Siege of St. Augustine (1702) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of St. Augustine |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Queen Anne's War | |||||||

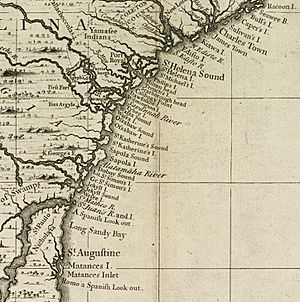

A 1733 map showing the coast between Charles Town and St. Augustine. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| José de Zúñiga y la Cerda Estevan de Berroa Captain López de Solloso |

James Moore | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 204 regulars and marines 1,500 civilians |

500–600 provincial militia 300–600 Indians |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| reports vary; light | reports vary; light | ||||||

The Siege of St. Augustine happened in November and December of 1702. This event was part of a bigger conflict called Queen Anne's War. English colonists from the Province of Carolina and their Native American allies attacked the Spanish fort of Castillo de San Marcos. This fort was located in St. Augustine, which was then part of Spanish Florida.

The English forces were led by Governor James Moore of Carolina. They arrived at St. Augustine on November 10, 1702. The Spanish governor, José de Zúñiga y la Cerda, knew they were coming. He quickly moved all the town's people and food supplies inside the strong fort. He also sent messages asking for help from other Spanish and French areas.

The English cannons did not do much damage to the fort's thick walls. Governor Moore asked for bigger guns from Jamaica. Meanwhile, the Spanish calls for help worked. A fleet of ships from Havana, Cuba arrived with troops on December 29. Moore decided to end the siege the very next day. He had to burn many of his own boats before retreating back to Charles Town.

Contents

Why the Siege Happened

English and Spanish settlers in North America often had conflicts. This started in the mid-1600s. When the English founded the Province of Carolina in 1663 and Charles Town in 1670, tensions grew. Spanish Florida was already settled by Spain. Traders and slave hunters from Carolina often went into Spanish Florida. This led to attacks and counter-attacks from both sides.

In 1700, Carolina's governor, Joseph Blake, threatened the Spanish. He said the English would claim Pensacola, which Spain had built in 1698. Blake died later that year. James Moore became the new governor in 1702.

Even before news of a major war arrived, Moore wanted to attack St. Augustine. This war was called the War of the Spanish Succession in Europe, but in North America, it was known as Queen Anne's War. When news of the war reached the colonies in 1702, Moore convinced the Carolina assembly to pay for an attack on St. Augustine.

Moore gathered a fighting force. It included colonists and Native American warriors. These warriors were mainly from the Yamasee, Tallapoosa, and Alabama tribes. A Yamasee chief named Arratommakaw led them. The total number of fighters varied, but most sources say about 500 colonists and 300–400 Native Americans took part.

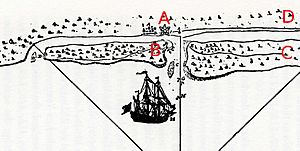

Some of these forces, mostly the Native Americans, traveled by land. They went to Port Royal. Governor Moore sailed with the rest of the force on 14 boats. They all met at Port Royal. Then, Moore's forces landed on what is now Amelia Island. Moore then sailed on to Matanzas Bay.

The Castillo de San Marcos fort in St. Augustine was built in the late 1600s. Earlier English raids showed that wooden forts were not strong enough. This new fort was made of soft coquina limestone. It was a strong, star-shaped fort. Governor Joseph de Zúñiga y Zérda took command of the fort in 1700.

Native Americans friendly to the Spanish heard about the English plans. News reached Zúñiga on October 27. He ordered everyone in the town to go inside the fort. He also collected all the food, expecting a long siege. He sent messages to Pensacola, Havana, and the French at Mobile asking for help. About 1,500 civilians, including many refugees, crowded into the fort. Zúñiga thought they had enough food for three months.

Some of Zúñiga's men wanted to fight the English outside the fort. But Zúñiga decided to prepare for a siege. He had 174 regular soldiers and 14 artillerymen. He also had 44 Europeans, 123 Native Americans, and 57 black men (freemen, mulattoes, and slaves). Many of these men were not well-trained or well-armed. Zúñiga felt only about 70 men were truly ready for battle. His main worry was his artillerymen, who were not very experienced.

The Battle Begins

English Advance

Deputy Governor Daniell's forces landed on Amelia Island. They attacked the northern part of the island on November 3. They killed two Spanish soldiers and took over the village of San Pedro de Tupiqui. They moved south, pushing Spanish troops and refugees ahead of them. The main Spanish settlements at San Felipe and San Marcos were taken the next day. The Spanish were already leaving these places.

Zúñiga learned of the English advance on November 5. He sent 20 men north to San Juan del Puerto. This place was important for defending the area. The news also made Zúñiga order all men over 14 to prepare for battle. He also ordered all available food into the fort.

Captain Horruytiner, leading the Spanish men, did not get past the St. Johns River. On November 6, he captured three enemy soldiers. These were two Englishmen and a Native American. He returned to St. Augustine two days later. Zúñiga learned from these captives that the English had three months of supplies. He also found out they only had smaller cannons.

Meanwhile, Governor Moore sailed south with his fleet. Three ships went ahead to block the entrance to Matanzas Bay. This bay was south of St. Augustine. The fort spotted these ships on November 7. The next day, the main fleet started arriving outside the St. Augustine inlet. Zúñiga ordered his two Spanish ships to anchor under the fort's guns. One ship could not cross the sandbar and was burned. Sixteen of its men joined the fort's defenders, bringing useful gunnery skills.

