fleet in Montpellier and Marseille. They might have spent the winter in Marseille or Sicily.

The crusader fleet from Silves likely arrived at Acre in the Middle East between April and June 1190. Merchants and commoners from Bremen and Lübeck who arrived on large ships were part of this fleet. They used wood and cloth from their ships to build a field hospital. This hospital eventually grew into the Teutonic Order, a famous military and religious order.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |