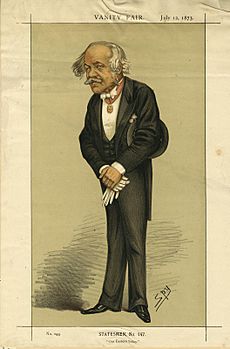

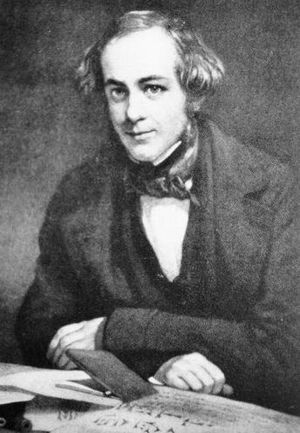

Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Rawlinson

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| President of the Royal Geographical Society | |

| In office 1871–1873; 1874–1876 |

|

| Preceded by | Sir Roderick Murchison |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Frere |

| Member of Parliament for Frome | |

| In office 1865–1868 |

|

| Preceded by | Lord Edward Thynne |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Hughes |

| Member of Parliament for Reigate | |

| In office February – October 1858 |

|

| Preceded by | William Hackblock |

| Succeeded by | William Monson |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Henry Creswicke Rawlinson

5 April 1810 Chadlington, England |

| Died | 5 March 1895 (aged 84) London, Middlesex, England |

| Resting place | Brookwood Cemetery, Surrey |

| Political party | Liberal Party |

| Relatives | George Rawlinson (brother) |

| Employer | British East India Company |

| Awards |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | British Army |

| Rank | Major-general |

| Wars | First Anglo-Afghan War |

Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (born April 5, 1810 – died March 5, 1895) was a British army officer, politician, and expert in ancient Eastern cultures. He is often called the "Father of Assyriology" because of his amazing work. Assyriology is the study of the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, like Assyria and Babylonia. His son, also named Henry, became a famous general in the British Army during World War I.

Contents

Early Life and Army Service

Henry Rawlinson was born in Chadlington, England, in 1810. He was the second son in his family. In 1827, when he was 17, he joined the British East India Company's army. He was very good at learning languages. He quickly became skilled in Persian. Because of this, he was sent to Iran (then called Persia). His job was to help train and organize the Shah's (king's) soldiers.

However, there were disagreements between the Persian government and the British. These problems also involved Russia, as part of a rivalry known as the "Great Game" in Asia. Because of these issues, the British officers, including Rawlinson, had to leave Persia.

Deciphering Ancient Scripts

After leaving the army, Rawlinson started to study ancient Persian writings. He was especially interested in cuneiform, a wedge-shaped writing system. Other scholars had only partly figured out this script. From 1836, he spent two years in Kermanshah, Iran. This area was close to the famous Behistun Inscription. This huge inscription was carved into a cliff by Darius the Great around 522 to 486 BC. It was written in three ancient languages: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian.

Rawlinson bravely climbed up a shaky ladder to reach the inscription. He was the first Westerner to copy the Old Persian part of the text. Using his knowledge of Old Persian, he then worked on figuring out the Elamite and Babylonian sections. This was a huge step in understanding these ancient languages.

Political Career and Discoveries

In 1840, Rawlinson became a political agent in Kandahar, Afghanistan. He served there for three years. In 1844, he was honored for his service to the British Empire during the First Anglo-Afghan War.

Later, he was appointed as a political agent in Ottoman Arabia. He settled in Baghdad, a city in modern-day Iraq. There, he focused even more on his cuneiform studies. By 1847, he successfully sent a complete and accurate copy of the Behistun inscription to Europe. He also managed to fully decipher and explain its meaning.

Rawlinson gathered a lot of information about ancient sites and geography. He even visited the ruins of Nineveh with another famous archaeologist, Sir Austen Henry Layard. In 1849, he returned to England for a break.

Recognized for His Work

In 1850, he became a member of the Fellow of the Royal Society. This was a great honor. They praised him as "The Discoverer of the key to the Ancient Persian, Babylonian, and Assyrian Inscriptions."

He stayed in England for two years. In 1851, he published his detailed report on the Behistun inscription. The British Museum bought his valuable collection of ancient artifacts from Babylon, Sabaea, and the Sassanian Empire. They also gave him money to continue the excavations started by Layard in Assyria and Babylonia.

In 1851, he went back to Baghdad. His new archaeological finds greatly helped in finally deciphering and understanding the cuneiform writing system. Rawlinson's most important discovery was realizing that a single cuneiform sign could have different meanings depending on how it was used. He worked with a younger scholar named George Smith at the British Museum.

In 1855, an accident while riding a horse made him decide to return to England for good. He resigned from the East India Company. Before leaving, he was involved in a sad event where over 200 cases of ancient artifacts being shipped to Europe were mostly lost in a disaster at Al-Qurnah.

Back in England, he received another honor, becoming a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath. He was also made a director of the British East India Company.

Life in London

For the next forty years, Rawlinson was very active in politics, diplomacy, and science, mostly in London. From February to September 1858, he was a Member of Parliament for Reigate. He also joined the first India Council, which advised the British government on India.

In 1859, he was sent to Persia again as a special ambassador. However, he was not happy with the job and returned after a year. He was a Member of Parliament for Frome from 1865 to 1868. He continued to serve on the Council of India from 1868 until his death.

Views on Russia

Rawlinson was a key figure who believed Britain needed to stop Russia from expanding its power in South Asia. This was part of the "Great Game" rivalry. He strongly supported a "Forward Policy" in Afghanistan. This policy meant Britain should be more active in Afghanistan to protect its interests. He thought Britain should keep control of Kandahar.

He warned that Russia would take over areas like Khokand, Bokhara, and Khiva (which are now parts of Uzbekistan). He also predicted that Russia would try to invade Persia (Iran) and Afghanistan. He believed these invasions would be a way for Russia to get closer to British India.

Later Life and Legacy

From 1876 until his death, Rawlinson was a trustee of the British Museum. He received more honors, becoming a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1889 and a Baronet in 1891. He was president of the Royal Geographical Society from 1874 to 1875. He also led the Royal Asiatic Society for several years. He received special degrees from famous universities like Oxford, Cambridge, and Edinburgh.

He married Louisa Caroline Harcourt Seymour in 1862. They had two sons, Henry and Alfred. His wife passed away in 1889. Henry Rawlinson himself died in London from the flu five years later. He is buried in Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey.

Published Works

Rawlinson wrote many important books and articles. These include four volumes of cuneiform inscriptions. The British Museum published these under his guidance between 1870 and 1884. He also wrote The Persian Cuneiform Inscription at Behistun (1846–1851). Another work was Outline of the History of Assyria (1852). These were reprinted from the journals of the Asiatic Society.

Other notable works include A Commentary on the Cuneiform Inscriptions of Babylon and Assyria (1850). He also wrote Notes on the Early History of Babylonia (1854). His book England and Russia in the East (1875) discussed his views on the "Great Game." He contributed many smaller articles to scientific societies. He wrote about places like Baghdad and Kurdistan for the ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. He also helped edit a translation of The Histories by Herodotus, which was done by his brother, George Rawlinson.

See also

In Spanish: Henry Rawlinson para niños

In Spanish: Henry Rawlinson para niños