Daniell's land force moved quickly. The small Spanish force on Amelia Island could not stop the English. They were scattered. Daniell continued to advance and entered the town of St. Augustine without a fight on November 10. Eight English ships crossed the sandbar and began landing men that day. As the English surrounded the fort, a Spanish group managed to bring 163 cattle through the English lines. The cattle went into the fort's dry moat.

The Siege Begins

The Spanish guns started firing at the English on November 10. This was when the English began setting up their siege. One old Spanish cannon exploded that day. It killed three men and wounded five. A few days later, Zúñiga ordered a small attack. This attack destroyed parts of the town that were close to the fort. This action destroyed property worth more than 15,000 pesos.

Moore had brought four small cannons. But these guns did little damage to the fort's coquina walls. The Spanish guns had a longer range. This kept most of Moore's forces far away. Around November 22, Moore sent Deputy Governor Daniell to Jamaica. He went to get bigger cannons and more ammunition. The English kept digging siege trenches. They started firing at the fort from musket range on November 24. This cannon fire still had little effect. Moore ordered more of the town burned the next day, including the Franciscan monastery.

Since his cannons were not working, Moore tried a trick to get into the fort. On December 14, a Yamasee couple got into the fort. They pretended to be refugees. Their goal was to blow up the fort's powder storage. But Zúñiga was suspicious of them. According to his report, they were tortured and admitted their plan.

By December 19, the English trenches were very close to the fort. They were threatening nearby fields where the Spanish collected food. So, Zúñiga ordered another small attack. There was a skirmish. Spanish casualties were light: one killed and several wounded.

Help Arrives

Spanish leaders at Mission San Luis de Apalachee (now Tallahassee, Florida) started to prepare when they heard about the siege. They needed supplies. They asked the French at Mobile for help. The French gave them important guns and gunpowder. The Pensacola soldiers also sent ten men. This relief force left San Luis de Apalachee on December 24. But they turned back when they heard the siege had ended.

Also on December 24, two ships were seen approaching St. Augustine. English records do not say what these ships were. Spanish records show they were English, but probably not from Jamaica. The siege did not change when they arrived. The expedition to Jamaica failed to get bigger cannons. It returned directly to Charles Town.

Spanish messengers from Pensacola finally told Havana about St. Augustine's trouble. Governor Pedro Nicolás Benítez held a meeting on December 2. They decided to send a relief expedition. Over 200 soldiers, led by Captain López de Solloso, sailed on a small fleet. General Estevan de Berroa led this fleet in his ship, the Black Eagle. Berroa's fleet arrived outside St. Augustine's harbor on December 28.

Berroa seemed to think the siege was already over. He did not land any troops. The next day, Governor Zúñiga secretly sent some men out of the fort. They made contact with the fleet. Berroa then landed Solloso and about 70 new soldiers on Anastasia Island. This island was about 3 miles (4.8 km) from the fort. This action made Moore decide to end the siege and prepare to retreat. Berroa also sent smaller ships to block the southern entrance to Matanzas Bay. This trapped some of Moore's ships in the bay.

Moore ordered the remaining buildings in the town, including the church, to be burned. Some of his men left by land to the north. The rest crossed Matanzas Bay to their boats. Moore burned the eight ships trapped in the bay. He then retreated north, eventually returning to Charles Town. He was seen as a failure. Zúñiga sent men out after the English left. They were able to get back three English boats that did not burn completely.

Reports of casualties (deaths and injuries) from both sides were different. Historians say that all the numbers might not be correct. Moore's report said only two of his men were killed. Zúñiga claimed that more than 60 English soldiers were killed. Zúñiga said only three or four Spanish soldiers were killed and 20 wounded. None of these were from English cannon fire.

What Happened Next

Moore had to leave his job as governor because the raid failed. The cost of the raid caused problems in Charles Town. This included paying owners for their lost ships. Some people at the time said Moore only attacked to get slaves or treasure. The Spanish saw it as an attack on their religion. Moore continued to fight in the war. He led a group of Carolinians and many Native Americans to destroy Spanish missions in Florida in 1704. By August 1706, the Carolinians had destroyed almost everything in Spanish Florida. St. Augustine became the only Spanish settlement left in Florida.

Governor Zúñiga was rewarded for his successful defense. He received a special praise from the king. He was also promoted to a better governorship in Cartagena. He complained a lot about General Berroa. Zúñiga said the general failed to destroy the English fleet. He also said Berroa did not share the treasure taken from the burned ships. Berroa also refused to leave any of his fleet to protect the town. He only landed the weakest troops to avoid fighting. The general sailed for Havana on January 8, just one week after the siege ended.

In 1704, Governor Zúñiga convinced some Spanish privateers (private ships allowed to attack enemy ships) to raid the Carolina coast. This was revenge for Moore's actions. Spanish and French forces tried to capture Charles Town in August 1706. Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville helped plan this attack. But their attempts to land troops were stopped.

The Castillo de San Marcos was not attacked again during this war. The expedition destroyed all but two communities in the Spanish provinces of Guale and Timucua. Spanish Florida never fully recovered from the loss of its people in the years that followed. St. Augustine was again attacked unsuccessfully in 1740. This attack was by forces from the Province of Georgia. The fort was changed and used many times in the 1700s and 1800s. Today, it is a National Monument. It is managed by the National Park Service and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Sitio de San Agustín (1702) para niños

In Spanish: Sitio de San Agustín (1702) para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |